Harold Everett Rake (September 16, 1915–December 25, 1944)

Company L, 142nd Infantry Regiment, 36th Infantry Division

By Jillian Rodriguez and Luci Meier

Early Life

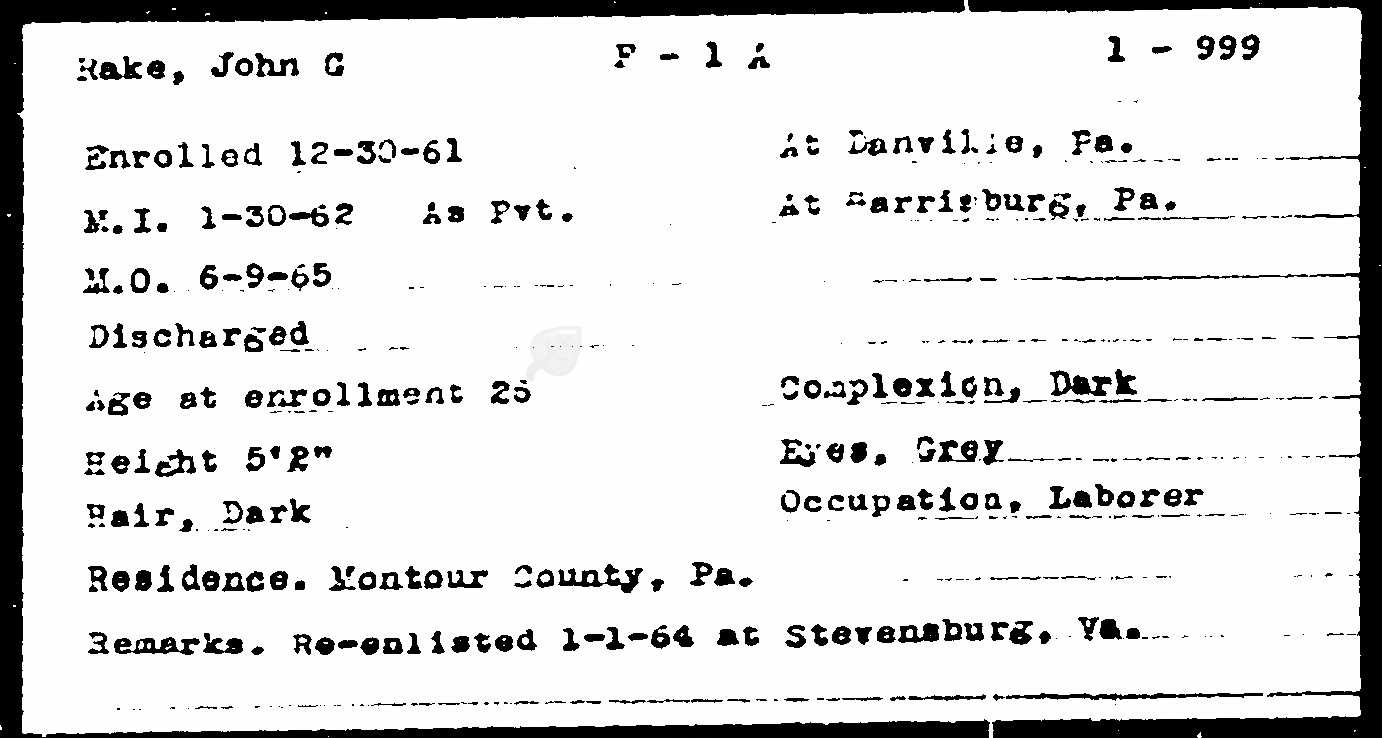

Harold Everett Rake was born on September 16, 1915, in St. Augustine, St. Johns County, FL.1 Harold’s family lived in Florida for at least two generations before his birth. All but one of his grandparents were born in the state.2 His paternal grandfather, John Gayhart Rake, was originally born in Pennsylvania, and served as part of Battery F, 1st Pennsylvania Regiment, Light Artillery in the Union Army during the American Civil War, seen here.3 This unit participated in a number of significant battles during the conflict, including the Battle of Gettysburg in early July, 1863.4 In the years following the war, John Gayhart Rake moved to Florida, married Anna Reyes in 1878, and started a family in St. Johns County.5 Both of Harold’s parents, John Henry (John Gayhart’s son) and Martha “Mattie” Rake, were also born in Florida and raised in St. Johns County.6 The second of John Henry and Mattie’s six children, Harold grew up with one older sister, Flossie (born 1914), and four younger siblings: three brothers, Earl Otis (born 1919), Wallace Rudolph (born 1923), and Clark Eugene (born 1924), and one sister, Adelaide Winifred (born 1921).7 Growing up, the family stayed close to relatives as all of Harold’s grandparents also resided in St. Augustine.8

Harold attended school through the eighth grade.9 In 1940, less than half of the adult US population had completed more than an eighth grade education. The Great Depression, which began after the stock market crashed in October 1929, greatly affected education rates across the country, as school-age teenagers often dropped out to provide extra income for the family.10 Harold likely did not continue his schooling so that he could instead contribute additional income to support his family of eight. The Rake siblings all shared a similar educational background, opting to join the workforce rather than complete high school. For example, in 1935 Harold’s sister Flossie worked as a caretaker, and in 1940 his younger brother Earl worked as a clam digger in the fishing industry in St. Augustine.11

The Rake family remained in St. Augustine throughout the 1930s and 1940s; however, the economic realities of the time forced them to frequently move around rented homes. In 1930, the family lived in a rented house on Ocean Blvd, about four miles north of St. Augustine’s historic center.12 In 1940, they lived in a different rented home in an unincorporated area of St. Johns County.13 Harold’s father John Henry also faced uncertainty and instability regarding his source of income. He worked in several industries throughout the Depression years, variously supporting his family as a railroad carpenter, a truck driver, and a clam digger, while his wife Mattie maintained the home and raised the children through these difficult times.14

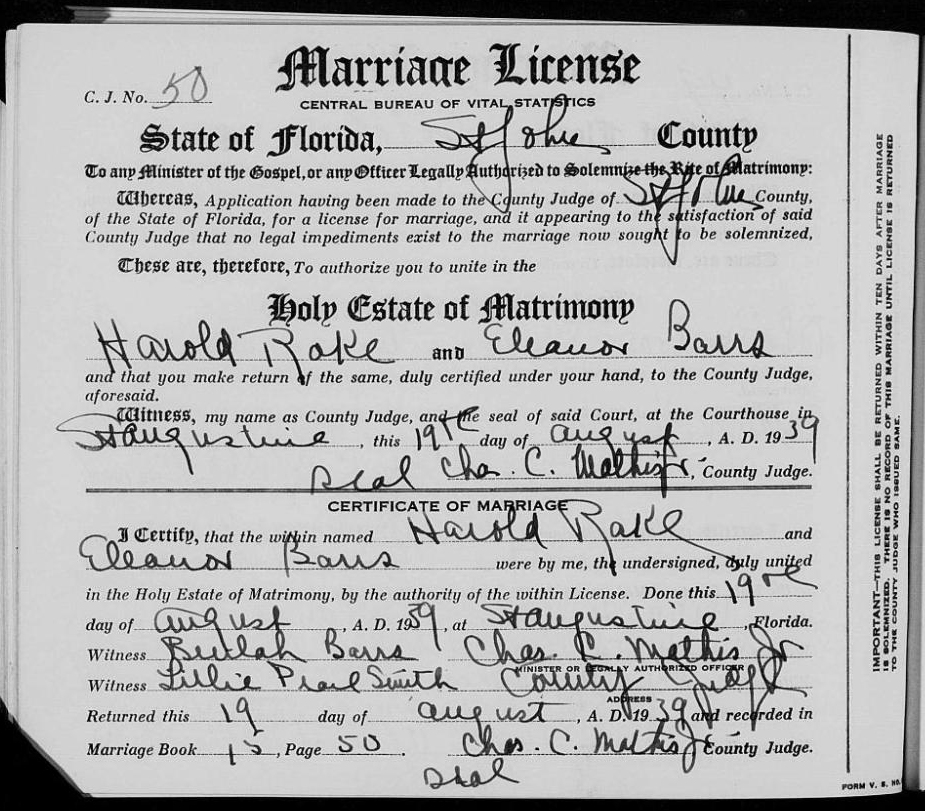

By 1940, the Rake household consisted of parents John Henry and Mattie, and Harold’s three younger brothers Earl, Wallace, and Clark.15 Harold’s older sister Flossie married Alfred P. Cyr, a truck driver from Miami, in 1936, and his younger sister Adelaide married Luther Stewart, a farm hand in St. Johns County, in 1939.16 On August 19, 1939, Harold married Eleanor Barrs in St. Augustine, noted here.17 The newlyweds settled in Brevard County, where Harold worked for the State Road Department as a dragline operator.18 Dragline operators work heavy machinery to clear earth for land and road development. In the years following their marriage, Harold and Eleanor welcomed three kids together: James Harold (born 1939), Betty Jean (born 1942), and Janice Carol (born 1943).19

Military Service

Harold’s paternal grandfather John Gayhart Rake, who fought in the American Civil War, began a legacy of military service that many future Rake men followed. Harold’s uncle George Rake served in the Army during World War I as part of Battery F, 118th Field Artillery Regiment, 31st Division. George served overseas during the final months of the war, returning to the US aboard the UST Martha Washington from Brest, France in December, 1918.20 On October 16, 1940, at twenty-five years old, Harold officially registered for the draft in Brevard County, FL. His twenty-one-year-old brother, Earl, registered on the same day in St. Augustine.21

Keeping with the family’s strong tradition of military service, Harold and all three of his brothers enlisted for duty during World War II. Earl enlisted in the Army on February 26, 1942, Wallace on February 26, 1943, and Clark on March 13, 1943.22 Wallace and Clark both enlisted at Camp Blanding, FL, where Wallace also worked prior to his enlistment in the Army.23 On December 31, 1943, Harold joined his brothers and enlisted in the US Army at Camp Blanding.24 Acquired by the Florida National Guard in 1939 and federalized in 1940 for use by the US Army, Camp Blanding served as a training center, and throughout the early 1940s expanded to accommodate more troops as the US prepared to join the war overseas. Throughout the war years, Camp Blanding variously constituted an induction site for new recruits, an Infantry Replacement Training Center, and a holding site for German and Italian prisoners-of-war.25 Harold’s father, John Henry, worked at Camp Blanding as a carpenter during the time his sons enlisted, suggesting further associations between the Rakes and the US military.26 As a carpenter, John Henry likely played a role in Camp Blanding’s expansion as the nation mobilized to enter the Second World War.27

Harold served as a Private in the US Army as part of Company L, 142nd Infantry Regiment, 36th Infantry Division (ID).28 As part of the 36th ID, Harold participated in the Italian and French campaigns of World War II. The 36th ID originally departed from New York for North Africa on April 1, 1943. They then participated in the Allied invasion of Italy, which began at Salerno, on the country’s eastern coast, on September 9.29 In January 1944, the 36th ID attempted to cross the Rapido River, about eighty-five miles south of Rome, in an effort to break Germany’s Gustav Line, a series of military defenses that ran from coast to coast across the Italian Peninsula. German forces fought back with strong opposition and the 36th ID suffered major casualties. While their efforts did not achieve the hoped-for results right away, the division successfully aided in distracting enemy combatants from the Allied landings at Anzio, a coastal town thirty-five miles southwest of Rome. The Anzio beachhead landings allowed the Allies closer access to Rome, and aimed to cut enemy communication and supply lines and recapture the city from German control. On May 22, 1944, the 36th ID landed at Anzio to reinforce the beachhead established by the Allies. Given that Harold enlisted on December 31, 1943, he likely joined the 36th ID as a replacement around this time. Over the next month, these troops fought toward Rome, finally liberating the city from German forces in June 1944.30

The Allies initially planned two invasions of France in the Spring and Summer of 1944. Operation Overlord, the invasion of northern France, occurred on June 6, 1944, with the landing of Allied forces in Normandy. Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France, commenced in August 1944. Allied leaders believed that engaging German troops from both the north and the south would weaken the German forces. The Allies, however, could not obtain the supplies needed to make simultaneous invasions.31 Therefore, on August 15, 1944, the 36th ID, along with other American and French troops, landed near the southern port cities of Marseille and Toulon.32 The 36th ID advanced to seize St. Raphael, a small port town in southeastern France. Though met with German opposition, the successful landings here provided the Allies with additional locations from which to deploy American troops for continued offensives farther east across the European continent.

Through the Autumn of 1944, Harold and his division progressed up the Rhone River Valley in a race to block the German retreat back toward the Vosges Mountains along the French-German border. On November 25, 1944, the 36th ID finally reached the Alsatian Plains.33 There, they encountered German counterattacks in an area known as the Colmar Pocket, one of Germany’s last French strongholds in central Alsace.34 Harold and his unit made slow progress through this area in early December, as the Germans mounted nearly constant counteroffensives. The 36th ID, exhausted after almost continual fighting since they crossed the Vosges Mountains in October, faced some of the heaviest artillery combat of the war during this time. Finally, on December 15, Major General John E. Dahlquist, commanding officer of the 36th ID, requested the unit be pulled off the line for rest. Harold and his comrades then entered reserve status.35 Along with combat maneuvers, soldiers also perform important, dangerous, and heroic actions to prepare for further battle when in this reserve status. While getting ready to continue the fight against the Germans in eastern France, Harold made the ultimate sacrifice when a train struck and killed him.36 Harold Everett Rake died of non-battle related injuries sustained in this incident on December 25, 1944.37

Legacy

As the Second World War stretched into 1945, the 36th ID continued the Allied fight, facing resistance as it reentered combat and crossed the Rhine into Germany that March.38 As the division made its way south into the Bavarian Alps through April, it encountered and liberated several concentration subcamps in Kaufering, attached to the larger concentration camp in Dachau, a town about ten miles northwest of Munich.39 The Nazis utilized forced labor at these subcamps to increase weapons production and to hollow out mountain sides to construct underground factories and systems of tunnels protected from Allied bombings.40 In 1995, fifty years after the end of the war, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the US Army’s Center of Military History jointly recognized the 36th ID as a liberating unit for its role in securing these camps on April 30, 1945.41 The 36th ID remains a significant World War II unit for these reasons and others. Along with its liberating actions, the 36th ID accepted the surrender of Nazi Field Marshal Hermann Goering in the closing days of the war, saw seventeen of its members earn the Medal of Honor, and received twelve Distinguished Unit Citations for its participation in five Campaigns during World War II.42

Though Harold did not return from service, his family back home in the US continued his legacy. Eleanor, widowed by the premature passing of her husband, raised her and Harold’s three children, James, Betty, and Carol. They continued to live in Florida, but by 1945 had moved to Putnam County.43 By 1950, Eleanor had remarried to Van Scott, a furniture manufacturer, and had three more children: Robert, Dorothy, and Jeffie.44 Eleanor passed away in 2011 at the age of eighty-eight, nearly seven decades after her husband Harold died in Europe. She now rests with him in St. Augustine National Cemetery.45

Much of Harold’s family remained in Florida after his death. His parents continued to live in St. Johns County. His father, John Henry, worked as a watchman for the state road department in 1950.46 At the time, Harold’s parents lived on the same street as his brothers Earl and Wallace and their growing families. After their service, Earl and Wallace both worked as mechanics.47 In 1950, Harold’s sister Flossie lived in Dade County, FL with her husband Alfred and their three children, Alfred, Jr., Martha, and Cecilia.48 His other sister Adelaide still resided in St. Johns County. She and her husband, Luther, lived with their son, Luther, Jr., in Leonard Farms Tenant Houses, where Luther worked as a farm hand.49 Clark, Harold’s only sibling to move out of Florida, continued his military service. He moved to Fort Hood, TX with his wife and children.50 Clark served in Korea with the 555th Field Artillery, commonly known as a “Triple Nickel” unit.51 The term ‘Triple Nickel’ refers to the unit’s numerical identifier, which consists of three fives. For his service, Clark earned three Bronze Stars.52

Harold was originally buried in the American Epinal Cemetery in eastern France. In August 1949, the US military reinterred his remains in St. Augustine National Cemetery, where he now rests in Section B, Plot 570.53 At the time of his reburial, he joined his grandfather, John Gayhart Rake; his grandmother, Annie Rake; and his uncle, George Rake at the cemetery. Three years later, in 1952, Harold’s brother Clark passed away at Walter Reed Army Hospital after an unfortunate traffic accident.54 He now also rests alongside his family in St. Augustine National Cemetery.55 With three generations of American servicemen spanning the Civil War, World War I, World War II, and the Korean War buried in one national cemetery, the Rake family holds a unique legacy, not only in the armed forces, but also in St. Augustine, FL.

Endnotes

1 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 17, 2024), entry for Harold E. Rake; “Harold Everett Rake,” FindAGrave, March 13, 2000, accessed April 21, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/3964991/harold-everett-rake.

2 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Henry J. Rake, St. Johns County, FL; “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Martha Miller, St. Johns County, FL.

3 “U.S., Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for John G Rake.

4 “Battle Unit Details: Union Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1st Regiment, Pennsylvania Light Artillery (14th Reserves),” National Park Service, accessed May 17, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=UPA0001RAL.

5 “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 29, 2024), entry for John Rake and Anna Reyes; “1880 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 17, 2024), entry for John Rake, St. Johns County, FL.

6 “1900 United States Federal Census,” entry for Henry J Rake; “1910 United States Federal Census,” entry for Martha Miller.

7 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for J.H. Rake, St. Johns County, FL; “Harold Everett Rake,” FindAGrave.

8 “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for John W Miller, St. Johns County, FL; “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Annie J Rake, St. Johns County, FL.

9 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Harold Rake, Cocoa, Brevard County, FL.

10 120 Years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait, ed. Thomas D. Snyder (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, US Department of Education Office of Educational Research and Improvement, 1993), 7, https://nces.ed.gov/pubs93/93442.pdf.

11 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for John Rake, St Johns County, FL; “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Flossie Cyr, Miami, Dade County, FL; “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for John Rake, St Johns County, FL.

12 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 17, 2024), entry for Mattie Rake, St. Johns County, FL.

13 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 17, 2024), entry for Mattie Rake, St. Johns County, FL.

14 “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Harold Rake, St Johns County, FL; “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Harold Rake, St Johns County, FL; “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Harold Rake, St Johns County, FL; “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for John Rake.

15 “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for John Rake.

16 “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Flossie Rake and Alfred P Cyr; “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Adelaide Rake and Luther Stewart; “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for Flossie Cyr; “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 17, 2024), entry for Adelaide Stewart, St. Johns County, FL.

17 “Florida Marriages, 1830-1993,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org: accessed April 26, 2024), entry for Harold Rake and Eleanor Barrs, St. Johns County, FL.

18 “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for Harold Rake; “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Harold Everett Rake, Sharpes, Brevard County, FL.

19 “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Eleanor Rake, Putnam, Florida; “Harold Everett Rake,” FindAGrave.

20 “US Army WWI Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1918-1919,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed April 29, 2024), entry for George Rake, Army Serial Number 1356095.

21 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Harold Everett Rake, Sharpes, Brevard County, FL; “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Earl Otas Rake, Saint Augustine, St Johns County, FL.

22 “U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Earl Otis Rake; “US, WWII Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Wallace R Rake, Army Serial Number 34546114; “US, WWII Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Clark E Rake, Army Serial Number 34548524.

23 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Wallace Rudolph Rake, Crescent Beach, FL.

24 “US, WWII Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Harold E Rake, Army Serial Number 34799980.

25 George E. Cressman, Jr, “Camp Blanding in World War II: The Early Years,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 97, no. 1 (2018): 39-44, https://www.jstor.org/stable/45210098; Florida Department of Military Affairs, Camp Blanding, Florida: Three Unofficial Histories (St. Augustine, FL: Florida State Arsenal, 1988), digital collections, George A. Smathers Libraries, University of Florida, 7, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00047691/00001.

26 “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” Ancestry, John Rake.

27 Cressman, Jr, “Camp Blanding in World War II: The Early Years,” 54-55, https://www.jstor.org/stable/45210098.

28 “36th Infantry Division Roster,” Texas Military Forces Museum, Part 2, 86, accessed May 21, 2024, https://secureservercdn.net/50.62.194.59/385.ede.myftpupload.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/36thID-roster-part-2.pdf.

29 Shelby Stanton, Order of Battle U.S. Army, World War II (Novato: Presidio Press, 1984), 224.

30 “Rome – Arno 1944: The US Army Campaigns of World War II,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, accessed April 29, 2024, https://history.army.mil/brochures/romar/72-20.htm; “Anzio 1944: The US Army Campaigns of World War II,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, accessed April 29, 2024, https://history.army.mil/brochures/anzio/72-19.htm.

31 Cameron Zinsou, “Forgotten Fights: Operation Dragoon and the Decline of the Anglo-American Alliance,” The National WWII Museum New Orleans, August 17, 2020, accessed April 29, 2024, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/operation-dragoon-anglo-american-alliance; Bruce L. Brager, “The 36th Infantry Division: From the Alamo to Operation Anvil,” Warfare History Network, accessed April 29, 2024, https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/the-36th-infantry-division-from-the-alamo-to-operation-anvil/.

32 Stanton, Order of Battle U.S. Army, World War II, 224.

33 Stanton, Order of Battle U.S. Army, World War II, 224.

34 Zinsou, “Forgotten Fights: Operation Dragoon and the Decline of the Anglo-American Alliance,” https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/operation-dragoon-anglo-american-alliance; Brager, “The 36th Infantry Division: From the Alamo to Operation Anvil,” https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/the-36th-infantry-division-from-the-alamo-to-operation-anvil/.

35 Jeffrey J. Clark and Robert Ross Smith, Riviera to the Rhine (Washington: United States Army Center of Military History, 1993), 488; “36th Division’s Honor in History: The 100th Anniversary of WWI, 75th Anniversary of WWII,” Texas Military Department,accessed May 22, 2024, https://tmd.texas.gov/36th-division%E2%80%99s-honor-in-history-the-100th-anniversary-of-wwi-75th-anniversary-of-wwii.

36 “US, WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Harold E. Rake, Military Service Number 34799980.

37 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Harold E. Rake, St. Augustine, FL.

38 “36th Infantry Division,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, accessed April 29, 2024, https://history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/cbtchron/cc/036id.htm.

39 “The 36th Infantry Division During World War II,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed April 29, 2024, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-36th-infantry-division.

40 “Kaufering,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed April 29, 2024, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/kaufering.

41 “The 36th Infantry Division During World War II,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

42 “36th Infantry Division,” U.S. Army Center of Military History; “The 36th Infantry Division, The ‘Texas’ Division,” Texas Military Forces Museum, accessed May 22, 2024, https://www.texasmilitaryforcesmuseum.org/texas.htm; “36th Division’s Honor in History,” https://tmd.texas.gov/36th-division%E2%80%99s-honor-in-history-the-100th-anniversary-of-wwi-75th-anniversary-of-wwii.

43 “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” entry for Eleanor Rake.

44 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Eleanor B Scott, Putnam County, FL.

45 “Eleanor Barrs Rake,” FindAGrave, January 15, 2013, accessed April 21, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/103609019/eleanor_rake.

46 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for John Henry Rake, St Johns County, FL.

47 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Earl Otis Rake, St. Johns County, FL; “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Wallace R Rake, St. Johns County, FL.

48 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Flossie S Cyr, Dade County, FL.

49 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Adelaide Stewart, St Johns County, FL.

50 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Clark E Rake, Camp Hood, Coryell County, TX.

51 Don A. Schanche, “Hardluck ‘Triple Nickel’ Outfit Battles Way Back,” Tampa Bay Times, September 10, 1951, https://www.newspapers.com/image/332185062/?terms=rake&match=1.

52 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Clark Eugene Rake, St. Augustine, FL.

53 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for Harold E Rake; “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for John G Rake, St. Augustine, FL; “Annie J Reyes Rake,” FindAGrave, accessed April 21, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/3964987/annie_j_rake; “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for George Rake, St. Augustine, FL.

54 “US, WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Clark E Rake, Military Service Number 34548524.

55 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for Clark Eugene Rake.

© 2024, University of Central Florida