Charles “Carlo” Leonetti (January 9, 1895–June 3, 1994)

By E’ Monique Williams and Rachel Street

Early Life

Charles “Carlo” Leonetti was born on January 9, 1895 in Naples, Italy. Although we know little about Leonetti’s childhood in Italy, he became a prominent figure in New York society and left his mark in the art world. Around 1910, Leonetti moved to New York during the great waves of Italian immigration in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Emigrating from Naples as a teenager, Leonetti most likely left Italy due to displacements following the strains caused by the unification of Northern and Southern Italy in 1871.1 A number of other factors may have contributed to the mass emigration. Following a series of economic crises in Europe, the new unified government sought to increase revenue by expanding taxes on items like wheat and salt, both necessities of daily life. Naples’ agricultural economy was one of Italy’s hardest hit areas.2 Late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Italy also suffered because of a number of natural disasters and malaria outbreaks.3 Finally, Leonetti and his family likely witnessed the 1906 eruptions of Mount Vesuvius, which coated their city in ash and caused major devastation to neighboring cities like San Giuseppe and Somma. The eruption and its aftermath even forced the 1908 Summer Olympics to relocate to London.4 Any number of these factors may have pushed Leonetti’s departure from Italy.

Between 1901 and 1910, the number of those arriving in the US from Italy rose to over two million, which represented a large portion of the nearly nine million people who immigrated to the US during the decade.5 Following his arrival, Leonetti entered the New York art scene, drifting between multiple niches in the field. He pursued studies at the Cooper Institute in New York City from 1910-1914.6 The school provided free educational opportunities for the poor and working class who could take courses in engineering, art, architecture, humanities, and social sciences.7 He joined the Art Students League in 1913, which allowed students to work with well known artists and pursue their craft with little constraint.8 While there, Robert Henri, an artist who deviated from traditional academic art and stressed connecting art with life, served as Leonetti’s mentor.9

Military Service

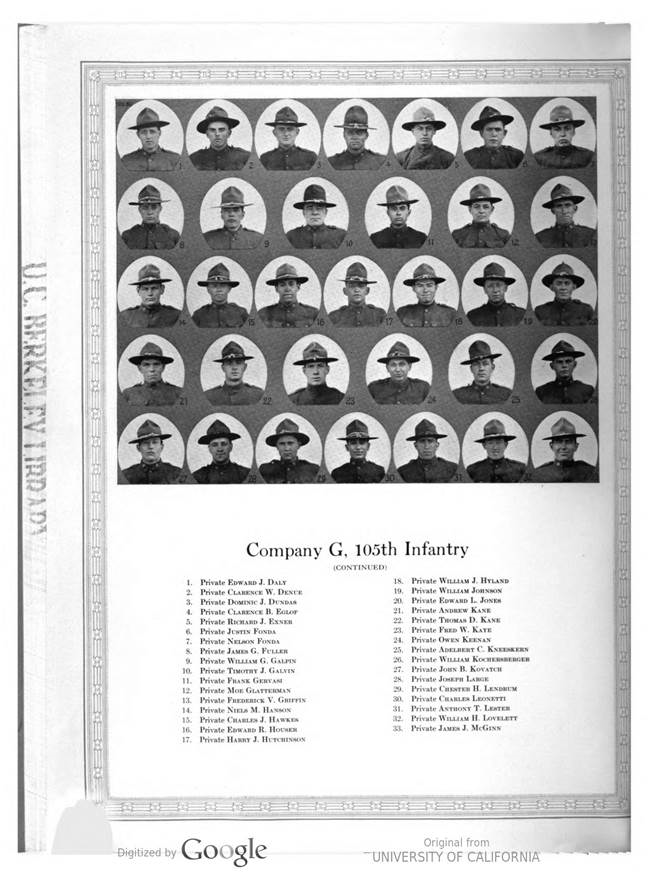

Leonetti enlisted in the army on July 26, 1917 and served in Company G of the 105th Infantry Regiment during World War I.10 He is pictured here in uniform while serving with Company G, 105th Infantry. While with the company, he likely fought in Flanders and Ypres. During the war, he fought in the trenches in Flanders and at Ypres as a private.11 At the Ypres offensive, the 105th Regiment—part of the 53rd Brigade of the 27th Division—fought German troops in the Dickebusch/Scherpenberg area in an effort to push the enemy troops back from the area and regain control of the Amiens-Paris Railroad, a mechanism for communication between the Allied troops.12 While in the regiment, Leonetti likely served as part of the Somme Offensive, specifically the effort to cross the Hindenburg Line and capture Bony and Bellicourt in France.13 These were critical battles in the final push to end the long and bloody “War to End all Wars”. While Leonetti served the US overseas, he retained his presence in the art world and gained notoriety from his covers of The Masses, a journal published in New York.14 Discharged from the army in April 1919, Leonetti continued officers’ training in the Army Reserve.15

Post-Service

After his return to the US, Leonetti became naturalized in May of 1920. It is likely that Leonetti benefited from legislation passed by Congress in 1918 that eased procedures for soldiers who served during the war and were honorably discharged.16 Almost 280,000 men who served our country also used the legislation to become citizens.17

Upon his return, Leonetti became a figure in the New York art scene. He participated in a variety of niches: photographing celebrities, painting, opening up a Greenwich Village-themed nightclub, translating “The Jest” (written by John Barrymore), acting in movies like Broken Blossoms, and dancing on Broadway.18 In his memoirs, Leonetti recounted that one night after a show he had a life changing moment: “I found a hundred dollar bill, and with it I bought the best camera I could find, and began taking photographs of the Broadway Stars—the Dennis-Shawn Dancers, Ted Shawn, Ruth St. Denis, Will Rogers, Three Black Crows, Anna Pavlova the Ballerina, May West, Marlina Detric [sic], Carnera, Jack Dempsey, etc.”19 His career path continued its upward trajectory after his appearance in Max Reinhardt’s play, "The Miracle", and his portrait of the lead actress, Lady Diana Manners. His experience helped Leonetti procure a position as an executive in the Macy’s photographic department where he worked long hours and encountered many more celebrities, including Eleanor Roosevelt, Nelson Eddy, and Harold Lloyd.20

After his stint with the department store, Leonetti returned to running his own photography business and obtained several advertising accounts with firms like Bratten, Barton, Durstine, and Osborne.21 During this period, Leonetti earned more money than at Macy’s, but suffered a financial loss of $2,000 when the stock market crashed in 1929.22 Leonetti, maybe nostalgically, remembered this loss as having had little impact on his career: “The loss affected me very little, as I was more interested in turning out works of art than making money. I refused to lower my prices. I preferred to quit business.”23 Colleagues admired his work but wondered how he could continue to charge between $100-$500 for a single print. He responded in his memoirs: “They thought ‘What a Profit!’ for a single print! But my photographs were ART! My photographs represented knowledge and experience. Actually I was rendering personal service and my work was more than well received.”24

Leonetti’s Return to Service

In July 1939, Leonetti married Mayme Laurel Sellers in Manhattan, New York.25 Two years later, as a Reserve Officer, Leonetti entered the service again in February 1941, shortly before Pearl Harbor and shortly after his forty-sixth birthday.26 After he rejoined the Army, Leonetti spent more time overseas in Germany after the Allied victory on May 8, 1945.27 Discharged in August 1946 after five years of service, Leonetti reentered civilian life with the “Soldier’s Medal for Bravery.”28 The Soldier’s Medal was awarded to “any person of the Armed Forces of the United States, or of a friendly foreign nation who while serving in any capacity with the Army of the United States, distinguished him/herself by heroism not involving actual conflict with an enemy.”29

That same year, he moved to Tampa with his wife, Mayme, where they maintained active involvement in the art community. 30 Sellers served as the director of the Tampa Art Institute, now the Tampa Museum of Art, and promoted the education of veterans at the institute after the creation of the GI Bill.31 After devoting much of his life to art and his country, Leonetti passed away on June 3, 1994 at ninety-nine years of age.32

Endnotes

1 Jordan Lancaster, In the Shadow of Vesuvius: A Cultural History of Naples (London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2005), 217-218.

2 Stephen Puleo, 22.

3 Ibid, 23.

4 William Herbert Hobbs, “The Grand Eruption of Vesuvius in 1906,” The Journal of Geology 14, no. 7, (1906): 640-642, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30078588.

5 Frank J. Cavoli, “Patterns of Italian Immigration to the United States,” The Catholic Social Science Review 13 (2008): 214.

6 "Carlo Leonetti,” Broadway Photographs, accessed April 19, 2017, http://broadway.cas.sc.edu/content/carlo-leonetti.

7 “History,” The Cooper Union, accessed June 15, 2017, https://cooper.edu/about/history.

8 “Leonetti Memoirs: the 1910s & 1920s,” Broadway Photographs,” accessed April 19, 2007, http://broadway.cas.sc.edu/content/leonetti-memoirs-1910s-1920s; “A Legendary Community of Artists,” The Art Students League of New York, accessed June 15, 2017, https://www.theartstudentsleague.org/about/legendary-community-artists/.

9 “Robert Henri,” Smithsonian American Art Museum Renwick Gallery, accessed June 15, 2017, http://americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artist/?id=2171; "Carlo Leonetti,” Broadway Photographs.

10 “WWI New York Army Cards,” database, fold3.com (https://fold3.com/ : accessed April 19, 2017), entry for Charles Leonetti, Army Serial Number 1204685.

11 "Carlo Leonetti,” Broadway Photographs.

12 “105th Infantry Regiment World War I,” New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, accessed June 15, 2017, https://dmna.ny.gov/historic/reghist/wwi/infantry/105thInf/105thInfMain.htm.

13 “U.S. Army Campaigns: World War I,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, accessed June 15, 2017, http://www.history.army.mil/html/reference/army_flag/wwi.html.

14 "Carlo Leonetti,” Broadway Photographs.

15 Ibid.

16 Jennifer D. Keene, “World War One: The American Soldier Experience” (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 106-107.

17 Ibid.

18 "Carlo Leonetti,” Broadway Photographs.

19 “Leonetti Memoirs: the 1910s & 1920s,” Broadway Photographs.

20 “Leonetti Memoirs: the 1910s & 1920s,” Broadway Photographs.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 “New York, Marriage Indexes, 1907-1995,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com/ : accessed April 19, 2017), entry for Charles Leonetti, Certificate Number 10510.

26 “U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010,” database, Fold3.com (https://fold3.com/ : accessed April 19, 2017), entry for Charles Leonetti.

27 "Carlo Leonetti,” Broadway Photographs.

28 “U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010.” ; “Hillsborough Obituaries,” Tampa Bay Times, June 5, 1994, page 11B, Newspapers.com.

29 “U.S. Army Service Campaign Medals and Foreign Award Medals,” U.S. Veteran Medals, accessed July 18, 2017, http://www.veteranmedals.army.mil/awardg&d.nsf/Medal%20Home?OpenFrameSet&Frame=Medal%20Home&Src=%2Fawardg%26d.nsf%2Fopener!OpenPage%26AutoFramed.

30 “Hillsborough Obituaries,” Tampa Bay Times.

31 Mark Ormond, “Tampa Art Institute/Tampa Bay Art Center/Tampa Museum of Art,” Modern Art in Florida, 1948-1970 (Tampa: Tampa Museum of Art, 2003).

32 National Cemetery Administration, "Charles Leonetti," US Department of Veterans Affairs, accessed July 18, 2017, https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/NGLMap?ID=5147803; “Hillsborough Obituaries,” Tampa Bay Times.

© 2017, University of Central Florida