Andrew Jackson (May 16, 1893–November 4, 1937)

By Gerald Liles

Early Life

Andrew Jackson was born in Sparr, Florida, on May 16, 1893. Like so many of his fellow African American soldiers, Jackson’s pre-war life is difficult to track, partly because white Americans were less interested in documenting black lives. The 1900 Federal Census identified a seven-year-old Andrew Jackson living with his grandparents, Fate and Hennie Jackson,1 but he is listed as born in July of 1893, while he indicated May 16, 1893 as his birthday on his draft card. It may be a different Andrew Jackson, but with only 628 people in Sparr in 1900, (515 African Americans) it is also possible that Andrew’s grandparents could only recall that he was born in the summer.

Military Service

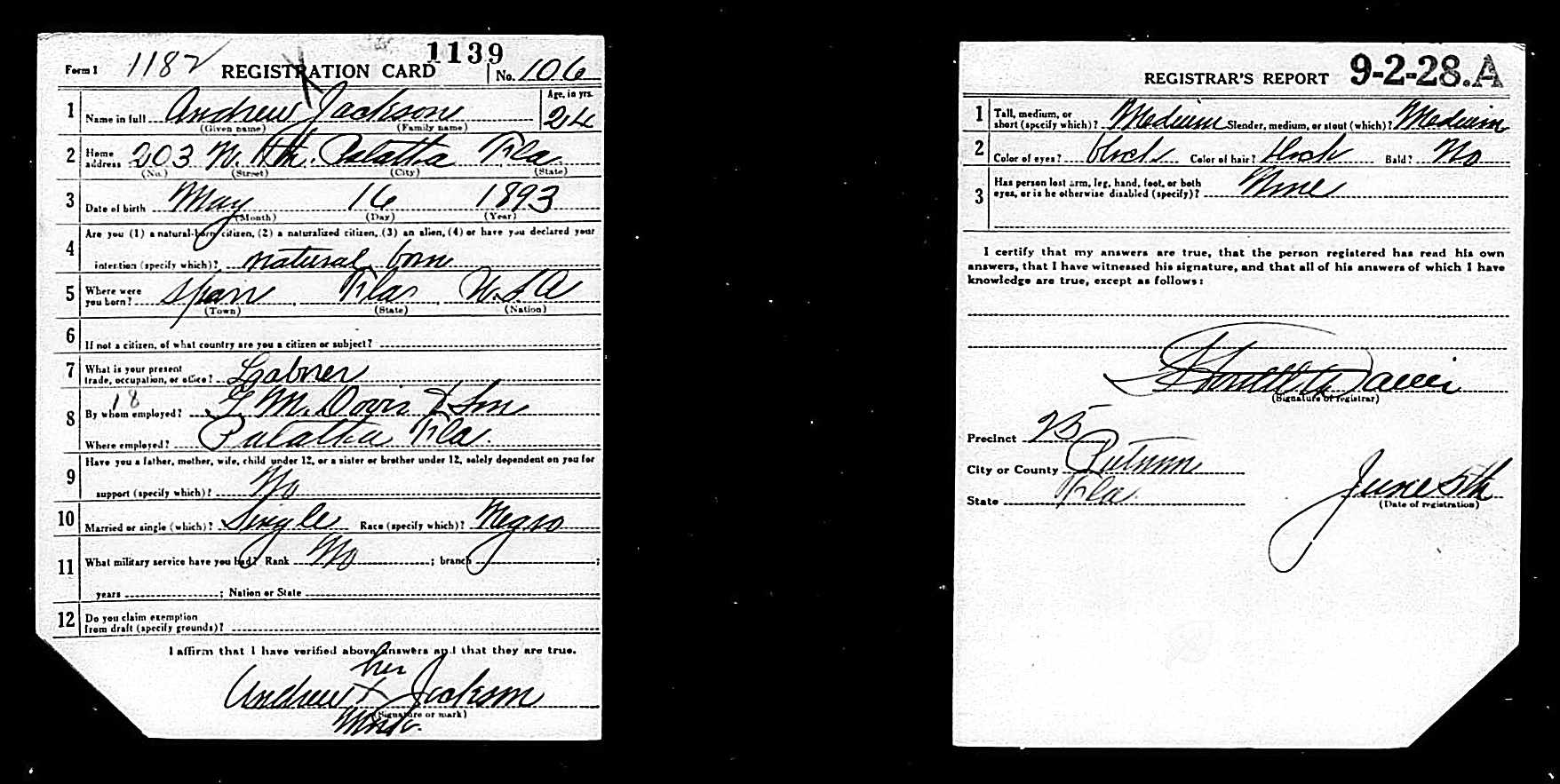

After the Selective Service Act of 1917 was passed, Jackson registered for the draft as shown here. Andrew’s draft card indicates that he may have lived in Sparr until he joined the military. At some point, Jackson moved to Palatka and was drafted into the Army in August of 1918. Before he joined the Army, he worked as a laborer for G.M. Davis and Son, a manufacturer of turpentine still tubs, i.e. cypress barrels, “from 100 to 100,000 gallons.” 2

He served as a private in Company M of the 807th Pioneer Infantry, with which he sailed to France in September of 1918 and returned the following July. The 807th took part in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the largest single battle in American history, with 1.2 million soldiers taking part.3 (By comparison, fewer than 200,000 soldiers total fought at Gettysburg and some 57,500 Americans took part in the D-Day invasion.) Pioneer infantry units were considered among the elite regiments for black troops. The unit consisted of white officers and black troops along with specialists such as mechanics and carpenters. Serving in a technical capacity, these regiments constructed and repaired roads, bridges, and railroads. While the Army did not consider pioneer infantry as combat units, their work on the front lines along with shifts in the lines of combat meant these units experienced direct action with the enemy. While many black soldiers felt slighted by having to perform these duties and face humiliation, mistreatment, and outright brutality, Underwood, as well as other black soldiers greatly contributed to the overall war effort. They continued to perform these duties after the armistice. 4

Post-Service Life

Jackson was discharged on July 9, 1919. After the war, he married Lucille Jackson, and together they had three children, William, Adele, and Alicia. He worked for the Florida East Coast Railroad all the way until his death on November 4, 1937, most likely laying rail; he is listed only as a “laborer.” 5

African American World War I veterans suffered a kind of patriotic betrayal, a rejection of their worth as soldiers and fellow citizens, that is far too obscure. It is inexcusable that far more Americans are familiar with George Washington honestly admitting to having cut down the cherry tree, which did not actually happen, than have ever even heard of the Red Summer of 1919, in which dozens of big cities and rural towns saw race riots remind blacks of their place in the racial hierarchy. The New York Times identified it as a national problem, and summarized several of the events, including one in Norfolk, Virginia: “Receptions of the homecoming negro troops had to be suspended because of riots July 21, in which six persons were shot, necessitating the calling out of the marines and sailors to assist the police.”6 The famous “Buffalo Soldiers” of the United States 10th Cavalry were attacked in Arizona.7 But the fact remains that while white veterans were celebrated and honored in myriad ways, some black veterans suffered violence for simply showing up in their uniforms at a veterans’ event in the white section of town.

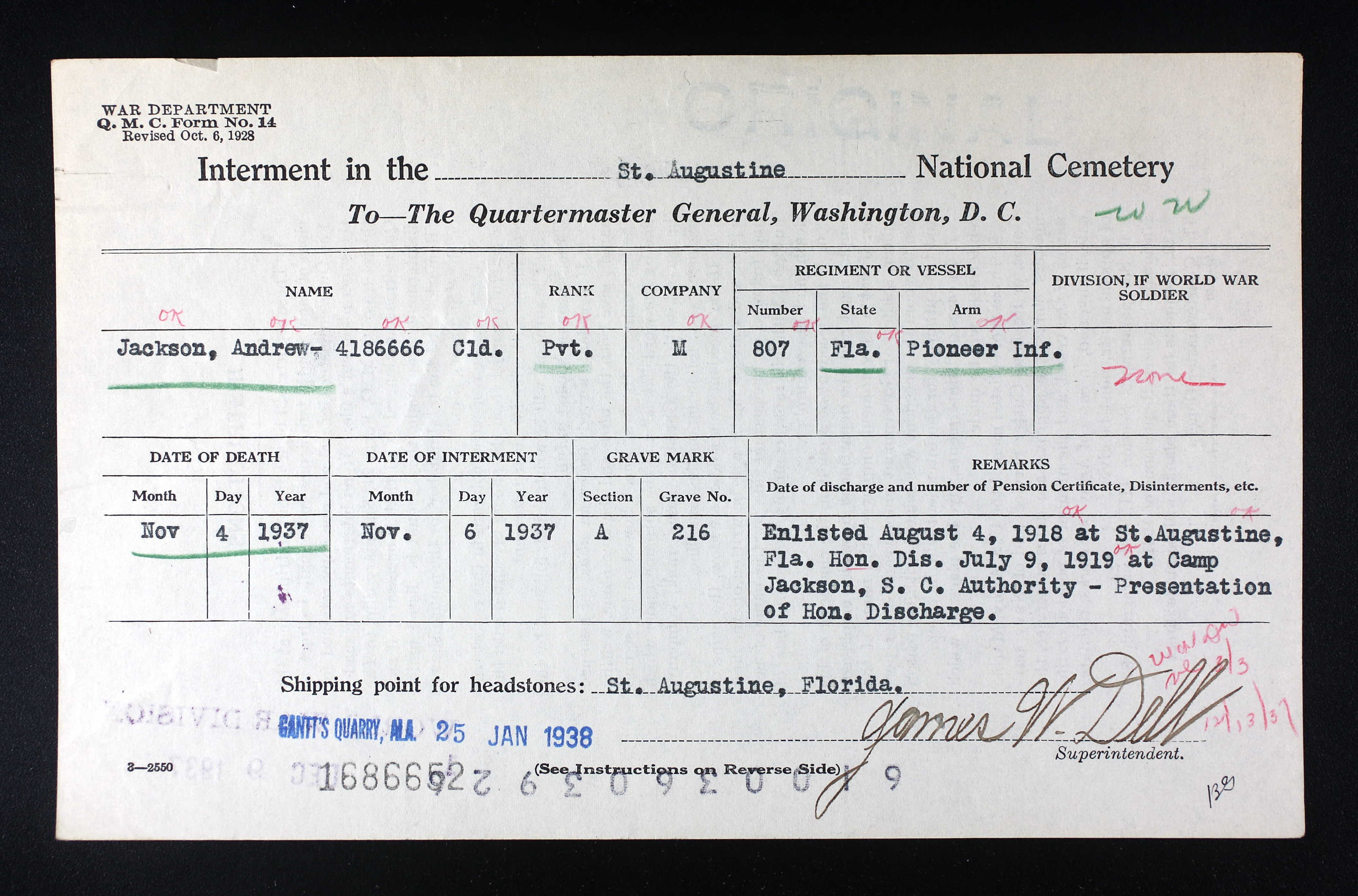

As shown here, Andrew Jackson died at the age of 44 of septicemic shock caused by an abscess tooth on November 4, 1937 and was interred on November 6, 1937 at Saint Augustine National Cemetery in Section A, Grave 216.8

Endnotes

1 Year: 1900; Census Place: Sparr, Marion, Florida; Page: 3; Enumeration District: 0095; FHL microfilm: 1240174.

2 “Cypress Tanks: From 100 to 100,000 gallons,” Advertisement for G. M. Davis and Sons, 1909.

3 Robert H Ferrell, America's Deadliest Battle: The Meuse Argonne, 1918 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007).

4 Derrel B. Depasse, Traveling the Rainbow: The Life and Art of Joseph E. Yoakum (New York/Jackson, MS: Museum of American Folk Art/University Press of Mississippi: 2001), 11; Tammy M. Proctor, Civilians in a World at War: 1914-1918 (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 56.

5Year: 1930; Census Place: St. Augustine, Florida; Page: St. Johns County; Enumeration District: 13;

NARA, T626 roll 332.

6 “For Action on Race Riot Peril: Radical Propaganda Among Negroes Growing, and Increase of Mob Violence Set Out in Senate Brief for Federal Inquiry The War's Responsibility. Reds Inflaming Blacks. Industrial Clashes. I. The Facts--1919. II. The Failure of the States. III. A National Problem. IV. Consequences of Lynching. V. The Danger.” New York Times, October 5, 1919. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1919/10/05/106999010.pdf Accessed August 9, 2018.

7 Ibid.

8Andrew Jackson in U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962, Database, Ancestry.com. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

© 2018, University of Central Florida