William Snow Taylor, Jr. (June 28, 1888–September 25, 1918)

By Mackenzie Knapp and Brandon Nightingale

Early Life

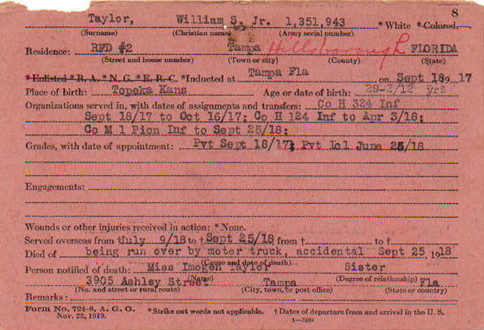

William Snow Taylor Jr. was born to Celestia Taylor and William S. Taylor Sr. in Topeka, Kansas on June 29, 1888.1 Taylor Sr., born to a German father, served in the US Military Telegraph Corps during the Civil War.2 In his later years, Taylor Sr. worked as a fruit grocer, while his wife Celestia raised their three children. Taylor Jr. had two older sisters, Imogene (1979) and Eugenia (1985); all of them received an education at an early age. Although Taylor Jr. was born in Topeka Kansas, by the time he was twelve years old the family had moved to Hillsborough County, FL, where they owned property. The move was likely due to William Taylor Sr.’s employment.3 Like his father, William S. Taylor Jr., served in the US Army, drafted in 1917, in Tampa, FL. According to his service card, at the time of his enlistment, Taylor was twenty-nine years old.4

Military Service

On September 18, 1917 William S. Taylor Jr. was assigned to Company H of the 324th Infantry Regiment of the 81st “Stonewall” Division of the US Army.5 The 81st Division became known as the “Wildcat” Division in World War I. The name originated at Camp Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina, where feral cats thrived near “Wildcat Creek.” Colonel Halstead and the division staff adopted the shoulder insignia based on the drawings of Sgt. Dan Silverman, Headquarters Company, 321st Infantry. Legend has it that they earned the nickname in the Vosges Mountains and in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, when they fought the Germans like “wild cats.”6

Taylor joined Company H of the 124th Infantry on October 16, 1917 while training in South Carolina, just one month after being drafted.7 When the 1st and 2nd Regiments consolidated and reorganized on October 1, 1917, as part of the mobilization for World War I, it became the 124th Infantry assigned to the 31st Division.8 During October, the division was reinforced with 10,000 men from Alabama, Florida, and Georgia, transferred from Camps Gordon, Jackson, and Pike, as it began systematic training on October 22nd.9 Taylor served in the 124th until April 3, 1918, at which time he was reassigned to Company M of the 1st Pioneer Infantry Division.10

On June 25, 1918 Taylor Jr. was promoted to Private First Class while serving with Company M of the 1st Pioneer Infantry Regiment.11 Prior to and during the First World War, Pioneers, which included significant numbers of African-American soldiers who did much of the difficult manual labor, engaged in the construction and repair of military railways.12 Taylor likely joined the Pioneers to train at Camp Wadsworth, South Carolina, before heading to Camp Mills, New York, on July 3. After training, the 1st Pioneers headed to their port of embarkation at Hoboken, New Jersey, where they boarded the USS Orizaba and sailed on July 9, arriving in Brest, France, on July 18. By July 24 they were already on the Marne River east of Paris.13 Arriving in the town of Chateau-Thierry right after the Allied capture of the city on July 21, the 1st Pioneers witnessed the devastation of modern artillery and encountered French villagers who had survived the German occupation and shouted “Vive L’Amerique.”14

Company M then joined the 308th Engineers continuing their work right behind the front lines. By September 6, the 1st Pioneers arrived near Fismes, part of the Aisne-Marne Offensive, on foot. From there, Company M was sent to Courmont where, along with the 77th Division, they did salvage work in the area until September 17.15

Then, in the lead up to the massive Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the 1st Pioneers camped in the woods of Osches, where they remained for several days. To ensure that the Germans did not know the Americans were amassing troops in the area, the regiment only moved at night. After a few days in these rough conditions, they marched forward again toward Fromereville. As the men passed through the town and headed for a nearby wooded area, they came came under enemy fire. Troops, guns, and wagons, crowded on the roads, sought cover as “shell after shell” landed and shouts echoed throughout the town. The regiment eventually made it to the woods, where it waited for orders to help prepare for the massive offensive.16 The 1st Pioneers work was a vital to the final Allied offensive the war. The Meuse Argonne occurred over forty-seven days from September 26, 1918, until the Armistice of November 11, 1918; it was the largest and bloodiest operation of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), commanded by General John J. Pershing. About 1.2 million American soldiers fought, of which 95,786 men were wounded and 26,277 Americans lives were lost.17

On the day leading up to the battle, ten American divisions of 26,000 men were poised to attack. They were organized in three corps, arrayed facing north from the edge of the Champagne region in the west to the Meuse River in the East.18 Company M arrived the night before in trucks from the Vesle front and was split up into three platoons and attached to the 80th, 33rd , and 4th divisions.19 William S. Taylor Jr. was likely part of the massive movement of men and material taking place in the middle of the night to avoid alerting the Germans of the impending attack. Men marched in the dark on either side of a massive convoy of trucks, tanks, and horse drawn carts—everything the US Army needed to launch a massive offensive. Nothing could stop the convoy and Taylor was accidentally run over by a motor truck and died on September 25, 1918.20

Legacy

Although he died tragically in the preparations for the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, William Taylor Jr.’s legacy remains one hundred years after his death. He rests with over 14,000 other Americans in the Meuse Argonne American Cemetery, which sits on part of the battlefield. It is the largest American cemetery in Europe, covering over 130 acres.21 He is buried in Plot G, Row 22, Grave 40.22

Endnotes

1 “Taylor S. William Jr.” American Battle Monuments Commission (accessed June 28, 2018, https://www.abmc.gov/node/338464#.WztqXdJKjD5). See also: “PFC William Snow Taylor, Jr,” Find A Grave (accessed June 17, 2018: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/115368596/william-snow-taylor).

2 “William Snow Taylor, Sr. (October 9, 1845–February 21, 1925),” Myrtle Hill Memorial Park, Tampa, Hillsborough County, FL, Find A Grave, (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/51824165/william-snow-taylor: accessed June, 27, 2018).

3 "United States Census, 1900,", FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M369-ZJK, accessed June 18, 2018), William S. Taylor in household of William S. Taylor Sr.

4 “World War I Service Cards, William S. Taylor,” Florida Memory, (https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/228556, accessed June 18, 2018).

5 World War I Service Cards, William S. Taylor,” Florida Memory. (https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/228556: Accessed June 18, 2018).

6 Clarence Walton Johnston, The History of the 321st Infantry, With a Brief Historical Sketch of the 81st Division, (Columbia, S. C.: The R. L. Bryan Company, 1919), 133; “Insignia 81st (Stonewall) Division,” Base Printing Plant, 29th Engrs., U.S. Army 1919, (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AInsignia_81st_(Stonewall)_Division%2C_American_Expeditionary_Forces%2C_France_1918-19.tif); United States, Army 324th Infantry, Combat History Of The 324th Infantry Regiment, 44th Infantry Division (Baton Rouge: Army & Navy Pub. Company, 1946), 12.

7 “William S Taylor,” Florida Memory.

8 “124th Infantry Regiment (First Florida),” Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, last modified as of October 21, 2010. (https://history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/lineages/branches/inf/0124in.htm: accessed October 1, 2018).

9 United States Army, Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War American Expeditionary Forces: Divisions. Vol 2 (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 1988), 173.

10 World War I Service Cards, William S. Taylor,” Florida Memory.

11 World War I Service Cards, William S. Taylor,” Florida Memoryp>

12 Thomas P. Dooley, Irishmen Or English Soldiers? The Times and World of a Southern Catholic Irish Man (1876–1916) Enlisting in the British Army During the First World War (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1995), 170.

13 “United States Army Transport Service –Passenger List of Organizations and Casuals,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 7, 2018) Entry for overseas visitors including William S. Taylor. Chester W. Davis, The Story of the First Pioneer Infantry (Utica, NY: Kirkland Press), 11-13.

14 Davis,The Story of the First Pioneer Infantry, 11, 14-15.

15 Davis, ,The Story of the First Pioneer Infantry, 21-22.

16 Davis, ,The Story of the First Pioneer Infantry, 24.

17 Edward G. Lengel, To Conquer Hell (New York: Henry Holt, 2008), 4.

18 Edward G. Lengel, To Conquer Hell, 2, 186-193.

19 Davis, The Story of the First Pioneer Infantry, 24.

20 “World War I Service Cards, William S Taylor,” Florida Memory (https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/228556) (Accessed June 18, 2018).

21 “Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery”Overview, accessed June 29, 2018, https://www.abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials/europe/meuse-argonne-american-cemetery#.W6vIhXtKiHt.

22“Taylor S. William Jr.” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed June 28, 2018, https://www.abmc.gov/node/338464#.WztqXdJKjD5.

© 2018, University of Central Florida