Alexander Miguel Roberts (October 13, 1895–July 23, 1988

Alexander Zimmerman

Early Life

Alexander Miguel Roberts was born on October 13, 1895 in Mexico City, Mexico, to Hiram Talliaferro (H.T.) Roberts, an American citizen, and Concepcion Galves. After baptizing their son Alefandro Miguyel Roberto Roberts Galves on November 27, 1895 at the Asunción Sagrario Metropolitano (Centro) Cathedral,1 the family moved back to the US and Concepcion became a naturalized American citizen.2 Roberts grew up in both Gulfport, Mississippi, and Havana, Cuba, as the Roberts family frequently traveled between the two cities. His connection with Mississippi was strong; he attended the Agricultural and Mechanical College of the State of Mississippi, now known as Mississippi State University.3 We can see a picture of him in his yearbook, The Reveille.

World War I Service

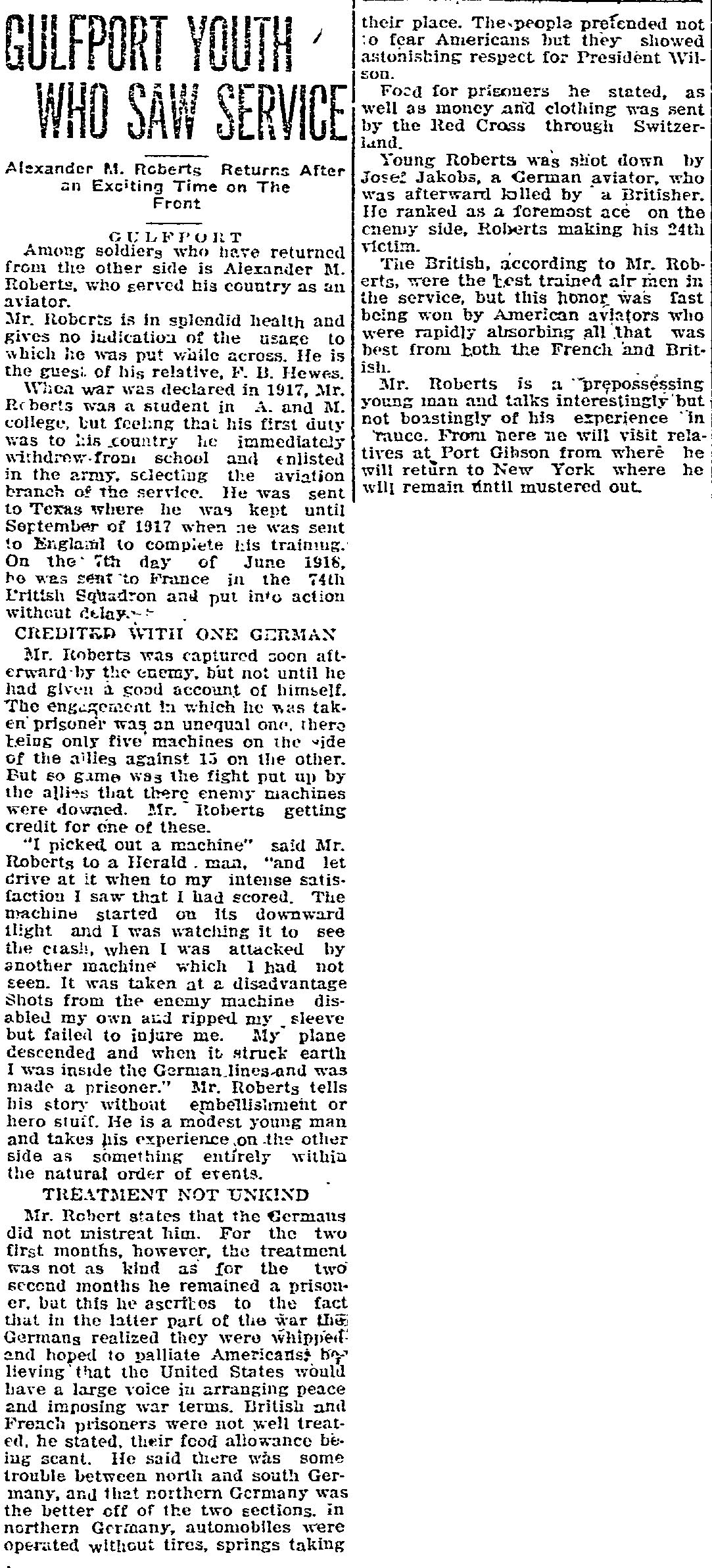

Just after the US entered the Great War on April 6, 1917, Roberts enlisted in the aviation branch of the Army at the age of twenty-one.4 Roberts became a celebrity during and after the war with his name splashed on dozens of newspaper headlines across the country. One article described Roberts’ decision to enter the service: “When war was declared in 1917, Mr. Roberts was a student… but feeling that his first duty was to his country he immediately withdrew from school and enlisted in the army, selecting the aviation branch of the service.”5 After his enlistment, Roberts began flight training in Texas before embarking to England in September of 1917 to finish flight school.6 Just a year after entering the service, Roberts earned his wings and went to France.

On July 19, 1918, German Ace Josef Jakobs shot down Roberts’ plane over Belgium on his first mission.7 At home the newspapers headlines blazed: “Gulfport Youth in German Prison,” and “A.M. Roberts Alive Though Prisoner, Young Aviator, Well-Known in Gulfport, Missing—Found in German Prison.”8 Syndicated articles appeared in newspapers across the country—everywhere from Biloxi, Denver, Chicago, and beyond.9 In his encounter with the Germans, Roberts managed to bring down one of the enemy planes despite his squad being outnumbered three to one.10 Roberts described his only combat mission this way:

I picked out a machine... and let drive at it when to my intense satisfaction, I saw that I had scored. The machine started on its downward flight and I was watching it to see the crash, when I was attacked by another machine which I had not seen. I was taken at a disadvantage. Shots from the enemy machine disabled my own and ripped my sleeve but failed to injure me. My plane descended and when it struck earth I was inside the German lines and was made a prisoner.11

After his capture, Roberts refused to stand down and attempted escape several times. Traveling from Liege, Belgium to Aachen, Germany, Roberts jumped out of the train he was traveling in and tried to make it to the border before being recaptured.12 On another occasion, he and fellow serviceman Hector Gray created a rope out of sheets to escape out of a window at the prison and then hid in the Black Forest for a week before returning to the prison for lack of food.13

Jakobs, the famous German aviator who had shot down twenty-three planes before his encounter with Roberts, visited Roberts in the prison camp. According to newspaper accounts, Jakobs expressed relief that Lt. Roberts was not hurt and let Roberts know that the pilot he shot down survived the crash as well.14 The German pilot promised to write to Roberts’ father.15 We can see Roberts’ personal account of his imprisonment in this article published in the Gulfport Daily Herald. Another article reported that, before learning that he had survived the crash, his parents “were full of anxiety and feared the worst.”16 The Germans eventually released Roberts in 1919.17

Interwar and World War II Eras

.Within a few years of returning to civilian life in April of 1923, Roberts married Mary Adolfina Gutierrez y Sanchez in Havana, Cuba.18 He also continued his career as a pilot, appearing in air shows and in a cross-country air race with both events covered by syndicated newspaper articles across the country.19 In one case, he had to ditch his plane in Lake Erie during a race.20 The new international sport of air racing became a top radio and newspaper story from coast-to-coast. The outcome of the Cloud Derby, the cross-country race, was hotly contested and the media coverage made Alexander M. Roberts well-known nationwide. He used his fame to promote the aviation industry and the new ‘Aerial Age.’ He urged his hometown and other communities in Mississippi to build more airfields and contended that aviation would provide economic benefits including new jobs.21

For most of his life, Roberts continued to travel to and from Havana, Cuba. He grew up in a family that had business dealings in both Mississippi and Havana, and his sister married someone in Havana’s manufacturing industry. 22 Sometime before 1941, Roberts separated from his first wife and married Estela S. Roberts.23 In 1942, when Roberts registered for the World War II draft, he lived in Havana, Cuba with his wife Estela and worked for the family business, Roberts & Company.24 Promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, Roberts served as an official aide and an aviation advisor to the US Army during World War II. Among his many duties, Roberts escorted General Oscar Torres, Peruvian Minister of War, and his family on a flight into Washington, DC, in 1945.25

Lieutenant Colonel Roberts excelled in his service to our country in both world wars. He helped generate enthusiasm for the birth of aviation in America. He was a son, husband, and father. Alexander Miguel Roberts was a community leader and businessman. His story does not end in 1945 or with his last recorded trip from Cuba in March of 1959, the same year as the Communist Revolution. Yet, the family business likely changed dramatically after 1959, when it would have lost all its holdings and trade with Cuba. While it is not clear when Roberts moved to Florida, he died at 92 years of age on July 23, 1988 in Tampa. He is buried in the Florida National Cemetery in Bushnell, Florida.26

Endnotes

1 “Mexico, Distrito Federal, Catholic Church Records, 1514-1970,” database, Familysearch.org, https://Familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:N194-9MZ (accessed March 27, 2017), entry for Alefandro Miguyel Roberto Roberts Galves, GS Film Number 35220.

2 “U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925,” database, Ancestry.com, https://Ancestry.com (accessed March 28, 2017), entry for Mrs Concepcion Galvez Roberts, Certificate Number 64062.

3 “Gulfport Youth Who Saw Service: Alexander M. Roberts Returns After an Exciting Time on The Front,” Gulfport Daily Herald (Gulfport, Mississippi), February 19, 1919.

4 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com, https://Ancestry.com (accessed March 28, 2017), entry for Alexander Miguel Roberts, Number 486.

5 “Gulfport Youth Who Saw Service,” Gulfport Daily Herald.

6 Ibid.

7 “Roberts Thinks He Got 1 Machine,” Gulfport Daily Herald (Gulfport, Mississippi), October 11, 1918.

8 “Gulfport Youth in German Prison,” Gulfport Daily Herald (Gulfport, Mississippi), August 20, 1918.; “A.M. Roberts Alive Though Prisoner: Young Aviator, Well-Known in Gulfport, Missing – Found in German Prison,” Daily Herald, (Biloxi, Mississippi), August 31, 1918.

9 “Prisoner, Not Previously Reported Missing,” Denver Rocky Mountain News, (Denver, Colorado), September 5, 1918.; “Prisoner, Not Previously Reported Missing – Lieutenant,” Daily Illinois, (Chicago, Illinois), September 5, 1918.

10 “Gulfport Youth Who Saw Service,” Gulfport Daily Herald.

11 Ibid.

12 Edgar S. Gorrell, Gorrell's History of the American Expeditionary Forces Air Service, 1917-1919

(WAshington DC: National Archives and Records Service, General Services Administration, 1975).

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 “A.M. Roberts Alive Though Prisoner,” Daily Herald.

17 “Gulfport Youth Who Saw Service”, Gulfport Daily Herald.

18 “U.S., Consular Report of Marriages, 1910-1949,” database, Ancestry.com, http://Ancestry.com (accessed July 6, 2017), entry for Alexander Miguel Roberts and Mary Adolfina Gutierrez y Sanchez, File Number 133.

19 “Here Is List of Fliers in Cloud Derby,” Salt Lake Telegram, (Salt Lake City, Utah), October 8, 1919.

20 “Gulfport Fliers Fall in Lake Erie,” Gulfport Daily Herald (Gulfport, Mississippi), October 9, 1919.

21 “Importance of Flying Fields,” Daily Herald (Biloxi, Mississippi),June 19, 1919.

22 “Osorio-Roberts”, Daily Herald (Biloxi, Mississippi), September 3, 1917.

23 “Florida, Passenger Lists, 1898 - 1963,” database, Ancestry.com, http://www.ancestry.com (accessed August 24, 2017), entry for Estela S Roberts, Arrival: Miami, Florida; “Index to Alien Arrivals by Airplane at Miami, Florida, 1930 - 1942,” database, Ancestry.com, http://www.ancestry.com (accessed August 24, 2017), entry for Estela S Roberts, September 25, 1941, Arrival: Miami, Florida.

24 “U.S. World War II Draft Registration Cards,” database, Ancestry.com, https://ancestry.com (accessed March 28, 2017) entry for Alexander Miguel Roberts, Serial Number 147.

25 “World War II War Diaries, 1941-1945,” database, Fold3.com, https://fold3.com (accessed March 28, 2017), entry for Com 7, 8/1-31/45, micro serial number 145317, page 38.

26 National Cemetery Administration, "Alexander Miguel Roberts," US Department of Veterans Affairs, accessed September 18, 2018, https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/NGLMap?ID=3317450

© 2017, University of Central Florida