John D. Watkins (February 22, 1889–December 8, 1918)

By Tess Pelaia

Early Life

John D. Watkins was born to James and Sarah Watkins on February 22, 1889 in Ocala, Florida.1 His Father, James, was born into slavery in 1859 and his mother Sarah, was born in 1865, the same year that the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished. James and Sarah were married in 1884. The couple had four children: Hattie (1885) the oldest, followed by Mamie (1886), John (1889), and James Jr. (1893).2 By 1900, the Watkins owned their home in Ocala, an opportunity afforded few African African Americans at the turn of the century.3 James worked as a farm laborer and Sarah kept busy by taking care of the house and her four children. John, eleven years old at the time, attended school along with three siblings, all of whom were literate.4

Despite rising from slavery to homeownership, and ensuring the education of their children, life in the Jim Crow South could not have been easy for the Watkins family. According to historian Jerrell Shofner, the black codes enacted after the end of the Civil War “established a separate class of citizenship for blacks, making them inferior to whites.”5 African Americans were subject to stricter laws and harsher punishments than whites who committed the same crimes. For example, an African American accused of burglary faced the death penalty. African Americans had become citizens after the Civil War, but by 1900, after the failure of Reconstruction, racial segregation became entrenched. Racist white southerners enacted harsh laws to enforce segregation, strip blacks of rights, and terrorize African-American communities. Laws passed in 1895 prohibited whites and blacks from attending the same schools or being taught by the same teachers. Because of this, African Americans, when they could, attended separate and unequal schools, especially in the South.6 In spite of this, it seems clear that the Watkins family valued education, as all the Watkins children went to school, where they learned to read and write, a valuable skill their parents knew would help improve their children’s lives.

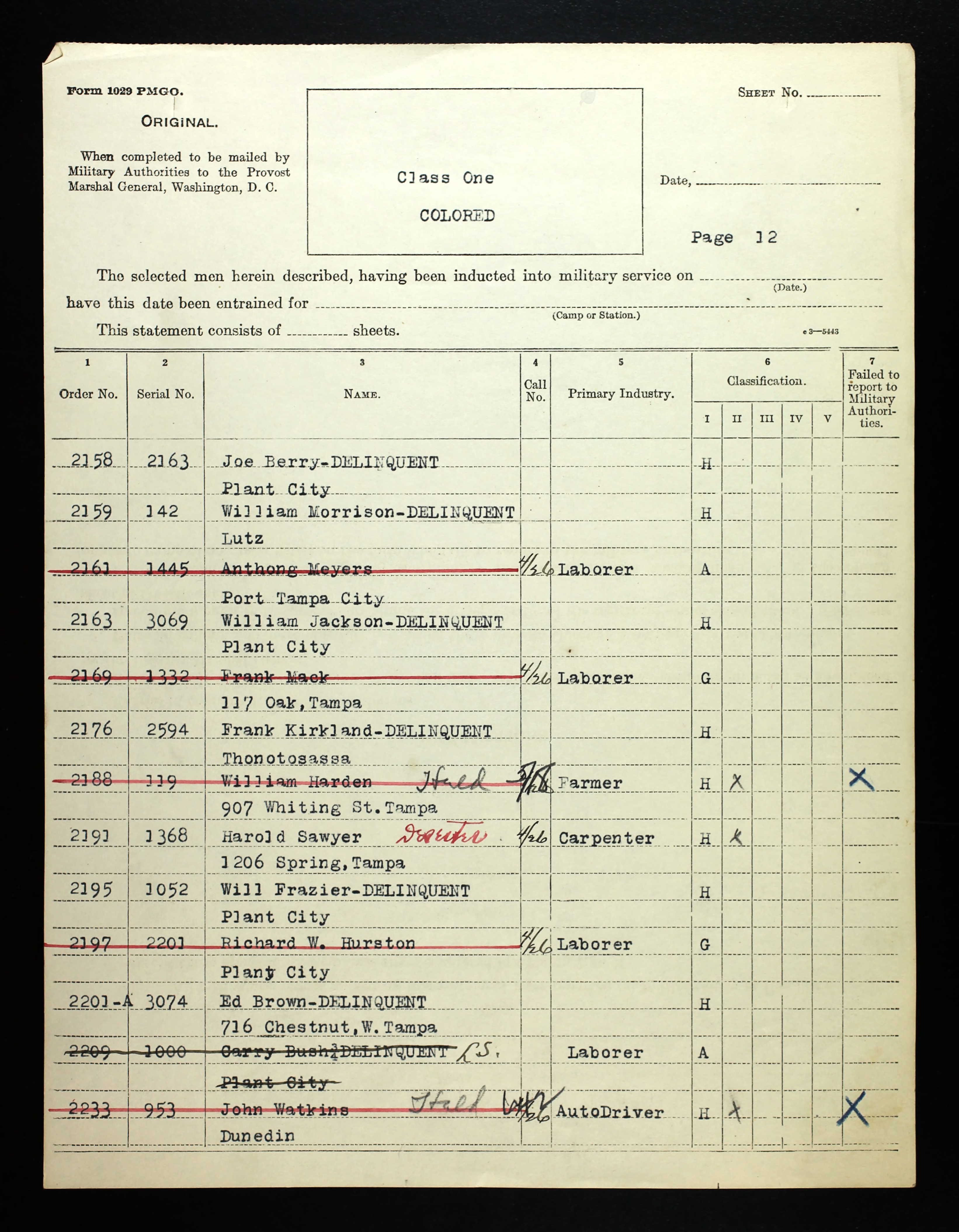

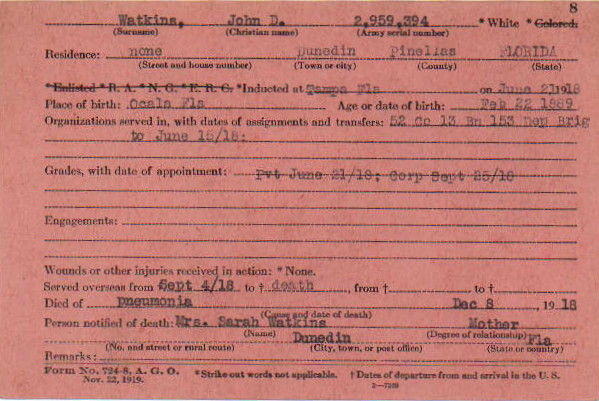

Before Watkins joined the US Army, he fell on hard times. His service card, pictured here, lists “none” for residence, which likely means he was homeless by 1918.7 The draft board, on the other hand, as pictured here, reported that he possessed a useful, rather rare skill; Watkins was an “Auto Driver.”8 During the Jim Crow era, African Americans could be punished for vagabondage – not having a fixed address. If convicted, the “vagrant” could post bond and be let go on the promise of good behavior, but if they could not post a bond, he or she was subjected to punishment by “pillory, whipping, prison, or by being sold for his labor up to one year to pay his fine and costs.”9 Every day that Watkins spent without an address he was in danger of strict punishment from the discriminatory law. Moreover, white draft boards often ensured that vagrant blacks ended up in military uniforms.10

Military Service

At age 29, on June 21, 1918, John D. Watkins was inducted into the U.S. Army in Tampa, Florida.11 The next month, Watkins relocated to Camp Dix, New Jersey as a Private in the 807th Pioneer Infantry, an all-black, segregated unit, organized in July 1918.12 On September 4, Watkins and the rest of the 807th shipped out from Hoboken, New Jersey, to France aboard the USS Siboney.13 It was originally built for the Ward Line as the SS Oriente, however, in 1917 the American government gained control of private ship building and altered the Ward Line’s ships to accommodate troop transport.14 The USS Siboney and its sister ship, USS Orizaba, were known as two of the best ships in troop transporting, traveling at speeds of over 17 knots while burning oil.15

Soon after arriving in France, on September 25, 1918, Watkins was promoted to the rank of corporal.16 He likely attained this promotion because he could read, write, and drive. He may have driven for a white officer who appreciated him and saw to his promotion. African Americans made up one third of the Army’s labor force, but they earned few promotions. 17Herbert Young, a fellow 807th soldier, remembered that they “went to the front and built bridges” with the French Army as the US Army “didn’t want us because we were colored.”18

The 807th supported and fought in the Meuse-Argonne campaign, the largest battle in US history, and a key part of the final Allied push to end the war.19 Though still officially serving in a non-combatant role, starting on October 25, 1918, John and his comrades leveled the ground for artillery and rebuilt transportation infrastructure damaged during the battle.20 The 807th served at the front without guns, as the US Army did not issue weapons to African Americans because of white fears about arming blacks.21 Their work on the front meant they faced poison gas attacks and met advancing Germans armed only with bayonets.22

Watkins was fortunate to survive the Meuse-Argonne campaign. After the war ended on November 11, 1918, Watkins and the other surviving members of the 807th remained in France, repairing infrastructure damaged over the course of the war and burying the dead.23 Less than a month after the war ended, he fell ill with the flu. The influenza epidemic of 1918 spread world wide at the end of the war. Twenty-six percent of the American Army fell ill with influenza over the course of the war, of those, one quarter developed complications, such as pneumonia. If a soldier contracted pneumonia they had a fifty percent chance of recovering. Black soldiers were admitted to hospitals less often than their white counterparts, on average one and a half black soldiers were admitted for every two white soldiers. Because of this, the death rate amongst African Americans was higher; in October 1918 five percent of ill African Americans died, while only three and one third percent of white soldiers did.24 Less than a month after the cease-fire, John D. Watkins died from pneumonia on December 8, 1918, in France.25 The US Army notified his mother, Sarah Watkins, of his death.26

Legacy

After the war ended, the 807th “was awarded the Silver Band to be engraved and placed upon the Pike of Colors of Lance of the Standard for its participation in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.”27 The silver band was awarded to any regiment for which half of the servicemen actively participated in that battle.28 The men from this regiment, both alive and dead, were held in high regard by the African American community. The black intellectual and civil rights leader, W.E.B. Du Bois described the men of the 807th as brave and cheerful, even when facing a short supply of rations and sleeping outside in the rain and mud.29 For DuBois, the men of the 807th had proven that black men were the equals of their white counterparts, noting that several soldiers from the unit were awarded the French Croix de Guerre for distinguished acts of bravery and that these men were a compliment to “their race.”30 John Watkins and the other men of the 807th honorably served the US, France, and the Allies; only about twelve of the three hundred and fifty men in the 807th Pioneer infantry unit made it back home to the US.31 Watkins now rests with over 14,000 other Americans in plot H, row 6, grave 23 at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, France.32

Endnotes

1 “World War I Service Cards,” database FloridaMemory.com (https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/227495 accessed February 2018).

2 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com/ accessed February 26, 2018). Entry for John D. Watkins, Marion County, Florida, Sheet Number 14, Family Number 277, Line 48.

3 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com. See also Leon F. Litwack, Trouble In Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1998) 128-130.

4 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com.

5 Jerrell H. Shofner, “Custom, Law, and History: The Enduring Influence of Florida’s ‘Black Code,’” The Florida Historical Quarterly 55, no. 3 (1977): 279. https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.net.ucf.edu/stable/30149151

6 Shofner, “Custom, Law, and History,” 279, 289-290.

7 “World War I Service Cards,” database FloridaMemory.com.

8 “U.S., List of Men Ordered to Report to Local Board for Military Duty, 1917–1918,” database Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com, accessed April 16, 2018), entry for John Watkins, Hillsborough, FL.

9 Shofner, “Custom, Law, and History,” 280.

10 Jennifer D. Keene, World War I The American Soldier Experience (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2006), 165-168.

11 “World War I Service Cards,” database FloridaMemory.com.

12 Robert J. Dalessandro, Gerald Torrence, Michael G. Knapp, Willing Patriots: Men of Color in the First World War (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Military History 2009), 56.

13 “US Army WWI Transport Service, Passenger Lists” database, Fold3.com (https://www.fold3.com/image/604170947, accessed March 1, 2018) and “US Army WWI Transport Service, Passenger Lists” database, Fold3.com. (https://www.fold3.com/image/604171084, accessed March 1, 2018). Also See Dalessandro, Torrence, and Knapp, Willing Patriots, 56.

14 Benedict Crowell and Robert Forrest Wilson, The Road to France II, Transportation of Troops and Military Supplies 1917-1918 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1921), 321.

15 Crowell and Wilson, The Road to France II, 321.

16 “World War I Service Cards,” database FloridaMemory.comp>

17 Keene, World War I, 171.

18 Eric Pace, “Herbert Young, Who Fought in World War I, Dies at 112,” New York Times (https://www.nytimes.com/1999/04/28/nyregion/herbert-young-who-fought-in-world-war-i-dies-at-112: April 28, 1999).

19 Dalessandro, Torrence, Knapp, Willing Patriots, 56.

20 United States. Army Corps of Engineers, 27th Regiment, Walter Renton Ingalls, History of the 27th Engineers, U.S.A. 1917-1919 (New York, 1920) 43, 47, 48.

21 Keene, World War I, 165.

22 Pace, “Herbert Young, Who Fought in World War I, Dies at 112.”

23 Dalessandro, Torrence, and Knapp, Willing Patriots, 56; Pace, “Herbert Young, Who Fought in World War I, Dies at 112.”

24 Keene, World War I, 165 and 101.

25 “World War I Service Cards,” database FloridaMemory.com.

26 “World War I Service Cards,” database FloridaMemory.com.

27 Dalessandro, Torrence, Knapp, Willing Patriots, 56.

28 United States. War Dept, Regulations for the Army of the United States, 1913: Corrected to April 15, 1917 (Washington Government Printing Office, 1918), 65.

29 W.E.B DuBois, “Return of the 807th Pioneer Regiment ca. 1919,” The W.E.B. DuBois Papers, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries (http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b219-i282: accessed April 22, 2018).

30 DuBois, “Return of the 807th Pioneer Regiment.”

31 Pace, “Herbert Young, Who Fought in World War I, Dies at 112.”

32 “John D. Watkins,” American Battle Monuments Commission, (https://www.abmc.gov/node/338687#WrqeN4jwY2y: accessed September 28, 2018).

© 2018, University of Central Florida