Private Riley Wright (September 4, 1893–January 7, 1919)

By Abigail Robinson

Early Life

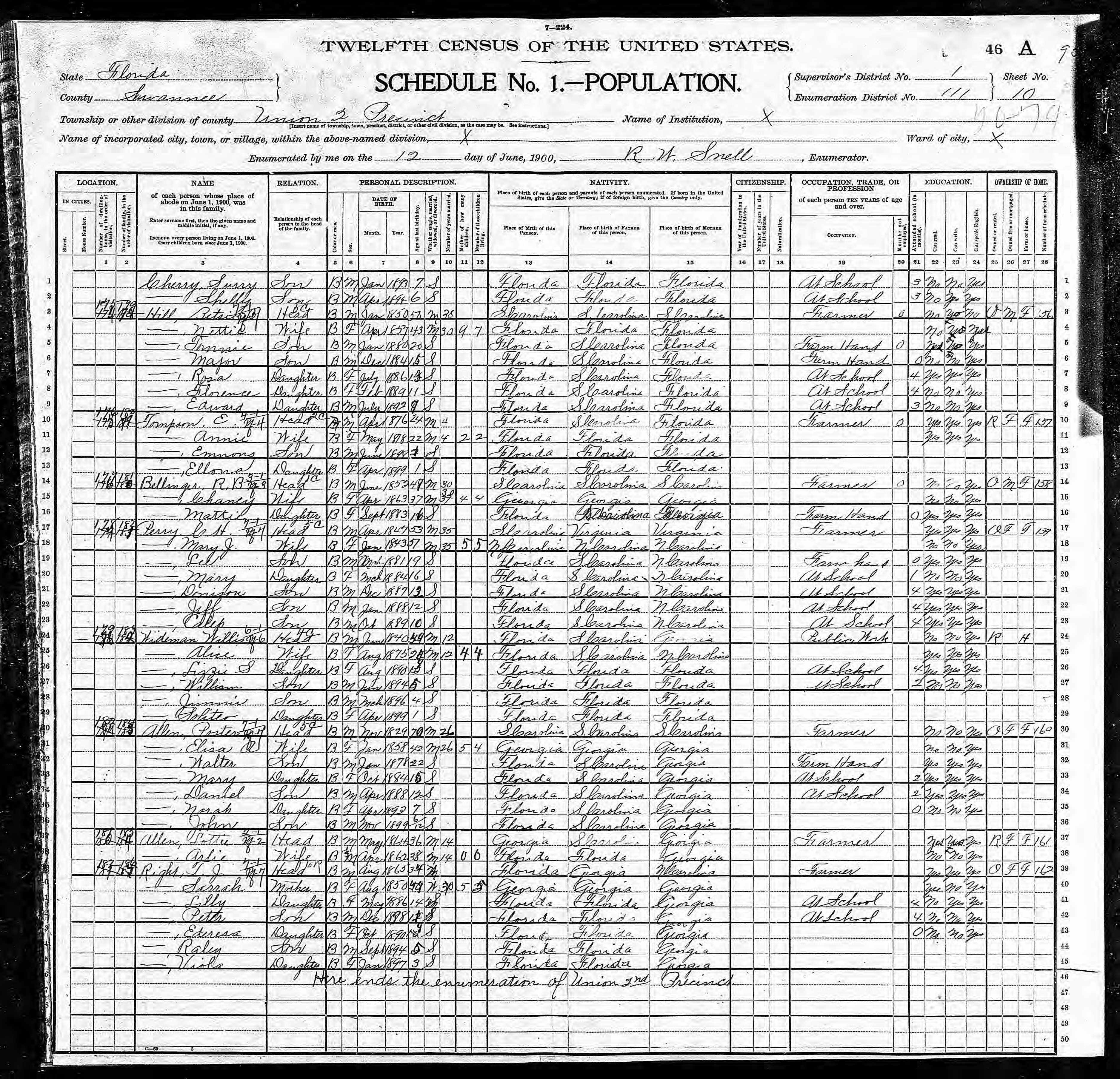

On September 4, 1893, Riley Wright was born in Falmouth, an unincorporated community in Suwannee County, Florida. According to the 1900 Census, Riley lived in Suwannee County with his father, Turner J. Wright, and paternal grandmother, Sarah, who filled the void left by Riley’s absent or deceased mother. The Wright family also included Riley’s older siblings Lilly, Peter, and Ederesa, and a younger sister Viola.1 Like many African American men in the rural South after the Civil War, Riley’s grandfather Robert and his father Turner worked as farmers in Suwannee County. The vast majority of black Southerners worked as tenants, sharecroppers or wage hands, and while many blacks dreamed of owning their own land, cycles of debt to landlords and store creditors saw increased indebtedness to whites with few achieving land ownership. Yet by the 1900 Census, Riley’s father Turner, as seen here in census, line 39, listed as TJ Right, owned their family home free of mortgage and likely farmed on his own land.2 Riley likely attended primary school, though he eventually followed his father into farming. By 1917, Wright worked for a white employer, William McGregor, on McGregor's farm near Live Oak, FL. On April 15, 1917, Wright married Eva Coleman, also a native of Suwannee County.3

Military Service

After the US entry into World War I, Congress, on May 18, 1917, passed the Selective Service Act to increase the manpower of the US military through conscription. The first registration act on June 5, 1917 required all men in the US between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-one to register. Over ten million men registered, including Wright at age of twenty-four.4 At the risk of losing their workforce, many powerful white landowners in the South used their influence to gain exemptions for their black tenants from local draft boards. Other blacks, however, without powerful white patrons, saw their claims of exemption because of family dependents denied. White-controlled draft boards argued that sending impoverished blacks into the military improved their financial standing as soldiers’ thirty-dollar monthly allowance provided more income to a black family than sharecropping. Thus nationwide, the military drafted one-third of black registrants, compared to one-fourth of all white registrants.5 On August 3, 1918, the Army formally inducted Wright into military service where he trained at Camp Devens in Ayer, Massachusetts.6

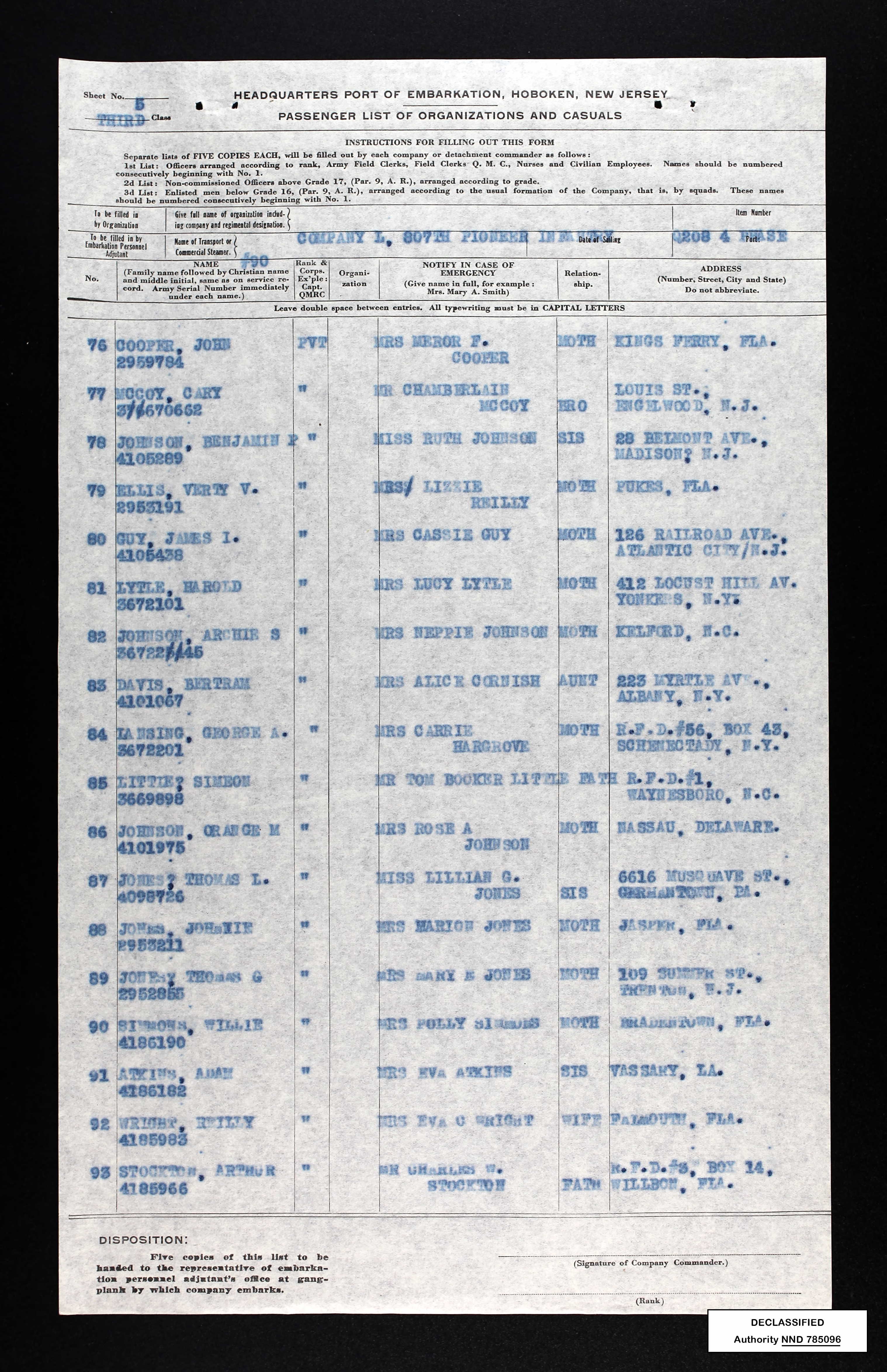

Despite black soldiers’ willingness to serve on the front lines, most served in noncombatant units amid the Jim Crow era of enforced racial segregation. Whites, particularly Southerners, feared the consequences of blacks using their military experiences, such as firearm training, to initiate a racial war. Thus, the War Department sought to utilize blacks in non-threatening roles within special stevedore and labor battalions along with the pioneer infantry, working to dig ditches, build roads, and serve as drivers and cooks.7 As such, after training at Camp Devens, on August 26, 1918, Wright joined Company L of the 807th Pioneer Infantry. The regiment organized at Camp Dix, New Jersey in July of 1918, serving as one of sixteen black pioneer regiments formed to replace white units slated for conversion into infantry regiments. On September 15, the regiment, as seen here on the passenger list, no. 92, embarked from Hoboken, New Jersey to join the war effort in France.8

Considered among the elite regiments for black troops, pioneer infantries consisted of white officers and black troops along with specialists such as mechanics and carpenters. Serving in a technical capacity, these regiments constructed and repaired roads, bridges, and railroads. While the Army did not consider pioneer infantry as combat units, their work on the front lines along with shifts in the lines of combat meant these units experienced direct action with the enemy. While many black soldiers felt slighted by having to perform these duties and face humiliation, mistreatment, and outright brutality, Wright and other black soldiers contributed greatly to the overall war effort. Wright and the 807th took part in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the last major engagement of the war beginning on October 26, 1918. While serving as a non-combat unit during the offensive against the Germans, the regiment shared in the hardship on the front lines. A contemporary of Wright, who served in the 807th, reflected on wielding bayonets against the Germans and becoming sick from poison gas, showing the intensity of battle. The war ended on November 11, 1918 with an armistice and German defeat.9

Although Wright survived the war, he succumbed to the pervasive influenza and pneumonia epidemic which killed more US soldiers and individuals across the world than enemy weapons. While segregation ironically shielded some black regiments from the influenza infection, overall black regiments experienced higher mortality rates than whites regiments. White medical officers claimed that African Americans’ inferiority made them more susceptible to pneumonia. Black soldiers’ reluctance to seek the medical care of discriminatory white doctors or these doctors dismissive attitudes about black soldiers’ complaints of sickness meant that many entered the hospital sicker than white soldiers. The factors of inferior living conditions, insufficient clothing and food, and hard outdoor, manual labor, including burial duty, often in inclement winter weather, further intensified the spread of the disease among black troops.10 On January 7, 1919, Wright, only twenty-four years old, died as a result of lobar pneumonia with his wife Eva back in Falmouth notified of his passing.11

Legacy

As many black women needed to work in farming or domestic labor to supplement their family’s livelihood, the loss of Riley certainly impacted his wife Eva emotionally and financially. Widows often faced greater vulnerabilities to poverty and many quickly remarried for economic security. Thus, on November 15, 1919, Eva married Cleveland Hutchinson, another black man from Falmouth.12

Despite facing pervasive discrimination, the families and neighbors of black soldiers celebrated and expressed pride for African Americans’ service and sacrifice. As the remnant of Wright’s 807th Pioneer Infantry returned to the US, W.E.B. DuBois, among the most prominent black leaders in the country, celebrated the regiment as a “compliment to our race.” DuBois detailed the pride of the black community towards some in the unit earning the French Croix de Guerre and the 807th being described for their “bravery and cheerfulness in the performance of duty.”13 Additionally, on April 19, 1919, General Pershing issued an order awarding the 807th regiment the Silver Band to be engraved and placed upon the Pike of Colors of Lance of the Standard for their participation in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Wright’s legacy reflects fighting for freedoms denied to him in his own country because of his race. Yet in spite of the challenges of racism, Wright’s service and sacrifice show his distinctive contributions to America. Riley Wright is interred in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, Plot H Row 10 Grave 28 in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, France.14

Endnotes

1 “WWI Service Cards,” database, FloridaMemory.com, (https://www.floridamemory.com : accessed March 26, 2018), entry for Riley Wright; “1870 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed June 10, 2018), entry for Turner Wright, Subdivision 9, Suwannee, Florida; “1900 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed March 26, 2018), entry for Raley Right, ED-0111, Union, Suwannee, Florida.

2 Leon F. Litwack, Trouble In Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1998) 128-130.

3 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed April 26, 2018), entry for Ralie Wright, “1920 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed June 12, 2018), entry for William R McGregor, ED-152, Falmouth, Suwannee, Florida; “Florida County Marriage Records, 1823-1982.” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed: April 26, 2018), entry for Eva Coleman and Waralley Wright, Suwannee County, Florida.

4 “World War I Draft Registration Cards,” National Archives, accessed June 15, 2018, https://www.archives.gov/research/military/ww1/draft-registration; “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” Ancestry.com, Ralie Wright.

5 Jennifer D. Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 33-37.

6 “U.S., Lists of Men Ordered to Report to Local Board for Military Duty, 1917–1918,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed June 10, 2018), entry for Riley Wright.

7 Keene, World War I, 95; Derrel B. Depasse, Traveling the Rainbow: The Life and Art of Joseph E. Yoakum (New York/Jackson, MS: Museum of American Folk Art/University Press of Mississippi: 2001), 11.

8 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” Ancestry.com, Ralie Wright; “U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed April 26, 2018), entry for Reilly Wright; Richard A. Rinaldi, The United States Army in World War I: Orders of Battle, Ground Units, 1917-1919 (n.p.: Tiger Lily Publications, LLC, 2005), 101, 104.

9 Derrel B. Depasse, Traveling the Rainbow, 11; Eric Pace, “Herbert Young, Who Fought In World War I, Dies at 112,” New York Times, April 28, 1999; Addie W. Hunton and Kathryn M. Johnson, Two Colored Women With the American Expeditionary Forces (Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Eagle Press, 1920), 121; Tammy M. Proctor, Civilians in a World at War: 1914-1918 (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 56.

10 Keene, World War I, 167-168; Carol R. Byerly, "The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919." Public Health Reports 125, no. Suppl. 3 (2010), 82, 88, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2862337/; Pace, “Herbert Young, Who Fought in World War I, Dies at 112.”

11 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Riley Wright.

12 Harry T. Reis and Susand Sprecher (eds.), “Remarriage,” Encyclopedia of Human Relationships, Vol. 1 (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2009), 339; Anne Valk and Leslie Brown, Living with Jim Crow: African American Women and Memories of the Segregated South (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2010), 81; “Florida County Marriage Records, 1823-1982.” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed: June 15, 1919), entry for Eva Wright and Cleveland Hutchinson, Suwannee County, Florida.

13 Return of the 807th Pioneer Regiment, ca. 1919, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, MS 312, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, Amherst, MA. http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b219-i282.

14 Hunton and Johnson, Two Colored Women With the American Expeditionary Forces, 120; "Riley Wright." American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed April 26, 2018, https://www.abmc.gov/node/338847#.WuIBo-jwY2w.

15 "Riley Wright." American Battle Monuments Commission. Accessed April 26, 2018. https://www.abmc.gov/node/338847#.WuIBo-jwY2w.

© 2018, University of Central Florida