Tellef Lindland (November 24, 1887–September 26, 1918)

By Eric Thompson

Early Life

On November 24, 1887, Eivind and Kari Lindland welcomed a son Tellef Lindland, in Norway.1 The Lindland family suffered several tragedies before and after Tellef’s birth. Tellef’s father Eivind experienced the loss of his three children and his first wife Siri. After marrying Tellef’s mother Kari in 1883, the couple had six children.2 Unfortunately, only Tellef, pictured here, and his older brother John reached the age of twenty, as Tellef’s other siblings died in infancy or in their teens.3 Tellef’s mother Kari passed away in 1893 and his father later married Kari’s younger sister Marte; they had additional children together.4

The Lindland family worked in agriculture, a common occupation for rural Norwegians. Yet, overpopulation in Norway, which caused land shortages especially after 1865, and the traditional division of land among the father’s heirs after his death meant Tellef had little hope of inheriting much land from his father. Additionally, young men faced bleak employment opportunities, especially after the 1880s, leading many to seek new beginnings elsewhere.5 Between 1825 and 1915, three major waves of Norwegians immigrated to the US due to widespread crop failures, land shortages, and the lack of employment opportunities. While family emigration largely marked the smaller first wave, individual departures of younger Norwegians, especially men, constituted much of the latter two waves of emigration.6

Norwegians like Tellef learned about America, particularly the Midwest, from territorial immigration commissions, land companies, newspapers, and personal correspondences with family and friends in America. Tellef’s older brother John immigrated to the US in 1905, eventually settling in Litchfield, North Dakota. In 1900, North Dakota held the highest percentage of Norwegians by state in the US at the time.7 Motivated by the bleak conditions in Norway and having a family member in America already, Tellef immigrated to the US via Canada in 1906. Tellef sailed aboard the RMS Virginian from Liverpool, England arriving in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, on August 24 and eventually moving in with his brother in North Dakota.8 Tellef and John were among the 214,000 Norwegians that migrated to the US during the third wave, between 1900 and 1914.9

Lindland eventually found his way to Brevard County, Florida.10 After the Civil War, Florida faced problems with a scarcity of labor as African Americans moved away from white farms and plantations. Additionally, since prejudiced whites viewed the remaining black labor as inadequate in quantity and quality, many whites saw foreign immigration, particularly white Europeans with knowledge of farming, as the solution. Thus, when Florida state agencies, county and local governments, and special interests groups like railroad and real estate companies advertised across the country, immigrants came to Florida in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.11 By the turn of the century, southern Brevard County contained a fairly large European immigrant population that worked in its farming communities.12

Lindland may have come to Brevard County through the Florida Indian River Catholic Colony. The land company, based in North Dakota, owned 40,000 acres of land in Tillman and Malabar, Florida and sought to bring Catholic immigrants from the Midwest to Florida. The company placed advertisements in ethnic newspapers across the Midwest with promises of fertile cropland in a tropical paradise.13 Instead, settlers, who began coming in mid-1912, faced land with sandy soil unsuitable for growing sustainable crops, a plague of mosquitoes, and unexpected freezes which destroyed crops meant for northern markets. By 1916, most of the families that came to the area left and those who remained adapted their careers to fishing and laboring, having exhausted their savings when relocating to Florida.14 While Lindland maintained his residence in Titusville, he likely relocated to Live Oak, Florida for greater opportunities than perhaps he could find in Brevard County by 1917.15

Military Service

After the US entry into World War I in April of 1917, as millions of native-born Americans volunteered and served in the military, foreign-born men also joined the war effort ultimately making up nearly one-fifth of the wartime army. The Selective Service Act in May of 1917 allowed draft boards to conscript immigrants from non-enemy countries into service, as well as second-generation Germans or first-generation Germans already serving in the US military before the war began.16 While Norway remained neutral in the conflict, proximity to Britain and strained relations with Germany meant that Britain saw Norway as a “neutral ally,” a term coined by Norwegian historian Olav Riste. Many immigrants also saw service in the military as a path to American citizenship, likely a motivating factor for Lindland.17 On May 21, 1917, Lindland enlisted in the Army at Fort Screven, Georgia, near Savannah.18

After his enlistment, the Army assigned Lindland to the 3rd Field Artillery Regiment Supply Company. Tellef enlisted as a Private before receiving a promotion to Wagoner and later Saddler on March 4, 1918. Before the widespread use of motorized vehicles in warfare, wagoners and saddlers relied on horses and mules to transport and sustain the Army. For Lindland, this would have involved hauling ammunition and other supplies to the field artillery battalions of the Sixth Division. Wagoners’ main responsibilities involved ensuring the maintenance of their equipment including the wagon and harness along with the care and safety of the horses and mules. Saddlers’ primary responsibilities involved repairing the harness and other leather equipment on horses.19

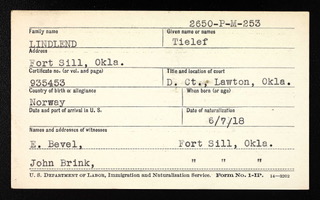

On April 4, 1918, the Army sent the 6th Field Artillery Brigade of the Sixth Division, which included Lindland’s 3rd Field Artillery, to Camp Doniphan, adjacent to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, for ten weeks of training at the Artillery Training Center.20 While Lindland was stationed at Fort Sill in May 1918, Congress passed an act which allowed foreigners currently serving in the US military to petition for naturalization without making a declaration of intent or proving five years of residence in the United States. Between May 9, 1918, and June 30, 1919, over 192,000 foreign-born US soldiers became naturalized American citizens, with Lindland, as shown here, becoming a citizen on June 7, 1918.21 After training, Lindland and the 6th Field Artillery Regiment embarked from the Port of New York on July 14, 1918, and headed overseas aboard the USS Caronia. Lindland left Nels Johnson, a friend from Live Oak, as his emergency contact. After short stops in Southampton and Liverpool, England on July 19 and 26 respectively, the unit arrived in France.22

After arriving in France on July 29, the Army detached Lindland and the 6th Field Artillery from the Sixth Division for additional training in the town of Valdahon, in eastern France near the Swiss border. The rest of the division, minus the artillery units, fought in the mountainous Gérardmer Sector further north of Valdahon beginning in late August of 1918. In one incident on October 4, over 300 Germans equipped with flamethrowers and machine guns attacked about sixty men of the Sixth Division, but the Americans managed to repel the attack and even captured five German prisoners. By October 12, the Sixth Division occupied the Gérardmer Sector.23

Lindland, however, did not get to celebrate the successes of his division at Gérardmer. During training, Lindland, like millions of people around the world, fell ill in the growing influenza pandemic of 1918 and 1919. In the midst of the war and after, the transport of troops and goods, along with the conditions soldiers and civilians faced, allowed the deadly virus to spread. The disease sickened at least a quarter of the world’s population and roughly a million US soldiers fell ill. While many recovered, Lindland, and others like him, developed secondary complications like pneumonia. Once soldiers contracted pneumonia, only half of them recovered.24 Pneumonia moved incredibly swiftly, with one army physician stating “it is only a matter of a few hours until death comes, and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate.”25 Lindland died from lobar pneumonia on September 26, 1918, with the Army notifying his friend Nels Johnson of his death.26

Legacy

Tellef Lindland’s story is quintessentially an American story. His story entails an immigrant seeking greater opportunities by leaving his home country, facing challenges and hardships in a frontier community, and volunteering to serve his adopted home during World War I. In recent years, Brevard Community College (BCC) launched the Brevard County War Dead project to memorialize servicemen and women with connections to Brevard County from World War I to the present; Tellef is remembered on the group’s website.27 Lindland is buried in Plot A, Row 11, Grave 13 at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial in France.28

Endnotes

1 “Public Member Stories, Birth and Baptism,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 11, 2018), entry for Tellef Eivindsen Lindland, https://urn.digitalarkivet.no/URN:NBN:no-a1450-kb20070105620213.jpg.

2 “Maureen Smischney Family Tree,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 18, 2018), entry for Eivind Johnsen Lindland, Facts; “Norway, Select Marriages, 1660-1926,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 18, 2018), entry for Eivind Johnsen.

3 The picture of Tellef Lindland comes, with permission, from the family tree of Maureen Smischney, his second cousin. We would like to thank Maureen Smischney for all the help she has provided.a “Maureen Smischney Family Tree,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 18, 2018), entry for Tellef Eivindsen Lindland, Facts; “Public Member Photos & Scanned Documents,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 19, 2018, entry for Tellef Lindland.

4 “Norway, Select Burials, 1666-1927,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 18, 2018), entry for Kari Tellefsdatter; “Maureen Smischney Family Tree,” Ancestry.com, Eivind Johnsen Lindland, Facts; “Maureen Smischney Family Tree,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 18, 2018), entry for Kari Tellefsdatter Egdalen, Facts.

5 Correspondence between Maureen Smischney (second cousin of Tellef Lindland) and Eric Thompson, March 2018; Samuel Laing, Journal of a Residence in Norway During the Years 1834, 1835, & 1836 (London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1862), 143; Odd S. Lovoll, The Promise of America: A History of the Norwegian-American People (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984), 23, 26-29.

6 The three major waves of Norwegian migration are 1825 to 1865, 1865 to 1900, and 1900 to 1915. Lovoll, The Promise of America, 14, 16, 23, 29.

7 Odd S. Lovoll, Across the Deep Blue Sea: The Saga of Early Norwegian Immigrants (St. Paul, MN: The Minnesota Historical Society, 2015), 172; “1920 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http;//www.ancestry.com : accessed March 28, 2018), entry for John Lindland, Jamestown Ward 1, North Dakota.

8 “Canadian Passenger Lists, 1865-1935,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 13, 2018), entry for Tellef Lindland; U.S., Border Crossings from Canada to U.S., 1895-1960,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 13, 2018), entry for Tellef Lindland.

9 Lovoll, The Promise of America, 29.

10 “WWI Service Cards,” database, FloridaMemory.com (https://www.floridamemory.com : accessed July 16, 2018), entry for Tellef Lindland.

11 George E. Pozzetta, “Foreigners in Florida: A Study of Immigration Promotion, 1865-1910,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 53, no. 2 (October 1974), 165-168, https://www.jstor.org/stable/30149799; “Tellef Lindland,” FloridaMemory.com (https://www.floridamemory.com: accessed July 11, 2018).

12 Nancy Yasecko, interview by Norris Andrews, Brevard County Historical Commission Oral History Video Project, Brevard County Historical Commission, January 16, 1994.

13 “Fruit & Truck Farms on the East Coast of Florida in the Famous Indian River District,” in A Booklet of Conservative Facts and Figures about Florida (Chicago, 1912), 3-4.

14 Built in 1914, St. Joseph’s Catholic Church served the new settlers of Tillman along with other residents of Brevard County. In 1987, the church submitted an application for registry into the National Register of Historic Places, including the historical significance of the church to Brevard County including the Florida Indian River Catholic Colony. See United States Department of Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form: St. Joseph's Catholic Church, December 2, 1987, accessed July 16, 2018, 4, 6, https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/79290839-3333-4b55-b786-cc12b3cbb6b2; Georgiana Greene Kjerulff, Tales of Old Brevard (Melbourne, FL: Kellersberger Fund of the South

Brevard Historical Society, Inc., 1990), 67.

15 Lindland’s WWI Service Card lists his residence in Titusville, but local newspapers marking Lindland’s death along with other Florida casualties from World War I list Live Oak as his residence. Additionally, his emergency contact Nels Johnson was a resident of Live Oak. “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Tellef Lindland;

“The American Casualty List,” Tampa Tribune (Tampa, FL), November 10, 1918; “American Soldiers of World War I,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 27, 2018), entry for Tellef Lindland.

16 Jennifer D. Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 105-108.

17 The direct quote aboves comes from the edited collection of Gearóid Barry, Enrico Dal Lago, and Róisín Healy (eds.), Small Nations and Colonial Peripheries in World War I (Boston: Brill, 2016), 97; Keene, World War I, 106-107.

18 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Tellef Lindland.

19 Debbie M. Lies, Images of America: Will Rogers Coliseum (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2012), 13; War Department, Manual for Farriers, Horseshoers, Saddlers and Wagoners or Teamsters 1914 (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1915), 57-58, 68, 74-75, 78-80.

20 Army War College, Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War: American Expeditionary Forces, Divisions Vol. 2 (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1931), 93.

21 “Camp Doniphan at Fort Sill, Oklahoma,” Kansas Memory, accessed July 17, 2018, http://www.kansasmemory.org/item/219872; “Naturalization Records,” National Archives, accessed July 17, 2018, https://www.archives.gov/research/naturalization/naturalization.html; “Missouri, Western District Naturalization Index, 1840-1990,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed July 17, 2018) entry for Tielef Lindlend.

22 “US Army WWI Transport Service, Passenger Lists,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com : accessed July 17, 2018), entry for Teller sic Lindland; Army War College, Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces, 93.

23 Army War College, Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces, 91, 95; American Battle Monuments Commission, American Armies and Battlefields in Europe: A History, Guide and Reference Book (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1938), 422-423, 443.

24 Keene, World War I, 165-167.

25 Keene, World War I, 166.

26 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Tellef Lindland.

27 Lynn Pickett of Brevard Community College (BCC) inspired the Brevard County War Dead project. Jim and Bonnie Garmon researched and compiled data on veterans with ties to Brevard County. Additionally, in 1982, BCC established a Memorial Wall in the amphitheater with a list of the names of those who gave their lives for American freedom. The wall recognizes servicemen and women from World War I through the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Tellef Lindland is listed on the the webpage, but the website indicates he is not on the Memorial Wall. “Veterans Memorial Wall at Brevard Community College,” Brevard County War Dead, accessed July 11, 2018, https://sites.google.com/a/flbgs.org/brevard-county-war-dead/home; “World War I Casualties from Brevard County”, World War I- Brevard County War Dead, accessed July 11, 2018, https://sites.google.com/a/flbgs.org/brevard-county-war-dead/world-war-i.

28 “Tellef Lindland,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed July 11, 2018, https://www.abmc.gov/node/327443#.WuHUSYjwaUk.

© 2018, University of Central Florida