James Lynn Billington (January 12, 1923-June 24, 1944)

514th Fighter Squadron, 406th Fighter Group, 9th Air Force

By Brandy Watters and John Lancaster

Early Life

James Lynn Billington was born on January 12, 1923 in Calloway County, KY to Roy Ellis and Edna (née Palmer) Billington.1 At the time of James’s birth, the Billington’s had lived in Kentucky for at least three generations, as Roy’s parents and grandparents also called the state home.2 Roy, born September 30, 1900, grew up with his father, William; mother, Mary; brothers Eddie (1904) and William Jr. (1906); and sister Fannie (1916), on a farm his family owned.3 Edna, born September 19, 1900, also grew up in Kentucky.4 She and Roy married in Henry, TN, just south of the state border from Calloway County, on December 24, 1919.5 Shortly after their marriage, the couple settled in Marshall County, KY, where they both lived and worked on a farm they rented.6

Roy and Edna welcomed their first child, daughter Holly Hunter, in 1921.7 James Lynn, the couple’s first son, followed on January 12, 1923. James grew up as an older brother alongside seven siblings. He and Holly had five sisters, Priscilla (1925), Linda (1927), Brooks (1928), Jean (1930), and Frances (1931), and one brother, Charles (1942).8

By 1935, the Billington family had moved from Kentucky to Polk County, FL.9 This move south may have owed to the nationwide economic and agricultural struggles of the Depression years. Around this time, Roy accepted a position in the Agronomy Department at the University of Florida in Gainesville.10 Roy utilized his experience as a farmer in Kentucky to assist the department with improving sustainable food-production techniques at a time of agricultural crisis throughout the state, the nation, and the world.11 The Great Depression, which began after the stock market collapsed in October 1929, greatly affected the livelihoods of millions of Americans, and hit Florida’s agriculture sector especially hard. Though the state experienced a land boom in the early 1920s, two Hurricanes –the 1926 Great Miami Hurricane and the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane– together caused around $125 million in damages in the years before the Depression, which greatly hurt the state’s agricultural output.12 Additionally, in 1929, an infestation of Mediterranean fruit flies damaged the previously-growing citrus industry in the state, reducing production by up to sixty percent of pre-Depression levels.13 The start of the Great Depression that same year only made the situation in Florida worse. Roy’s position in the Agronomy Department at the University of Florida speaks to the need for skilled individuals to aid in statewide and national economic recovery efforts during this period.

James attended school throughout his early life, and graduated from Gainesville High School in 1940, a significant feat at a time when only about thirty percent of American teenagers graduated high school.14 Following his high school graduation, he attended the University of Florida for one year. In 1941, he left the University of Florida to enter the US Military Academy at West Point. He attended for one year before receiving a medical discharge.15

Military Service

James Lynn Billington enlisted in the US Army Air Force (AAF) at Orlando Army Air Base (later renamed McCoy Air Force base and today Orlando International Airport) on June 3, 1942.16 Originally opened in 1928 as the Orlando Municipal Airport, the US Army activated the location as the Orlando Army Air Base on September 1, 1940, as the war in Europe continued to intensify. By 1942, when James enlisted there, the Orlando Army Air Base expanded to encompass nearly one thousand acres, and included six runways.17

Following his enlistment, James reported to Maxwell Army Base, in Montgomery, AL, for pre-flight training to become a pilot. He then attended flight school in Florida with the 61st Flying Training Detachment, where he practiced flying single-engine aircraft.18 The 61st Flying Training Detachment trained at Lodwick Aviation Military Academy, a civilian-owned flight school based in Avon Park, FL, under contract to the US government as a basic and primary training airfield for new cadets. Between 1940 and 1944, over five thousand flight cadets trained at Lodwick Aviation Military Academy.19

By mid 1943, after completing pre-flight, basic, and primary training, James relocated to Moultrie, GA, where he continued his pilot training at Spence Air Base. During World War II, Spence Air Base served as an AAF Advanced Training Base for single engine planes. There, James flew at least eighty hours to hone his physical coordination, reflex, and piloting skills.20 While training in Moultrie, James met Josephine Palmer Haire, a Georgia native from a military family. Josephine’s father, Joseph Palmer Haire, served in both World War I, serving in France between October 1917 and April 1919, and World War II.21 Josephine and James married at the chapel at Spence Field on August 13, 1943. Less than a month later, in early September, 1943, 2nd Lieutenant James Billington earned his wings as a fighter pilot at Spence Field.22

After completing pilot training, the AAF assigned James to the 514th Fighter Squadron, 406th Fighter Group, 9th Air Force.23 Activated on March 4, 1943, the 514th Fighter Squadron remained stationed in the US for nearly one year. James likely joined his comrades of the 514th around the time it shipped out from Camp Shanks, NY on March 22, 1944. The unit arrived in Liverpool, England thirteen days later, on April 4, and shortly thereafter reported to their new station in Ashford, Kent, located about twenty miles west of Dover.24 While stationed in Ashford, the airmen of the 514th Fighter Squadron flew P-47 Thunderbolts –single-pilot planes capable of both high-altitude bombing and ground support–first introduced in April 1943.25

On May 9, 1944, the 514th commenced their first mission against enemy forces in Europe, a group sized fighter sweep near the commune of Berck-sur-Mer, a coastal town in northern France about forty-five miles south of Calais.26 A month later, on June 6, James and his fellow airmen participated in the D-Day landings at Normandy, France, providing both pre-invasion and invasion support for Allied ground forces.27

Shortly after the successful Allied invasion of German-occupied France at Normandy, the German Luftwaffe (air force) introduced new aerial weapons to the war effort. On June 13, 1944, they launched their first attack on London using V1 flying bombs. Powered by jet engines and unmanned, V1 flying bombs constituted an early example of a winged cruise missile. Due to the distinctive humming sound they made in the air, Allied airmen nicknamed these weapons doodlebugs.28 Between June 1944 and March 1945, the German military launched nearly seven thousand of these bombs at Britain, aiming the majority of them for London.29 German doodlebugs on their way to London often passed over the 514th Fighter Squadron’s station in Ashford, due to the base’s location about sixty miles south of the English capital. In mid June, 1944, Lt. James Billington became the first airman of the 514th to shoot down one of these German bombs.30

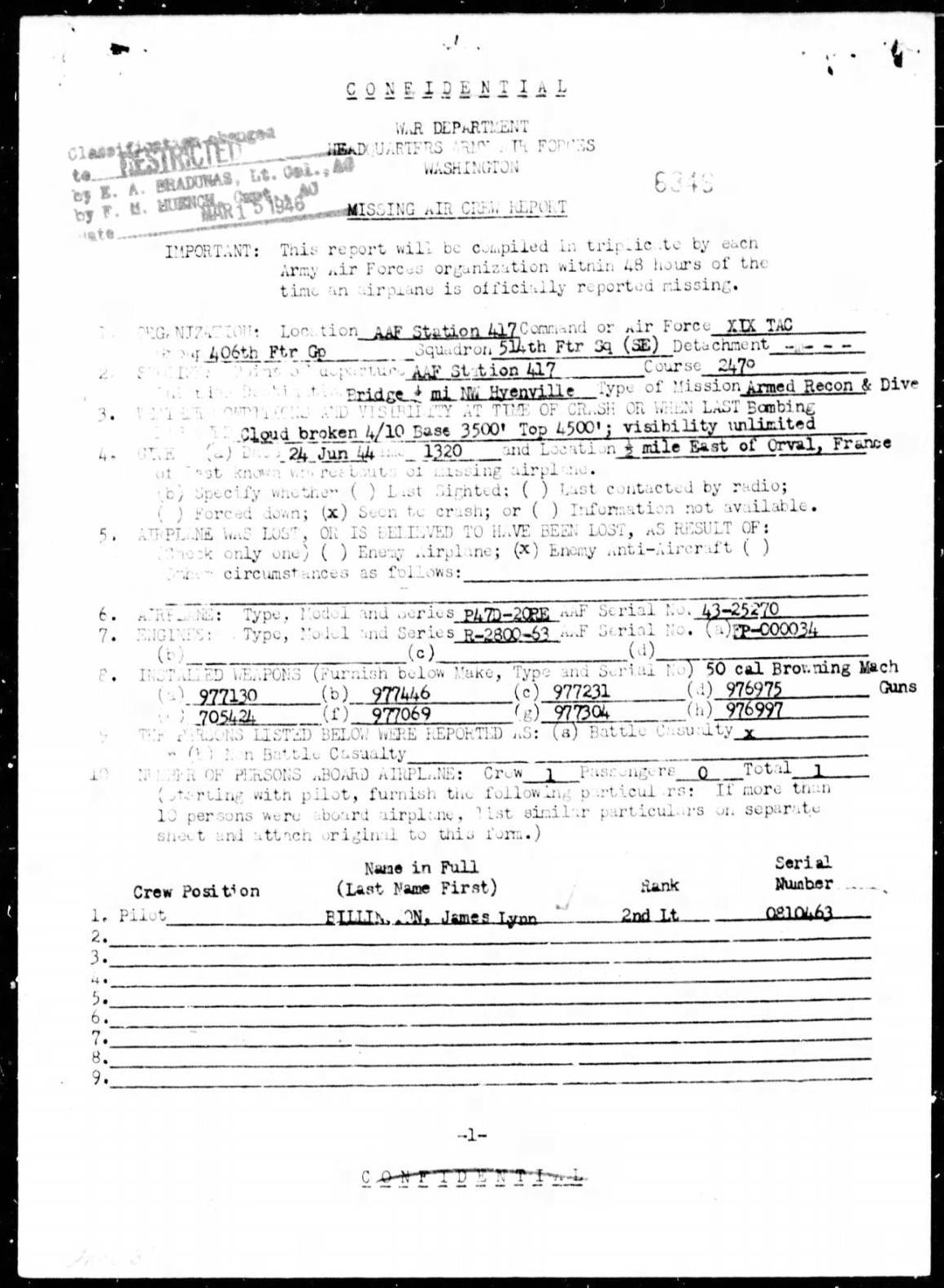

On June 24, 1944, James and a number of his comrades departed their base in Ashford on a reconnaissance and bombing mission near Hyenville, France, a coastal town about fifty miles south of Cherbourg, the Norman port city north of Omaha Beach. Flying their single-piloted Thunderbolt fighter planes, they arrived near their target around 1:30 p.m., seen on the Missing Air Crew Report here. James and his comrades successfully descended to make a pass on enemy personnel along a highway below, but encountered light anti aircraft fire upon ascent. The flak struck James’s plane at about five thousand feet. 2nd Lt. Weldon L. Tostenson, a fellow airman on this mission, witnessed James’s Thunderbolt quickly descend and spin down toward the ground. When he radioed James to bail out of his plane, he received no response. Traveling at an estimated four hundred miles per hour, 2nd Lt. James Lynn Billington crashed in a wooded area near the town of Orval, France. He was twenty-one years old.31

Legacy

James Billington's legacy is a story of heroism, sacrifice, and the profound impact individuals can have on the world, their country, and their loved ones. His story, and the stories of his fellow airmen, continue to inspire future generations to remember the cost of freedom and the valor of those who stand in its defense.

Although 2nd Lt. Tostenson observed James’s crash, US military personnel could not immediately recover his remains. As a result, the Army initially reported James as Missing in Action (MIA). Newspapers back home in the US continued to report on James’s status as MIA until early February 1945.32 This means that James’s family and loved ones did not know about his death for over seven months.

James’s comrades recovered his remains in early 1945 and initially interred them in a temporary Marigny-St.Lô military cemetery in Normandy, France.33 In the years after the war, military personnel relocated those buried in this temporary cemetery to their permanent resting places. Many now rest in the nearby Normandy American Cemetery and Brittany American Cemetery, both maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC).34 Before James could be moved, Roy Billington, as his son’s next of kin, decided, in 1948, to bring James back to Florida to rest closer to home.35 In December 1948, James and thirty-two other Veterans who fell in service traveled back to the US aboard the USAT Lt. James E. Robinson for permanent reburial.36 James Lynn Billington was buried on December 20, 1949 with his fellow servicemen and servicewomen in St. Augustine National Cemetery, section C, plot 198.37

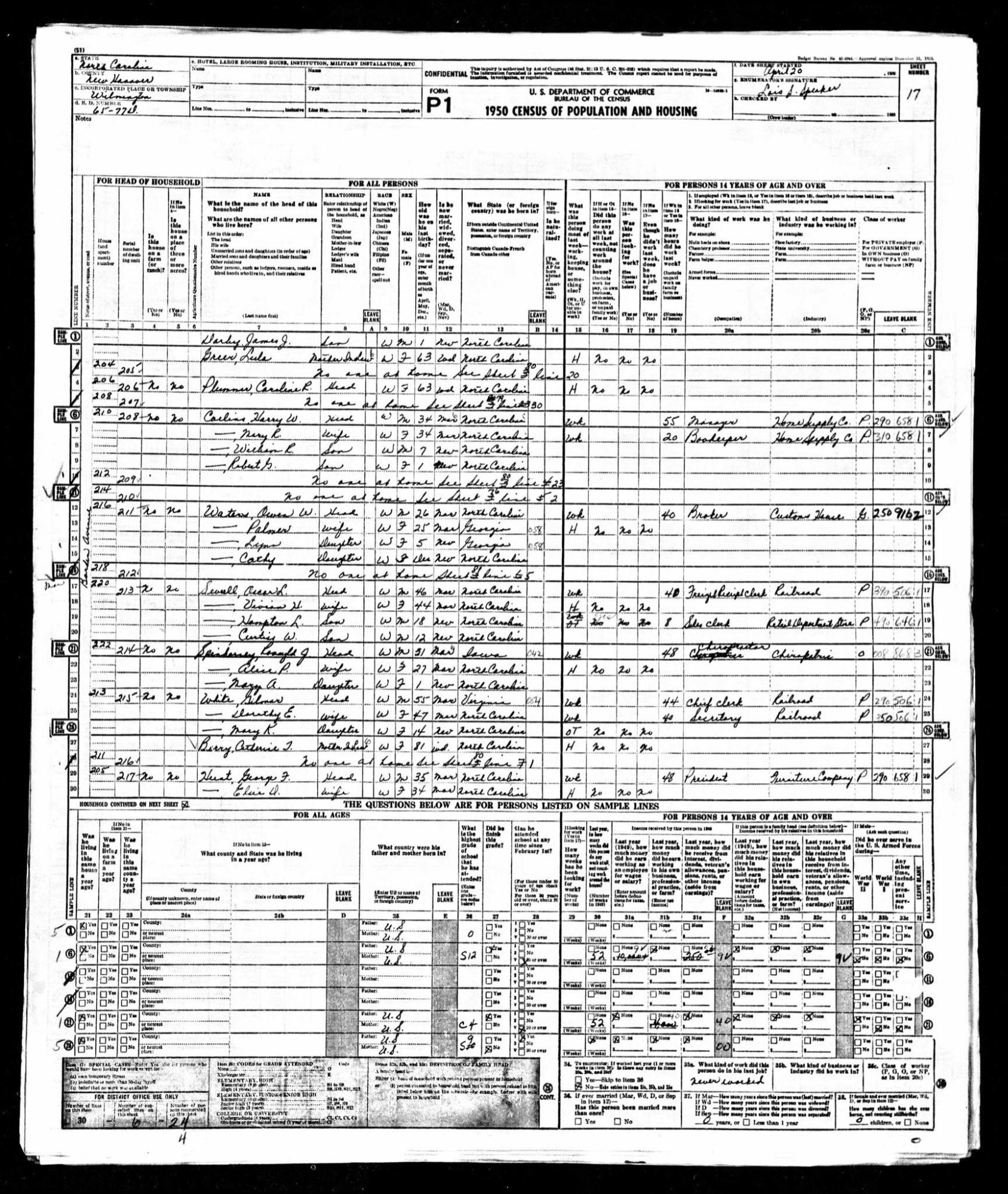

Josephine, James’s widow, continued to remember her husband after his death. On October 14, 1944, four months after James’s death, she welcomed their daughter, Pamela Lynn Billington.38 In remembrance of her husband, Josephine gave her daughter her father’s middle name.=Sometime before 1950, Josephine married Owen Waters, a customs house broker from North Carolina. In 1950, Josephine, Owen, Pamela Lynn, and Josephine and Owens’s one-year-old daughter, Cathy, lived in Wilmington, NC, seen on the US Federal Census here.39 Josephine died in 1978, aged fifty-three, and Pamela Lynn passed away in 2003, aged fifty-nine. Owen followed in 2013. They all now rest beside each other at Oakdale Cemetery, in Wilmington.40

The University of Florida, where James attended for one year, also commemorated James. Editors of the 1947 Seminole, the university’s yearbook, included an In Memoriam page for all those former students who had died during the war. James’s name appears on this page.41 In 1950, two of James’s sisters, Brooks and Jean, worked at the University of Florida, Brooks as a secretary and Jean as a library assistant. They both lived at home with their parents, Roy and Edna, and their younger brother, Charlie, in Alachua County, FL.42 Roy passed away on September 20, 1962, at the age of sixty-one. Edna passed away, aged ninety-three, on June 28, 1994. Today, they rest beside each other at Rosemary Hill Cemetery, in Levy County, FL.43

James’s legacy of military service also persists in a number of important ways. A monument memorializing the 406th Fighter Group, including James’s 514th Fighter Squadron, stands at the United States Air Force Academy in El Paso County, CO. Dedicated to the Veterans who served as part of the 512th, 513th, and 514th Fighter Squadrons of the 406th, the monument commemorates the 13,612 combat flights the airmen of these units collectively took in France, Belgium, England, and Germany throughout the course of the war.44 Additionally, a memorial plaque hangs in St. Mary’s church, in Great Chart, England, about two miles from the military base in Ashford where James and his comrades operated. The plaque, inscribed with the names of those airmen who died while stationed at Ashford Air Base during the war, also lists James.45

In the decades following World War II, the community of Dangy, France, located about thirteen miles east of the site of James’s crash in Orval, erected a monument dedicated to both James and Captain Jack Engman, another American airman who died near the same location. Engman, who served with the 366th Fighter Group, died on July 27, 1944, as American troops helped liberate Dangy from German control.46 The monument stands in a church cemetery in Dangy, and remains an important site of remembrance for the residents of the town. On July 27, 2014, for the seventieth anniversary of Dangy’s liberation, town officials placed wreaths beside the monument in commemoration of Lt. James Billington, Cpt. Jack Engman, and all those who died while liberating the city.47 Officials did the same for the seventy-fifth anniversary of the town’s liberation in 2019.48 At the 2014 commemoration, Domonique Pain, the mayor of Dangy, related the story of the town’s liberation and the deaths of both Billington and Engman for those present. Near the end of his remarks, he reflected, “seventy years after these events, we want to turn our thoughts to them Billington and Engman. We pay homage and express our profound gratitude to these two American aviators. Memory is a duty.”49

Endnotes

1 “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 16, 2024), entry for Roy Billington, Calloway County, KY; “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 16, 2024), entry for Roy Billington, Calloway County, KY; “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 16, 2024), entry for James L Billington.

2 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 16, 2024), entry for Roy Billington, Calloway County, KY.

3 “1910 United States Federal Census,” entry for Roy Billington; “1920 United States Federal Census,” entry for Roy Billington; “Roy Ellis Billington,” FindAGrave, March 7, 2013, accessed July 18, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/106328896/roy-ellis-billington?_gl=1*si6ohh*_gcl_au*ODIwNzMxMjYuMTcyMTE0MzExMw..*_ga*MjE4MDM4NjQzLjE3MjExNDMxMTQ.*_ga_4QT8FMEX30*NmI3ZWQzZmItMmNjMy00YjA3LThkZDYtMDc0MmU3N2M0MDM1LjIuMS4xNzIxNDEzMjk1LjQwLjAuMA..*_ga_LMK6K2LSJH*NmI3ZWQzZmItMmNjMy00YjA3LThkZDYtMDc0MmU3N2M0MDM1LjIuMS4xNzIxNDEzMjk1LjAuMC4w.

4 “Edna Pearl Palmer Billington,” FindAGrave, March 7, 2013, accessed July 18, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/106328897/edna_pearl_billington.

5 “Tennessee, U.S., Marriage Records, 1780-2002,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 16, 2024), entry for Miss Edna Pearl Palmer.

6 “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 16, 2024), entry for Edna Billington, Marshall County, KY.

7 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 16, 2024), entry for Hunter Billington, Calloway County, KY; “Roy E. Billington,” Tampa Tribune, September 21, 1962, 27.

8 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 16, 2024), entry for Roy Billington, Calloway County, KY; “Florida, U.S. State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 16, 2024), entry for Edna Billington, Polk County, FL; “Roy E. Billington,” Tampa Tribune, September 21, 1962; “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 16, 2024), entry for Charles E Billington, Alachua County, FL.

9 “Florida, U.S. State Census, 1867-1945,” entry for Edna Billington.

10 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 16, 2024), entry for Roy Ellis Billington.

11 “Vision and Mission,” University of Florida Agronomy, accessed July 18, 2024, https://agronomy.ifas.ufl.edu/.

12 “Hurricane of September 20th, 1926,” National Weather Service, accessed June 20, 2024, https://www.weather.gov/mob/1926Hurricane; “Memorial Web Page for the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane,” National Weather Service, accessed June 20, 2024, https://www.weather.gov/mfl/okeechobee.

13 “The Great Depression in Florida”, Florida Department of State, accessed June 17, 2024, https://dos.fl.gov/florida-facts/florida-history/a-brief-history/the-great-depression-in-florida/.

14 “Rites Sunday for Pilot at Gainesville,” Tampa Tribune, December 18, 1948, 2; David Leonhardt, “Students of the Great Recession,” New York Times Magazine (New York, NY), May 7, 2010, accessed July 19, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/09/magazine/09fob-wwln-t.html.

15 “Lt. J.L. Billington Missing in France,” Macon News (Macon, GA), July 11, 1944, 6; “Macon Flier is Missing,” Macon Telegraph (Macon, GA), July 11, 1944, 3; “Rites Sunday for Pilot at Gainesville,” Tampa Tribune, December 18, 1948.

16 “US, WWII Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed July 20, 2024), entry for James L Billington, Army Serial Number 14052677.

17 “Orlando Army Air Base,” Historical Marker Database, accessed July 20, 2024, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=54047.

18 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide: Preliminary Abridged Edition (St. Augustine, FL: St. Francis Barracks Special Archives, 1989), 187.

19 “Lodwick School of Aeronautics Cadet Publications,” Lakeland Public Library, accessed July 20, 2024, https://lakelandpubliclibrary.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15809coll53.

20 “Miss Haire, Lieutenant are Wed,” Moultrie News (Moultrie, GA), September 5, 1943, 14; “Spence Air Base During World War 2,” Spence Air Base, accessed July 20, 2024, https://spenceairbase.com/WW2.html.

21 “Georgia, U.S., World War I Service Cards, 1917-1919,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 20, 2024), entry for Joseph C. Haire; “U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1861-1985,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 20, 2024), entry for Joseph Cooper Haire; “Member of Rainbow Division Serves in Second World War,” Macon News (Macon, GA), September 6, 1944, 10.

22 “Miss Haire, Lieutenant are Wed,” Moultrie News (Moultrie, GA), September 5, 1943, 14; Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide, 187.

23 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for James L Billington.

24 “The History of the 514th in Brief,” 406th World War II Fighter Group, accessed July 20, 2024, https://www.406thfightergroup.org/514th-p1.php.

25 “P-47 D Thunderbolt,” National Museum of World War II Aviation, accessed July 20, 2024, https://www.worldwariiaviation.org/aircraft/republic-p47-thunderbolt; “The History of the 514th in Brief,” 406th World War II Fighter Group.

26 “The History of the 514th in Brief,” 406th World War II Fighter Group.

27 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide, 187; “The History of the 514th in Brief,” 406th World War II Fighter Group.

28 “The Terrifying German ‘Revenge Weapons’ of the Second World War,” Imperial War Museums, accessed July 20, 2024, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-terrifying-german-revenge-weapons-of-the-second-world-war.

29 “British Response to V1 and V2,” The National Archives, accessed July 20, 2024, https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/british-response-v1-and-v2/.

30 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide, 187; “The History of the 514th in Brief,” 406th World War II Fighter Group.

31 “US, Missing Air Crew Reports (MACRS), WWII, 1942-1947,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed July 20, 2024), entry for James Lynn Billington, Serial Number 0810463.

32 “Member of Rainbow Division Serves in Second World War,” Macon News (Macon, GA), September 6, 1944, 10; “85 Georgians are Killed in Action, Two are Missing, Two Wounded,” Atlanta Constitution, February 4, 1945, 5B.

33 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for James L Billington.

34 “Normandy American Cemetery,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed July 21, 2024, https://www.abmc.gov/normandy; “Brittany American Cemetery,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed July 21, 2024, https://www.abmc.gov/Brittany.

35 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for James L Billington.

36 “33 War Dead Coming Home,” Tampa Tribune, December 10, 1948, 9.

37 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for James L Billington.

38 “Pamela Lynn Billington Waters,” FindAGrave, April 5, 2011, accessed July 22, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/67926801/pamela_lynn_billington_waters.

39 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 22, 2024), entry for Palmer Waters, New Hanover County, NC.

40 “Pamela Lynn Billington Waters,” FindAGrave, April 5, 2011; “Owen William ‘Bill’ Waters Jr.,” FindAGrave, March 10, 2013, accessed July 22, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/106445703/owen_william_waters; “Palmer Haire Waters,” FindAGrave, April 5, 2011, accessed July 22, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/67926874/palmer_waters.

41 “U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-2016,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 22, 2024), entry for James L Billington.

42 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 22, 2024), entry for Roy E Billington, Alachua County, FL.

43 “Roy Ellis Billington,” FindAGrave, March 7, 2013; “Edna Pearl Palmer Billington,” FindAGrave, March 7, 2013.

44 “406th Fighter Group, 512th Squadron, 513th Squadron, 514th Squadron, 9th Air Force,” Historical Marker Database, accessed July 22, 2024, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=163533.

45 “RAF Ashford Roll of Honor,” War Memorials Online, accessed July 22, 2024, https://www.warmemorialsonline.org.uk/memorial/213328.

46 “Cpt Jack Engman and Lt James Billington,” American War Memorials Overseas, accessed July 22, 2024, https://www.uswarmemorials.org/html/monument_details.php?SiteID=660&MemID=944.

47 “Cérémonie de la Libération et hommage aux aviateurs,” Ouest France, July 30, 2014, accessed July 22, 2024, https://www.ouest-france.fr/normandie/dangy-50750/ceremonie-de-la-liberation-et-hommage-aux-aviateurs-2734133.

48 “Dangy. 75e D-Day: la commune honore ses disparu,” Ouest France, July 30, 2019, accessed July 22, 2024, https://www.ouest-france.fr/normandie/dangy-50750/dangy-75e-d-day-la-commune-honore-ses-disparus-6463559.

49 “Cérémonie de la Libération et hommage aux aviateurs,” Ouest France, July 30, 2014, translation by John Lancaster, accessed July 22, 2024, https://www.ouest-france.fr/normandie/dangy-50750/ceremonie-de-la-liberation-et-hommage-aux-aviateurs-2734133.

© 2024, University of Central Florida