Chief Heap of Birds / Many Magpies

By Abbyahna Wade

Early Life of Chief Heap of Birds

Chief Mo-e-yau-hay-ist or Heap of Birds1 Many Magpies2 was born in the mid-1800s in the heart of the Plains territory, which spanned parts of modern-day Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and the Dakotas. Little is known about his parents, due to very little oral history having been retained regarding his ancestral family. From an early age, Heap of Birds was raised learning the traditions and responsibilities of Cheyenne culture. Being taught the responsibilities of a young Indigenous warrior to better provide for the community, continue traditions, and protect the women and children of the tribe, he would be taught how to hunt, fight, and carry on the culture through oral tradition alone.3 His upbringing would prepare him for the later hardships of life on the Plains, including tribal conflicts, the harsh nature of the Plains themselves, and the ever-encroaching threat of the Western world.4

Following his upbringing, Heap of Birds would go on to wed multiple brides, but only one would continue his legacy by bearing his children, ‘Red Painting Woman’.5 Soon after the birth of his children, a tragic event known as the Sand Creek Massacre occurred—a brutal attack on the peaceful encampment of the Cheyenne and Arapaho people.6 This atrocity was ultimately driven by the ideology of “Manifest Destiny,” which played a significant role in the violence.7 Following the massacre, many survivors, one of whom was believed to be Heap of Birds, were taken prisoner, and transported to Fort Sill where the start of his mistreatment would unfold.

Incarceration Period

Shortly after his capture in 1875, Heap Of Birds and the other captives were prosecuted under trumped-up charges.8 They were labeled by the United States government as ringleaders of criminal organizations, and transported to Fort Sill.9 Along with the other survivors of the Plains conflicts, his journey to Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, would begin whereupon he would experience some of the most cruel and unusual punishment in American History. While on the journey the captives were paraded through town, from one settlement to the next, used as a traveling attraction for locals to gawk at to help line the pockets of the soldiers.10 One of the worst things they experienced, was emasculation, which to a young Indigenous warrior, was the breaking down of one’s dignity and personality.11 Seventy-four of them were gathered, amongst them were headsmen, chiefs, warriors, medicine men, one woman, and one child. Shackled together at the hands and feet, Heap of Birds was thrown into the backs of wagons, trains, and steamboats for varying lengths of the journey to Fort Marion.12 This however was just the beginning of what was to come. Upon his arrival at Fort Marion, he and the other captives were housed in a small room with nothing to sit or sleep on beside the cold dirt floor. He would be insulted, beaten, and broken down during this period.13 Perhaps preparing him for what was to come these days would be difficult but numbered. Six months after their arrival, a lieutenant by the name of Richard Henry Pratt would be assigned to take the reins of the prison where he would conduct his own private reformation and re-education experiments with the captives.14

Upon arrival, Lt. Pratt would command the guards to remove the shackles, a seemingly kind act at first but later it was obvious the shackles were only removed to accommodate for the intense labor, and other atrocities Heap of Birds among other captives would be subjected to. Another one of Pratts’s acts was to have the heads of the prisoners forcefully cast in plaster for future scientific study, their justification for such a horrific act was their belief the Indigenous people would soon be extinct. During the process, their heads were completely encased in a mold while they took labored breaths through straws shoved up their noses.15 Heap of Birds and the other captives were given the materials needed for the construction under the guise of being given new housing, they of course had to build themselves. Once settled into their newly constructed housing they would begin their reeducation. Replacing the current guards at the fort, Heap of Birds among other men, would be forced to wear military uniforms, learn English, carry out daily drill practices, and exercise routines. The guards at Fort Marion would be completely replaced by the prisoners. Along with his new regiments, Heap of Birds was also taken camping on nearby Anastasia Island where he and other prisoners would be taught how to sail boats and hunt fish, a skill not known to tribes of the Great Plains.16 On the island sat a lighthouse many of the prisoners looked upon each night longingly, many of them would draw the same lighthouse in their ledgers. Many of these drawings among others would be sold for profit by Pratt. Drawings however were not the only thing sold for profit, labor was too, long unpaid shifts working odd jobs were a regular occurrence. Perhaps the most humiliating and degrading thing forced upon them were the shows and events regularly hosted and approved by Pratt, wherein prisoners would be forced to sing, dance, and act for the amusement of the local townsfolk.17 During the time spent at Fort Marion, many of the prisoners would ‘write’ to their families, one of whom was Heap of Birds. Records of the correspondence between the prisoners and Pratt’s men show Heap of Birds supposedly wrote,

Tell my family I am well, and Capt Pratt is along with me yet, and I am all right; they must not cry or mourn for me, but have strong hearts. I feel good every day and with the young men am trying to pick up this white man’s road. I think the President will turn me back some day and will let me learn to live in peace. Tell the Agent I want my children to go to school. I told the Agent once before but have not heard whether they are in school or not.18

This letter stands in contrast to what his descendant’s believe. He would continue to live at the fort for two years.

Legacy

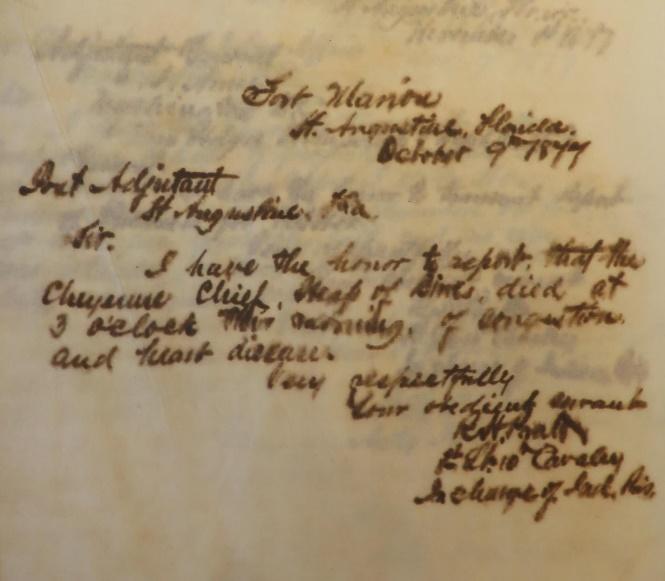

Heap of Birds would go on to endure many other atrocities aside from the ones listed, but he would sadly meet the end of his days within the confines of the prison. On October 9th, 1877, Captain Pratt would deliver the news in a letter to his superiors that Chief Heap of Birds had passed.19 It is speculated that he died from tuberculosis. However, he left behind multiple legacies. During his marriage to Red Painting Woman, he fathered three boys who would go on to father children of their own. His sons would be named Alfrich Heap of Birds, Homer Heap of Birds, and Howling Water. 20 Alfrich Heap of Birds was born on March 13, 1869. 21 Alfrich would attend Carlisle Boarding School from 1880 until 1883. Following his departure from the school, he returned home to Clinton, Oklahoma to farm.22 He would marry Soar Woman (Grace Big Bear), and they would welcome 6 children together, John Heap of Birds (Many Magpies), Ruth Heap of Birds (Owlet Woman), Esther Heap of Birds (Red Paint Woman), Guy Heap of Birds (Howling Water), Helen Heap of Birds (Blue Wing), and Sarah Heap of Birds.23 Homer Heap of Birds was born in what would be present-day Oklahoma on June 30, 1866. He would go on to marry Little Woman. 24 It is unknown if he had children. He would also join the military in 1888 in Clinton, Oklahoma. 25 Homer would die in 1940 and be buried in the Clinton Indian Cemetery of Custer County, Oklahoma. 26 There is not much known about his third son Howling Water.27 While Chief Heap of Birds would not, his legacy would go on to live past the confines of the Fort. His family continues to thrive today and flourish all over America.

Endnotes

1 Madeleine Mulford, “UCF Researchers Help Restore the Lost History of Indigenous Prisoners in St. Augustine | University of Central Florida News.” University of Central Florida News | UCF Today, January 30, 2023. https://www.ucf.edu/news/ucf-researchers-help-restore-the-lost-history-of-indigenous-prisoners-in-st-augustine/.

2 Moses Starr Jr., interview by Abbyahna Wade, Oklahoma, July 12, 2024.

3 Pauls, E. Prine. "Plains Indian." Encyclopedia Britannica, September 4, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Plains-Indian.

4 Agatha Starr, “Starr undated family tree,” in family papers of Agatha Starr, Weatherford, Oklahoma.

5 Agatha Starr, “Starr undated family tree,” in family papers of Agatha Starr, Weatherford, Oklahoma.

6 National Park Service, “The Sand Creek Massacre- Castillo de San Marcos,” May 21, 2020, accessed July 30, 2024, https://home.nps.gov/casa/learn/historyculture/the-sand-creek-massacre.htm.

7 It was during this period of removal of the Native American Plains tribes and bands from their ancestral homelands that the United States Army forced them to move onto reservations. It was thought by the US government officials at the time that removing the headmen and warriors from their families would force the rest of the tribes to comply with the US government.

8 “Synopsis showing names of Indian Prisoners and charges against them.” Richard Henry Pratt Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University (WA MSS S-1174, Box 23b, f. 751a).

9 Ibid.

10 National Park Service. “Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche & Caddo Incarceration,” June 6, 2024. Accessed June 20, 2024. https://www.nps.gov/casa/learn/historyculture/plains-incarceration.htm.

11 Agatha Starr, interview by Abbyahna Wade, Oklahoma, August 8, 2024.

12 National Park Service. “Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche & Caddo Incarceration,” June 6, 2024. Accessed June 20, 2024. https://www.nps.gov/casa/learn/historyculture/plains-incarceration.htm.

13 Agatha Starr, “Starr undated family tree,” in family papers of Agatha Starr, Weatherford, Oklahoma.

14 National Park Service. “Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche & Caddo Incarceration,” June 6, 2024. Accessed June 20, 2024. https://www.nps.gov/casa/learn/historyculture/plains-incarceration.htm.

15 Michael Lauricella, “Ghosts of the Peabody: The Fort Marion Life Casts,” The Harvard Crimson, March 10, 2016, accessed July 10, 2024, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2016/3/10/peabody-life-casts/.

16 National Park Service. “Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche & Caddo Incarceration,” June 6, 2024. Accessed June 20, 2024. https://www.nps.gov/casa/learn/historyculture/plains-incarceration.htm.

17 National Park Service, “Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanche & Caddo Incarceration.”

18 Richard Henry Pratt, “Pratt to Miles, 3 January 1876,” Oklahoma Historical Society.

19 Richard Henry Pratt, “Letter Informing of Heap of Birds Death” January 3, 1876.

20 Agatha Starr, “Starr undated family tree,” in family papers of Agatha Starr, Weatherford, Oklahoma.

21 Ancestry.com. U.S., Find a Grave® Index, 1600s-Current, database on-line. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

22 Alfrich Heap-of-Birds Student File, Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center. Alfrich Heap-of-Birds Student File | Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center (dickinson.edu)

23 Susan Hiller, ed., The Myth of Primitivism: Perspectives on Art (New York: Routlege, 2005), 292.

24 Ancestry.com. “U.S., Indian Census Rolls, 1885-1940 Online,” Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com 2007. Accessed July 15, 2024.

25 Ancestry.com. “U.S., Veterans Administration Master Index, 1917-1940,” Lehi, UT. USA: Ancestry.com, 2019, accessed July 15, 2024.

26 “Alfrich Heap-of-Birds I Family Tree,” Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com, 2012, accessed July 15, 2024.

27 Agatha Starr, “Starr undated family tree,” in family papers of Agatha Starr, Weatherford, Oklahoma.

© 2024, University of Central Florida