Leroy “Ian” Brandon (June 10, 1897–June 6, 1918)

By Andrew Mickelberry

Early Life

Leroy “Ian” Brandon was born on June 10, 1897 in Clearwater, Florida to parents Leroy John Brandon and Mary Isabell Reynolds.1 Ian had three sisters, Mabel, Judith, and Sadie.2 His father was a Pinellas County Judge in the 1910s and through the 1920s. Judge Leroy John Brandon was the son of John Brandon, the founder and namesake of Brandon, Florida, located in Hillsborough County.3 Judge Brandon served as mayor of Clearwater from 1907 to 1909.4 Raised in Clearwater, Ian and his siblings all graduated from high school.5 By 1917, Ian lived a rather normal life for a prominent Clearwater family, except that he made the choice to enlist in the Marine Corps in February 1917.6

Military Service

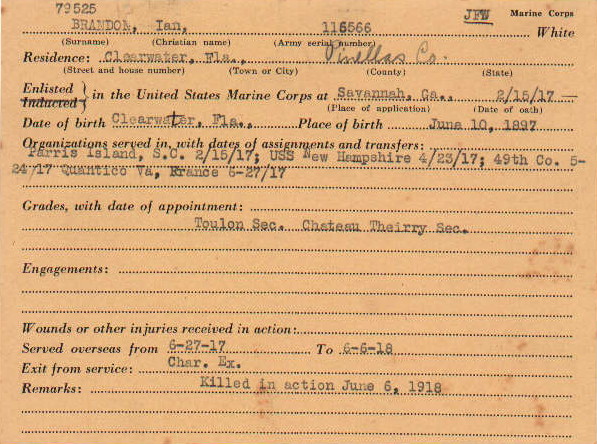

According to his service card, pictured here, Ian enlisted in the Marines at Savannah, Georgia, on February 15, 1917.7 The desire to enlist and serve one’s country must have been great for Ian as he did so before the US declared war in April. Moreover, the Brandon family had a history of service in the military. His grandfather and several uncles had fought in the Civil War.8 After enlisting in Savannah, Ian traveled to Parris Island, South Carolina, for training.9 By the time he finished basic training the US was at war.10 Ian was among the first American troops, seventy officers and 2,689 enlisted men, to go to France.11 The Tampa Tribune called Ian a “First to Fight” Marine, praising him for his marked ability and performance during his training.12 Ian joined the 49th Co. of 1st Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment.13 The Marines reactivated the 1st Battalion on May 25, 1917. By June 14, Ian and the 5th Regiment embarked for the port of St.Nazaire, France, arriving several weeks later. By July 3 the entire 5th regiment was ashore in France, and began training in their assigned regions. Ian and his fellow Marines trained alongside the French “Blue Devils,” the Alpine Chasseurs. The Alpine Chasseurs were adept French troops with a long history of battle and bravery.14

In October of 1917, the 5th Regiment combined with the 6th Marine Regiment and 6th Machine Gun Battalion to form the 4th Marine Brigade. The 4th Marine Brigade then served as part of the Army’s 2nd Division until late 1919, when U.S. troops headed home. The newly formed 4th Marine Brigade, based in Bourmont, about 65 kilometers behind the Verdun section of the front, continued training. The 4th Marine Brigade trained until March 1918 when the German Army launched its final major offensives meant to break through Allied lines and end the war. The 4th Marine Brigade played an instrumental role holding back Germany’s offensive push. In late May 1918, the 4th Marine Brigade arrived at the Château-Thierry sector to stop the German push for Paris. The Marines were met by demoralized French troops who had been fighting for four long years. Aside from offering much needed reinforcements, the American troops offered a boost of morale that France needed.15 Ian and his fellow Marines must have been, without a doubt, itching for a fight and singing American songs, filled with confidence and determination.

When advancing German forces created a hole in the French front at Belleau Wood, the Marines were ordered to stop them.16 The Germans used the thick, wooded area to amass troops and fortified it as a defensive position. Only a small wheat field and a ridge known as Hill 142 stood between the Marines and the advancing Germans. At 3:45 in the morning of June 6, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment began an assault on Hill 142. With only two companies in position, Ian and his fellow Marines advanced across the open wheat field under heavy German fire.17 Later that day, the remaining Marine units advanced on Belleau Wood itself. Attacking these German held positions came at great cost. More Marines were lost on June 6, 1918 than any previous day in the Corps’ history.18 Thirty-one officers and 1,056 enlisted men died in this initial effort to stop the Germans from piercing through the Allied lines and reaching Paris.19Private Ian Brandon was among the men who gave their lives that day.20 His comrades in the 5th Marine Regiment continued to fight for several weeks, taking the wood at the end of the month, and then fighting until July 5th when they were relieved from the front line.21

Legacy

Ian’s body was never recovered. He is memorialized on the Tablets of the Missing at the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery, located at the foot of Belleau Wood.22 The legacy of Belleau Wood remains central to the Marine Corps’ identity. Pictured here, is a view from the German positions in the wood, looking out over the wheat field where Ian and over a thousand other Marines lost their lives on June 6, 1918, taken 100 years later. Today, Belleau Wood is a pilgrimage site for Marines, a place they pay respect to their brothers-in-arms from a century ago.23 Belleau Wood is important to other Americans and French who visit the site as well, due to the determination and fighting spirit displayed by men like Leroy Ian Brandon.

Beginning in 1921, the new American Legion post in Clearwater, Florida chose to remember Ian’s sacrifice by taking his name. The Veterans who founded the Turner-Brandon post chose to honor Ian Brandon and a sailor named Edward Turner, citing them as “men of pioneer stock.”24 Fitting words as Ian Brandon would have done much more for his country had he returned home.

Endnotes

1 “World War 1 Service Card.” Database. Floridamemory.com (https://www.floridamemory.com), entry for Ian Brandon, Army Serial Number 116566.

2 “1910 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/, accessed 26 March, 2018), Entry for Ian Brandon, District 0022, Florida.

3 Andrew Mickelberry, correspondence with Patrick McCann, cousin of Ian Brandon, March 2018; On Ian’s father, Judge LeRoy John Brandon, see Findagrave.com, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/23524606/leroy-john-brandon. For Ian’s grandfather, John Brandon, see: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/8814103/john-william-brandon.

4 Correspondence with Patrick McCann.

5 “1910 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com

6 “World War 1 Service Card.” Database. Floridamemory.com

7 “World War 1 Service Card.” Database. Floridamemory.com

8 Correspondence with Patrick McCann.

9 “World War 1 Service Card.” Database. Floridamemory.com.

10 “World War 1 Service Card.” Database. Floridamemory.com.

11 George B. Clark, Devil Dogs (Navato: Presidio Press, 1999), 2.

12 “St. Pete Loses the County Board Trade,” Tampa Tribune, August 7, 1917. Page 5, newspapers.com

13 World War 1 Service Card.” Database. Floridamemory.com.

14 Clark, Devil Dogs, 2-3, 28-29, 36.

15 Clark, Devil Dogs, 33, 36, 66-67, 69.

16 Clark, Devil Dogs, 74-75.

17 Robert B. Asprey, At Belleau Wood (Denton, UNT Press, 1996), 144-145.

18 Clark, Devil Dogs, 101.

19 Asprey, At Belleau Wood, 154.

20 “World War 1 Service Card.” Database. Floridamemory.com.

21 Clark, Devil Dogs, 205.

22 “Ian Brandon,” Database, American Battle Monuments Commission (https://www.abmc.gov).

23Michael C. Howard, “Belleau Wood Pilgrimage,” Marine Corps Gazette 86, No. 6 (June 2002), (https://www.mca-marines.org/gazette/2002/06/belleau-wood-pilgrimage: accessed June 8, 2018).

24 “A Brief History of Turner-Brandon Post 7.” The American Legion (https://centennial.legion.org/florida/post7?p=about: accessed September 23, 2018). After the war, Clearwater veterans “planned the formation of an American Legion Post” named for two area veterans who died during the war. Turner, who served in the Navy, died at sea on the USS Rhodes Island.

© 2018, University of Central Florida