Willoughby Ryan Marks (August 8, 1888–October 14, 1918)

By Glenmore Bachman and Marie Oury

Willoughby R. Marks was born on August 8, 1888, to Charles and Annie Marks, in Columbus, Georgia.1 Willoughby’s father, Charles, was a river pilot, a native of Apalachicola, Florida.2 Charles made his way to Columbus, GA using the waterway system which brought prosperity to Apalachicola in the late nineteenth century. He and Annie Ryan, also from Georgia, married on April 23, 1885, in Muscogee County, GA.3 They settled down in Columbus, Georgia4 where Willoughby (1888), Mariam (1890), Charles F. (1892), Harold (1895) and Estelle (1897) were born. Then, at some point, between 1897 and 1900, the family moved to Apalachicola to live with Mary and Mae Marks, Charles's mother and younger sister.5 In 1900, Charles Marks registered as a hotel keeper and no longer lived with the family. It is possible that he was ill and received treatment at St. Joseph’s Infirmary in Hot Springs, Arkansas.6 He passed away the same year.7 As the new breadwinner for her family, it is likely that Willoughby’s mother took over her husband’s responsibilities and became a hotel manager.8

By 1910, Willoughby was twenty one years old and worked as a bookkeeper. He had become the main provider for his family. His two younger brothers also contributed their wages in support of the family.9

Willoughby R. Marks had some military training experience when he entered the Army. Four years before the draft, he joined the Florida National Guard where he reached the rank of first sergeant.10 In 1917, when the US entered the World War I, the Army was in great need of officers and turned to the National Guard to fill some of those positions.11 Willoughby claimed his mother as a dependent to be exempt from the draft, but in light of the officer shortage, the Army rejected his request.12 Willoughby entered the Army as a first lieutenant.

Military Service

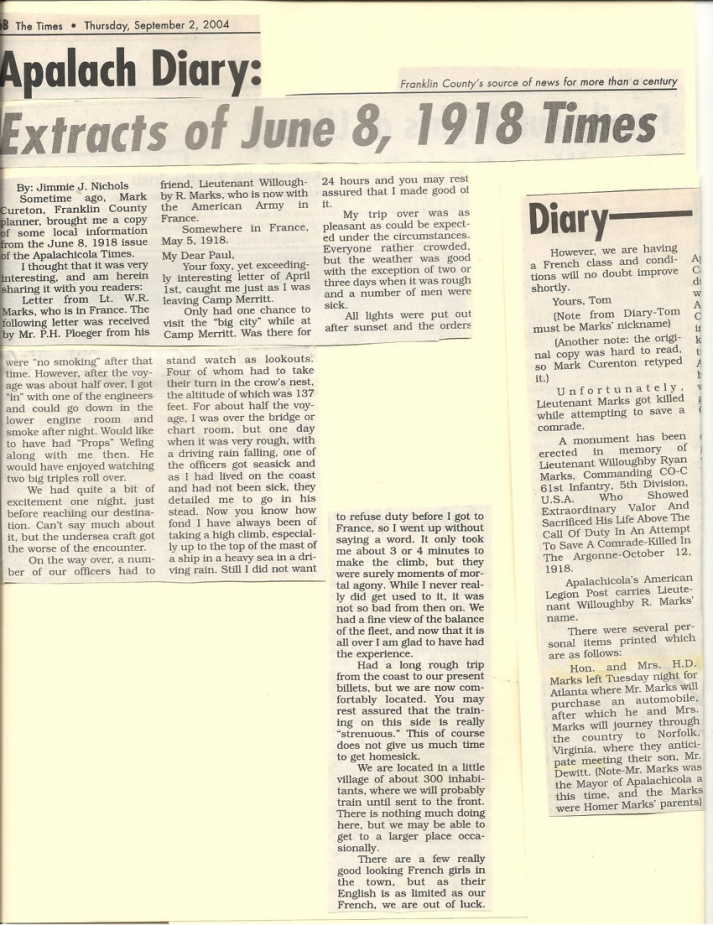

Lieutenant Marks was inducted at Camp Oglethorpe, Georgia, on November 27, 1917.13 According to Dwight D. Eisenhower, then a young officer and instructor at Camp Oglethorpe, “the training was tough and designed as much for weeding out the weak and inept as to instruct.”14 From there, Willoughby transferred to Camp Greene, North Carolina, where troops remained for thirty to ninety days while they trained in trench warfare.15 Finally, he briefly relocated to Camp Merritt, New Jersey, before shipping out at the end of April 1918 to Brest, France, on board of the SS Philadelphia.16 According to a letter Lieutenant Marks sent to a friend in Apalachicola on June 8, 1918, quoted in this news article, we know that the SS Philadelphia “had quite a bit of excitement one night… I can’t say much about it, but the undersea craft got the worse of the encounter.”17 Once in France, Lieutenant Marks described “a long rough trip from the coast to the present billet Bar-sur-Aude…a little village of about 300 inhabitants where we will probably train until sent to the front.” He also mentioned that “the training on this side is really ‘strenuous’.”18

At this point, Lieutenant Marks commanded Company C of the 61st Infantry Regiment, 5th Division.19 The 5th Division moved on June 1 to the Vosges front, in the Vosges Mountains of eastern France. First they trained with French divisions in the rear area and then from June 14 to July 16, they participated in the occupation of the Anould Sector.20 Despite the Vosges front being a quiet sector, the American troops gained valuable combat and trench warfare experience. On July 19, the 5th Division moved to the St. Die Sector of the Vosges front and led a major offensive to eradicate a salient in their line. This successful operation resulted in seizing the village of Frapelle on August 17 and in so doing consolidated a new front line.21

Then from September 12 to September 16 the 5th Division, along with the 1st, 42nd, 89th, 2nd, 90th, and 82nd, participated in the first major independent American offensive of the war at the St. Mihiel salient.22 This salient, held and fortified by the Germans for the previous four years, cut off the main supply road between the cities of Verdun and Nancy. For General Pershing, the St. Mihiel offensive was meant to create disorganization in the German lines and should have led to the Doughboys taking the Briey Bassin, where the Germans controlled iron mines and the city of Metz. Metz was a key logistic site for the Hindenburg line, a long series of German fortifications.23 The American offensive surprised the Germans. In forty-eight hours the Americans eliminated the St. Mihiel salient. They took fifteen thousand prisoners and 450 big guns.24 The 5th Division realized its objective by capturing the small town of Viéville-en-Haye, clearing the Bois Gérard right outside of Viéville-en-Haye and pushing further North-East to Souleuvre Farm.25 Due to their tenacity during the battle of St. Mihiel, the Germans supposedly nicknamed the 5th Division “Die Rote Teufel” or “Red Devils,” a nickname still used today for the 5th Division.26 But the price for the St. Mihiel offensive was high, with 7,000 American casualties. Moreover, General Pershing had to withdraw his main objective of Metz, following the orders of Marechal Ferdinand Foch, the French General and Supreme Allied Commander, who was preparing for a bigger strategic offensive in Meuse-Argonne.27

The Meuse-Argonne offensive started on September 26, 1918. It was part of a large synchronized attack organized by the Allied forces which ran from the North Sea to the Meuse River. The objective for the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was to gain control of the German railroad system which ran along the front northwest of Reims and to cut off the supply road on the Hindenburg line.28 With 1.2 million American soldiers fighting for forty-seven days, the Meuse-Argonne offensive remains today the bloodiest American battle of all time with 26,677 dead and 95,786 wounded.29 The 5th Division deployed on October 5 as part of III Corps. On the first days of the offensive, III Corps was in charge of the area between Montfaucon and the Meuse River; its main objective was to protect V Corps’ right flank. V Corps had the difficult task of attacking the German fortified observatory on the heights of Montfaucon.30 By October 3, III and V Corps had secured the area and advanced toward the outpost defenses of the Hindenburg line. Between October 12 and October 14 the 5th Division captured Cunel and started clearing the Bois de Pultière and the Bois de Forêt.31 During this action, Lieutenant Marks was severely wounded but refused to leave his company before achieving its objective. He then heard that his best friend, Second Lieutenant George Hollister, was lying wounded outside the trench. Under intense enemy fire, Marks rushed to save his friend when high-explosive shellfire struck and killed both of them.32

Legacy

First Lieutenant Willoughby Ryan Marks rests in the Meuse Argonne Cemetery along with 14,246 other American soldiers.33 The Army informed his mother of his death and she received, on her son’s behalf, a Distinguished Service Cross medal.34 Later, in the 1930s, while we are not sure if Mrs. Marks participated in a Gold Star family visit to the cemetery, she certainly showed interest in participating in this mothers’ pilgrimage to visit her son’s grave in France.35

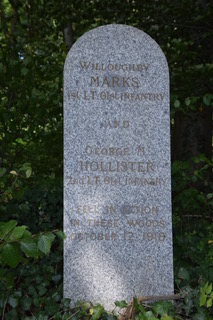

To honor a fallen son of the city, Apalachicola erected a small granite monument which reads: “In Memory of Lieutenant Willoughby Ryan Marks Commanding Co C, 61st Inf., 5th Division U.S.A. who showed extraordinary valor and sacrificed his life above the call of duty in an attempt to save a comrade. Killed in the Argonne, October 12, 1918.”36 The Apalachicola Legion Post 106 in Florida, established after World War I, carries Willoughby R. Marks’ name in memory of his sacrifice.37 Furthermore, in the past hundred years, on different occasions, local newspapers have celebrated Lieutenant Marks to remind readers of the valor and courage of this young man.38

In France, the 5th Division’s men built twenty eight markers to locate the sites where they encountered heavy combat, twenty four of those are in the Meuse-Argonne battlefield.39 In addition to those markers, there is the stele, pictured here, to remember where 1st Lieutenant Willoughby Marks died, trying to save his best friend, George Hollister.

Endnotes

1 “United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed May 31, 2018) entry for Willoughby Marks; “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed May 31, 2018) entry for Willoughby Marks.

2 “1870 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed June 3, 2018) entry for Charles Marks.

3 “County Marriage Records, 1828–1978. The Georgia Archives, Morrow, Georgia,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed May 31, 2018) entry for Charles Marks and Annie Ryan.

4 “ U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995: Columbus, Georgia, City Directory, 1894,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed May 31, 2018) entry for Charles Willoughby Marks.

5 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com, Willoughby Marks.

6 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed June 3, 2018) entry for Charles Marks.

7 Database, FindaGrave.com (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/26477034/charles-willoughby-marks: accessed June 3, 2018) entry for Charles Willoughby Marks.

8 “1900 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, Willoughby Marks.

9 “1910 United States Federal Census”, database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed June 3, 2018) entry for Willoughby Marks.

10 “United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” Ancestry.com, Willoughby Marks

11 Richard Shawn Faulkner, The School of Hard Knocks: Combat Leadership in the American Expeditionary Forces (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2012), 26-68.

12 “United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” Ancestry.com, Willoughby Marks

13 “WWI Service cards”, database, Floridamemory.com (https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/205438: accessed June 20, 2018), entry for Willoughby Marks.

14 Shawn Faulkner, The School of Hard Knocks, 42.

15 Edward S. Perzel “WWI Boot camp in Charlotte,” article from Tar Heel Junior Historian, published for the Tar Heel Junior Historian Association by the North Carolina Museum of History. (Accessed June 3, 2018.) https://www.ncpedia.org/wwi-boot-camp-charlotte.

16 Army War College's Historical Section, Special Staff's Historical Division, Order of the Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War, vol 2 (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History United States Army, 1931), 78; Jimmie J. Nichols, "Apalach Diary," Apalachicola Times, September 2, 2004, (Accessed May 31, 2018). https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/collection/1030/tree/119545525/person/390182917689/media/39b1a21d-35d9-485c-a24a-8b5ba44d6f27?_phsrc=JmQ56&usePUBJs=true. In May of 1918, a month after Marks went oversees, the Navy took control of the SS Philadelphia and renamed it the USS Harrisburg. After the war, it reverted back to private hands, becoming the SS Philadelphia again. United States Navy Temporaty Auxillary Ships, World War I, Index, (accessed August 28, 2018), http://www.shipscribe.com/usnaux/ww1/ships/yale.htm.

17 Jimmie J. Nichols, "Apalach Diary," Apalachicola Times.

18 Army War College's Historical Section, Special Staff's Historical Division, Order of the Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War, vol 2, 81; Jimmie J. Nichols, "Apalach Diary," Apalachicola Times.

19 Jimmie J. Nichols, "Apalach Diary," Apalachicola Times.

20Army War College's Historical Section, Special Staff's Historical Division, Order of the Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War, vol 2, 81.

21 American Battle Monument Commission, American Armies and Battlefields in Europe: A History, Guide, and Reference Book, (Washington, D.C., 1938), 423.

22Army War College's Historical Section, Special Staff's Historical Division, Order of the Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War, vol 2, 83; American Battle Monument Commission, American Armies and Battlefields in Europe, 109.

23 Robert H Zieger, America’s Great War: World War I and the American Experience, (Oxford, England: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2000), 96.

24 Edward G. Lengel, To conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918. The Epic Battle That Ended the First World War, (New York, New York: A Holt paperback, 2008), 324.

25 Army War College's Historical Section, Special Staff's Historical Division, Order of the Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War, vol 2, 83; American Battle Monument Commission, American Armies and Battlefields in Europe, 142.

26 Edward J. Barta, The Fifth Infantry Division: World War I, (accessed June 21, 2018), http://www.societyofthefifthdivision.com/WWI/WW-I.html.

27 Richard Rubin, The Last of the Doughboys: the Forgotten Generation and their Forgotten World War, (New York, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2013), 324.

28 American Battle Monument Commission, American Armies and Battlefields in Europe, 167.

29 Lengel, To conquer Hell, 4.

30 American Battle Monument Commission, American Armies and Battlefields in Europe, 173.

31 American Battle Monument Commission, American Armies and Battlefields in Europe, 181; Army War College's Historical Section, Special Staff's Historical Division, Order of the Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War, vol 2, 85.

32 The Office of the Adjutant General of the Army, American Decorations 1862-1926 : Published by the order of the Secretary of War , vol.1, (Washington D.C: United States Government Printing Office, 1927) 438; “Marks Memorial to be erected: Citizens will honor hero who was killed in France” Pensacola Journal (August 15, 1920): second section, page 12, Chronicling America, accessed June 21, 2018. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/Depending to the sources, there are two different dates for when 1st Lieutenant Willoughby Ryan Marks died. His service card and the American Battle Monument Commission mention October 14, 1918. The monument in Apalachicola, the stele in France and the citation for the award of the Distinguished Service Cross mention October 12, 1918.

33 “American Battle Monuments Commission: Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery”, (accessed June 19, 2018) https://www.abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials/europe/meuse-argonne-american-cemetery#.WymdWqczbZY.

34 “WWI Service cards”, Floridamemory.com, Willoughby Marks; American Battle Monument Commission, Burial and Memorial Search, https://www.abmc.gov/database-search (accessed June 19, 2018) entry for Willoughby Marks.

35 “U.S. World War I Mothers' Pilgrimage, 1929”, database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed May 31, 2018) entry for Willoughby Marks.

36Gaines, James L. Gibson Inn located at 51 Ave. C in Apalachicola, Florida. 1993. Black & white photonegative, 60 mm. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, accessed september 13, 2018, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/131631; “Lt. Willoughby Ryan Marks - Apalachicola, Florida, USA. - Specific Veteran Memorials on Waymarking.com,” last modified December 31, 2017, accessed September 13, 2018, http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WMXDNP_Lt_Willoughby_Ryan_Marks_Apalachicola_Florida_USA.

37 “AVSOPS, Directory, World War I, The American Legion,” American Veterans Service Organizations and Patriotic Societies, (accessed June 27), 2018, http://www.avsops.com/american-legion/legion-32329-post.

38 “Marks Memorial to be erected: Citizens will honor hero who was killed in France” Pensacola Journal (Pensacola, FL) August 15, 1920; Michael Browning, “The War to End all Wars!”, The Palm Beach Post (West Palm Beach, FL), November, 11, 2002; Jimmie J. Nichols, "Apalach Diary," Apalachicola Times, September 2, 2004, Alec Hargreaves “Marking an American hero’s centenary,” Apalachicola and Garrabelle Times (Apalachicola, FL) June 15, 2018.

39 For an example of, and information about the 5th Division markers see: American War Memorials Overseas, “5th Division Stele of Doulcon,” (accessed June 27, 2018), http://www.uswarmemorials.org/html/monument_details.php?SiteID=536&MemID=806.

© 2018, University of Central Florida