Will Todd (August 31,1892–April 8,1919)

By Nicholas Gottschalk and Matt Patsis

Early Life

Will Todd was born on August 31, 1892, in Moultrie, Georgia.1 When Will and his family lived there, Moultrie was a small agricultural town, where Will’s family likely worked in naval stores harvesting turpentine and other pine products, a substantial industry in Moultrie during the late nineteenth century. 2 At some point, Will and his family moved from Moultrie to Panama City, Florida.3 While we are not sure exactly when or why he moved, his family may have been in search of new or better opportunities working in naval stores.4 It seems that by the time Will was twenty-five, he acted as head of household, supporting his mother and sister, while working for a man named Walter Hobbs.5 Will worked as a laborer in Hobbs’ naval store, until at least 1917, when he registered for the draft.6 We also know that Will never married but, he may have had a girlfriend, Miss Mary Johnson, whom he listed as his emergency contact while in the military.7

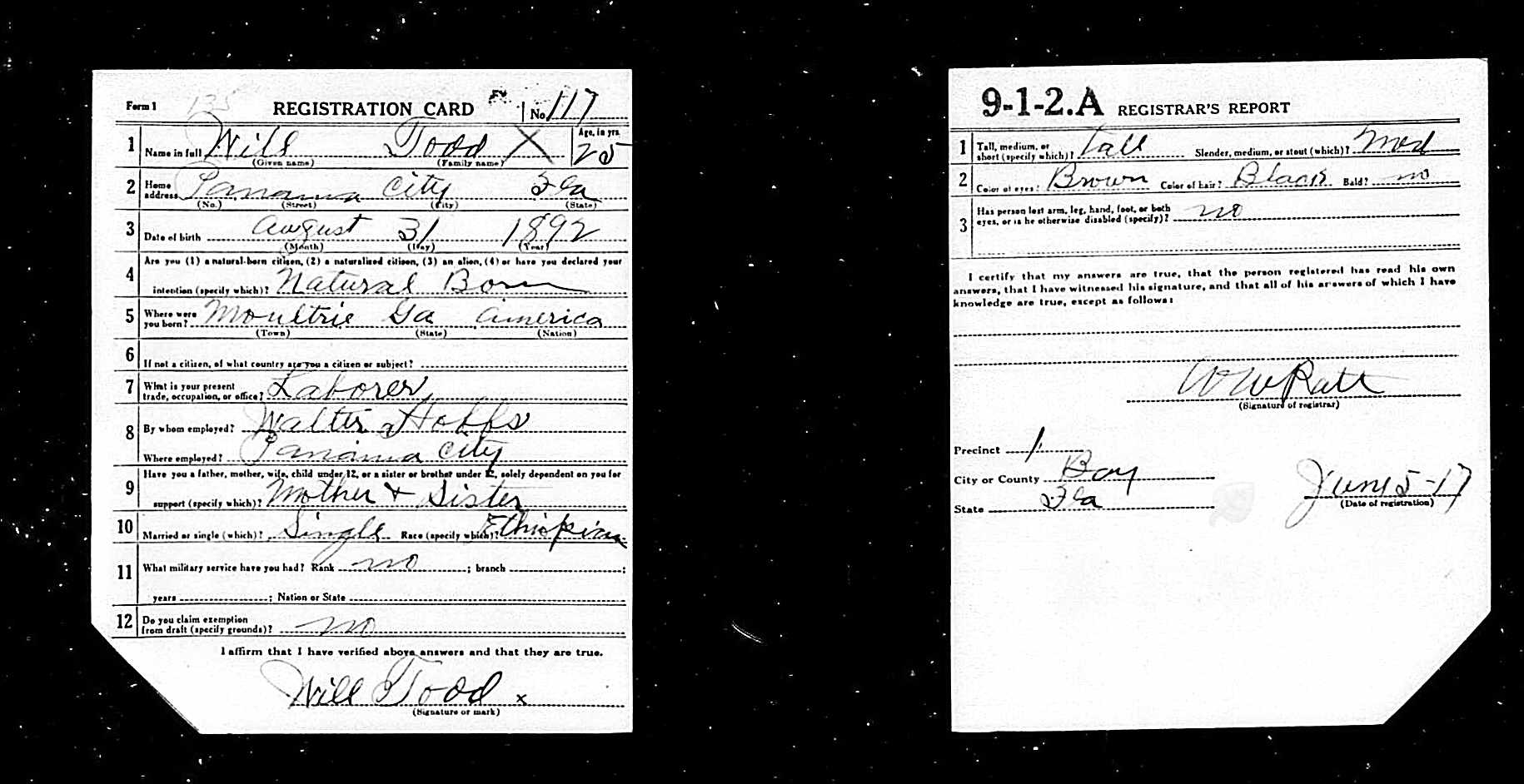

Growing up in the Jim Crow South, Will faced a form of racism that was ingrained in the structure of Southern society.8 While we have fewer documents to help us piece together Will’s life because of the history of structural racial discrimination, we can perhaps hear his voice and his pride in his identity in one significant place. Will’s military registration card, pictured here, lists him as Ethiopian, not colored, not negro. This one word perhaps tells us a great deal about Will’s refusal to allow the white dominated society to diminish his identity as an African American. Even though Will seems to have signed his registration with an “X”, implying that he, like so many others during this time, was illiterate, this unique instance of self-identification offers us a possible glimpse at the proud man that was Will Todd.

Military Service

In 1917, Will, like other men between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-one, filled out a mandatory American draft registration on June 5, 1917.9 On Aug 2, 1918, Will was inducted into the US Army, and was ordered to report to Camp Devens, in Ayer, Massachusetts, pictured here, to begin training.10 Todd was eventually assigned to the segregated 807th Pioneer Infantry as a Private.11 This unit, as with many segregated units in the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), was primarily a non-combatant unit that performed a wide range of duties in France during and immediately after World War I.12 African Americans were disproportionately assigned to noncombatant units during the First World War, since white Southerners feared that arming and training black men would lead to racial violence against whites after the war. Subsequently, African Americans were not well armed, received little combat training, and were relegated to less desirable tasks. Yet, despite institutional attempts to keep black men from serving in combat, many African Americans readily and proudly served their country with the hope of paving the way for recognition of their equality and advancement of their civil rights.13

After completing their training, Will Todd, along with the rest of the 807th Pioneer Infantry set sail for France aboard the USS Maui on September 4, 1918.14 By the time Will arrived in France later that September, the Allies were preparing for the final push to end the war, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. This final Allied assault began on September 26, 1918, and the 807th Pioneer Infantry was at some point sent into action under the command of the French army.15 It was not unusual for African American units to be assigned to the French Army, as many white American officers doubted the abilities of African Americans, and thus did not want them under their command.16

As a noncombatant unit, Todd and his comrades were responsible for bridge-building, destroying unexploded ordnances, and burying fallen soldiers, amongst other tasks.17 While the 807th was not a designated combat unit, they did see combat during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive on at least one occasion. One of Will’s comrades that survived the war described how the 807th Pioneers were attacked with poison gas, and engaged the German Army in trench warfare with bayonets.18 Despite the institutional racism that led to Will and many other African Americans serving under French command, the 807th Pioneer Infantry distinguished themselves, with several members earning the Croix de Guerre for their exemplary service during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.19

The Allies were victorious at the Meuse-Argonne which led to the armistice on November 11, 1918. Unfortunately, even though the fighting had stopped, soldiers were afflicted by rampant disease, leading to continued loss of life after the signing of the armistice.20African American soldiers, as with many other aspects of their military experience, received inferior medical care and were less likely to be hospitalized than their white counterparts, leading to disproportionate deaths from disease. African Americans likely faced additional risk of disease too, since they were provided inferior lodging, often camping outside even during Winter, and were often tasked with burying the dead.21 Like so many others, Will Todd died from disease after contracting meningitis. He passed away on April 8, 1919.22

Legacy

Mary Johnson, Will’s emergency contact while overseas, was likely notified by the Army of Will’s tragic passing. Mary, as well as Will’s mother and sister must have deeply felt his loss. Shortly after his death, The Fort Myers Daily Press listed Will among other Floridians that died while serving in France.23 Todd, despite the discrimination and segregation of the US, served his country honorably and with distinction. Will Todd was laid to rest and is memorialized in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, France, where he is buried in Plot B, Row 4, Grave 35.24

Endnotes

1 “World War I Service Cards,” database, Floridamemory.com (https://www.floridamemory.com : accessed June 15, 2018) entry for Will Todd.

2 Covington, W. A., History of Colquitt County. (Atlanta: Foote and Davies Company, 1937), 166.

3 “WWI Draft Registration Card, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed June 15, 2018) entry for Will Todd.

4 Many African American Floridians worked in the Turpentine industry during this period ; For more, see Bob Clarke, "Episode 23 Turpentine Industry," A History of Central Florida, podcast video, August 1, 2014, http://stars.library.ucf.edu/ahistoryofcentralfloridapodcast/22 and Jim Robison, “Museum Exhibit Review: ‘From Kin to Kant: The Culture of Turpentine’ by Robert Cassanello, Katherine Parry, Marianne McClain Popkins and Wiliam Gura”, The Florida Historical Quarterly 87, No. 3 (Winter 2009), 455-459, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20700243.

5 “WWI Draft Registration Card, 1917-1918,” Ancestry.com, Will Todd.

6 “WWI Draft Registration Card, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed June 15, 2018) entry for Walter Bascom Hobbs ; “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com https://www.ancestry.com : accessed June 15, 2018) entry for Walter Hobbs, Precinct 1, Panama City, Florida.

7 “WWI Draft Registration Card, 1917-1918,” Ancestry.com, Will Todd.

8 Jerrell H. Shofner, “Custom, Law, History: The Enduring Influence of Florida’s ‘Black Code’ ”, The Florida Historical Quarterly 55, No. 3 (Jan., 1977), 277-298, https://www.jstor.org/stable/30149151.

9 “WWI Draft Registration Card, 1917-1918,” Ancestry.com, Will Todd.

10 “U.S., Lists of Men Ordered to Report to Local Board for Military Duty, 1917-1918” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com : accessed June 15, 2018) entry for Will Todd, Army Serial Number 135.

11 “WWI Draft Registration Card, 1917-1918,” Ancestry.com, Will Todd.

12 Eric Pace, “Herbert Young, Who Fought in World War I, Dies at 112.” The New York Times, April 28, 1999, https://www.nytimes.com/1999/04/28/nyregion/herbert-young-who-fought-in-world-war-i-dies-at-112.html ; Jennifer D. Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience, (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 95.

13 Keene, World War I, 93-95.

14 “U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939.” database, Ancestry.com. (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed June 15, 2018) entry for Will Todd, Army Serial Number 4183337.

15 Pace, “Herbert Young.”

16 Keene, World War I, 103.

17 “Last Letters From Robert Lewter, Orlando Boy Who Gave Life For Country, January 22, 1919” The Orlando Sentinel, April 29, 1919, page 1, www.newspapers.com ; Pace, “Herbert Young.”

18 Pace, “Herbert Young.”

19 “Return of the 807th Pioneer Regiment, ca. 1919.” W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b219-i282.

20 Keene, World War I, 165.

21 Keene, World War I, 98-101.

22 “World War I Service Cards,” database, FloridaMemory.com, Will Todd, Army Serial Number 4183337.

23 “Casualty List: Today Had 619,” News-Press (Fort Myers, Florida), April 28, 1919, page 4, www.newspapers.com.

24 “Will Todd,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed June 15, 2018, https://www.abmc.gov/node/327693.

© 2018, University of Central Florida