Archie Hawkins (February 12, 1902–February 27, 1989)

By Harper Norris

Early Life: Growing up in Florida

Archie Hawkins was born to Doc and Lilly Hawkins in Lloyd, a city in the Florida Panhandle on February 12, 1902. Doc Hawkins worked as a laborer for most of Archie’s life, and lived in relatively poor conditions. According to the 1910 census, as a young boy Archie was illiterate, and worked as a farm laborer in Lloyd, Florida. 1 Sometime between 1910 and 1917, Archie moved to Greenville, Florida, where he attempted to register for the draft in Madison County in June of 1917.

Military Service: Entering World War I

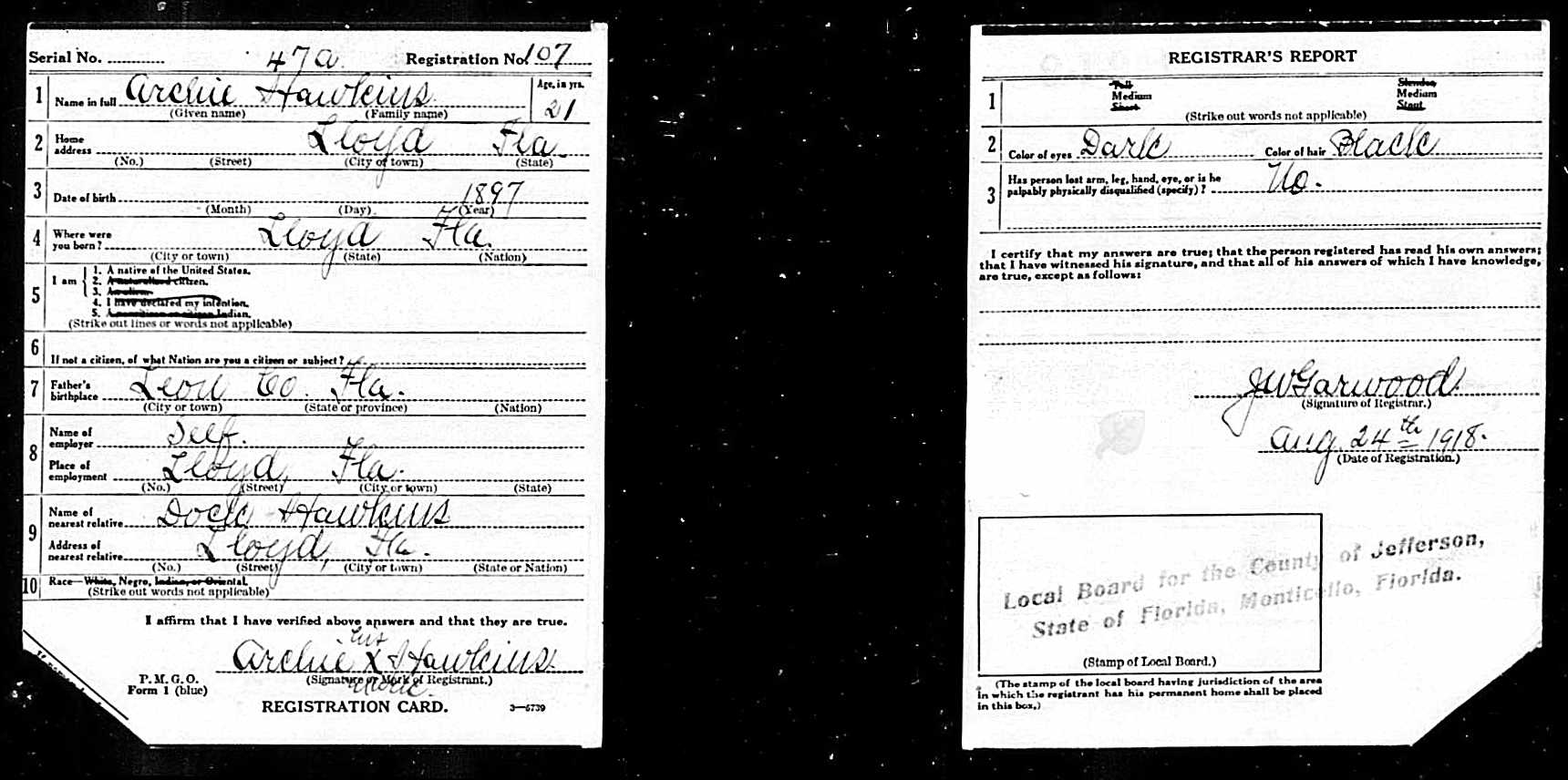

On the draft registration card for 1917, shown here, Archie listed his date of birth as 1896, making him exactly twenty-one, the required age for draft registration. 2 Whether the incorrect age was a product of administrative error or Archie lying about his age to enlist is difficult to tell, but falsifying a birthday to enlist in World War I was not an uncommon practice. 3 One year later, in 1918, the Hawkins family moved back to Lloyd where Archie registered for the draft a second time on August 24, 1918. This time Archie’s birth date was listed as 1897, again making him twenty-one and eligible for the draft. The second time the Army did not turn him away. 4

Archie was drafted and mustered in on September 26, 1918. His service card includes misinformation. According to the card, Archie mustered in at Monticello, Alabama; however his draft records indicate that he registered for the draft in Monticello, Florida. 5 It is likely that Archie was inducted at Monticello, Florida, and not in Alabama. 6 The birthday listed on his service card is also inaccurate, likely because he entered the service prior to his twenty-first birthday.

Archie joined the Army along with approximately two hundred other black men from Jefferson County. According to scholars, many African Americans were eager to fight in hopes that serving their country would make it impossible for white Americans to continue to deny black veterans rights and liberties. 7 Nonetheless, African Americans served in segregated units during World War I, frequently in domestic support units. 8 Archie was assigned to the Auxiliary Remount Depot number 333, a segregated unit stationed at Camp Joseph E. Johnston in Jacksonville, Florida. 9 The unit, a cavalry regiment, is pictured here. Although the unit never saw any action overseas, its men faced dangers including disease and workplace hazards in the camp. The Division commander, prompted by problems of illness and other health risks, requested that his regiment be provided with the same war-risk insurance as the rest of the army. 10 In 1918, as many of the army’s horse cavalry divisions were being phased out, it is likely that Archie’s division remained active in order to test the use of “Sal-Tonik” as a salt replacement and medical treatment for their horses. The division commander reported that the innovation made the horses healthier and stronger. 11

Post-Military Life: Returning Home

Archie was discharged on December 14, 1918, after serving almost three months. 12 Archie returned to Jefferson County where he, along with other black veterans, were treated with hostility. During the summer after World War I, known as the Red Summer, African Americans faced intense, widespread racial violence and discrimination throughout the US. 13 One incident that exemplifies the racial tensions of the time was the “Welcome Home” reception held on September 25, 1919 in Charles Town, West Virginia. Even though the newspaper advertised the event as “free to all men in uniform,” African American veterans were excluded. 14 African American veterans faced discrimination when they enlisted, when they served, and when they returned home. 15 As of 1920, Archie was unemployed, living with his two brothers, Ray and James Hawkins, and Ray’s wife Moody. Archie had gained the ability to read and write, possibly through his time in the army, despite never attending formal school. 16

Archie remained in Lloyd, Florida, until he moved to St. Petersburg in 1929, where he worked as a landscape gardener until he retired. He had a daughter named Doris Washington who fostered eight children, ten grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Archie died on February 27, 1989 in Pinellas County, Florida. 17

The records of Archie’s life have multiple errors and highlight a lack of attention and appreciation given to African Americans by the U.S. government at the federal, state, and local level in the early twentieth century. Although forgotten throughout his life, today, Archie is remembered in the Florida National Cemetery. He is buried in plot 103, 975 and his headstone and obituary indicate that he was a Baptist at the time of his death. 18

Endnotes

1 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com, (www.ancestry.com accessed March 17, 2017), entry for Archie Hawkins, Lloyd, Jefferson, Florida.

2 “World War 1 Draft Registration Cards 1917-1918”, database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com accessed March 17, 2017) entry for Archie Hawkins, Roll: 1556867.

3 Gerald E. Shenk, “Work or Fight!”: Race, Gender, and the Drat in World War I (New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2005), 135.

4 “World War 1 Draft Registration Cards 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com accessed March 17, 2017) entry for Archie Hawkins, Lloyd, Jefferson, Florida, 1917.

5 “United States World War One Army Service Cards,” database, Floridamemory.org, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/224950 (accessed March 10, 2017), entry for Archie Hawkins, Army Service number 2910439.

6 “World War 1 Draft Registration Cards 1917-1918, ”database, Ancestry.com, www.ancestry.com (accessed March 17, 2017) entry for Archie Hawkins.

7 Chad L. Williams, Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era ( Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 69; Mary Stortstrom “Fighting for Dignity: Black WW1 Soldiers from Jefferson County fought in, returned to unjust conditions,” The Journal (February 12, 2017): http://www.journal-news.net/news/local-news/2017/02/fighting-for-dignity-black-wwi-soldiers-from-jefferson-county-fought-in-returned-to-unjust-conditions

8 Jami Bryan “Fighting for Respect: African American soldiers in World War One,” Military History Online, accessed March 18, 2017, MilitaryHistoryOnline.com.

9 “United States World War One Army Service Cards,” Floridamemory.org, entry for Archie Hawkins

10 Compilation of war risk insurance letters, treasury decisions, and war calculators (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1919), 98-99.

11 Annual Report of The Federal Trade Commission 1921 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1921), 128.

12 “United States World War One Army Service Cards”,Floridamemory.org, entry for Archie Hawkins.

13 Williams, Torchbearers of Democracy, 260;

Richard Slotkin, Lost Battalions: The Great War and the Crisis of American Nationalism (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2005), 213.

14 Mary Stortstrom, “Fighting for Dignity: Black WW1 Soldiers from Jefferson County fought in, returned to unjust conditions,” The Journal (Charles Town, Florida), February 12, 2017: http://www.journal-news.net/news/local-news/2017/02/fighting-for-dignity-black-wwi-soldiers-from-jefferson-county-fought-in-returned-to-unjust-conditions

15 Dr. John Morrow, “Only America Left Her Negro Troops Behind, The African American Military in the First World War” (paper presented at the University of Central Florida Pauley Lecture Series, Orlando, Florida, April 3, 2017).

16 “1920 United States Federal Census”, database, Ancestry.com, www.ancestry.com (accessed March 17, 2017), entry for Archie Hawkins, Lloyd, Jefferson, Florida.

17 “Florida Death Index 1934-2014”, database, Ancestry.com, www.ancestry.com (accessed March 17, 2017), entry for Archie Hawkins, Lloyd, Jefferson, Florida.

18 “Hawkins, Archie,” St. Petersburg Times (St. Petersburg, Florida), March 1, 1989;

National Cemetery Administration, "Archie Hawkins," US Department of Veterans Affairs, accessed March 17, 2017, https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/NGLMap?ID=3858200

© 2017, University of Central Florida