Ned Lamar Bostic (November 28, 1921 – October 14, 1943)

423rd Bombardment Squadron, 306th Bombardment Group, 8th Air Force

by Autumn Brinkmeier and Gramond McPherson

Early Life

Ned Lamar Bostic was born in Atlanta, GA on November 28, 1921 to Hubert and Regina Bostic.1 His parents, also natives of Georgia, married in their late teenage years around 1919 or 1920. In the 1920 Census, the couple lived in Jeff Davis County, GA in the south-central part of the state. Like many men in the region, Ned’s father and paternal grandfather worked as farmers.2 In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, cotton remained a primary crop grown in Georgia while in Jeff Davis County, tobacco served as the largest crop grown.3 Yet, by the time of Ned’s birth in 1921, his parents relocated around 200 miles northwest to Atlanta. Ned’s family likely followed the trend of rural Southern farmers who abandoned their farms to move to cities like Atlanta for greater employment opportunities in the 1920s and 1930s due to harsh farming conditions, decreasing prices for crops, and the impact of the boll weevil. In Atlanta in 1921, Bostic’s father worked in manufacturing as a metal worker.4

By the late 1920s, the Bostic family relocated south to Florida as the family grew with the birth of Ned’s sister Jacqueline Zona in 1927 in Riverview, FL near Tampa.5 During the 1920s, Florida experienced a land boom as the state’s population increased by over 300,000 between 1920 and 1925. For thousands of rural white and Black Georgians, the proximity of Florida for prospective employment appeared more tempting than going to the North and Midwest.6 By 1930, the family relocated to Central Florida, residing in Lake Mary, FL where Hubert worked as an ice puller or iceman. Icemen delivered ice to homes and businesses before the conveniences of an electric refrigerator.7 Bostic’s father shifted occupations during the 1930s as the family weathered the tough conditions of the Great Depression. By 1940, Hubert worked as a mechanic, where he earned an income of $750 in 1939, an income on the higher end compared to their neighbors.8

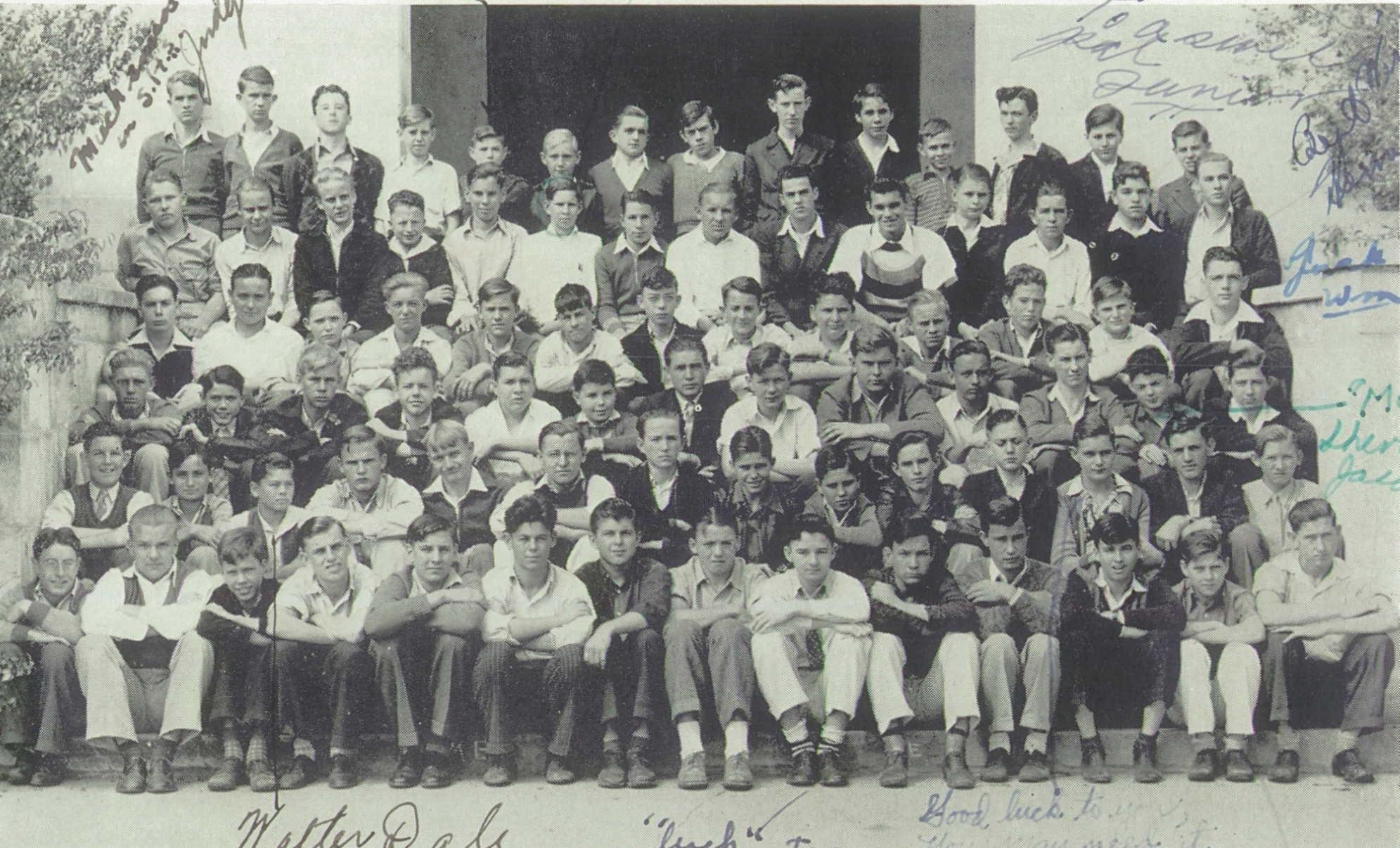

Various news reports in the Orlando Sentinel featured Ned’s involvement in his community as a member of a local Boy Scouts troop, a participant in a school play called “Lotus Flowers,” and his attendance along with his sister Jackie at a fish fry.9 As we see from this yearbook photograph, Bostic attended Seminole High School in Sanford, FL and appeared with the 1939 freshmen class.10 Ned did not complete his senior year of high school.11 By 1942, Ned’s family relocated north to Jacksonville, FL where Hubert worked as a mechanic for the Motor Transit Company which by 1936 had transitioned from streetcar operations to buses.12 The directory also lists Ned residing at his parent’s residence while working as a clerk.13

Military Service

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 brought the US into World War II and led to a significant expansion of the military draft. On February 14, 1942, Bostic (twenty years old) and his father (forty-one years old) registered at their local draft board in Jacksonville as part of the Third Selective Service draft registration that expanded the age range of draft-eligible men to include men from ages twenty to forty-four.14 Yet, like many young men eager to serve his country, Ned enlisted in the US Army Air Force at Camp Blanding, FL on July 8, 1942.15 In the summer of 1942, Ned likely completed basic training at Keesler Field in Biloxi, MS, one of the busiest Basic Training Centers for the Army Air Force. After four weeks of basic training, Bostic received further instruction at the Boeing Aircraft Plant in Seattle, WA for six additional weeks. At the Boeing plant, he gained a thorough education in the operation and maintenance of the B-17 heavy bomber, more commonly known as the Flying Fortress, produced there.16

Afterward, Bostic participated in the Army Air Force’s new flexible gunnery school in Las Vegas, NV in training for combat as an aerial gunner. The training program proved to be intense as aerial gunners adapted to ever-changing technology and lessons learned from the present conflict overseas. Ned trained to operate his gun turret blindfolded while wearing thick gloves to simulate the freezing temperature and lack of visibility that came with flying at up to 38,000 feet. Bostic and his fellow students learned to master each type of turret available at the time to be ready for whatever type of bomber or gun position they would be assigned to. Target practice remained a work in progress and as the war went on, students used various evolutions of simulations to practice their aim and reaction time. When firing, Ned and other gunners learned to account for the bullets drifting due to the movements and air resistance that came with flying. Training also included drills to identify friendly and enemy aircraft by silhouette and style, oxygen safety for high altitudes, and how to put on a gas mask if needed.17

On August 1, 1943, Ned, now a Staff Sergeant, joined the 423rd Bombardment Squadron, 306th Bombardment Group of the 8th Air Force who operated from Station 111 in Thurleigh, England, more than sixty miles north of London. During the war, the 306th would be known by its nickname, “The Reich Wreckers.”18 Ned initially flew with 2nd Lieutenant (2nd LT) Eugene Bumpus’s crew before transitioning to 2nd LT Robert McCallum’s crew on the Queen Jeannie, a B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber that held ten airmen.19 As the left waist gunner for his crew, Bostic defended the aircraft against the enemy, offered viewpoints for formations, assessed any damage incurred, and helped with any repairs if required.20 Throughout the war, the 423rd Bombardment Squadron, as part of the Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO), flew missions over Axis-occupied Europe with the Royal Air Force targeting key locations in the hopes of halting enemy production and limiting their military strength. In the squadron diary for the 423rd, the squadron targeted enemy manufacturing plants, airfields, factories, and submarines with some missions achieving success while other missions proved less effective, which required new strategies and tactics. Poor weather conditions, such as dense clouds made it difficult for aircrews to navigate and see targets and dangerous enemy aircraft. Additionally, the Allies faced off against the German Luftwaffe. It had a strong air defense system that attacked Allied aircraft with anti-aircraft artillery, known as flak (or flugabwehrkanone), which fired from the ground.21

Bostic flew in twelve or thirteen of these missions during his time with his unit.22 During these attacks, Ned and his fellow airmen experienced some relief from the dangers of missions. The squadron diary noted how night flying served as a way of training for landing and evading enemies in the darkness. On August 28 and 29, 1943, the diary notes how undesirable weather “gave the crews a peaceful weekend, night and day.”23 On October 14, 1943, the 8th Air Force’s 1st and 3rd Air Divisions flew from their bases in eastern England to raid Schweinfurt in the center of Nazi Germany. Mission No. 115 utilized 291 bombers, including Bostic and the crew of Queen Jeannie. The mission’s objective involved targeting a ball bearing factory previously attacked in August 1943 to further reduce the production of German weapons that required these ball bearings, thus giving the Allied forces a greater advantage. However, due to the distance between Thurleigh and Schweinfurt of approximately 400 miles, the Allied P-47 Thunderbolt fighter escort lacked the range to fly beyond the coastlines of France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. These flanking aircraft only offered protection to the bombers for about 200 miles before returning to base, leaving Bostic, his squadron, and the Allied aircrews relatively unprotected from German defenses over Nazi-occupied territory.24

As soon as the P-47 fighters reached their limits and departed, the Luftwaffe attacked, causing the B-17s to break their defensive formation. By the time the Americans approached Schweinfurt, their formations had already lost twenty-eight planes.25 One of these lost planes included Bostic and the crew of the Queen Jeannie. A survivor of the raid remarked "Those G— D— rockets. They'd hit a plane and it would disappear—17s blowing up all around—never saw so many fighters in my life, the sky was saturated with them.”26

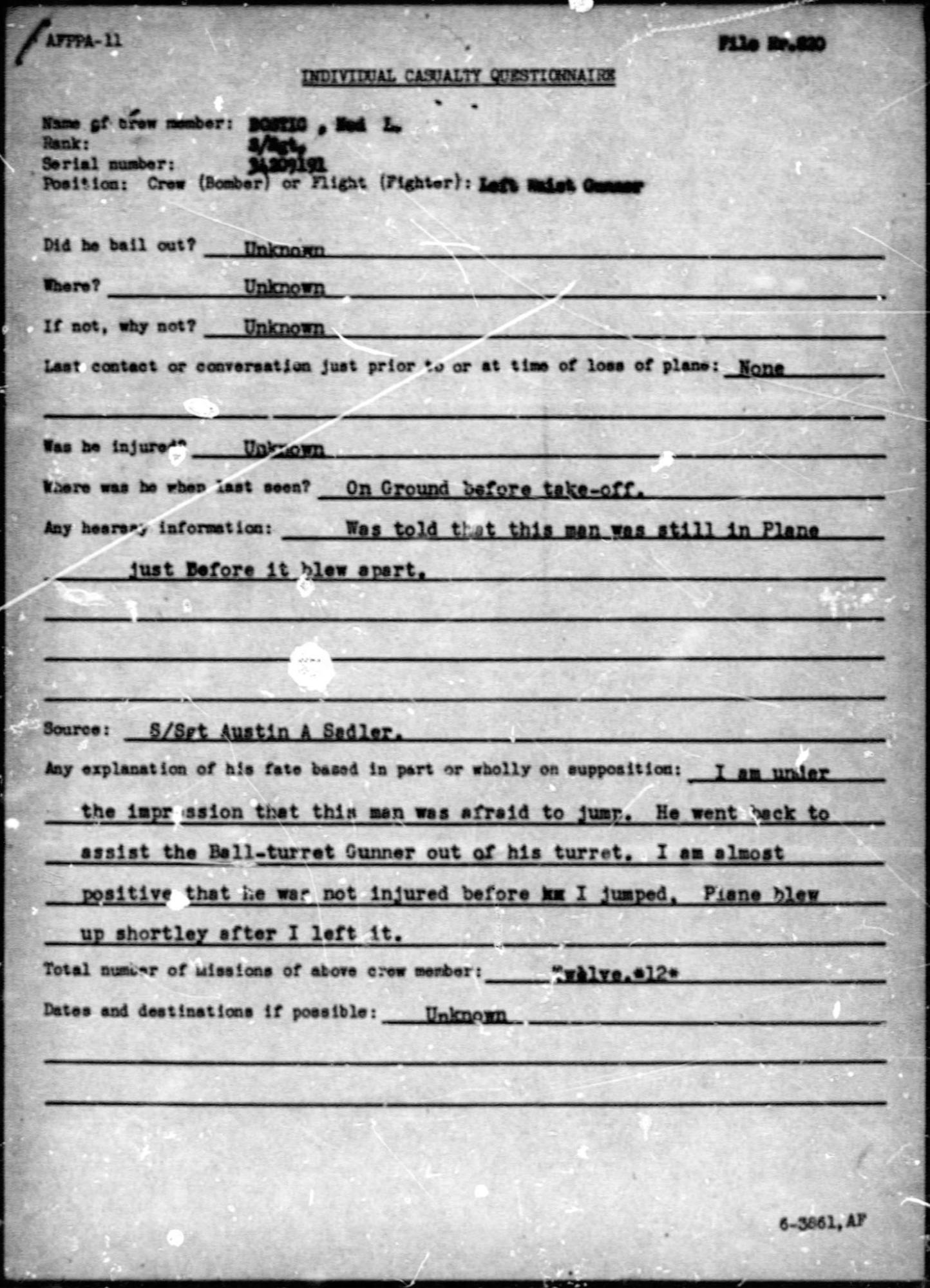

2nd LT McCallum tried to maintain control of the Queen Jeannie before giving the order to bail. Surviving crew members reported varying accounts of what happened next. Staff Sergeant Willard McQuerrie reported he believed Bostic went into mental shock or paralysis and could not jump. As seen on this missing air crew report, filled out by Staff Sergeant Austin Sadler, the last man to successfully bail out of the aircraft, after assisting ball turret gunner Staff Sergeant James Dunford, Bostic became afraid and did not want to jump. Sadly, Bostic and several other crewmen perished when the plane hit the ground near Dorne, Belgium. The wreckage found later showed that the plane had broken in two.27 While initially reported as missing, Ned and four others from the Queen Jeannie would be confirmed as killed in action. The other five men became prisoners of war before eventually being evacuated back to the US. Sixty Allied B-17s went down during this mission with over 600 aircrew casualties overall.28

Legacy

Though initially listed as missing in action in local newspapers in November 1943, by January 1944, the War Department confirmed his status as killed in action.29 Four days after his death on October 18, 1943, the Army Air Forces buried Ned and his fellow fallen soldiers in a cemetery at the Saint Trond Airfield in Belgium.30 In November 1949, the Miami Herald reported the return of Ned’s body to the US and on December 21, 1949, officials reinterred his body at the Saint Augustine National Cemetery in Florida. Today Ned rests in Section C, Site 131, alongside fellow Veterans and close to his home and family.31

Ned’s family continued to live in Jacksonville until at least 1950. Around 1943, the family grew with the birth of Ned’s sister Patricia. Due to Ned’s enlistment, training, and service overseas, he may have never met his younger sister. In 1947, Ned’s sister Jacqueline married Allen Behrens in Jacksonville and soon gave birth to a daughter named Judith. The family lived under one household in 1950 where Hubert continued to work as a mechanic, working on automobiles for a transfer company while his son-in-law Allen worked as a truck driver for the Interstate Trucking Company.32 Ned’s mother Regina died in 1955 in Jacksonville while his father Hubert lived until the age of eighty-one, passing away on July 9, 1982 in Jacksonville.33 Ned’s sister Jacqueline worked for AT&T as a phone operator for seventeen years. She eventually relocated to Georgia, where she passed away on December 6, 1999 at the age of seventy-two.34

While experiencing a tragic death, Ned Bostic did not die in vain. The B-17 crews of the Schweinfurt raid successfully dropped multiple direct hits on the factory. Although German production of the ball bearings only dropped ten percent as a result of the raids, the US Air Force learned major lessons about protecting bombers on deep missions, as the 8th Air Force changed their strategies to ensure safer missions until new technology allowed for improvements. The second Schweinfurt mission on October 14, 1943 became known as “Black Thursday,” recognizing the great sacrifice of Ned and hundreds of others.35 The Second Schweinfurt Memorial Association dedicated a plaque of the valiant effort of the airmen of the US 8th Air Force in the Memorial Park of the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Riverside, OH.36

Endnotes

1 Regina’s name is recorded as Redenia and Regan in different sources, but this biography uses Regina because that is how Ned spelled it on his draft card. “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Ned L Bostic, ED 0017, Lake Mary, Seminole, Florida; “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Ned Lamar Bostic.

2 The Bostic name is spelled Bostick in different sources, but this biography uses Bostic because that is how Ned spelled it on his draft card. “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Marcus C. Bostick, ED 0084, Hazlehurst, Jeff Davis, Georgia; “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Hubert E. Bostick, ED 115, Blackburn, Jeff Davis, Georgia; “1930 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry, Ned L Bostic.

3 Gregory A. Moore, Sacred Ground: The Military Cemetery at St. Augustine (St. Augustine, FL: Florida National Guard Foundation, 2013), 160; Elizabeth B. Cooksey, “Jeff Davis County,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, July 12, 2022, accessed June 23, 2023, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/counties-cities-neighborhoods/jeff-davis-county/.

4 “U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 22, 2023), entry for Hubert E Bostick, 1921, Atlanta, GA; “Jamil S. Zainaldin, “Great Depression,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, September 29, 2020, accessed June 25, 2023, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/great-depression/.

5 “U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 22, 2023), entry for Zona Jacqueline Bostic.

6 Gary R. Mormino, “Twentieth-Century Florida: A Bibliographic Essay,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 95, no. 3 (Winter 2017): 293, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44955689; “Florida’s Land Boom,” Florida Center for Instructional Technology, accessed June 26, 2023, https://fcit.usf.edu/florida/lessons/ld_boom/ld_boom1.htm.

7 Emma Grahn, “Keeping your (food) cool: From ice harvesting to electric refrigeration,” National Museum of American History, April 29, 2015, accessed June 22, 2023, https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/ice-harvesting-electric-refrigeration; “1930 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry, Ned L Bostic.

8 “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945”, database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Ned Bostick, 1935, Seminole, Florida; “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Ned L. Bostic, ED 59-19, Lake Mary, Seminole, Florida.

9 “Lake Mary Scouts From All Over World,” Orlando Sentinel, June 23, 1935, 8A; “Lake Mary News,” Orlando Sentinel, May 23, 1937, 7B; “Lake Mary News,” Orlando Sentinel, August 12, 1936, 5.

10 “U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-2016,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 22, 2023), entry for Ned Bostic, Seminole High School, Sanford, FL.

11 Bostic’s enlistment record states he completed 3 years of high school. “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946”, database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Ned L. Bostic.

12 “Ohio and Florida, U.S., City Directories, 1902-1960,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Hubert E. Bostic, 1941, Jacksonville, FL; Ennis Davis, “Lost Jacksonville: Streetcars,” The Jaxson Mag, December 26, 2018, accessed June 22, 2023, https://www.thejaxsonmag.com/article/lost-jacksonville-streetcars-page-2/.

13 On Bostic’s draft card on February 14, 1942, he states his employment status as unemployed. By the time of his enlistment on July 8, 1942, he worked in the bakery industry. It is unclear the month of publication for the city directory. “Ohio and Florida, U.S., City Directories, 1902-1960”, database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Ned L Bostic; “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records,” Ancestry, Ned L. Bostic; “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men,” Ancestry, Ned Lamar Bostic.

14 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947”, database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Hubert E. Bostic; “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men”, Ancestry, Ned Bostic; Ericka G., “World War II Selective Service Draft Registration,” Veterans Voices Research, May 13, 2020, accessed June 23, 2023, https://veteran-voices.com/world-war-ii-selective-service-draft-registrations/.

15 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records,” Ancestry, Ned L Bostic.

16 Moore, Sacred Ground, 160-162.

17 Moore, Sacred Ground, 162-163; Kelsey McMillan, “Aerial Gunner Training,” Bomber Legends 2, no. 2 (Summer 2005): 7-16, http://thebombercommand.info/DEDICATED_BOMBER_SQUADRON/DBS_TRAINING/AerialGunnery/BL_Mag_v2-2-GunneryTrain.pdf.

18 Fred C. Baldwin, Beekman H. Pool, and Joseph C. Brashares, 423rd Squadron Combat Diary: 1942-1945 306th Bomb Group, edited by Russell A. Strong (Charlotte: 306th Bomb Group Historical Association, 1993), 39, https://www.306bg.us/library/423combatdiary-text%20v2.pdf; Jonathan Moore, “306th Bomb Group,” American Air Museum in Britain, May 18, 2023, accessed June 15, 2023, https://www.americanairmuseum.com/archive/unit/306th-bomb-group.

19 “Boeing B-17E Flying Fortress,” The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, accessed June 15, 2023, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/visit/museum-campus/us-freedom-pavilion/warbirds/b-17e-flying-fortress; Lee Cunningham, “Ned L Bostic,” American Air Museum in Britain, February 15, 2015, accessed June 15, 2023, https://www.americanairmuseum.com/archive/person/ned-l-bostic; Moore, Sacred Ground, 158, 162.

20 “Waist Gunner,” Army Air Corps Library and Museum, accessed June 15, 2023, https://www.armyaircorpsmuseum.org/Waist_Gunner.cfm.

21 John M. Curatola, “‘Black Thursday,’ October 14, 1943: The Second Schweinfurt Bombing Raid.” National World War II Museum, New Orleans, October 17, 2022, accessed June 25, 2023, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/black-thursday-october-14-1943-second-schweinfurt-bombing-raid; Baldwin, Pool, and Brashares, 423rd Squadron Combat Diary, 24, 33, 46, 51, 60.

22 “Missing Air Crews Reports,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for aircraft 42-30813, Ned L. Bostic, 24, 27.

23 Baldwin, Pool, and Brashares, 423rd Squadron Combat Diary, 40.

24 William Fischer Jr., “Second Schweinfurt Memorial,” HMdb.org, August 26, 2022, accessed June 15, 2023, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=26279; Curatola, “‘Black Thursday,’” National World War II Museum.

25 Curatola “‘Black Thursday,’” National World War II Museum.

26 Baldwin, Pool, and Brashares, 423rd Squadron Combat Diary, 46.

27 Cunningham, “Ned L Bostic,” American Air Museum in Britain; “Missing Air Crews Reports,” Fold3, 11, 18, 24.

28 “Missing Air Crews Reports,” Fold3, 12; Curatola “‘Black Thursday,’” National World War II Museum.

29 “Official Army List of Missing,” Miami News, November 17, 1943, 5B; “Haines City Man Killed On Duty,” Tampa Times, November 17, 1943, 2; “Floridian is Killed in Action,” Miami Herald, January 14, 1944, 12B; “Four Floridans sic Are Casualties,” Tampa Times, January 14, 1944, 2.

30 In the reports, the name of the airbase is given as St. Trond. Saint-Trond is the name used by the French while the Belgians use Sint Truiden. Nathan Hood and Melissa Cox Norris, “The 25th General Hospital of WWII Experience: Airbase A-92 at Sint-Truiden,” University of Cincinnati Libraries, February 4, 2016, accessed June 23, 2023, https://libapps.libraries.uc.edu/liblog/2016/02/the-25th-general-hospital-of-wwii-experience-airbase-a-92-at-sint-truiden/; “Missing Air Crews Reports,” Fold3, 2.

31 “Florida War Dead Returned,” Miami Herald, November 12, 1949, 4A; “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Ned L Bostic.

32 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Hubert E. Bostie, ED 68-198, Jacksonville, Duval, Florida; “Florida, U.S., County Marriages, 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 23, 2023), entry for Zona Jacqueline Bostic.

33 “Florida, U.S., Death Index, 1877-1998,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Regina A. Bostic, Duval, Florida; “Florida, U.S., Death Index, 1877-1998,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Hubert E. Bostic, Duval, Florida.

34 Jacqueline’s obituary mentions two surviving sisters, Pat Wilson and Nancy McKinney of Jacksonville, FL. It is unclear the birth year of Nancy. “U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index,” Ancestry, Zona Jacqueline Bostic; “Jacqueline Behrens, AT&T Retiree,” Atlanta Constitution, December 7, 1999, J3.

35 Curatola “‘Black Thursday,’” National World War II Museum.

36 Fischer, “Second Schweinfurt Memorial,” HMDb.org.

© 2023, University of Central Florida