Edward C. De Saussure (March 13, 1891–October 14, 1918)

By Nikki Hearn and Marie Oury

Early Life

Edward Cantey De Saussure1 was born on March 13, 1891 in Atlanta, Georgia. His parents, George R. De Saussure and Sarah Cantey, married in 1888 and had four children, all born in Georgia: Mary R. (1888), Edward, Esther S. (1893), and Henry W. (1897). Edward’s father, George, worked as a bank examiner and owned the family’s home. Edward, nine years old at the time of the 1900 census, attended school along with two of his siblings.2

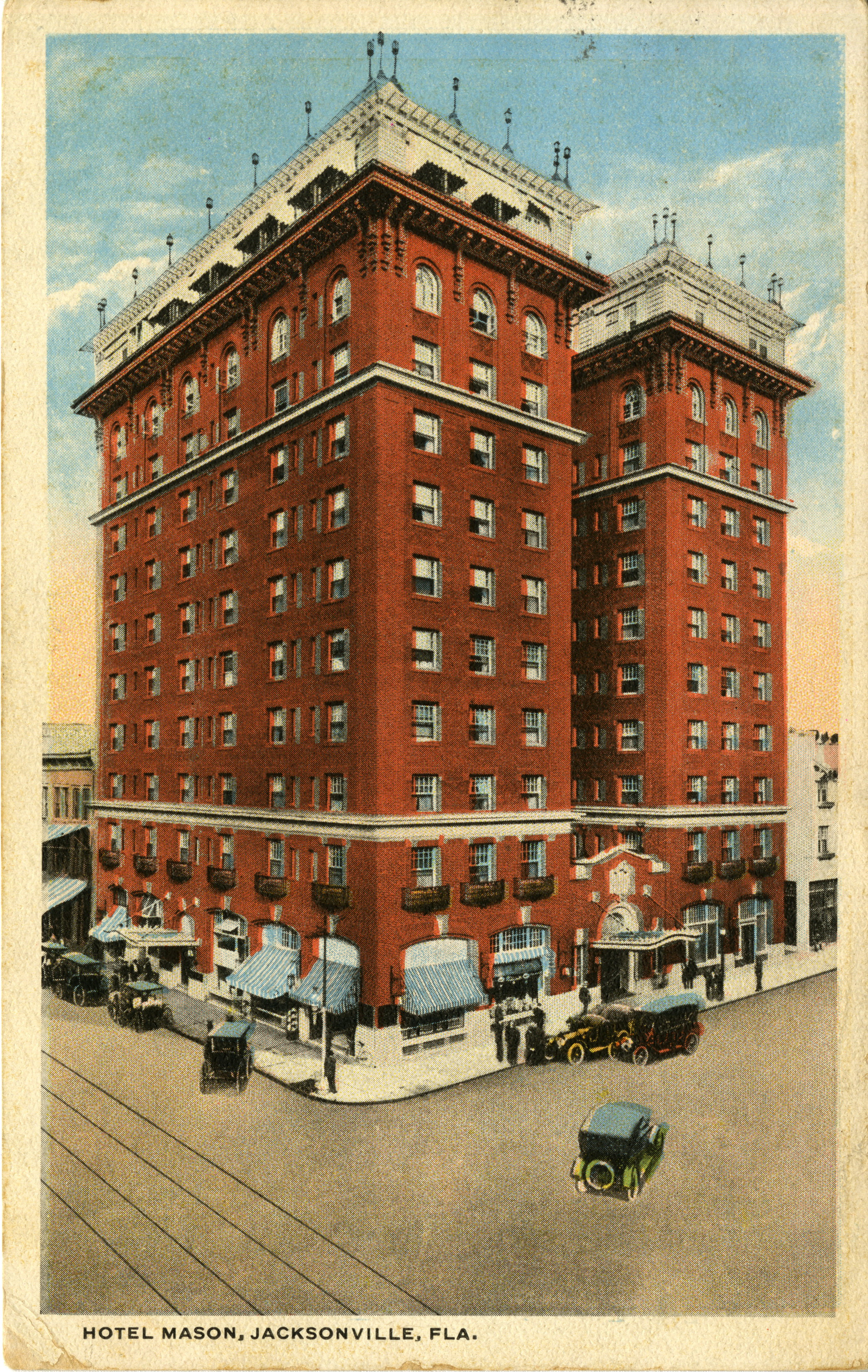

In late 1904 or early 1905, the family moved from Atlanta, Georgia, to Jacksonville, Florida, where Edward’s youngest brother, George, joined the family in 1906. In Jacksonville, Edward’s father continued to work in banking, first as a cashier; by 1909 he had become Vice President of the Barnett National Bank.3 In 1910, Edward, at the age of nineteen worked as a clerk in a naval store.4 By 1917, he worked as an auditor at the Mason Hotel.5

Military Service

On May 31, 1917, Edward De Saussure, then twenty-six, registered at Fort McPherson, GA to serve his country. Prior to joining the US Army, Edward De Saussure had at least two years of military experience with the Florida State Troops, where he earned the rank of Sergeant.6 In 1908, Edward De Saussure appeared in the Florida State Troops’ annual Report of the Adjutant General as a marksman and in 1910 as a “sharpshooter.”7 In 1917 and through the entire war, the US Army urgently needed to produce officers on a large scale. The Army did this by graduating West Point classes early, recalling retired officers, federalizing National Guard officers, and creating ninety-day officer training camps.8 Selected to participate in the ninety-day First Officers’ Training Camp at Fort McPherson, Edward received a commission as a Second Lieutenant on August 9, 1917.9

He then transferred to the newly created Camp Gordon, Georgia, where he was assigned to the 82nd Division, nicknamed the “All-American” Division because it had draftees from the forty-eight states. At Camp Gordon, the 82nd Division underwent training in European-style trench combat, as well as open warfare, using rifles and bayonets.10

On April 10, 1918, the All American Division moved toward the ports of embarkation in Boston, Brooklyn, and New York.11 Lieutenant De Saussure boarded the HMS Grampian, a British ship, in Boston, Massachusetts, on May 1, 1918, deployed with a machine gun company in the 328th Regiment, 82nd Division.12 The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) faced a shortage of ships to transport its troops to Europe, so General Pershing reached an agreement with the British to transport over one million American soldiers; as part of the agreement six American divisions completed their training with the British.13 The 82nd was one such division. They arrived at Liverpool, England, on May 16, 1918.14 From there, they passed through Southampton before crossing the Channel to Le Havre, France, and traveling by train to the British sector near Escarbotin for additional training with the British 66th Division. Three weeks into training with the British Army and getting used to the British weapons, orders came to leave all the weapons and to move the 82nd Division North of Toul, in an American sector.15

While the All American Division relieved the 26th US Division on the Woëvre front, known as the Lagny Sector, by June 25, 1918, Lieutenant De Saussure’s machine gun company attended an Automatic Arms School at Bois l’Eveque, between Toul and Nancy, for further training from French officers and joined the front line on July 5, 1918.16 The 82nd Division stayed on in this relatively calm sector until August 10, getting used to the trench life which included numerous patrols, a few artillery barrages, and “gazing” at the enemy line for hours.17

After a few day in the rear at Blénod-les-Toul, South of Toul, the All American Division relieved the 2nd Division in the Marbache Sector, north of Nancy.18 Possibly due to his experience and holding the rank of Second Lieutenant for approximately one year, De Saussure was promoted to First Lieutenant on August 16, 1918, the rank he held when he died.19

On September 12, 1918, the Marbache Sector merged into the St. Mihiel Operation during which the 82nd Division protected the First Army’s right flank.20 Lieutenant De Saussure’s regiment engaged in a series of offensives along the west bank of the Moselle River, with the objective for the regiment to keep contact with the enemy at all times.21 The All American Division suffered a thousand casualties, a reminder that fighting which supported the main action of a battle had deadly consequences because of long-range artillery and the other modern weapons used in World War I.22 The St. Mihiel Offensive, the first AEF led attack, originally intended to take the city of Metz, an important logistics center for the Germans to supply the Hindenburg defensive line. After three days, and under pressure from the French high command, the AEF cut short the offensive, after reducing the St. Mihiel Salient and taking the town of St. Mihiel, but without reaching Metz, in order to shift to Meuse Argonne Offensive. Marechal Ferdinand Foch, the French General and Supreme Allied Commander, had planned a united Allied offensive on the entire Western Front starting on September 26, 1918. Foch assigned the AEF to the difficult region of Meuse Argonne. The AEF successfully overcame numerous challenges including transferring men and material from the St. Mihiel region to the Meuse Argonne area in ten days, and keeping it secret from the Germans until the offensive began.23

The 82nd Division took part in this major transfer of troops, leaving the Marbache Sector on September 21, 1918 and arriving in the Argonne forest by September 25, 1918.24 Most of the All American division needed rest and replacement from the St. Mihiel attack and did not participate in the first days of combat. It was in reserve, under the First Army.

From October 3 to October 6, the 82nd Division advanced to the woods west of Varennes. This advance placed the all American Division in the sector of the 77th Division, another division also attached to the First Army. On October 3, nine companies of the 77th Division, over 500 men, broke through the enemy lines, but were quickly encircled. Trapped for five days, the “Lost Battalion” suffered heavy losses, a severe shortage of supplies, and incidents of friendly fire.25 Lieutenant De Saussure’s 328th Regiment, along with the 327th Regiment and the 28th Division, assisted in reestablishing contact with the remaining men of the 77th Division on October 8, 1918, suffering high casualty rates as they rescued the “Lost Battalion.”26

By the morning of the October 10, attacking from the east flank, the 328th Regiment, helped clear German units out the Argonne forest, and stopped the German artillery fire which had been hitting Allied units from the right edge of the forest.27 Later in the day, the 82nd Division began to move east across the Aire River in an attempt to take the Kriemhilde Stellung, a defensive outpost of the Hindenburg line. On October 12-13, the 328th Regiment was located in the vicinity of the villages of Fleville and Marcq, going north in the direction of St. Juvin and Sommerance. The terrain changed significantly from the Argonne forest; instead of thick woods, they faced plains bare of vegetation and rollings hills where the Germans set up defensive positions in a few deep ravines and isolated patches of trees.28

On October 14, the 328th Regiment, located on the St. Juvin-Sommerance Road, reached the St. Juvin-St. George Road about 500 yards south, and then continued pressing forward for just over a mile. The Regiment faced heavy artillery, rifle and machine gun fire as well as gas, generating substantial casualties.29

On October 14, 1918 Lieutenant De Saussure was wounded by shrapnel, possibly in the hand, while fighting just north of the Sommerance-St. Juvin Road. Evacuated from the front for treatment, he reportedly removed the tag marking him as wounded and returned to the front lines that same day to resume command of his company. Shortly after Lieutenant De Saussure rejoined his men, an exploding artillery shell killed him instantly.30 His parents were informed of his death on November 12, 1918, one day after the armistice went into effect.31

Legacy

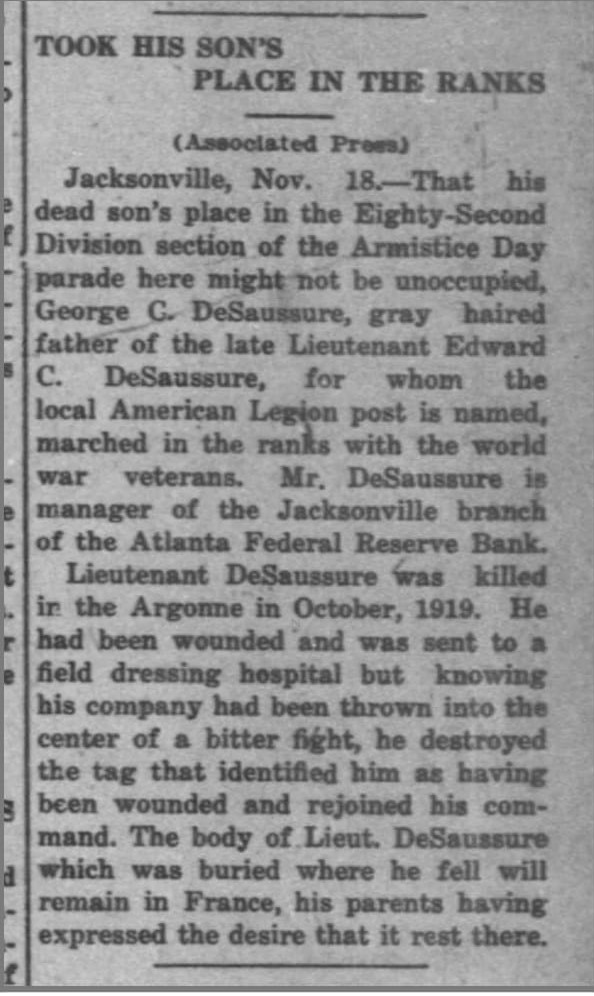

On June 12, 1919, Lieutenant De Saussure earned, posthumously, the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism.32 Within a year of his sacrifice, an American Legion Post in Jacksonville, FL bore his name. The new organization planned a parade, in 1919, to celebrate the first anniversary of Armistice Day.33 The Edward C. De Saussure American Legion Post #9 remains active today.34 In November 1921, during the Armistice Day Parade, Lieutenant De Saussure’s father, George R. De Saussure, marched with the 82nd Division to commemorate his fallen son. At least two newspapers in Florida, including the Ocala Evening Star, reported the event with an article, pictured here, entitled “Took His Son’s Place in the Ranks.”35

A memorial stone was dedicated, in 1933, at Camp Gordon, St. Juvin-St Georges Road, Georgia to the men of the 328th Infantry, 82nd Division. The stone was later moved to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, when it became the new home of the 82nd Airborne Division in 1960.36 Lieutenant De Saussure is buried in the Meuse-Argonne cemetery, in Plot B, Row 33, Grave 22 alongside 14,246 other American soldiers who fought and died in the Meuse-Argonne.37

Endnotes

1 The spelling of the last name “De Saussure” varies. In the sources used to document this biography, it can be found as “Desaussure,” “DeSaussure,” or “De Saussure.” We have decided to keep the two words version because it is the spelling used on the family members’ headstones. To see the spelling on De Saussure headstones go to https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/44265954/edward-cantey-desaussure.

2 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 20, 2018), entry for Edward Desaussure, Georgia.

3 Since arriving in Jacksonville, FL in 1905, George De Saussure worked for the Barnett National Bank which before 1903 had been known as the National Bank of Jacksonville. In the city directories from 1905 to 1909, George De Saussure was recorded as a cashier, then in 1910 he appeared as Vice President of the Barnett National Bank. “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 20, 2018), entry for George R. Desaussure, Florida; “U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995: Atlanta, Georgia, City Directory, 1904,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed June 26, 2018), entry for George Desaussure; “U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995: Jacksonville, Florida, City Directory, 1905,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed June 26, 2018), entry for George Desaussure.

4 A Naval store was part of the turpentine industry. From the end of the nineteenth century up to 1950, turpentine collection was a dominant industry in Florida as turpentine was exported all around the world to be used in medecin, cleaning products, and wooden boat coating. It is likely that Edward De Saussure worked as a clerk for one of Jacksonville turpentine companies. For more, see Bob Clarke, "Episode 23: Turpentine Industry," A History of Central Florida, Dr. Robert Cassanello, Progject Editor, podcast video, August 1, 2014, (http://stars.library.ucf.edu/ahistoryofcentralfloridapodcast/24/: accessed September 22, 2018).

5 “1910 United States Federal Census”, Ancestry.com, Edward Desaussure; “United States World War I Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 20, 2018), entry for Edward Desaussure, Jacksonville, Florida.

6 “United States World War I Registration Card,” database, Ancestry.com; Alison Simpson (Historian at the Florida National Guard, St Augustine, FL) correspondence with Marie Oury, June 2018. According to Ms. Simpson, “Florida State Troops reorganized as the Florida National Guard in 1909.” We are grateful for all the assistance Ms. Simpson provides UCF’s VLP.

7 Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Florida for the year 1908, 194. This record is part of Archives of the Florida National Guard, St. Francis Barracks, St. Augustine, FL and comes to us from Alison Simpson. Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Florida for the year 1910, (Tallahassee, FL: T.J. Appleyard, State Publisher, 1910-11), 254 (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112109613510;view=1up;seq=618: accessed September 28, 2018).

8 Edwin Kennedy Jr., “Mass-Producing Leaders: WWI Army Needed a Lot of Officers- Quickly,” Army Magazine 67, issue 7, (July 2017): 47-49 (https://www.ausa.org/articles/mass-producing-leaders-wwi: accessed September 27, 2018).

9 “Seventeen Tampans Get Commissions at Ft. M’Pherson School,” The Tampa Tribune, August 14,1917, Page 3, Newspapers.com.; “United States World War I Service Card,” database, Floridamemory.com (http://www.floridamemory.com, accessed March 20, 2018), entry for Edward Desaussure, Jacksonville, Florida.

10 Paul Stephen Hudson and Lora Pond Mirza, “Transforming the Atlanta Home Front: Camp Gordon During World War I,” Georgia Historical Quarterly Vol. 101 Issue 2. (2017): 147-165.

11 Order of the Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War, vol. 2 (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History United States Army, 1931), 349. To access PDFs of this seventeen volume set visit: https://history.army.mil/html/bookshelves/collect/oob_us_lf_wwi_1917-1919.html.

12 “U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com:accessed March 20, 2018), entry for Edward Desaussure, Boston, Massachusetts; Historical Committee (U.S), History of the Three Hundred and Twenty Eighth Regiment Infantry, Eighty Second Division, American Expeditionary Forces United States Army, (Atlanta, Georgia: Foote & Davies Co), 15.

13 Jennifer D. Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 124.

14 Historical Committee, History of the Three Hundred and Twenty Eighth Regiment Infantry, 17.

15 Divisional Officers, Official History of 82nd Division, American Expeditionary Forces, “All American” Division, 1917-1919 (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merril, 1919), 11-12.

16 Divisional Officers, Official History of 82nd Division, 13.

17Historical Committee, History of the Three Hundred and Twenty Eighth Regiment Infantry, 27.

18 Divisional Officers, Official History of 82nd Division, 17.

19 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Edward De Saussure.

20 Order of the battle of the United States land forces in the World War, vol 2, 353.

21 Divisional Officers, Official History of 82nd Division,19-21; Historical Committee, History of the Three Hundred and Twenty Eighth Regiment Infantry, 32-33.

22 Edward G. Lengel, To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918, the Epic Battle that Ended the First World War, (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, 2008), 265; Divisional Officers, Official History of 82nd Division, 17-29.

23 Richard Rubin, The Last of the Doughboys: The Forgotten Generation and their Forgotten World War, (New York, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2013), 323; Lengel, To Conquer Hell, 49-53.

24 Divisional Officers, Official History of 82nd Division, 28-30.

25 Alan D. Graff, Blood in the Argonne: The “Lost Battalion” of World War I (Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2005), 153-166.

26 Michael Clodfelter, The Lost Battalion and the Meuse-Argonne, 1918: America’s Deadliest Battle (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2007), 150-157.

27 Historical Committee, History of the Three Hundred and Twenty Eighth Regiment Infantry, 49.

28 Divisional Officers, Official History of 82nd Division, 85-86.

29 Historical Committee, History of the Three Hundred and Twenty Eighth Regiment Infantry, 53.

30 Divisional Officers, Official History of 82nd Division, 143.; “D.S.C. Awarded to Liuet De Saussure,” The Orlando Sentinel, (Orlando, Florida) June 15, 1919, 6, Newspapers.com.

31 “Lieut. Desaussure of Jacksonville is Killed in Action,” The Tampa Tribune, (Tampa, Florida) November 14, 1918, 2, Newspapers.com.

32 “Distinguished Service Cross,” The Tampa Tribune, (Tampa, Florida) June 13, 1919, 1, Newspapers.com.

33 “All States Celebrate,” Fort Scott Daily Tribune and Fort Scott Daily Monitor, (Fort Scott, Kansas) November 10, 1919, 1, Newspapers.com.

34 Department of Florida 5th district Official Website, American Legion 5th District, Northern Area Department of Florida, 2013-2018 (http://www.al5thdistrictfl.org/posts/post009-2013-4.htm: Accessed June 30, 2018); the Post uses Facebook as its official page: https://www.facebook.com/americanlegionpost9fl/.

35 “Took his Son’s Place in the Ranks,” The Ocala Evening Star (Ocala, Florida), November 19, 1921, 1, Newspapers.com. See also: “Marches for Dead Son,” Tampa Bay Times (St Petersburg, Florida), November 17, 1921, 7, Newspapers.com.

36 Commemorative Landscapes of North Carolina, “328th Infantry, 82nd Division, AEF Memorial, Fort Bragg” DocSouth (http://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/monument/393: accessed July 2, 2018).

37 E.C. Desaussure, “Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery,” American Battle Monuments Commission, May 6, 2011, (https://www.abmc.gov/node/328872#.Wzd-ndIzbZY: accessed June 30 2018).

© 2018, University of Central Florida