Paul Hon (July 1898–July 20, 1918)

by Elizabeth Klements

Early Life

Paul Hon was born in 1898 to Edmond and Lulu Hon in Orleans, Indiana.1 He was the couple’s first son, and the third of eight children, named Ruth (1892), Gladys (1895), Paul (1898), Howard (1900), Theodore (1902), Ray (1904), Lois (1906), and Dorothy (1915).2 A bookkeeper in Orleans, Edmond moved his family to DeLand, Florida, in 1900 to work for John B. Stetson.3 Stetson, the inventor of the famous “Stetson” cowboy hat, had built a winter home in the recently established town of DeLand.4 At some point, Edmond Hon met J.B. Stetson in Orleans through Elizabeth Shindler, an Orleans resident who married Stetson in 1884. At her suggestion, Stetson offered Hon a position as bookkeeper, and later manager, of his DeLand estates.5 Edmond Hon prospered in DeLand, where he sat on the Stetson University Board of Trustees and set up his own Real Estate and Insurance Agencies. When he died in 1948, Stetson University bought his home and converted it into the Hon Residence Hall, in honor of his contributions to the school.6 The Tampa Tribune society pages mentioned Edmond Hon and his family on several occasions in the early twentieth century.7

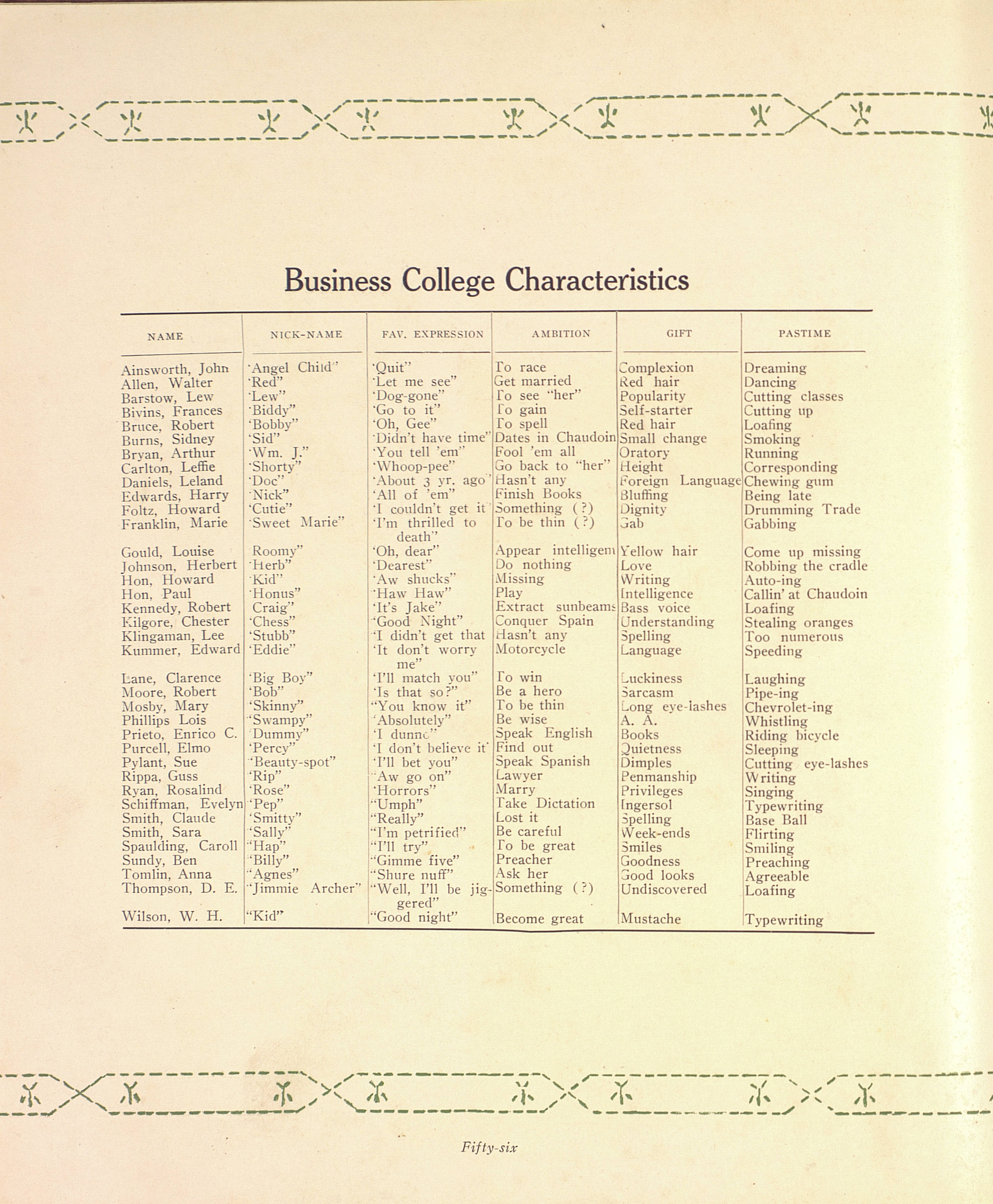

Paul Hon entered Stetson University as a freshman in 1916, serving as the Chairman of the freshman class social committee, though he had been involved in the Stetson University community prior to his enrollment.8 In 1915, Paul served as president of the Stetson Literary Society, an organization reserved for “the academy children.” Paul was also part of the baseball team and pledged the Phi Kappa Delta fraternity.9 As a freshman, Paul joined the Green Room Club, a theater group with which he performed a role in Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night’s Dream.10 He entered the College of Business his sophomore year, serving as president of his class and as a member of the Stetson Choir.11 All sources indicate he was a lively and outgoing student. A page in the 1917 Stetson Yearbook, pictured here, describing the members of the Business College claimed that Paul’s ambition was to “play,” his gift was “intelligence,” and his favorite pastime was “callin’ at Chaudoin” Hall, a women’s-only residence on campus.12

Military Service

On April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. On May 10, Paul enlisted at Fort Screven, Georgia, as a private.13 Eighteen years old, Paul had just finished his sophomore year at Stetson University. Many men volunteered so that they could choose their branch of service, a choice not afforded to draftees. Although he was educated, volunteered for service, and came from a prominent white family, Paul did not become an officer, even though there was a shortage of officers when the US entered the war.14 While the reason Paul did not earn a commission is unclear, perhaps he did not pass the exam, or he may not have been interested in becoming an officer, despite having two years of college. Since President Wilson did not officially authorize conscription until May 18 – eight days after Paul enlisted – the surge of patriotism, the call of adventure and heroism, and the desire to prove himself a man all may have motivated Paul’s decision.

Paul entered the Engineering Corps, where he joined Company B, 1st Engineers, which was part of the 1st Army Division.15 The Engineer Corps was responsible for facilitating the American Expeditionary Forces’ (AEF) transportation to the front lines, by building roads, railroads, and bridges. Engineering units attached to divisions, like Paul’s, often went with the infantry into combat, scouting the terrain, repairing trenches, and providing armed support.16 Paul’s training took place in Washington DC and lasted about three months. His division shipped out to France on August 7, 1917, and arrived safely in St. Nazaire, France, at the end of the month, despite a skirmish with German submarines just outside the Atlantic port city.17

After arriving in France, Paul, having been selected from a pool of 1,064 other applicants, went to Chatham, England, in September, “to take a four weeks’ course with the Royal Engineers,” before returning “to France to be placed at the head of his corps.”18 Under the Royal Engineers, Paul learned “the use of defensive articles against gas attacks.”19 The German forces introduced poison gas in 1915, and, by 1917, all sides used a diverse range of chemical weapons. Survival in a poison gas attack depended on the soldier’s ability to identify the gas and respond appropriately.20

After returning to France, Paul rejoined the 1st Engineers and spent the next four months training with the French in Lunéville, a relatively quiet sector of the front, north of the Vosges Mountains. In January, they moved north and west to the Ménil-la-Tour sector, where they fortified the trenches, repaired roads, and constructed command posts. In April, the division travelled over 300 kilometers to Cantigny, a more active sector, and again engaged in repairing the defensive positions. This time they faced “very trying conditions,” including heavy shelling and the threat of an enemy offensive.21 In May 1918, Paul earned the rank of Sergeant.22

In July, the 1st Engineers participated in the Aisne-Marne campaign, or the second battle of the Marne.23 The German forces launched an offensive to the northwest of Paris in May, with US troops engaging in front line fighting at Château Thierry. For the second time since 1914, the Germans had pushed their line out into a bulge that spanned roughly thirty-seven miles at its base, and pointed toward Paris.24

The American 1st and 2nd Divisions received orders to aid the French, under the command of General Charles Mangin’s 10th Army, to push back the German assault near Soissons.25 Paul and the 1st Engineers served as infantry reserves for the 1st Division.26 On the night of July 17, into the early morning of July 18, American and French troops moved under the cover of darkness to the front lines in order to surprise the Germans.27 Paul’s company received orders to assist in the attack. On July 18, it advanced with an infantry battalion, moving south of Soissons, and digging in overnight. The next morning it received orders to advance with the 16th Infantry Battalion; the soldiers passed the Paris-Soissons road and dug in again. By this point, nine men in Paul’s company were wounded, including one of the captains. On July 20, Company B continued its advance toward Soissons with the 16th Infantry; sixty-two men were wounded or killed, including Paul Hon.28 Thomas B. Kauffman, who served with Paul, later noted in a letter home that Paul “died in battle leading his platoon into a charge against the Germans.”29 His company remained on the front lines one more day; a Scottish Division relieved them on July 22.30 The Aisne-Marne Campaign did not end until August 6, when the Germans surrendered their bulge of territory.31

Legacy

Paul Hon died on the battlefield on July 20, around his twentieth birthday.32 His remains were never recovered or identified. We commemorate him on the Tablets of the Missing in the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery in Belleau, France.33 Paul’s obituary in The Tampa Tribune states that Paul could have stayed away from danger as an “instructor in a British school of mine engineering,” but chose not to, and “was granted the request to go back to his regiment and into the fight.”34 By the time of Paul’s death, DeLand had already lost three African-American soldiers to the influenza epidemic; Paul became DeLand’s fourth fallen son.35 His wide circle of friends and acquaintances certainly must have felt the devastating loss of the war. Above all, this pain must have affected Paul’s family, who, having just lost their son faced the prospect of losing a second son, Howard, whose division arrived in France within a few days of Paul’s death.36

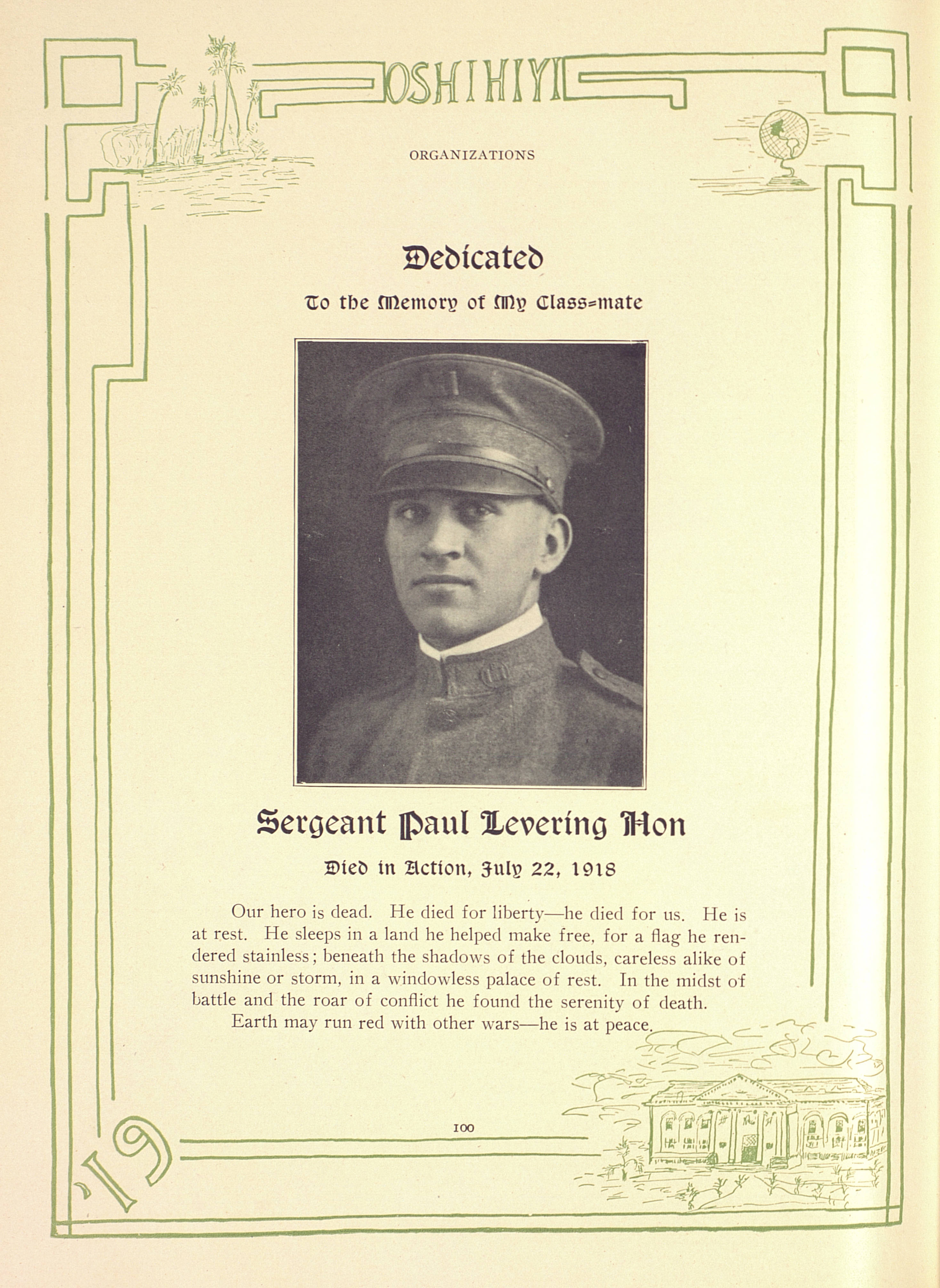

Paul Hon was a beloved member of his community. All the churches of DeLand united to give Paul a special memorial service, demonstrating the weight of Paul’s death on the community, as well as the community’s effort to remember his service. In 1919, the Stetson University Yearbook published a memorial page, pictured here, for Paul, with the following passage: “Our hero is dead. He died for liberty – he died for us…Earth may turn red with other wars – he is at peace.”37

Endnotes

1 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 25, 2018), entry for Paul Hon, Orleans, Orange, Indiana; “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 25, 2018), entry for Paul Hon, DeLand, Volusia, Florida.

2 “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 25, 2018), entry for Edmond L.Hon, DeLand, Volusia, Florida.

3 “1900 Census,” entry for Paul Hon, Orleans, Indiana; “1920 Census,” entry for Edmond L.Hon; Ange Shurley, “Colorful Hon Hall Bites The Dust,” The Stetson Reporter, (DeLand, Florida), May 19, 1967, 13, http://digital.archives.stetson.edu/cdm/ref/collection/Newspapers/id/6741.

4 Gilbert Lycan, Stetson University: The First 100 Years, (DeLand, Florida: Stetson University Press, 1983), 13; Maggi Smith Hall, Stetson University, (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2005), 20.

5 Daphne M. Brownell, “The Daphne M. Brownell Collection,” entry for Hon, notebook 026, Genealogy/ Local History Collection, DeLand Public Library, DeLand, Florida; “Widow of John B. Stetson,” The Indianapolis Star, October 20, 1911, Newspapers.com.

6 Gerri Bauer, “Hon Hall Gone But Memories Remain Strong,” The Stetson University Magazine, Fall/Winter 2006: 28-30, database, Stetson University Archives (http://digital.archives.stetson.edu/cdm/ref/collection/Unidocs/id/37240: accessed September 23, 2018); “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 25, 2018), entry for Edmond Hon, DeLand, Volusia, Florida; Hon hall was the private residence of E. L. Hon until his death in 1948, at which time, Stetson University purchased the home for use as a dormitory. The Stetson University duPont-Ball Library provided invaluable information and assistance throughout the research and writing of this biography. Special thanks go to Susan Ryan, Dean of the duPont-Ball Library and Learning Technologies, and to Stetson University archivist Kelly Larson for granting UCF permission to publish their documents, and for their time and assistance.

7 For examples, see “South Florida Social Notes,” The Tampa Tribune, March 5, 1918, page 9, Newspapers.com; “Social Doings in South Florida,” The Tampa Tribune, September 3, 1911, 24, Newspapers.com.

8 “Freshman Class” Oshihiyi 1916, 49, database, Stetson University Archives, DeLand, Florida, http://digital.archives.stetson.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/Yearbooks/id/22957.

9 “Stetson Literary Society,” Oshihiyi 1915, 94, database, Stetson University Archives, DeLand, Florida, http://digital.archives.stetson.edu/cdm/ref/collection/Yearbooks/id/22669; “The Baseball Team,” Oshihiyi 1915, 130, database, Stetson University Archives, DeLand, Florida, http://digital.archives.stetson.edu/cdm/ref/collection/Yearbooks/id/22705; “Phi Kappa Delta,” Oshihiyi 1915, 112, database, Stetson University Archives, DeLand, Florida, http://digital.archives.stetson.edu/cdm/ref/collection/Yearbooks/id/22687.

10 “The Green Room Club of The John B. Stetson University Presents the Comedy A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” Oshihiyi 1917, 67, database, Stetson University Archives, DeLand, Florida, http://digital.archives.stetson.edu/cdm/ref/collection/Yearbooks/id/22471.

11 “Sophomore Class,” Oshihiyi 1917, 45, database, Stetson University Archives, DeLand, Florida, http://digital.archives.stetson.edu/cdm/ref/collection/Yearbooks/id/22449; “Choir,” Oshihiyi 1917, 61, database, Stetson University Archives, DeLand, Florida, http://digital.archives.stetson.edu/cdm/ref/collection/Yearbooks/id/22465.

12 “Business College Characteristics,” Oshihiyi 1917, 56, database, Stetson University Archives, database, Stetson University Archives, DeLand, Florida, http://digital.archives.stetson.edu/cdm/ref/collection/Yearbooks/id/22460; Hall, Stetson University, 21.

13 “WWI Service Cards,” database, FloridaMemory.com, (http://www.floridamemory.com: accessed March 25, 2018), entry for Paul Hon, Army Serial Number 154998.

14 Jennifer D. Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience, (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 39-60.

15 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Paul Hon; Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War, American Expeditionary Forces: Divisions. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1988, 2.

16 Keene, World War I, 154-155.

17 “U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger List, 1910-1939,” database, Ancestry.com, (http://www.ancestry.com accessed April 8, 2018), entry for Paul Hon; Thomas F. Farrell, et al. eds., A History of the 1st US Engineers 1st US Division, (Coblenz, Germany, 1919), 5-8.

18 “Eustis,” The Tampa Tribune, September 30, 1917, 22, Newspapers.com.

19 “Our Juniors in the Service,” Oshihiyi 1918, 106, database, Stetson University Archives, database, Stetson University Archives, DeLand, Florida, http://digital.archives.stetson.edu/cdm/ref/collection/Yearbooks/id/23948.

20 Keene, World War I, 142-143. The threat posed by chemical weapon attacks was a prolonged one. Gas would linger in trenches and craters, and thus posed a constant threat, even when no recent attack was evident.

21 Farrell, A History of the 1st US Engineers, 11-22.

22 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Paul Hon.

23 Farrell, A History of the 1st US Engineers, 23.

24 Edward M. Coffman, The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I, (Lexington KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1998), 234.

25 Coffman, The War to End All Wars, 234-235.

26 Farrell, A History of the 1st US Engineers, 24.

27 Coffman, The War to End All Wars, 236; Farrell, A History of the 1st US Engineers, 23-24.

28 Farrell, A History of the 1st US Engineers, 24-26.

29 “Kauffman Made Color Sergeant Of Regiment,” The Tampa Tribune, November 10, 1918, 9, Newspapers.com.

30 Farrell, A History of the 1st US Engineers, 26.

31 Douglas V. Johnson and Rolfe L. Hillman Jr, Soissons, 1918, (College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 1999), 141.

32 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, entry for Paul Hon.

33 “Paul L. Hon,” American Battle Monuments Commission, (https://www.abmc.gov/node/346636: accessed March 26, 2018)

© 2018, University of Central Florida