William Emanuel Kirlew (October 22, 1898–July 3, 1991)

By Matthew Shoaff

Early Life: Immigration and Education

On October 22, 1898, Emmanuel Kirlew and Margaret Morris gave birth to a son, William Emanuel Kirlew in Darliston, Jamaica. 1 The family later settled in the country’s capital of Kingston. At the age of fourteen, William immigrated to the United States, via Ellis Island, on board the ship Santa Maria, landing on April 12, 1912. 2 Kirlew’s migration coincided with the first wave of West Indian migrants to the US between the 1890s and 1920s. Jamaicans came seeking better employment opportunities. The tourism and banana industries between the US and the West Indies helped contribute to this wave of migration, including 13,000 West Indian migrants in 1911-1912 alone, making cities like New York centers for West Indian migration. 3 Kirlew eventually settled in New Britain, Connecticut. 4

While living in Connecticut, Kirlew gained the opportunity to receive an education at the Virginia Union University in Richmond, Virginia. The historic black university, formed through efforts by Northern Baptists in 1899, sought to give blacks, especially those in the South, more educational opportunities. The school served several functions, incorporating a theological school, a college, a manual training academy, a preparatory department and a girl’s college nearby. 5 During the 1917-1918 school year, the university listed Kirlew as a student in the Secondary Preparatory School as an eighth grade grammar student. 6

Service: Kirlew and African Americans During World War I

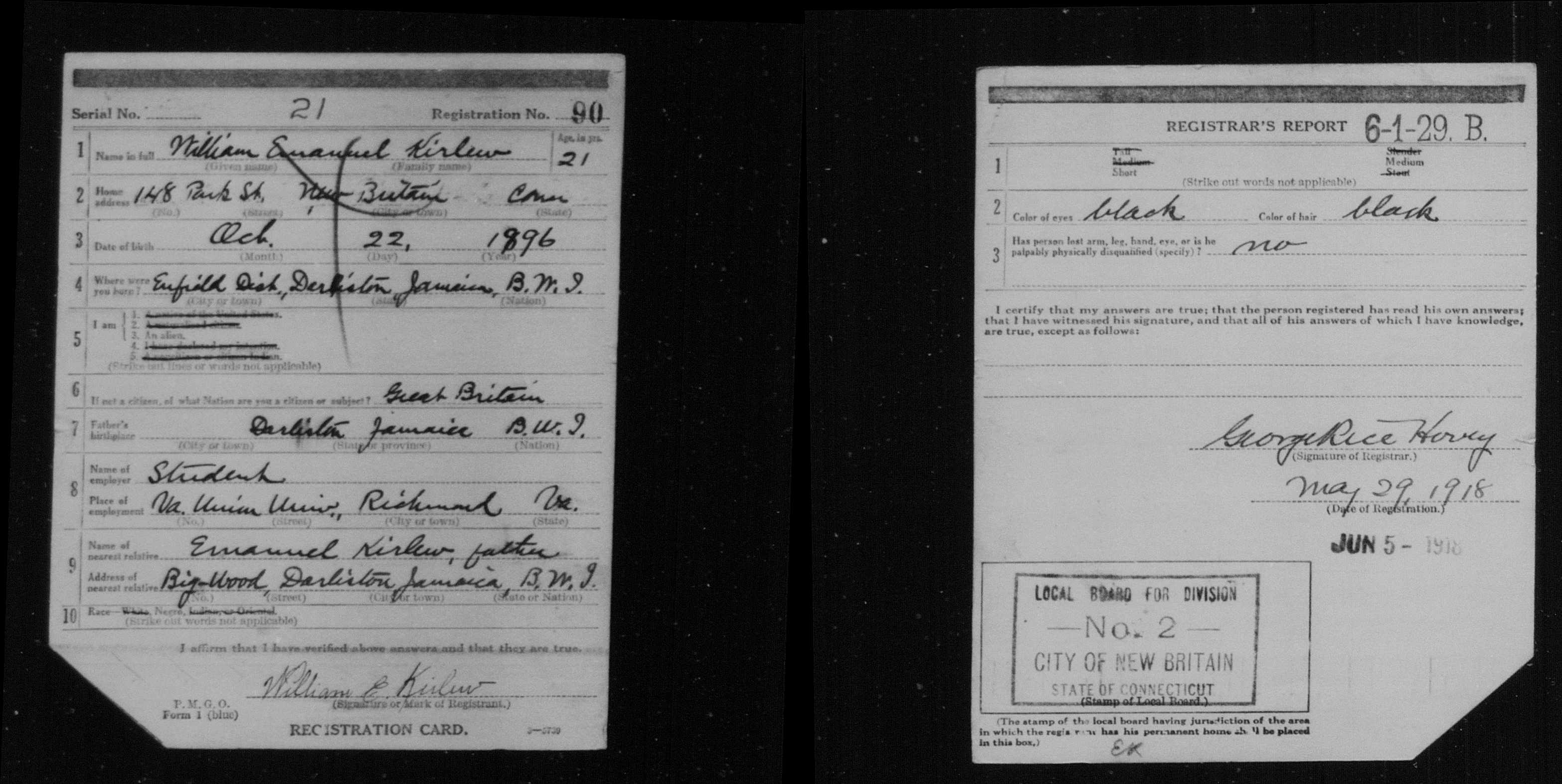

Though a British citizen when the United States entered World War I, Kirlew interrupted his studies and registered for the draft on May 29, 1918. Due to a 1917 draft law listing the minimum age of registration as age twenty-one, Kirlew added two years to his age, (as pictured here) listing his birth year in 1896. 7 Coming from Jamaica where blacks represented the majority of the population, many immigrants like Kirlew faced rude introductions to race in the United States. Feelings of “puzzlement, frustration, and anger” shaped the experiences of many of these immigrants. 8 Despite his West Indian origin, in the eyes of white Americans, Kirlew appeared as part of the black population. Kirlew joined the US Army in a time when African Americans sought political and civil rights. Leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois supported black participation in the war in hopes of delivering political and economic gains for African Americans. Harry C. Smith, editor of the black newspaper the Cleveland Gazette, argued the war could serve “to show the metal of which we African Americans are made.” 9

Kirlew found himself assigned to the 51st Depot Brigade beginning on September 1, 1918. 10 Depot Brigades essentially served the purpose of clothing, equipping, and training recruits for battle. 11 The Armed Forces practiced racial segregation during World War I, so black soldiers like Kirlew served in segregated, mostly support units. Because of white fears about arming blacks, only a few black units saw combat in Europe. Due to the timing of his enlistment and the context of racial fears about African American combat units, Kirlew most likely did not serve overseas. This does not diminish his service to this country and his service deserves celebration. Upon the conclusion of the war, the Army honorably discharged Kirlew on December 7, 1918. 12

Despite the hopes of blacks advocating for military service as a path to civil rights, veterans like Kirlew continued to face discrimination and disenfranchisement from mainstream Americans. The war did inspire, in part, the geographical shift associated with the Great Migration. For several decades in the early twentieth century, large portions of the black population moved away from the South and into Northern cities like New York in search of better employment opportunities and a better quality of life. 13

Postwar: Life in Harlem, Naturalization, and Later Years

At the end of the war, Kirlew return to New York where he settled in the black neighborhood of Harlem. Kirlew’s time in New York coincided with the timeframe of the Harlem Renaissance from 1919 to 1935. Black artists and writers symbolized the New Negro, empowered after the war, through various music, literature and artwork. Neighborhoods like Harlem developed as black Southerners and migrants from the Caribbean migrated to New York due to their exclusion from white neighborhoods. 14

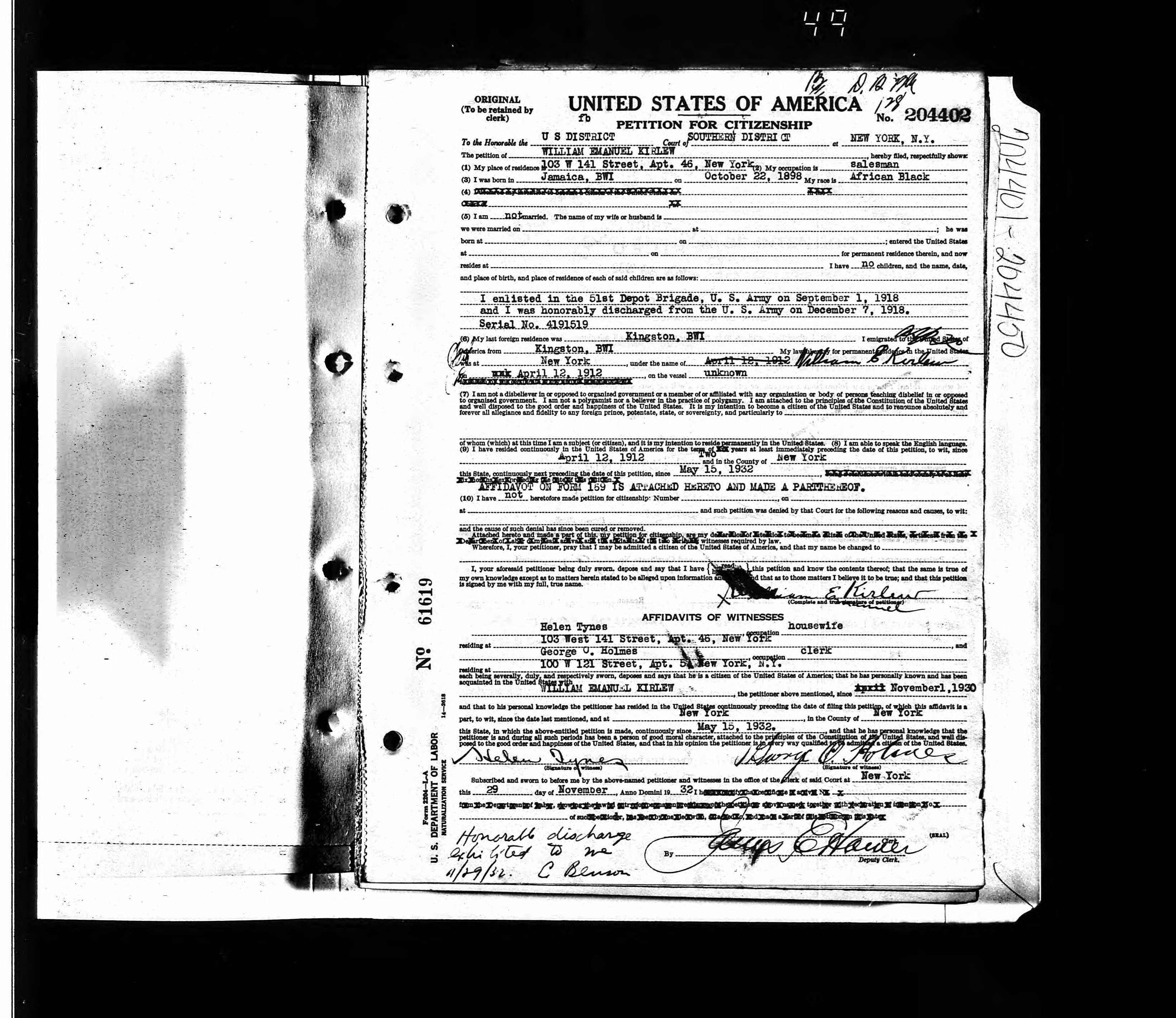

By the time of the Great Depression in the early 1930s, Kirlew boarded at the home of the Tynes family. The 1930 census reveals Harcourt Tynes, a fellow British West Indies native and local teacher, and his wife Helen, a housewife, owned an apartment in Harlem where they took in boarders. 15 In 1932, Kirlew filed paperwork, pictured here, to become a naturalized United States citizen and Helen served as Kirlew’s witness. 16 During the Great Depression, more immigrants sought citizenship, since the limited employment opportunities favored American citizens. In addition, many of the New Deal programs went only to citizens. 17 More opportunites and his veteran’s status must have served as the motivation for Kirlew to obtain his citizenship, which he gained on May 15, 1933 and where he listed his employment as a salesman. His petition for citizenship is pictured here. 18

As war broke out in Europe in 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt instituted the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 requiring all men between the ages of 21 and 35 to register at their local draft boards. After the US entered World War II in 1941, the age of enlistment broadened from twenty to forty five. 19 Yet, the government passed over many African American draftees in favor of white draftees and because of racial quotas within the armed services such as ten percent for the Army. 20 Kirlew, at the age of forty four, reenlisted in the Army on November 24, 1942. At the time of his second enlistment, Kirlew worked within the social and welfare occupation. 21 However, a few months later, on April 15, 1943, the Army discharged him. Age may have played a role in his short service. 22

Some time after the war, William Kirlew settled in South Florida where on July 3, 1991, he passed away at the age of 92. Kirlew is currently buried at the Florida National Cemetery located in Bushnell, Florida. 23 Kirlew’s legacy shows the willingness of a Caribbean immigrant to fight for this country despite facing the reality of racial discrimination in the US.

Endnotes

1 “U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007,” database, Ancestry.com, http://Ancestry.com (accessed June 8, 2017) entry for William E. Kirlew.

2 "New York Passenger Arrival Lists (Ellis Island), 1892-1924," database, FamilySearch.org, https://familysearch.org (June 7, 2017), entry for William E. Kirlew, Apr 12, 1912, citing departure port Kingston, Jamaica, arrival port New York City, New York, New York, ship name Santa Marta; “New York, Index to Petitions for Naturalization filed in New York City, 1792-1989,” database, Ancestry.com, http://Ancestry.com (accessed June 8, 2017) entry for William Kirlew.

3 Milton Vickerman, Crosscurrents: West Indian Immigrants and Race (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 61.

4 "United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918," database with images, FamilySearch.org, https://familysearch.org (7 June 2017), entry for William Emanuel Kirlew, 1917-1918, citing New Britain City no 2, Connecticut, United States.

5 James Tunstead Burtchaell, The Dying of the Light: The Disengagement of Colleges and Universities from Their Christian Churches (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., 1998), 413.

6 Annual Catalogue of Virginia Union University (Richmond, VA: Central Publishing Company Inc., 1918), 68.

7 "United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918," FamilySearch.org; Elias Huzar, “Selective Service Policy 1940-1942,” The Journal of Politics 4, no. 2 (May 1942): 205, doi:10.2307/2125771.

8 Vickerman, Crosscurrents, 94.

9 Mark Ellis, Race, War, and Surveillance: African Americans and the United States Government during World War I (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 14-15.

10 "United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918," FamilySearch.org.

11 War Plans Division, “Training Circular No. 23: Training Regulation for Depot Brigades” (War Department, September 1918), 7, http://cgsc.cdmhost.com/cdm/ref/collection/p4013coll9/id/229.

12 "United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918," database with images, FamilySearch.org, http://familysearch.org (accessed 7 June 2017), entry for William Kirlew.

13 Ellis, Race, War, and Surveillance, 231.

14 Clare Corbould, Becoming African Americans: Black Public Life in Harlem, 1919-1939 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2009), 129–30.

15 "United States Census, 1930," database with images, FamilySearch.org, https://familysearch.org (accessed June 8, 2017), entry for Helen Tynes in household of Harcourt Tynes, Manhattan (Districts 0751-1000), New York, New York, United States; ED 992, sheet 2A, line 44, family 38, NARA microfilm publication T626.

16 The National Archives and Records Administration; Washington, D.C.; “Petitions for Naturalization from the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, 1897-1944,” database with images, Ancestry.com, http://Ancestry.com (accessed June 8, 2017), entry for William Emanuel Kirlew; Series: M1972; Roll: 823.

17 Loretto Dennis Szucs, They Became Americans: Finding Naturalization Records and Ethnic Origins (Salt Lake City: Ancestry Incorporated, 1998), 45–46.

18 “Naturalization from the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, 1897-1944,” Ancestry.com.

19 Huzar, “Selective Service Policy 1940-1942,” 205.

20 George Q. Flynn, “Selective Service and American Blacks During World War II,” The Journal of Negro History 69, no. 1 (1984): 18–20, doi:10.2307/2717656.

21 "United States World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946," database, FamilySearch.org, https://familysearch.org (accessed 7 June, 2017), entry for William E. Kirlew, enlisted 24 Nov 1942, New York City, New York, United States.

22 “U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010,” database, Ancestry.com, https://Ancestry.com (accessed June 12, 2017), entry for William Kirlew.

23 National Cemetery Administration, "William Kirlew," US Department of Veterans Affairs, accessed August 5, 2017, https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/NGLMap?ID=1943369

© 2017, University of Central Florida