Clyde Atwood Emerson (September 22, 1890–January 30, 1919)

By Harrison D. Smith

Early Life

Clyde Atwood Emerson was born on September 22, 1890 in Grand Rapids, Michigan alongside his twin sister, Florence H. Emerson, to mother Julia E. Barber (1869), and father Charles Stafford Emerson, (1869).1 Julia, was born and raised in New York, where she lived until she moved to Michigan, sometime between 1880-1890.2 Born in Ontario, Canada in April of 1869, Charles migrated to Michigan in 1885 to pursue a writing career in America.3 Julia and Charles met in Michigan and married on January 15, 1890.4 Before Clyde turned ten, the Emersons moved to Montgomery, Ohio, probably because Charles took an offer to become a newspaper manager while the twins continued their schooling.5 A few years later, the Emersons migrated to Florida, where it seems they lived in Tampa, Sanford, and Fort Pierce. By 1906, Clyde and Florence both attended high school in Fort Pierce, and participated in local theatrical productions.6

On April 29, 1907, Clyde and Florence’s mother Julia passed away at the age of thirty-eight. The family returned to Michigan for the funeral and burial at Saranac Cemetery in Ionia County, Michigan.7 After high school, Clyde worked as a hotel clerk in the Lenox Hotel in Jacksonville, Florida, while also traveling between Jacksonville and Fort Pierce to perform as an actor and percussionist in an orchestra.8 Clyde married Neticia Austell Lohr on July 3, 1913 in Jacksonville, where Clyde eventually took a job in the Windsor Hotel, pictured here.9 At some point, Clyde and Neticia relocated about one-hundred miles southwest to Marion County where Clyde continued his career in the hospitality industry after taking a job in the luxurious Ocala House Hotel.10 In 1917, he shifted to the public sector, working in the abstract office at the Marion County courthouse.11

Military Service

Like thousands of young men, Clyde registered for the draft on June 5, 1917.12 He continued his work as an abstractor in Ocala until he was inducted into the US Army on February 26, 1918 at age twenty-seven. He departed on February 27, 1918, for Camp Jackson, South Carolina, for basic training.13 Private Emerson joined 20th Company, 5th Training Battalion of the 156th Depot Brigade.14 Over the course of the next few months, Clyde and his regiment likely trained with firearms, explosives, and practiced hand-to-hand combat, which were essential skills needed to survive trench warfare.15 By June of 1918, Clyde rose to the rank of sergeant and joined the 81st Division, 162nd Infantry Regiment, 318th Machine Gun Battalion.16 The 81st Division, better known as the “Wildcats,” was organized in August, 1917, predominantly of men from the southeastern United States.17

Clyde and his regiment traveled to New York City and set sail for England on July 31, 1918 aboard the SS Melita.18 Clyde’s regiment arrived in England in early August to refuel and resupply before heading to the French port of Le Havre and a camp along the coast in Cherbourg. The Division then relocated to Yonne for more training before they mobilized to the Western Front in the Vosges mountain range on September 14, where they were attached to the French 33rd Corps for frontline training within the St. Dié sector. Within days, the 81st Division began to relieve the American 92nd Division occupying the St. Dié sector, on September 18, 1918.19

The 81st Division contained two infantry brigades, the 161st and 162nd; each brigade consisted of two Infantry Regiments and a Machine Gun Battalion.20 Clyde was attached to the headquarters company of the 318th Machine Gun Battalion, which was a part of the 162nd Infantry Brigade alongside the 323rd and 324th Infantry Regiments.21 These personnel were also trained machine gunners that could take up arms in at a moment’s notice if needed.22 Given his background in hospitality and work as an abstractor, Clyde likely worked as a clerk, keeping records for his company, but he just as likely could have served as a runner or as part of a machine gun crew.

After being relieved by the Polish 1st Division, Clyde and the Wildcat Division then moved within the vicinity of Rambervillers to continue training until they arrived near Verdun on October 31, 1918. Here, the 81st prepared to join the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the final major US battle of the war, underway since September 26. The primary objective of the 81st was to take a German supply railroad, the Carignan-Sedan-Mézierés, to render the occupied area of Sedan untenable to the Germans. The Germans fortified this area heavily because it was an essential supply route for their Hindenburg Line. The 81st fought in the Meuse-Argonne until the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918. The 81st sustained 982 casualties during the campaign.23

Following the armistice, the 81st division marched about 175 miles west towards a rest and resupply area near Chaumont, where they remained until moving to Brest and St. Nazaire to sail home in May of 1919.24 During this time, the Spanish Flu became a worldwide pandemic, infecting nearly 500 million people. After four years of war, which destroyed housing, crops, and infrastructure, people were susceptible to illness, which spread quickly among civilians and troops awaiting demobilization. Nearly 1 million American soldiers contracted the flu. Secondary complications like pneumonia further escalated the mortality rate for infected persons, making the spread of influenza even more deadly.25 In January of 1919, Clyde became one of the nearly one million US soldiers to fall ill with influenza.26 After contracting pneumonia, Sergeant Clyde Atwood Emerson died on January 30, 1919, while still in France. He was only twenty-eight years old.27

Legacy

Like so many soldiers that died during and after the war, Clyde’s final resting place is not where he was initially buried. Given the need to identify and bury soldiers quickly to prevent the further spread of disease, soldiers, Americans and others, were initially buried where they died, sometimes on or near battlefields. While many families chose to have their loved ones returned to the US, some opted to bury their loved ones permanently in Europe.28 This enduring presence of fallen American soldiers in France has helped preserve and commemorate the contributions of the US in winning the First World War.

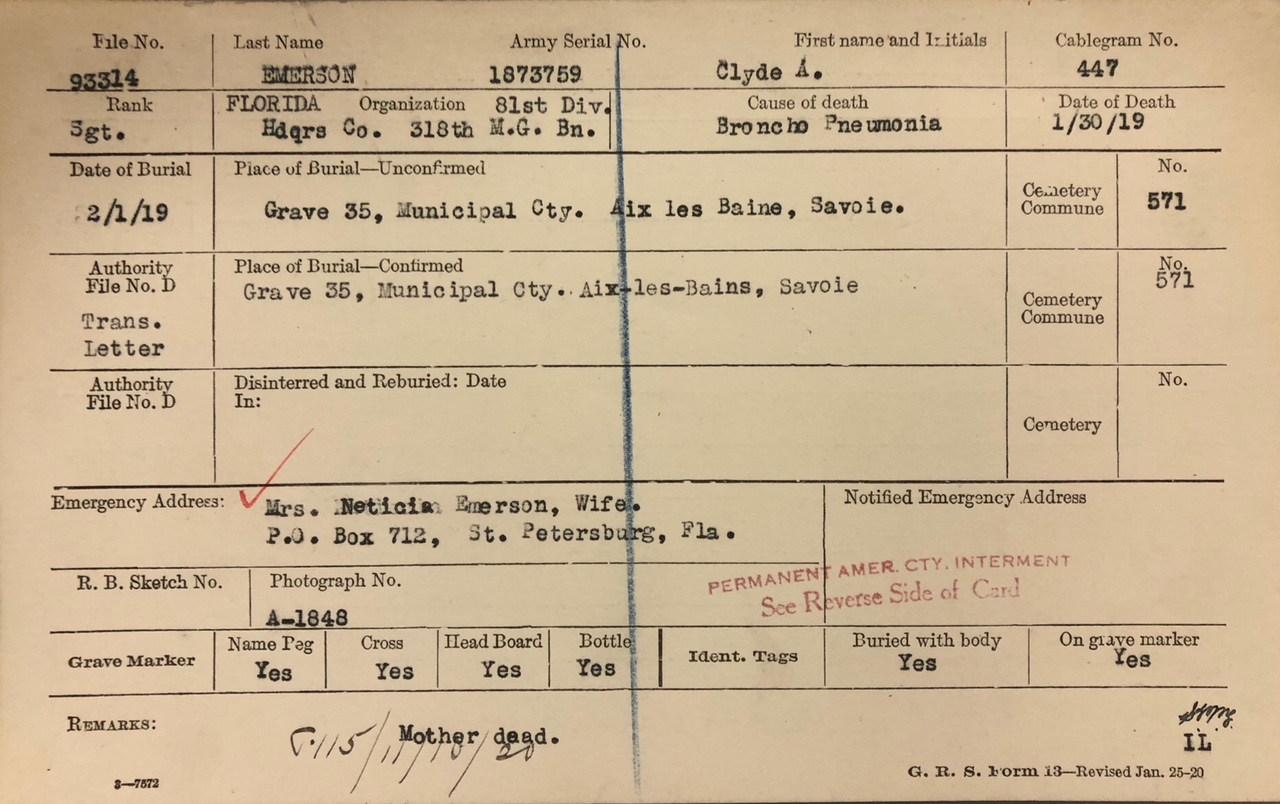

Clyde Emerson was first buried in Grave 65, Municipal City cemetery, in Aix-les-Baines, Savoie, France on February 1, 1919. Here, we see the front side of Clyde’s interment card, which confirms the initial burial location. He was reburied once the US established official American military cemeteries. Clyde Emerson now lays in rest in the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery, Plot B, Row 11, Grave 8, in Belleau, France, where he was reinterred on December 22, 1922.29

Endnotes

1 “1900 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/ accessed February 28, 2018) Entry for Clyde A. Emerson, Montgomery, Ohio, Sheet Number 30, Family Number 349, Line 17.

2 “1880 United States Federal Census” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/ accessed February 28, 2018) Entry for Julia E. Barber, Macedon, Wayne, New York, Sheet Number 11, Family Number 130, Line 44.

3 “1900 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, Entry for Charles S. Emerson; “1920 United States Federal Census” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/ accessed February 28, 2018 Entry for Charles S. Emerson, Duval, Jacksonville, Florida, Sheet Number 54, Family Number 846.

4 “Michigan Marriage Records (1867-1952)” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/ accessed February, 18, 2018) Entry for Charles S. Emerson, Julia E, Barber, Kent, Michigan, Date Jan 15 1890, Record Number 2554.

5 “1900 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, Entry for Charles S. Emerson.

6 “Fort Pierce High School Notes,” The St. Lucie County Tribune, Feb 23, 1906, page 8, Newspapers.com; “Pleasant Party on River Front,” The St. Lucie County Tribune, February 2, 1906, page 1, Newspapers.com ; “Former Tampa Lady Dies At Her Sanford Home,” The Weekly Tribune, May 02, 1907, page 3, Newspapers.com; Ruth Alderman, “Little Ones On The Stage,” The Tampa Tribune, Nov 1, 1906, page 5, Newspapers.com.

7 “Former Tampa Lady Dies At Her Sanford Home,” The Weekly Tribune, May 02, 1907, page 3, Newspapers.com; "Julia E Barber Emerson (1870-1907), Find A Grave Memorial, (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/33667083/julia-e-emerson. Accessed February 28, 2018).

8 “1910 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/ accessed February 28, 2018) Entry for Clyde A. Emerson, Jacksonville, Florida, Sheet Number 26, Family Number 24, Line 96; “Local,” Fort Pierce News, May 27, 1910, page 5, Newspapers.com.

9 “Florida, County Marriages, 1830-1957,” database, Familysearch.org, (https://familysearch.org/ accessed March 09, 2018) Entry for Clyde A. Emerson, 417; “U.S. City Directories 1822-1995,” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/ accessed February 28, 2018). Entry for Clyde A. Emerson, Jacksonville, Florida, Sheet Number 204, Line 44.

10 “Ocala House Improvements,” The Ocala Evening Star, March 7, 1914, page 8, Newspapers.com.

11 “Inverness”, The Tampa Tribune, March 02, 1919, page 25, Newspapers.com.

12 “U.S. World War I Draft Registration Cards 1917-1918” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com accessed February 28, 2018) Entry for Clyde A. Emerson, Monroe County, Florida, Draft Card E, Sheet Number 52.

13 “U.S. Lists of Men Ordered to Report to Local Board for Military Duty 1917-1918” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/ accessed February 28, 2018) Entry for Clyde A. Emerson, Marion County, Florida, Sheet Number 189, Order Number 908, Serial Number 1137.

14 “WWI Service Cards,” Floridamemory.com (https://www.floridamemory.com: accessed on February 26, 2018), entry for Clyde A. Emerson.

15 Jennifer D. Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 52-54.

16 “WWI Service Cards” Floridamemory.com.

17 American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC), 81st Division Summary Of Operations In The World War, (Washington D.C., United States Printing Office, 1944), 1.

18 “U.S. Army Transport Service Passenger Lists 1910-1939” Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/ accessed February 28, 2018) Entry for Clyde A. Emerson, Outgoing, Melita, 22 Jan 1919 – Sept 1931.

19 ABMC, 81st Division Summary Of Operations In The World War, 1-4.

20 ABMC, 81st Division Summary Of Operations In The World War, 1.

21 ABMC, 81st Division Summary Of Operations In The World War, 12; “WWI Service Cards,” Floridamemory.com, entry for Clyde A. Emerson.

22 George Raach, A Withering Fire, (Bradenton, Florida: Booklocker.com, 2015), 320 Kindle Version.

23 ABMC, 81st Division Summary Of Operations In The World War, 7-22.

24 ABMC, 81st Division Summary Of Operations In The World War, 21.

25 Keene, World War I, 164.

26 Keene, World War I, 165; ABMC, 881st Division Summary Of Operations In The World War, 21.

27 “American Soldiers of World War I” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/ accessed February 28, 2018) Entry for Clyde A. Emerson, Soldiers Of The Great War Volume 1, Florida, Page Number 193/7, Title – Died Of Disease, Sergeants.

28 Keene, World War I, 192.

29 "Clyde A. Emerson." Clyde A. Emerson, American Battle Monuments Commission. Accessed March 16, 2018. https://www.abmc.gov/node/340562; Interment Card, File 93314, Army Serial No. 1873759, Clyde A. Emerson, Sergeant, 81st Infantry Division, Headquarters Company, 318th Machine Gun Battalion; Card Register of Burials of Deceased American Soldiers, 1917-1922, Entry NM-81 1945; Records of the Office of the Quartermaster General, 1774-1985, Record Group 92; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.

© 2018, University of Central Florida