Ben Davis (May 25, 1895–December 28, 1947)

By Shmuel Kilstein and Gramond McPherson

Early Life

Ben Davis was born in Charleston, SC, on May 25, 1895.1 As with many African Americans born in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, few records exist that help us trace his early life and family. Due to structural discrimination in American society, whites often did not see the need to document African-American lives, especially in the South. Prior to 1915, the state of South Carolina did not require the issuance of birth certificates and for many African Americans like Davis, family items like Bibles may have contained their only record of birth.2 Additionally, while documentation of newly emancipated African Americans increased after 1870, the federal census, which occurs every ten years, often undercounted the black population in the early nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.3

As an African American man living in the South, Davis grew up in an era where white-controlled governments in states like South Carolina expanded discriminatory polices legalizing the already customary subordination of African Americans. Known as Jim Crow, these laws affected the daily lives of black Americans through disfranchisement (or the stripping of voting rights), the maintenance of residential segregation, and the enforcement of racial segregation in public facilities, public transportation, and schools.4 Concerning education, many black children like Davis received less education compared to their white counterparts. Schools for black children were segregated and underfunded with secondhand books and supplies, overcrowded classrooms, and less qualified teachers. Despite educational inequalities, many black parents sought to ensure their children received the best education possible. While a large percentage of black children like Davis only received an elementary school education, this provided them with basic literacy skills important in life.5

While we are unsure when he relocated to Florida, by 1917 Davis settled in Clearwater, located in the Tampa Bay area. While Jim Crow remained in force in Florida, African Americans flocked to the state during the early twentieth century seeking better economic opportunities. During the First Great Migration, which occurred during and after World War I, blacks migrated from the Lower South to Northern cities like Detroit and New York, while other blacks migrated to Florida. For black Southerners, Florida was closer than the North, had a warmer climate, and, most importantly, had growing opportunities in service and labor jobs. Railroads helped facilitate labor recruitment and black migration to cities like Miami, Jacksonville, and Tampa. In Clearwater, Davis found employment working for H.K. Cheney, likely his white employer.6

Military Service

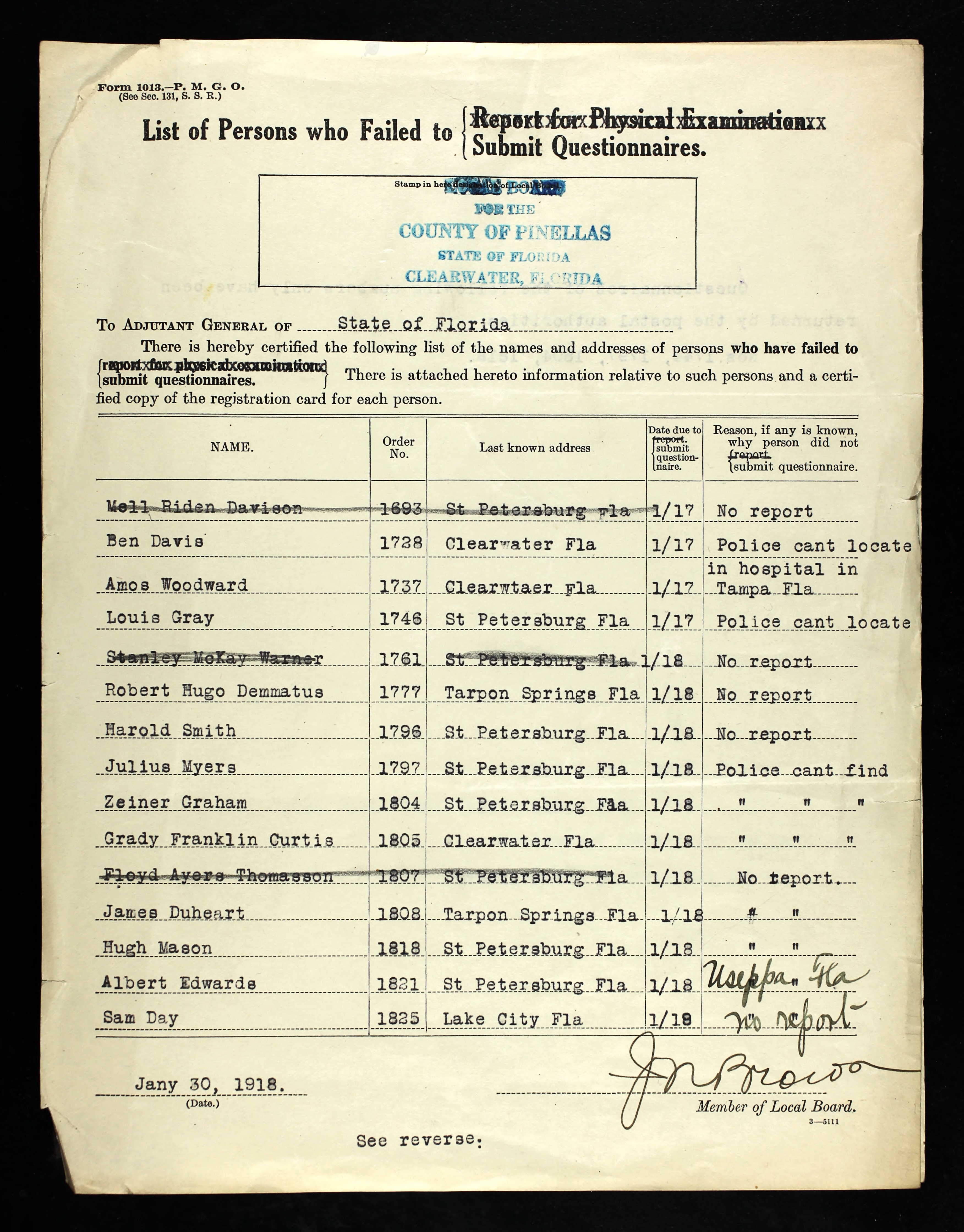

Shortly after Woodrow Wilson’s declaration of war in April 1917, Congress passed the Selective Service Act to raise manpower quickly for the military through conscription. The first registration on June 5, 1917, required all men between twenty-one and thirty years of age to register for the military draft. Davis, in his early twenties, fulfilled his duty in registering with local authorities in Pinellas County.7 The Selective Service Department established district boards through each state with jurisdiction over numerous local draft boards. Draft boards collected information and sent notices to registrants. One long form asked about every aspect of registrants’ lives.8 Moreover, those who failed to return the form within seven days faced police inquires. The draft board often gave delinquents’ names to the police, who could seek them out and report their status.9 When Davis failed to submit his questionnaire by January 17, 1918, Pinellas County’s draft board, as seen here, listed him among those who failed to submit their questionnaire on time, with a note that the police had failed to locate him by January 30.10

We should not jump to conclusions about why Davis initially failed to comply with the draft board. For some potential white and black draftees, limited literacy prevented them from fully complying with orders. Others invoked their religious beliefs in questioning the purpose of the war. Furthermore, in the rural South, white landlords, seeking to maintain control over their black workforce, purposely withheld or refused to read notices from the local draft board. In some cases, white landlords withheld information so they could take advantage of the opportunity to collect fifty dollars in reporting so-called deserters.11 While we are unsure why Davis failed to submit his questionnaire, he probably did not purposefully attempt to evade military service. In most cases, African Americans were unaware of the requirements for a variety of reasons, or moved frequently, which led to a higher percentage of ‘desertions’ among blacks in the South compared to whites.12 The penalty for failing to submit a questionnaire resulted in a registrant waiving his claims for deferred classification, and made these men eligible for immediate service.13 Race played a major factor in a higher percentage of blacks, especially in the South, being classified for immediate service despite legitimate claims for deferral, that some black men undoubtedly made, to remain in the US to support their families.14

The Army eventually found Davis, and inducted him on August 1, 1918.15 Initially, the Army planned to assign all draftees to training camps near their place of residence to reduce the cost of transporting soldiers. Yet, in maintaining white supremacy, the Army also sought to ensure a white majority at each training camp. While training at the same bases as whites, segregation remained in force. As the South contained the highest concentration of African Americans in the country, the Army sent many Southern black draftees like Davis to bases far away in the North to maintain racial quotas.16 Therefore, the Army sent Davis to train at Camp Devens, MA, where he remained for the duration of his service.17 Established in September of 1917, Camp Devens, one of the sixteen cantonment or temporary training camps built during World War I, intended to prepare troops for overseas deployment because of its proximity to the Boston & Maine Railroad.18

Upon arriving at Camp Devens, Davis joined the 151st Depot Brigade. New soldiers like Davis often served in depot brigades during their initial period of processing, training, and indoctrination into the Army. Once trained, recruits were assigned to an operational unit. In the segregated Army, black troops served in all-black companies.19 During his training, Davis likely saw firsthand the impact of an influenza outbreak at Camp Devens in September 1918, which infected over 10,000 soldiers and killed around 800.20 After three months in the 151st Depot Brigade, Davis, joined the newly formed 443rd Reserve Service Battalion on November 1, 1918 until his discharge.21 Davis, like most black soldiers during the war, served in noncombatant units (Service, Engineer, and Pioneer Infantry) with minimal to no firearms training. In this way, the Army balanced its need for manpower with the need to satisfy concerns among white-civilian and government officials, who expressed fears that armed black soldiers would use their military training to start a racial war upon returning home.22

Of the 370,000 African Americans drafted for military service, about 170,000 remained in the US during the war, performing various labor duties at training camps across the country. At Camp Devens, Davis likely constructed buildings, chopped wood, loaded ships, hauled materials, or did other manual labor.23 While many black troops found these duties demeaning, black labor troops both in the US and overseas played an important role in the overall war effort.24 When the war ended with an armistice on November 11, 1918, Davis and the 443rd Reserve Service Battalion continued to work for about six months, participating in the demobilization of millions of troops returning from France.25 On May 30, 1919, Davis received an honorable discharge from the Army, leaving with the rank of Private First Class.26

Post-Service Life

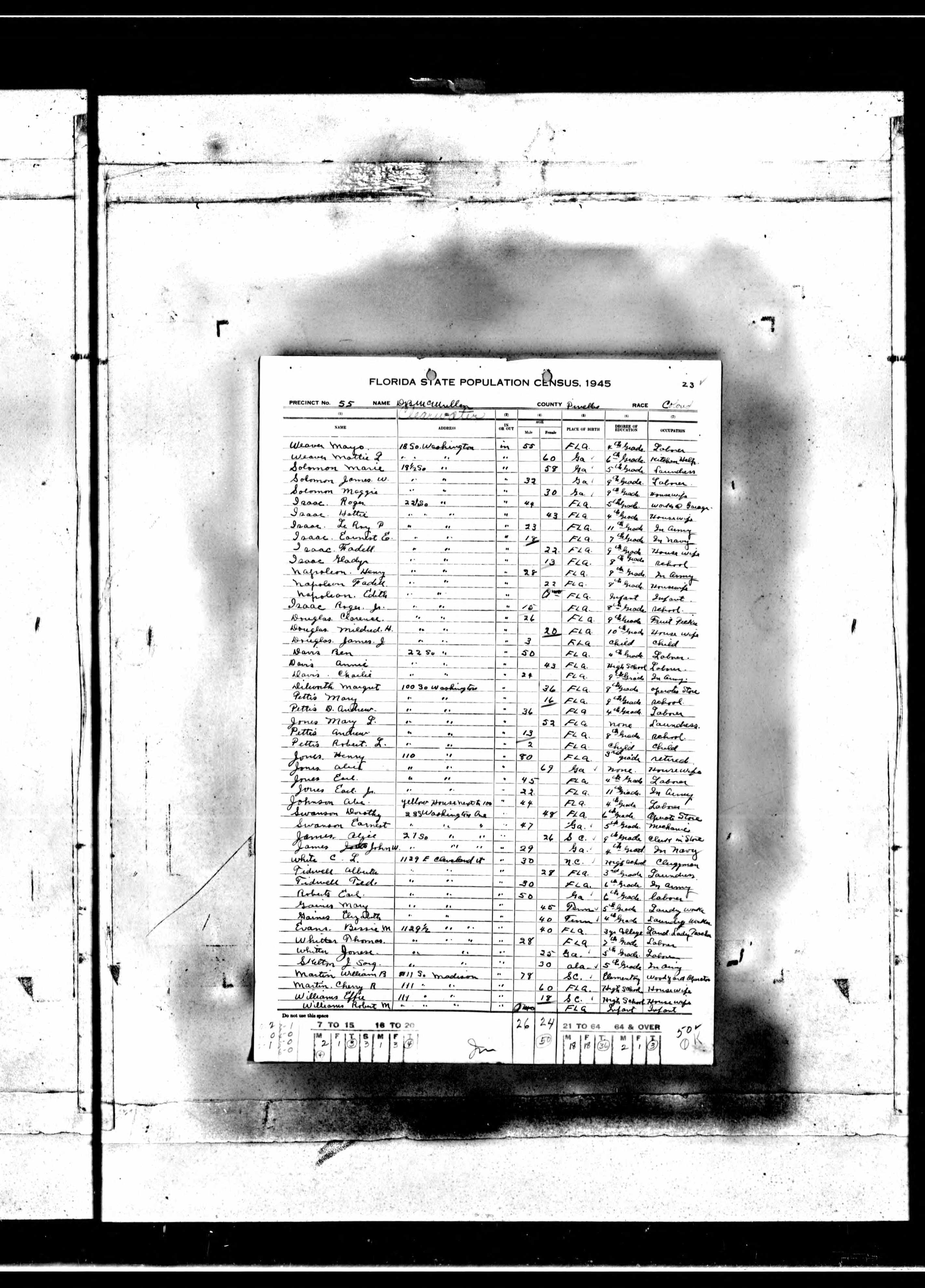

After the war, Ben returned to Clearwater and continued to work as a laborer.27 On October 20, 1944, he married Annie R. Leach, a native of Gainesville, FL and a widow, who also lived in Clearwater.28 The 1945 state census lists Davis and his wife Annie (line 19) in Clearwater, as seen here, along with a male relative named Charlie who served in the segregated Army during World War II.29 Davis died on December 28, 1947. He is buried at the Bay Pines National Cemetery in St. Petersburg, FL in Section 6, Row 3, Site 16.30

Endnotes

1 We are using the birthdate on Davis’s headstone. His World War I registration card lists his birthdate as June 26, 1893, while his World War I service card lists his date of birth as August 15, 1891. May 25, 1895 is typed on his official headstone application the form, but is crossed out and replaced with August 15, 1891. “U.S. World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed March 25, 2019), entry for Ben Davis; “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com (https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/210980: accessed August 8, 2019), entry for Ben Davis; “U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com/: accessed March 25, 2019), entry for Ben Davis.

2 Damon L. Fordham, True Stories of Black South Carolina (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2012) Kindle edition, chap. The Other Side of Mepkin.

3 “African Americans in the Federal Census, 1790–1930,” National Archives, accessed August 7, 2019, https://www.archives.gov/files/research/census/african-american/african-american-census-research.ppt.

4 Leon F. Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York: Vintage Books, 1999), 228–34.

5 Russell Brooker, The American Civil Rights Movement 1865-1950: Black Agency and People of Good Will (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2017), 41-42; John L. Rury, Education and Social Change: Themes in the History of American Schooling (Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates, 2002) 167.

“Florida, State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com/: accessed March 25, 2019), entry for Ben Davis, Pinellas County, FL, 1945.

6 “U.S. WWI Civilian Draft Registrations,” Ancestry.com, Ben Davis; Steven A Reich, ed., The Great Black Migration: A Historical Encyclopedia of the American Mosaic (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2014), 207.

7 “U.S. WWI Civilian Draft Registrations,” Ancestry.com, Ben Davis; Jennifer D. Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 34-35.

8 “The Draft Board Wants to See You,” Oregon Secretary of State Bev Clarno, accessed August 13, 2019, https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/exhibits/ww1/Pages/home-front-draft-board.aspx.

9 United States, Office of the Provost Marshal General, Selective Service Regulations: Prescribed by the President Under the Authority Vested In Him by the Terms of the Selective Service Law (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1917), 26-27, 67-68.

10 “U.S., Lists of Men Ordered to Report to Local Board for Military Duty, 1917–1918,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed March 25, 2019), entry for Ben Davis.

11 Keene, World War I, 93-95.

12 Theodore Kornweibel, Investigate Everything: Federal Efforts to Compel Black Loyalty During World War I (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2002), 77.

13 Office of the Provost Marshal General, Selective Service Regulations, 128.

14 The Selective Service System established five classifications: Class I for men eligible for immediate service, Class II, III and IV for temporary deferred married men with economic dependents and skilled industry workers, and Class V for those physically or mentally unfit for service. Keene, World War I, 36; Kornweibel, Investigate Everything, 78.

15 “U.S., Lists of Men Ordered to Report to Local Board for Military Duty, 1917–1918,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed March 25, 2019), entry for Ben Davis, August 4, 1918.

16 Michael S. Neiberg, The World War I Reader: Primary and Secondary Sources (New York: New York University Press, 2007), 274.

17 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Ben Davis; Robert J. Dalessandro, Gerald Torrence, Michael G. Knapp, Willing Patriots: Men of Color in the First World War (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Military History 2009), 153, 157.

18 Nick McGrath, “Fort Devens Massachusetts,” On Point 20, no. 4 (2015): 44, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26365430.

19 Dalessandro, Torrence, Knapp, Willing Patriots, 157.

20 McGrath, “Fort Devens Massachusetts,” 45; Carol R. Byerly, "The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919." Public Health Reports 125, no. Suppl. 3 (2010), 86, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2862337/

21 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Ben Davis; Dalessandro, Torrence, Knapp, Willing Patriots, 153.

22 Keene, World War I, 95.

23 Chad L. Williams, Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 108-109.

24 Keene, World War I, 95; Derrel B. Depasse, Traveling the Rainbow: The Life and Art of Joseph E. Yoakum (New York/Jackson, MS: Museum of American Folk Art/University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 11.

25 Ben Davis; Dalessandro, Torrence, Knapp, Willing Patriots, 153; McGrath, “Fort Devens Massachusetts,” 45.

26 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Ben Davis.

27 “Florida, State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed March 25, 2019), entry for Ben Davis, Pinellas County, FL 1935; “Florida, State Census,” Ancestry.com, Ben Davis, 1945.

28 "Florida Marriages, 1830-1993," database, FamilySearch.org (https://familysearch.org: accessed July 30, 2019), entry for Ben Davis and Annie R. Leach.

29 “Florida, State Census,” Ancestry.com, Ben Davis, 1945.

30 “Davis, Ben,” National Cemetery Administration, accessed August 7, 2019, https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/index.html?cemetery=N830.

© 2019, University of Central Florida