Sampson Dolliver Dodrill (August 8, 1888–September 28, 1918)

By Jonathan Foster and Marie Oury

Early Life

Sampson Dolliver Dodrill was born August 8, 1888 in Webster Springs, West Virginia, the first of John L. and Rebecca Dodrill’s five children. Sampson grew up as one of five boys, with brothers Addison Rucker (1892), Walker (1896), Horbart (1899), and Forest (1902). The Dodrills lived in a multi-generational home, as the children’s paternal grandfather, Addison Dodrill, also lived with them.1 According to current residents of Webster Springs, it is likely that Sampson and his family farmed corn and potatoes.2

Sampson Dodrill migrated to Central Florida between 1910 and 1917. On his draft registration card, dated June 5, 1917, Sampson indicated that he worked for the Winter Park Fruit Company, but did not provide an exact address in Winter Park on the military registration form. Back in Wester County, West Virginia, Sampson’s two brothers Rucker and Walker also registered for the draft, on June 5, 1918.3

Military Service

Sampson Dolliver Dodrill was officially inducted into the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) on April 26, 1918 in Webster Springs, West Virginia. He began his training the next day at Camp Meade, Maryland, as a Private in the 10th Training Battalion of the 154th Depot Brigade. On June 14, 1918 he was assigned to Company G of the 314th Infantry which was part of the 79th Division.4 Camp Meade had around 2,000 buildings, costing roughly eighteen million dollars to construct and training up to 54,000 soldiers at a time.5 A total of 95,000 soldiers trained at Camp Meade but only 27,000 served in the 79th Division. Out of the 27,000 soldiers forming the 79th Division, 15,000 arrived to train with Dodrill in June 1918.6

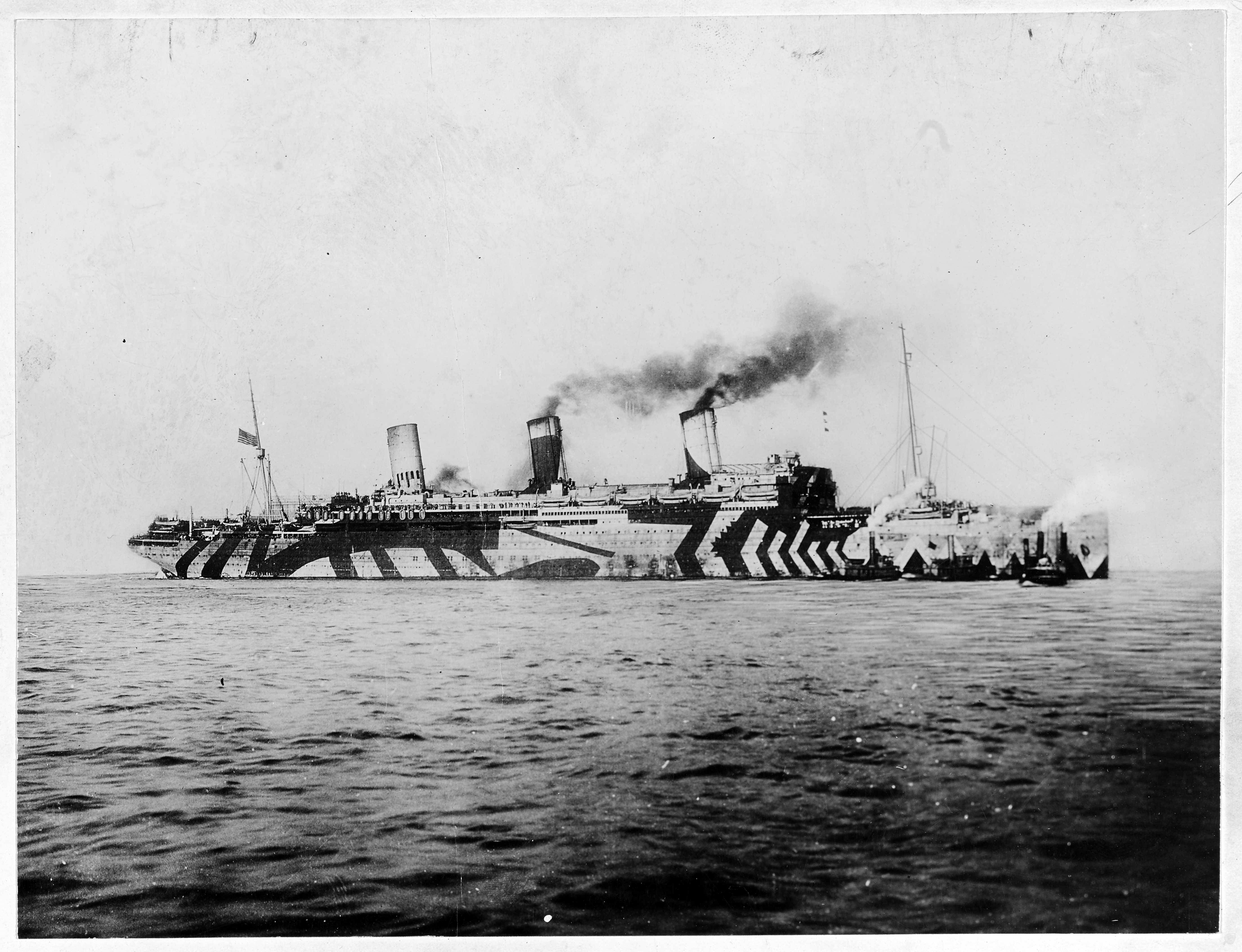

On July 6, 1918, the 314th Infantry took a train heading toward Hoboken, New Jersey, to embark aboard of the massive USS Leviathan, one of the largest ships in the world at the time.7 Captain H.F. Bryant and the crew of the USS Leviathan carried over 10,000 military personnel to France. On the journey over the Atlantic Ocean, soldiers’ practiced abandon-ship drills because of the danger of German submarine attacks. The ship was apparently so hot and stuffy that soldiers sought to escape by bunking outside on the ship’s deck to get a good night’s rest. After ten days at sea, on July 16, the USS Leviathan safely docked in the port city of Brest, on the northwestern coast of France.8

In France, the 79th Division traveled by train, in French box cars, to its training area at Prauthoy, Haute-Marne, about two hundred miles southeast of Paris. By the beginning of August, the men trained up to eight hours per day, under French officers and American specialists who wanted to ready them for what lay ahead. Influenza also began to spread and by late August the Division had 600 cases of the flu with a four percent mortality rate.9

On September 9, the 79th Division transferred to the Meuse front, in the quiet Blécourt sector, southwest of Verdun. The Division relieved part of the French 157th Division, which had been holding about two and a half miles in the vicinity of Avocourt. Relatively quiet in the summer of 1918, this area included the battlefields of Verdun, where major combat had taken place in 1916 between the French and the Germans on Hill 304 and a place that came to be known as le Mort Homme (the dead man). While in this sector, Private Dodrill did not experience front line combat; the 314th Infantry stayed in reserve in Camp Deffroy, North of the village of Dombasle-en-Argonne. The 79th Division was relieved on September 23 in order to begin preparations for the final, major battle of World War I.10

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive, which began September 26, 1918, was part of a coordinated Allied plan, with four synchronized assaults along much of the Western Front from the Flanders region in the north to the Meuse River further south, in order to push back the German line. To supply the front and move their troops, the Germans used a railroad line running along the front, from Lille to Thionville. The Americans’ main objective was to cut this line in the area of Sedan and Mézière in order to disorganize and prevent German supplies from getting to the battlefields and hasten the end of the war.11 The first movement of this assault pushed towards the Hindenburg Line, which many officers believed impossible to breech. Starting from the outpost of the Avocourt-Malancourt line, the 79th Division had the objective, on the first day, to seize successively the villages of Malancourt, Montfaucon and Nantillois. Representing a total five and a half miles, it was the deepest first day objective of the entire Meuse-Argonne front.12 The movement started at 5:30 a.m. and both the 313th and 314th Infantry worked together as the head of the 79th Division. The 313th advanced on the left side of the line, while the 314th struck from the right. While the soldiers moved towards Malancourt it was difficult maneuvering through the fog and barbed wire. The fog was so thick that the 314th Infantry passed by enemy machine gun nests undetected. By 7:30 a.m., the 314th Infantry successfully bypassed Malancourt and was ready to proceed to Montfaucon, a ruined village on top of a 1,122-foot-high hill which dominated the Meuse Argonne region.13 Through the fours years of war, the Germans had turned it into an observation post and kept reinforcing it, constructing trenches, gun positions, entanglements and pill boxes. Around 9:00 a.m., the fog cleared and both the 313th and the 314th infantry took heavy machine gun fire from multiple directions, suffering many casualties. Fierce German opposition assaulted the 79th Division at the bottom of the Montfaucon heights and blocked the advance for the rest of the day.14On September 27, the 314th Infantry continued to fight uphill on the east side of the Montfaucon heights crossing fields leading upward to the woods, Bois de la Tuilerie. In the woods, the 314th Infantry encountered ferocious resistance, worsened by a pouring rain. By noon, with reinforcements from the 315th Infantry, Private Dodrill and the rest of 314th Infantry finally reached the ruins of the Montfaucon village. The men were exhausted, fighting with little sleep, no water, and only the rations they carried with them for two days.15 Concealed in the ruins, the Americans discovered seventeen reinforced observation posts, including a reinforced concrete tower with a telescopic periscope, which had allowed the Germans to visualize everything from the heights of Verdun to the edge of the Argonne Forest.16 Once the 79th Division seized the hill and its strategic views, the 314th Infantry continued pushing forward, stopping roughly one-half mile from Nantillois. Unable to reach the German controlled village, the men held a defensive line, about one mile long, just south of the objective that the Allied high command had set for them on the first day. In planning the objectives, the AEF high command had high expectations which most of the American divisions did not achieve, stalled on strong German defenses. Only the extreme right side of the Meuse-Argonne battle front, with the III and V Army Corps, had reached the objectives on the first day.17 Moreover, in a war characterized by stalemate for nearly four years, these men moved the front line nine miles in just three days. Private Dodrill died on September 28, a day the 314th Infantry suffered from heavy German shelling. Although in reserve after two days of front line fighting, the men of the 314th advanced to ensure the Allies did not lose ground. As the Germans were so well-entrenched in the area, the First Army continued to encounter machine gun nests that survived the first rush. Dodrill’s unit suffered significant losses and was officially relieved on September 29, 1918.18

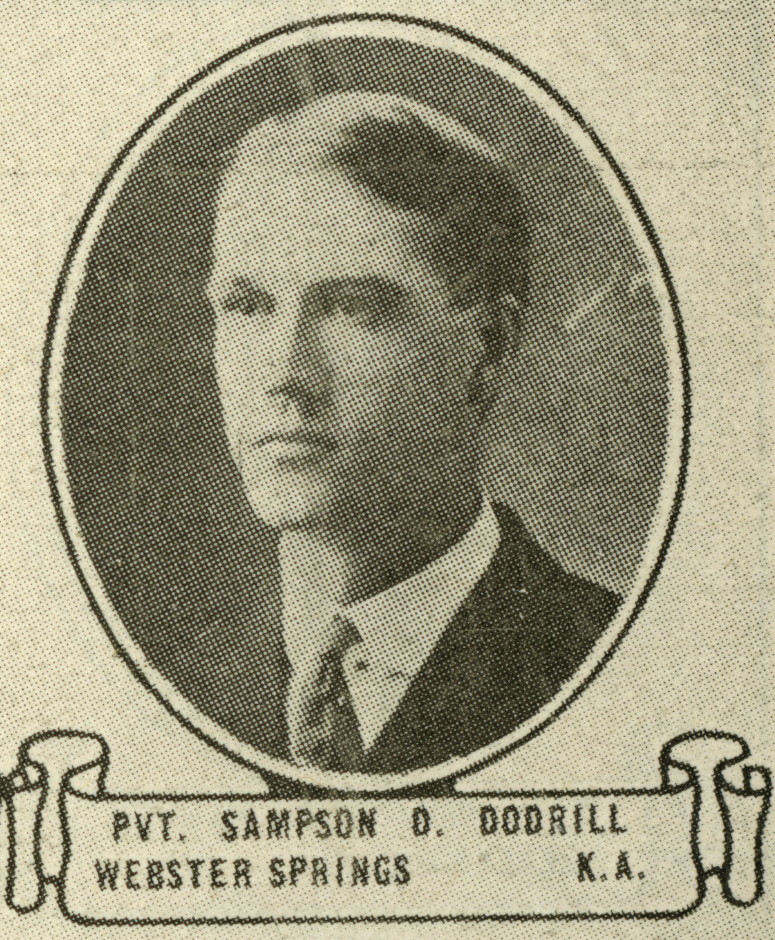

World War I exacted a high price on the Dodrill family. Four of John and Rebecca Dodrill’s five sons served in the US military. Not only did Sampson, as seen in this portrait, die of wounds on September 28, 1918 but his younger brother, Walker, died as well, two days earlier, on September 26, 1918 in Camp Lee, Virginia, of broncho pneumonia associated with influenza.19 Addison Rucker, the second oldest son, sailed with the 47th Provisional Company to France on August 22, 1918, and returned to the US on July 13, 1919.20 And on September 12, 1918, Hobart, the youngest of the four draft-age sons, was called to fight, returning home after the war to a devastated family.21

In 1922, the Veterans of the 314th Infantry Association bought, for fifty dollars, a log cabin which was originally a recreational quarters for military personnel at Camp Meade. They carefully transported it from Maryland to Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, in pieces via train car and restored it to create a memorial for the men who died in France. Valley Forge was specifically chosen because Pennsylvanians were the largest group at Camp Meade. In 2012, the Descendants and Friends of the 314th Infantry Association gave the log cabin back to Camp Meade where it serves as the Fort George G. Meade World War I Memorial. In the cabin, all the soldiers of the 314th infantry are memorialized on the bronze tablets. Each of the 361 soldiers who died in France, including Sampson Dodrill, are marked with a gold star, showing respect for the ultimate sacrifice they made.22 Sampson Dodrill is also remembered at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, France, where is his interred in Plot H, Row 21, Grave 30.23

Endnotes

1“1900 Federal Census,”database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed August 21, 2018), entry for Sampson Dolliver Dodrill; “1910 Federal Census” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed March 29, 2018), entry for Sampson Dolliver Dodrill; “United States World War I Draft Registration Card, 1917-1918” database, Ancestery.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed July 2, 2018) entry for Sampson Dolliver Dodrill.

2 Correspondence between Patsy Kiner Harper (Current Resident of Webster Springs) and Jonathan Foster, March 2018; West Virginia Department of Agriculture, Farm Land For Sale in West Virginia, 1915, Bulletin No. 2 (Charleston, West Virginia), 111-112 (https://books.google.com/books?id=BOwsAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA117&dq=West+Virginia+Department+of+Agriculture,+Farm+Land+For+Sale+in+West+Virginia,+1915,+Bulletin+No.+2+(Charleston,+West+Virginia)&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi0zqnIkNDdAhUUfn0KHZ8qClUQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=West%20Virginia%20Department%20of%20Agriculture%2C%20Farm%20Land%20For%20Sale%20in%20West%20Virginia%2C%201915%2C%20Bulletin%20No.%202%20(Charleston%2C%20West%20Virginia)&f=falseaccessed: September 3, 201).

3 Unfortunately, we cannot date precisely Sampson Dodrill’s arrival in Florida, we have only a time frame between 1910 and 1917. According to the 1910 federal census he was still registered as living with his parents in Webster Springs, West Virginia. By June 5, 1917, his home address was in Winter Park, according to his registration form for the draft. “1910 Federal Census,” Ancestry.com, Sampson Dolliver Dodrill; “United States World War I Draft Registration Card 1917-1918,” Ancestry.com, Sampson Dolliver Dodrill; “United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed September 3, 2018) entry for Rucker Dodrill; “United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed September 3, 2018) entry Walker B Dodrill.

4 “WWI Service Cards,” database, FloridaMemory.com, (https://www.floridamemory.com : accessed August 21, 2018) entry for Sampson Dolliver Dodrill.

5Army War College's Historical Section, Special Staff's Historical Division, Order of the Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War, vol 3 part 3 (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History United States Army, 1931), 745.

6 J. Frank Barber, History of the Seventy-Ninth Division A.E.F. During the World War: 1917-1919. (Lancaster, PA: Steinman & Steinman, n.d.), 37, (https://archive.org/details/historyofseventy0079th: accessed August 27, 2018).

7 Barber, History of the Seventy-Ninth Division, 39-40; "Passenger List of Organization and Casual." database, Fold3.com (http://Fold3.com: accessed March 12, 2018) entry for Sampson Dodrill Serial Number 2711953.

8 Roy M. Rentz, The 314th Infantry Regiment, 79th Division: The Men of the 314th Infantry Regiment in France, Comrades in WWI, Managing to Remain Comrades in Peacetime with Their Beloved Log Cabin as Their Rallying Point, vol. II (S.I.: S.n., 1995), 28; Barber, History of the Seventy-Ninth Division, 39-41.

9 Barber, History of the Seventy-Ninth Division, 45-47.

10 Barber, History of the Seventy-Ninth Division, 53-57; Army War College's Historical Section, Special Staff's Historical Division, Order of the Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War, vol 2 (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History United States Army, 1931), 322-323.

11 Jennifer D. Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 19.

12 Barber, History of the Seventy-Ninth Division, 129.

13 Edward G. Lengel, To Conquer Hell: The Meuse-Argonne, 1918, the Epic Battle that Ended the First World War, (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, 2008), 57.

14 Barber, History of the Seventy-Ninth Division, 59, 72, 75-127; Lengel, To Conquer Hell, 97-99.

15 Barber, History of the Seventy-Ninth Division, 110, 115, 120; Lengel, To Conquer Hell,125, 129.

16 Barber, History of the Seventy-Ninth Division, 122-124.

17 Barber, History of the Seventy-Ninth Division, 127.

18 Barber, History of the Seventy-Ninth Division, 144-146.

19 “Virginia, Death Records, 1912-2014”, database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed September 2, 2018) entry for Walker Dodrill.

20 “United States, Army transport Service Passenger Lists, 1910-1939” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed September 3, 2018) entries for Rucker Dodrill.

21 “United States, World War I Draft Registration Card,1917-1918” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed September 3, 2018) entry for Hobart Dodrill, “1920 United States Federal Census”, database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed September 2, 2018) entry for Hobart Dodrill.

22 “Log cabin Memorial - Veteran 314th Infantry Regiment A.E.F.”, The Descendants and Friends of the 314th Association (http://www.314th.org/: accessed September 24, 2018).

23 Sampson D. Dodrill,"Meuse Argonne American Cemetery”, American Battle Monuments Commission, (https://www.abmc.gov/node/339273#.W49YiuhKgcX: accessed April 25, 2018).

© 2018, University of Central Florida