Carl O. Anderson (March 3, 1893–October 3, 1918)

By Jordan Zeigler

Early Life

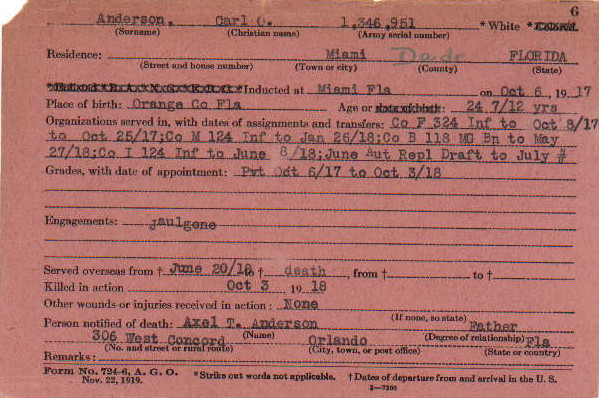

Carl Oscar Anderson was born on March 3, 1893 in Orange County, Florida. Anderson’s parents, Axel and Augusta Anderson, were Swedish immigrants who came to the United States in 1883, during a time when most Swedish immigrants to the United States came from rural areas. The family settled in Lake Maitland (today Maitland), where they purchased a farm. The Andersons had six children, three boys and three girls. Carl and his older brothers, Fred (1886) and Roy (1889), all attended school.1 Carl also had three younger sisters, Ida (1895), Annie (1898), and Alice (1902), who also went to school once they were old enough. By 1910, Carl's mother Augusta had likely passed away, and his older brother Roy still lived on the family farm, but worked as a fireman on the railroad.2 Particularly in Florida, Swedish migration (and moreover migration from the whole of Scandinavia) increased nearly ten-thousand percent between 1850 and 1930, with the apex of immigration occurring after 1870.3 George E. Pozzetta argues that after 1865, Florida needed to rebuild its population, as well as strengthen its agricultural, urban, and tourism industries. Rather than filling these occupations in a restructuring economy with African Americans, Pozzetta’s work demonstrates that Florida’s white leaders instead provided incentives for foreign-born Europeans to take these jobs in order to ensure that the white population remained at the center of Florida’s growth and prosperity.4 This anxiety over African American mobility paved the way for growing the number of European immigrants in the state of Florida, and is potentially an indirect reason the Andersons settled in Central Florida. Sometime around 1913, Anderson moved to Miami where he worked for the Melrose Dairy.5 While in Miami, he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917;6 he was formally inducted into the army on October 6, 1917.7

Military Service

Throughout his service, Anderson maintained the rank of private, serving in several units during his first eight months in the army.8 On June 20, 1918, Anderson was sent overseas, where he became a member of Company B, 30th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Division.9 Known as the “Rock of the Marne,” the 3rd Infantry Division gained this nickname during the Champagne-Marne Defensive at Château-Thierry, where they held a key position while under heavy German assault.10 According to Phillip St. John’s history of the 3rd Division, when the commander of the 3rd Division, General Joseph Dickman, received a concerned request from French command about whether they could hold the sector on July 15, he replied “Nous resterons là” (We will remain there).11 To this day, “Nous resterons là” is the American 3rd Division motto.

During the Champagne-Marne Defensive, Anderson was likely stationed with Company B in the outpost zone along the Marne River, on the southern edge of Château-Thierry.12 Shortly after midnight on July 15, the German 398th Infantry “overran the forward elements” of Anderson’s unit.13 Afterward, the 30th Regiment was relieved and instructed to follow the other regiments of the 3rd Division ten kilometers east toward Mézy. The 30th relieved the 38th on July 24, 1918, at which point Company B, of the 30th “took over the lines in and around Jaulgonne.”14 Anderson’s service card, pictured here, includes “jaulgone sic,” among his engagements, indicating his involvement in the portion of the battle that took place about eight miles east of Château-Thierry along the Marne River.15

After some time behind the lines, Anderson’s unit, much like the rest of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), fought in the Battle of Meuse-Argonne. From September 26 until the war ended on November 11, 1918, more than 26,000 Americans died of combat related wounds.16 Indeed, while fighting with his regiment during the early stages of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, Anderson was killed on October 3.17 On that day, the 30th rushed about seven miles north from the Bois de Montfaucon to the Bois de Beuge in order to support the 4th Infantry, where they faced shelling in their wooded position, and suffered heavy casualties.18 It is more than likely that Anderson died during this advance to Bois de Beuge. According to a December 1918 article in the Ocala Evening Star about his death in France, Anderson “wrote cheering letters to his father, brothers and sisters and they all were looking forward to the time for him to return, and then this message came which was a shock to them all.” Carl Anderson had been killed in action.19

Legacy

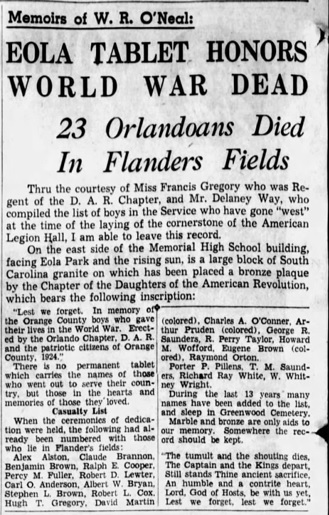

Anderson’s legacy remains in the memory of the local population. Anderson is one of twenty-three Central Floridians lost in World War I and commemorated on the Lake Eola Tablet. While no names appear on the tablet, an Orlando Sentinel article from its placement in 1924, pictured here, lists the names of all the men remembered in the city’s center.20 His sacrifice is also commemorated on the war memorial constructed outside the Orange County Courthouse, in the Central Florida Veterans Memorial Park at Lake Nona,21 and at the Montfaucon Monument in France.22 He is buried in Plot H, Row 4, Grave 9 at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, France.23

Endnotes

1 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed February 21, 2018), entry for Axel Anderson, Orange County, Florida; Lars Ljungmark, Swedish Exodus, trans. Kermit B. Westberg, (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1979): 27.

2 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed September 2, 2018). See Also “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed September 2, 2018).

3 Rhea M. Smith, “Racial Strains in Florida,” The Florida Historical Society Quarterly 11, no. 1(1932): 29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30150131.

4 George E. Pozzetta, “Foreigners in Florida: A Study of Immigration Promotion, 1865-1910,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 53, no. 2 (1974): 164, 166-167. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30149799.

5 “Killed in Action,” Ocala Evening Star, December 5, 1918, Newspapers.com.

6 “WWI Draft Registration Cards,” database, Fold3.com (https://fold3.com/: accessed February 15, 2018), entry for Carl O. Anderson.

7 “WWI Service Cards,” database, Florida Memory (https://floridamemory.com/: accessed February 13, 2018), entry for Carl O. Anderson.

8 “WWI Service Cards.”

9 “WWI Service Cards.”

10 Philip A. St. John, History of the Third Infantry Division (Paducah: Turner Publishing Company, 1994): 7.

11 St. John, Third Infantry Division, 7.

12 American Battle Monuments Commission, 3d Division, Summary of Operations in the World War, (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1944): 22. https://archive.org/stream/3dDivisionSummaryOfOperationsInTheWorldWar.

13 ABMC, 3d Division, 26.

14 ABMC, 3d Division, 40-42.

15 “WWI Service Cards.”

16 Jennifer D. Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011): 20.

17 “WWI Service Cards.”

18 Frederic Vinton Hemenway, History of the Third Division United States Army in the World War: For the Period, December 1, 1917, to January 1, 1919, (Andernach: M. Dumont Schauberg, 1919),143.

19 “Killed in Action,” Ocala Evening Star.

20 Winter Garden Prepares for Crowds Today,” The Orlando Sentinel, November 11, 1924, page 1, Newspapers.com; For list of names see also: “Eola Tablet Honors World War Dead,” The Orlando Sentinel, August 22, 1937, page 4, Newspapers.com.

21 “County Asks Help Tracing Veterans,” The Orlando Sentinel, January 23, 1997, page 64, Newspapers.com; “Orange County Commemorates Fallen Heroes at 2017 War Memorial Commemoration Ceremony,” Newsroom at Orange County Government Florida (Orlando, Florida), May 30, 2017, (https://newsroom.ocfl.net/2017/05/orange-county-commemorates-fallen-heroes-2017-war-memorial-commemoration-ceremony/: accessed April 18, 2018); “Veterans,” database, Central Florida Veterans Memorial Park at Lake Nona (http://veteransmemoriallakenona.org/: accessed April 18, 2018), entry for Carl O. Anderson. The Orange County Veterans Memorial was dedicated on November 11, 2013. On the Orange County Memorial, Carl’s name is misspelled as “Carol.”

22 For more about the Montfaucon Monument see: (https://www.abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials/europe/montfaucon-american-monument#.W1trhdhrwUQ: accessed July 27, 2018).

23 “ABMC Burials and Memorials,” database, American Battle Monuments Commission (https://www.abmc.gov/ : accessed April 17,2018), entry for Carl O. Anderson.

© 2018, University of Central Florida