Harvey Charles Singleton (October 8, 1914–April 22, 1944)

Headquarters Battery, 41st Field Artillery Battalion, 3rd Infantry Division

By Angela Hubbart and Luci Meier

Early Life

Harvey Charles Singleton was born in Vero Beach, FL on October 8, 1914, to Charles Singleton and Maude Singleton (née Bobo).1 Harvey’s father Charles was born and raised in Florida while his mother Maude was born in Mississippi before her family moved to Florida sometime during her childhood.2 Maude had previously wed Edward King before marrying Charles in 1913, starting a family soon thereafter with Harvey’s birth in 1914.3 In addition to his parents, Harvey shared a home with two younger siblings: a brother, Bruce William (1916), and a sister, Sarah Elizabeth (1921).4

Growing up, Harvey’s mother stayed home to raise the children and maintain the household while his father worked various jobs as a laborer across different industries including in wood yards, an orange grove, and in the dairy industry. Due to Charles’s shifting work history, the Singleton family moved around several different rental homes throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Despite the economic uncertainty they faced during the Great Depression, the family remained in the Brevard County area.5 The creation of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) as part of the New Deal provided jobs to a large percentage of struggling Americans including the Singleton family.6 In 1940, Charles worked in a rock pit, employed by the WPA.7

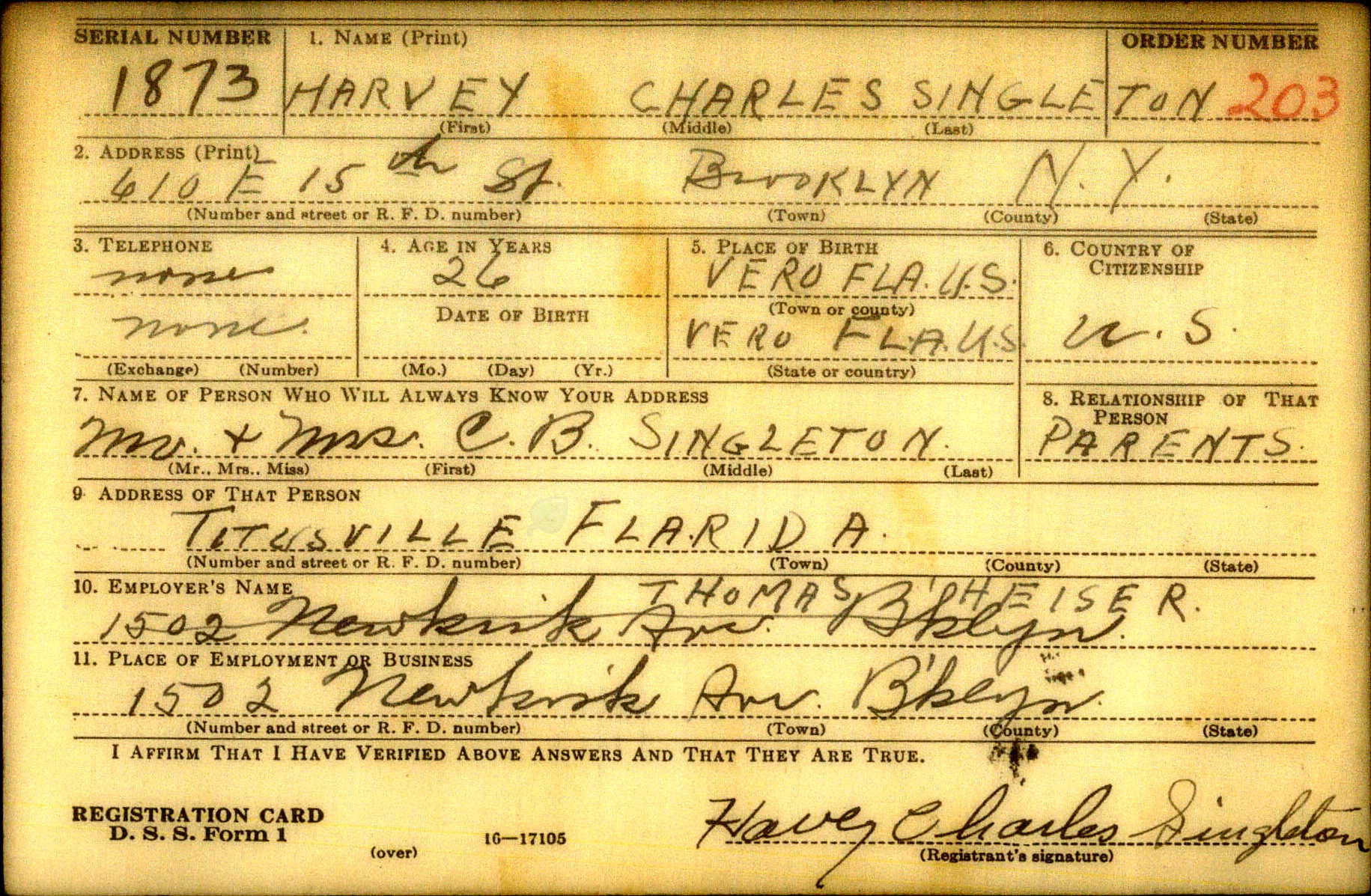

Through difficult times, Harvey’s parents prioritized their children's education. Charles achieved no more than a middle school education and Maude completed only part of high school yet all of the Singleton children graduated high school. Harvey completed some schooling at the college level. By 1940, both Harvey and his brother Bruce had moved out of the family home. Bruce lived with his new wife and son in his in-laws’ home and Harvey lived in New York where he worked as a chauffeur for a taxi company.8 On October 16, 1940, Harvey registered for the military draft in Brooklyn, NY.9 He continued to work as a chauffeur until his enlistment into the US Army.10

Military Service

Harvey Singleton enlisted on February 28, 1941, in Jamaica, NY.11 He eventually achieved the rank of Technical Sergeant in the 41st Field Artillery Battalion, 3rd Infantry Division (ID).12 Field artillery units include the large guns–field artillery pieces–and the personnel needed to fire, supply, and maintain this weaponry. During World War II, the War Department triangularized all infantry divisions; every division comprised three artillery battalions each assigned to one of the division’s three infantry regiments. This method of pairing the artillery with the infantry allowed for greater cooperation and, ultimately, efficacy of the artillery in supporting the infantry troops.13

The 3rd ID, also known as the “Fighting Third,” earned the nickname the “Rock of the Marne” for its resiliency in its fight against the Germans along the Marne River in France during World War I.14 The 3rd ID maintained this level of strength and commitment throughout World War II. In preparation for its involvement overseas, the 3rd ID primarily trained for amphibious landings. Its first of these landings occurred on November 8, 1942, during the invasion of French Morocco in North Africa known as Operation Torch. The Allies hoped to capture some of the large port cities including Casablanca, the 3rd ID’s target. The successful capture of Casablanca provided a port for the Allies to move troops and supplies into the continent to eventually defeat the Axis powers in North Africa.15

Then, in 1943, the 3rd ID moved to join the invasion of Sicily. On July 10, 1943, the division launched its second amphibious assault, this time on the shores of Licata, located on the south coast of Sicily. Opposed by German and Italian forces, the 3rd ID secured Licata and marched toward Palermo, the capital of Sicily. It took just over a month for the Allies to clear Sicily of enemy forces. The fight then shifted to mainland Italy. In mid-September, after Italy’s surrender, the 3rd ID joined forces with the Allied troops that had landed at Salerno. As the German troops retreated farther into Italy, they engaged the Allied forces, however, they proved unsuccessful as the American and British troops continued to advance. On October 13, 1943, Harvey and the other 3rd ID artillerymen positioned themselves-concealed behind a hill-in preparation for the crossing of the Volturno River. The artillery bombarded the Germans, firing 12,000 rounds of ammunition in just twenty-four hours. After successfully crossing the Volturno, the 3rd ID fought German opposition toward Cassino, a town less than 100 miles southeast of Rome.16

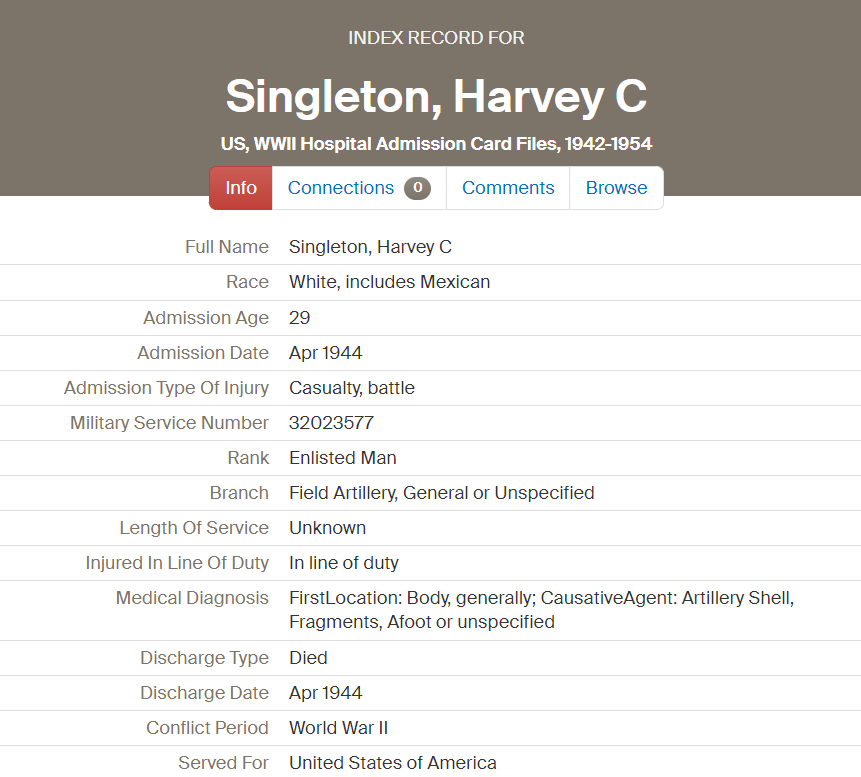

With the fighting in Cassino at a stalemate, Harvey and the rest of the 3rd ID aided in another amphibious landing referred to as Operation Shingle. Allied leaders hoped that staging an assault along the coasts of Anzio and Nettuno-located about thirty miles south of Rome-would force Germany to withdraw troops from Cassino and the Gustav Line, the German defensive preventing the Allies from securing Cassino and heading to Rome. Operation Shingle launched on January 22, 1944. Despite having previously abandoned Anzio, German forces returned with stiff resistance. The Germans waged counterattacks, firing upon the Anzio beachhead for weeks.17 Three months after his initial landing on the Anzio beachhead, fragments from an artillery shell killed Harvey Singleton. He died on April 22, 1944, at just twenty-nine years old.18

Legacy

After Harvey’s death, the 3rd ID continued the fight at Anzio, eventually achieving a breakthrough in May. His unit officially entered Rome on June 4, 1944.19 A memorial for the 3rd ID and its involvement at the Anzio beachhead is located near Nettuno. It reads:

January 22, 1944 U.S. Third Infantry Division made an assault amphibious landing here in this vicinity established a beachhead which was maintained for four months at great sacrifice of human life, and with indomitable courage in a valiant and sanguinary attack the division led an offensive that destroyed the strong German defenses and culminated in the liberation of Rome.20

Ultimately, the 3rd ID suffered more casualties than any other division as the only American division that fought the Nazis on every front of the war.21

Although Harvey never married or had any children, he did leave behind his parents and his siblings. In 1945, his sister Sarah still lived in Titusville with her four-year old daughter Sheila and their parents while her husband served in the US Army.22 By 1950, Sarah and her family had moved to New York where she and her husband both worked at a VA hospital.23 Sarah eventually returned to Florida where she died in 2008 at the age of eighty-seven.24 Harvey’s brother Bruce moved his family to Ohio prior to 1950. In addition to their firstborn, Samuel, they added a second son, Bruce Jr., to their family. Bruce and his wife, Annie, moved back to Florida in 1979 where he passed away fifteen years later.25 The Singleton parents, Charles and Maude, remained in Florida.26 Charles eventually retired as a drawbridge tender before passing from an illness in 1965.27 Maude died in 1960 at seventy-three years old.28

Harvey Singleton was first interred, not long after his death, in Nettuno Cemetery, Italy, in 1944.29 Due to his parents’ wishes, his body was returned to the United States aboard a US Army transport called the “Carroll Victory” and brought to Florida.30 He was reinterred in St. Augustine National Cemetery on August 11, 1948, in Section C, Site 199, his final resting place.31 Harvey’s name was one of many listed on the Memorial to the Fallen that was dedicated on November 11, 2013–Veterans Day. It stands near the Veterans Hospital in Lake Nona, to honor fallen soldiers from Central Florida.32

Endnotes

1 “TSGT Harvey Charles Singleton,” Find A Grave, accessed April 22, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/9439167/harvey_charles_singleton.

2 “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Harvey Singleton, La Grange, Brevard, Florida; “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Maud E Bobo, Woodley, Brevard, Florida.

3 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Maude King, Saint Lucie, Florida; “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Charles B Singleton and Maude E King.

4 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Harvey C Singleton, La Grange, Brevard, Florida.

5 “1920 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry, Harvey Singleton; “1930 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry, Harvey C Singleton; “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Harvey Singleton, Brevard, Florida.

6 “Works Progress Administration (WPA),” History, accessed May 13, 2024, https://www.history.com/topics/great-depression/works-progress-administration.

7 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Charlie B Singleton, Brevard, Florida.

8 “1940 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry, Charlie B Singleton; “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Bruce Singleton, Brevard, Florida; “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Harvey Singleton, Kings, New York.

9 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Harvey Charles Singleton, Brooklyn, New York.

10 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Harvey C Singleton, Service Number 32023577.

11 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” Ancestry, Harvey C Singleton.

12 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Harvey C Singleton, St. Augustine, Florida.

13 William G. Dennis, “U.S. and German Field Artillery in World War II: A Comparison,” The Army Historical Foundation, accessed May 14, 2024, https://armyhistory.org/u-s-and-german-field-artillery-in-world-war-ii-a-comparison/.

14 Sydney Johnson, “What to Know About the 3rd Infantry Division of the U.S. Army,” United Service Organizations, November 17, 2021, accessed May 14, 2024, https://www.uso.org/stories/2918-what-to-know-about-the-3rd-infantry-division-of-the-u-s-army.

15 Donald G. Taggart, ed., History of the Third Infantry Division in World War II (Washington: Infantry Journal Press, 1947), 3-34, https://ia801200.us.archive.org/28/items/HistoryOfTheThirdID-nsia/HistoryOfTheThirdID.pdf.

16 Taggart, History of the Third Infantry Division in World War II, 51-102.

17 “Anzio-The Invasion That Almost Failed,” Imperial War Museums, accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/anzio-the-invasion-that-almost-failed; United States Army, Anzio Beachhead, 22 January-25 May 1944 (Washington: Center of Military History, 1990), https://history.army.mil/html/books/100/100-10/CMH_Pub_100-10.pdf.

18 “US, WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Harvey C Singleton, Military Service Number 32023577; “Killed in Action,” Press Journal (Vero Beach, FL), June 9, 1944, https://www.newspapers.com/image/887158181/?terms=singleton&match=1.

19 “Legacy of Liberation: Operation Shingle and the Anzio Landings,” Commonwealth War Graves Commission, accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.cwgc.org/our-work/blog/legacy-of-liberation-operation-shingle-the-anzio-landings/.

20 “3rd Infantry Division Marker-Operation Shingle,” American War Memorials Overseas, accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.uswarmemorials.org/html/monument_details.php?SiteID=1369&MemID=1791&keyword=3rd%20infantry%20division.

21 “3rd Infantry Division,” Sons of Liberty Museum, accessed May 16, 2024, https://www.sonsoflibertymuseum.org/3rd-infantry-division-ww2.cfm.

22 “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Edgar Singleton, Brevard, Florida.

23 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Sarah S Mangiarella, Canandaigua, Ontario, New York.

24 “Sarah Elizabeth Singleton Mahan,” Find A Grave, accessed April 22, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/88996490/sara_elizabeth_mahan.

25 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Bruce W Singleton, Amherst, Lorain, Ohio; “Obituaries–Bruce Singleton,” Florida Today, March 30, 1994, https://www.newspapers.com/image/178450656/?terms=singleton&match=1.

26 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 22, 2024), entry for Charles B Singleton, Brevard, Florida.

27 “Obituaries–Mr. Charles B. Singleton,” Orlando Sentinel, April 18, 1965, https://www.newspapers.com/image/223845370/?terms=singleton&match=1.

28 “Maude Ellen Bobo Singleton,” Find A Grave, accessed April 22, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/88995703/maude_ellen_singleton.

29 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” Ancestry, Harvey C Singleton.

30 “Six War Dead Return Home,” Orlando Evening Star, July 7, 1948, https://www.newspapers.com/image/340908542/?terms=singleton&match=1.

31 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide: Preliminary Abridged Edition (St. Augustine, FL: St. Francis Barracks Special Archives, 1989), 186, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00047708/00001/images/186.

32 “Help Us Honor The Fallen Of Central Florida,” Orlando Sentinel, June 30, 2013, https://www.newspapers.com/image/269063729/?terms=singleton&match=1.

© 2024, University of Central Florida