Everett Alfred Farrar (September 19, 1920–May 20, 1996)

Neva B. Smith Farrar (November 4, 1921–January 7, 1999)

By: Zacharias Forsythe

Early Life: The Depression in Missouri

When Everett Alfred Farrar was born on September 19, 1920, in St. Louis, Missouri, his mother, Charlotte, was 23 and his father, Everett, was 31. 1 By age 10, Everett learned to read and write and had attended a significant portion of his early schooling in St. Louis, continuing on to complete high school by age 19 in 1940. 2 During Everett’s formative years, St. Louis experienced above average unemployment with nearly thirty-percent of the St. Louis population of 800,000 unemployed, according to to the the Bureau of Labor Statistics. 3 Despite these poor job prospects, Everett worked as a grocery store clerk in St. Louis before his enlistment, living with his parents during the hard economic times of the Great Depression. 4

Military Life: Seabees and the Pacific

Farrar enlisted in the United States Navy on December 5, 1942 in St. Louis, Missouri. 5 The Navy assigned him to the 62nd Naval Construction Battalion (CB), or the Seabees. Assigned to Company C, as seen here, Farrar engaged in work of the “utmost importance,” this being the repairs of the submarine facility on Oahu in March 1943. Additionally, the 62nd Seabees aided in the construction of new naval infrastructure on Oahu, such as communication network cabling, water systems, dykes, and pontoon assembly. After nineteen months on Oahu, in October 1944, the 62nd transferred to Maui to await the Iwo Jima invasion. 6

The 62nd, including Farrar, embarked for Iwo Jima in mid-January 1945; he was a passenger on the USS Starr on January 11, 1945. 7 The 62nd arrived on February 19, Iwo Jima’s D-Day. The 62nd’s sailor were split across three different ships on D-Day, waiting for their time to land on the beaches after the initial invasion. Farrar likely experienced the terrifying Kamikaze pilots that plagued the stationary ships during the amphibious landings. According to the battalion history, they endured five days of airborne harassment from Japanese forces. On February 24, the first detachment of the 62nd landed at Green Beach as they waited for the battle to stop so they could begin their assignments. 8

Farrar and the 62nd Seabees began work on Number One Airfield as soon as the battle ceased, well before the area designated for the airfield had been secured by the Marines. The 62nd fought off banzai attacks, hid from Japanese snipers, and took cover from enemy mortar fire as they worked through the night. The first aircraft to land at the airfield was a crippled B-29 Superfortress returning home from a bombing mission over Tokyo. 9 After completing their work at Airfield Number One, Farrar and the 62nd began work on Camp Bola, named after one of their fallen comrades, and Airfield Number Two. Each of these locations expanded the capacity of aircraft and personnel at Iwo Jima, facilitating the vital Island Hopping campaigns towards the end of World War II. Moreover, Iwo Jima acted as one of the ultimate goals for the campaign, as it placed Allied bombers within range of Tokyo and other major production centers in Japan. Records show that 1,191 fighter escorts and 3,081 strike sorties departed from Iwo Jima against Japan after the capture of the island, demonstrating its vital role in the Pacific war. 10

After Service: Boom in Florida

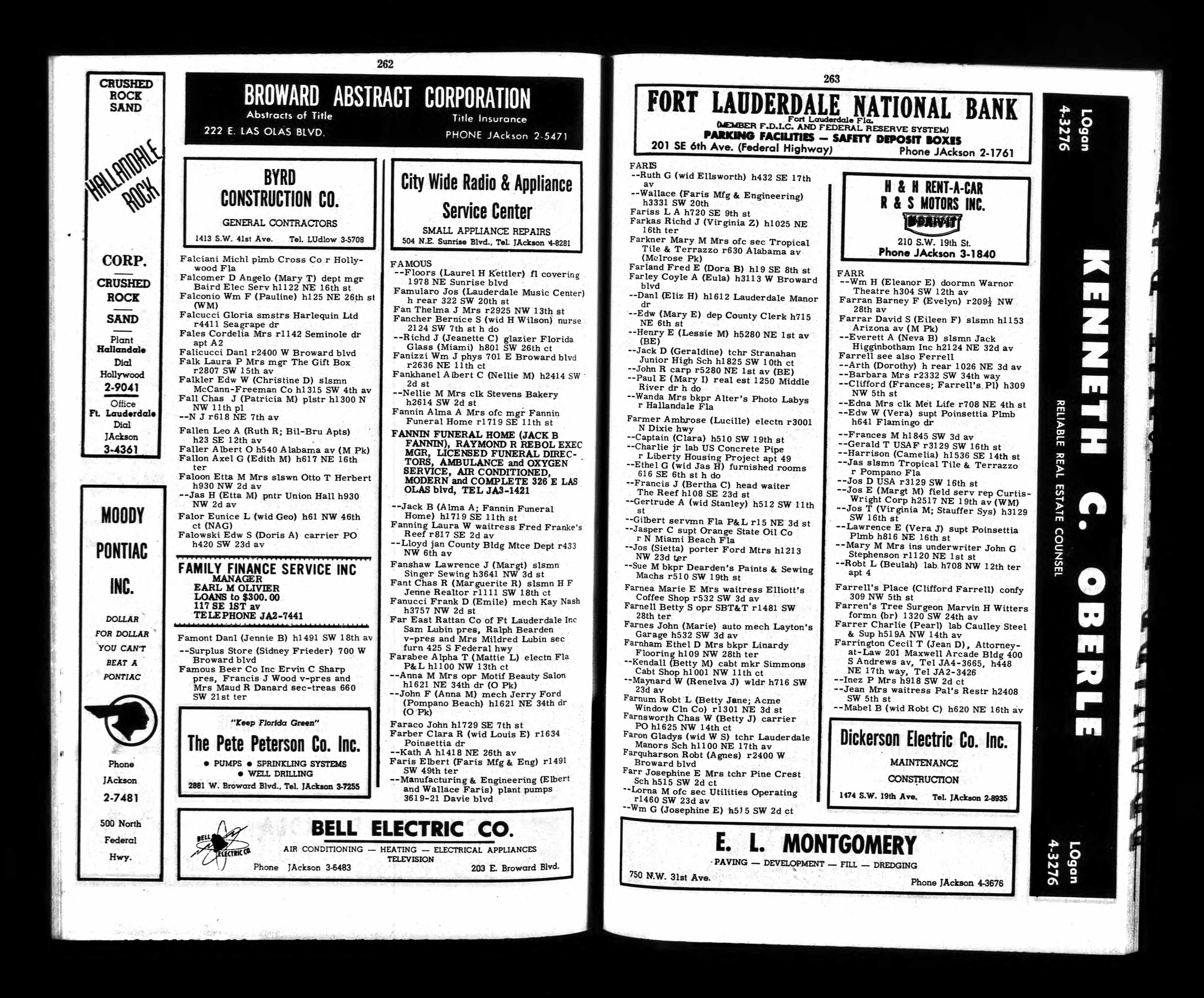

Farrar returned home after spending Victory-over Japan (VJ) Day on Iwo Jima. His service ended on December 17, 1945, as a Construction Mechanic Petty Officer 2nd Class. Before his official discharge from the Navy, Farrar met and later married Neva B. Smith on October 7, 1945 in Fulton, Arkansas. 11 Farrar likely moved to Florida in the early 1950s with his new wife and became a salesman or realtor for Jack Higginbottom Inc., a Fort Lauderdale-based realtor office, as noted in the city directory. 12 Farrar likely understood the boom occurring in the mid-twentieth century, impacting his decision to move and work here. From 1940 to 1960, Florida saw growth from two and a half million to nearly seven million residents. 13 This growth improved Florida’s economy including the real estate industry.

Everett Farrar passed away on May 20, 1996 in Port Richey, FL. His family later memorialized him at the Florida National Cemetery in Bushnell, FL on July 8, 1996. He is memorialized with his wife Neva, who passed on January 9, 1999 at Section MD Site 22. 14

Endnotes

1 “U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 14, 2017), entry for Everett Farrar.

2 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 14, 2017), entry for Everett Farrar, ED 96-148, St, Louis, St. Louis, Missouri.; “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 14, 2017), entry for Everett Farrar, ED 96-625, St, Louis, St. Louis City, Missouri.

3 James Neal Primm, Lion of the Valley: St. Louis, Missouri, 1746-1980 (Missouri History Museum, 1998), 441.

4 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed August 14, 2017), entry for Everett A Farrar, ED 96-625, St. Louis, Missouri, 16.

5 “U.S. Veterans' Gravesites, ca.1775-2006,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 14, 2017), entry for Everett A. Farrar.; “U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 14, 2017),), entry for Everett Farrar.

6 Sixty Seconds: CB Minute-Men (U.S. Navy Seabee Museum), online, Google Books (books.google.com : accessed July 15, 2017), pearl harbor.

7 “U.S. World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 14, 2017), entry for Everett A. Farrar.

8 Sixty Seconds: CB Minute-Men (U.S. Navy Seabee Museum), online, Google Books (books.google.com : accessed July 15, 2017), 121-123.

9 Sixty Seconds: CB Minute-Men (U.S. Navy Seabee Museum), online, Google Books (books.google.com : accessed July 15, 2017), 138.

10 Robert J. Moskin, The U.S. Marine Corps Story (Little: Brown and Company, 1992), 373.

11 “Arkansas, County Marriages Index, 1837-1957,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 14, 2017), entry for Everett A. Farrar.

12 “U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 14, 2017), entry for Everett A. Farrar, Fort Lauderdale, FL, 1956.; “Buy Homes - Stop Inflation” Fort Lauderdale News (Fort Lauderdale, FL) September 7, 1957.

13 Stanley K. Smith, “Florida Population Growth: Past, Present and Future” Bureau of Economic and Business Research, online, (bebr.ufl.edu : accessed July 20, 2017), 22.

14 National Cemetery Administration, "Everett A. Farrar," US Department of Veterans Affairs, accessed July 14, 2017, https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/NGLMap?ID=5955035

© 2017, University of Central Florida