Meredith MacDonald Mills, Jr. (April 21, 1923-July 21, 1944)

365th Bombardment Squadron, 305th Bombardment Group, 8th Air Force

by Jessica Ayuso and John Lancaster

Early Life

Meredith MacDonald Mills, Jr. was born on April 21, 1923 in Deland, Florida, the only child of Meredith M. and Russie (née Ware) Mills.1 During World War I, Meredith Mills, Sr. served in France in the 61st Artillery Regiment, Battery F of the US Army Coast Artillery Corps (CAC), as a Private First Class. Mills, Sr. and the 61st left for France in July, 1918, and remained there until February, 1919. They were still completing training exercises when the Armistice was signed in November, 1918.2 Russie Ware worked as a schoolteacher in Bradford County, FL prior to her son’s birth in 1923.3 Both of Mills’s parents hailed from Georgia but had relocated to Florida by the early 1920s.4 On June 5, 1923, less than two months after Mills’s birth, Meredith Mills, Sr. traveled from Deland to Eustis, FL to sit for the State Board of Pharmacy’s pharmacist exam. The day after he took the exam, the Tampa Morning Tribune noted that the 1923 participants constituted the largest exam group to date.5 Mills, Sr. subsequently received his certification as a pharmacist in the state of Florida, and began his career in a drugstore in Deland.6 The Mills family relocated from Deland to St. Augustine sometime after 1935, where Mills, Sr. continued his work as a pharmacist.7

Florida experienced a land boom in the 1920s. Increasing financial prospects of the growing middle class, fueled by credit that was easy to obtain, attracted land developers as well as both tourists and families that settled in the state.8 Agricultural, industrial, and economic growth contributed to a population increase of nearly half a million people between 1920 and 1930.9 The Mills family’s relocation from Georgia to Florida prior to Meredith Mills, Jr.’s birth in 1923 suggests a connection to these trends. Beginning mid decade, though, Florida’s real estate bubble began to burst, and the state struggled throughout the later 1920s for a variety of reasons. Banking and credit crises, along with relentless hurricane seasons in both 1926 and 1928, negatively impacted the state’s economy. An invasive fruit fly infestation in 1929 wounded the previously fast-growing citrus industry.10 The Great Depression, which followed the stock market crash in October 1929, destabilized the global, national, and state economies in the 1930s. Hard economic times impacted countless families across the US, as national average household income dropped forty percent by 1933.11

These circumstances affected the Mills family; in 1930 they owned their home in Deland, but by 1935 they must have sold it, as they rented a home outside the city limits.12 In 1940, after moving to St. Augustine, they rented a home at 29 Riberia St., just a few blocks from St. Augustine’s historic center.13 Still, Mills Sr.’s occupation as a pharmacist likely afforded the family a greater level of economic stability throughout the depression years. For instance, while statistics show that in 1930 only thirty percent of American teenagers graduated from high school, as many instead joined the workforce to help pay family bills, Meredith Mills, Jr. completed high school.14 Even more rare, as we see from his 1942 yearbook picture, Mills attended college at the University of Florida (UF) in Gainesville, though he never graduated.15 He enjoyed an active social life at UF, where he was a member of Phi Kappa Tau fraternity, and earned the nickname ‘Sparky.’16

Military Service

In June 1942, just weeks after US troops won the Battle of Midway against Japanese forces, Mills came home from UF and registered for the draft in St. Augustine.17 Meredith Mills, Jr. joined the US Army Air Corps on October 30, 1942. After his initial training at Camp Blanding, FL, he deployed to support the Allied Powers fight against Nazi forces in Europe.18 He rose to the rank of Staff Sergeant (SSgt) and served in the 365th Bombardment Squadron, 305th Bombardment Group of the 8th Air Force.19

In December 1942, the 305th relocated to Chelveston, England for the duration of the war.20 This location gave the Allied air forces prime access to the European Theater. The squadrons of the 305th flew B-17 Flying Fortresses.21 Boeing produced over 12,000 of these bombers during World War II. The US utilized them to fly extensive bombing raids over both the European and Pacific Theaters. B-17s could sustain heavy damage and, along with a heavy bomb payload, boasted up to thirteen machine guns.22 With a maximum crew of ten, typically four enlisted crew members served as dedicated machine gunners, while two of the officers manned guns when under attack.23 At five foot, six inches and 150 pounds, SSgt. Mills served as a ball turret gunner.24 This position often went to smaller airmen, as it required them to fold into the fetal position in a plexiglass sphere on the underside of the plane. The ball turret could rotate 360 degrees via an electro-hydraulic system, which allowed the gunner to protect the B-17 against attacks from below.25

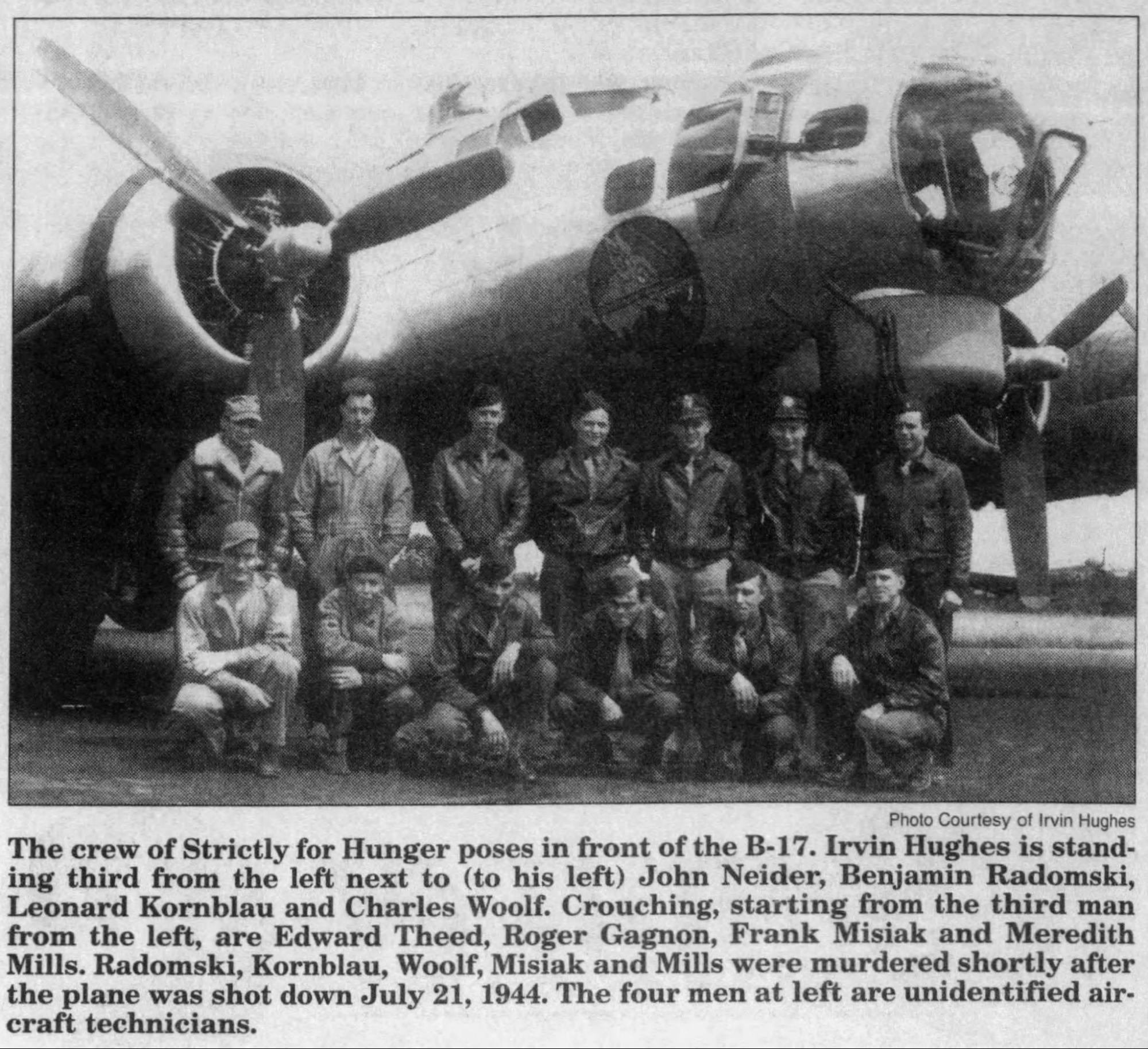

On July 21, 1944, a B-17 named Strictly for Hunger, manned by a nine-member crew, set off through the skies with almost 1,000 other heavy bombers to destroy a number of German industrial sites.26 As we see in a photograph of the Strictly for Hunger’s crew, SSgt. Mills flew this mission alongside 1st Lt. Leonard A. Kornblau, Pilot, of Wilkes-Barre, PA; 2nd Lt. William E. Boyd, Bombardier, of Auxvasse, MO; 2nd Lt. Bernard E. Radomski, Co-Pilot, of Buffalo, NY; 2nd Lt. Charles E. Woolf, Navigator, of Lawrence, KS; SSgt. Irvin E. Hughes, Waist Gunner, of Palmyra, PA; SSgt. Frank L. Misiak, Tail Gunner, of Cicero, IL; TSgt. Edward A. Theed, Top Turret Gunner, of South Jacksonville, FL; and TSgt. Roger G. H. Gagnon, Radio Operator, of Quebec, Canada.27 Shortly after the Strictly for Hunger successfully dropped bombs near Munich, Germany, an anti-aircraft shell struck it. Although the Flying Fortress went down in flames, SSgt. Mills and his other eight crewmates successfully bailed out via parachutes. They landed in southwest Germany, north of the Swiss border.28

The Army Air Corps initially reported Mills and the other eight members of the Strictly for Hunger as MIA. By July 23, two days after the crash, they had determined that four of the crew were taken prisoner by German soldiers and sent to POW camps, while the other five, including Mills, remained MIA but presumed dead.29 The families of Mills, Kornblau, Radomski, Woolf, and Misiak did not know for certain what happened to their loved ones until after the war. By summer 1945, officials from the French Army’s War Criminals Investigation Branch determined that German civilians had captured and murdered the five missing servicemen.30 Following the war, a Buffalo, NY-area newspaper reported that after the crew bailed out of their plane on July 21, 1944, several airmen landed and were captured by local civilians in Schollach, a town in Southwest Germany about eighty miles southeast of Strasbourg, France.31 The civilians brought the airmen to the town hall, where Benedikt Kuner, the town’s Nazi municipal district leader, or kreisleiter, ordered the American airmen shot to death.32 At least two other crew members from the Strictly for Hunger, including Mills, landed near the town of Urach, Germany, about eight miles north of Schollach.33 Local guards captured the airmen who landed near Urach and initially intended to march them to Schollach and turn them over to the German Army there. The situation took a violent turn when at least three armed civilians, led by Kuner, shot and killed the airmen along the way, including Meredith Mills, Jr.34 In all, Germans killed 1st Lt. Kornblau, 2nd Lt. Radomski, 2nd Lt. Woolf, SSgt. Misiak, and SSgt. Mills. The rest of the crew, 2nd Lt. Boyd, SSgt. Hughes, TSgt. Theed, and TSgt. Gagnon survived the remainder of the war in German POW camps.35 This shocking story of murder, while not wholly uncommon during the war, nevertheless made international headlines, and appeared in newspaper articles both in the US and in England after the war.36

Legacy

Following the war, US authorities received case files pertaining to the fate of the crew of the Strictly for Hunger from the French War Crimes Commission.37 The US Army conducted extensive interrogations in the towns of Schollach and Urach throughout the summer of 1945. They determined that Kuner and at least seven other Germans had buried the bodies of Mills, Radomski, Kornblau, Woolf, and Misiak in the forest surrounding Schollach in an attempt to cover up the murders. Seven months later, in February 1945, after outraged members of the community in Schollach discovered what had happened, the town pastor led an effort to secretly exhume the bodies and rebury them in the church cemetery.38 Following the interrogations in the summer of 1945, German police, working with the US Army, arrested seven men and charged them for the murders.39 A US military court in Dachau, Bavaria, Germany tried all seven.40 Kuner, who committed suicide in May 1945 after Nazi Germany’s collapse, was never tried.41 In April 1947, two of the seven German civilians who murdered the crew of the Strictly for Hunger received death sentences, three life terms in prison, and two twenty years’ imprisonment.42

Today, a memorial plaque near Schollach commemorates Leonard Kornblau and Bernard Radomski where they were slain in 1944.43 Additionally, on July 19th, 2014, to commemorate the seventieth anniversary of the murders, the communities of Schollach and Urach placed an ‘Atonement Cross’ in the forest between their towns, close to where the five servicemen’s bodies were originally buried. The cross, carved by German wood sculptor Wolfgang Kleiser, includes the names of Mills, Radomski, Kornblau, Woolf, and Misiak. Though the families of these Veterans have had their loved ones’ remains reinterred elsewhere since the war, to ensure that the memories of the American airmen who lost their lives on German soil are not forgotten, Kleiser sculpted the cross from the trunk of a North American Douglas Fir tree.44

SSgt. Mills’s service and sacrifice for his country earned him several medals and recognitions. To recognize former students and alumni who died during the war, UF published memorial pages in the 1945 and 1947 editions of their school yearbook; Meredith Mills, Jr. appears in both.45 The Air Medal with oak leaf cluster, which Mills earned after he completed between sixteen and eighteen missions, honors his heroism and meritorious acts during aerial flight.46 Mills also earned the Victory Medal for serving in World War II, and the Purple Heart for being killed in action.47 After they were exhumed from Schollach, SSgt. Mills’s remains were interred overseas in the US Military Cemetery in St. Avold, France, which later became the Lorraine American Cemetery and Memorial.48 In 1949, his parents chose to bring his remains home to Florida and have their son reinterred in the St. Augustine National Cemetery near his family. He rests among his fellow servicemen and women in Section D, Site 120.49

SSgt. Mills was survived by both of his parents. Meredith Mills, Sr. continued serving his community as the local pharmacist at least until 1950, with his wife Russie by his side.50 He passed away in 1969 and was laid to rest at Evergreen Cemetery on Rodriguez Street in St. Augustine, just two miles away from his son.51 Meredith Mills, Jr. and his father are remembered as World War Veterans and important members of their communities. Although their family line ended with their deaths, the Mills’s legacies of service and sacrifice continue to be memorialized through the cemeteries of St. Augustine, FL.

Endnotes

1 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” entry for Meredith M. Mills, St. Johns County, FL; “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Meredith M. Mills, Serial Number 14084813; “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Meredith Mills, St. Johns County, FL.

2 “Georgia, U.S., World War I Service Cards, 1917-1919,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Meredith M. Mills, Serial Number 719773; William C. Gaines, “Coast Artillery Organizational History, 1917-1950 Part 1, Coast Artillery Regiments 1-196,” The Coast Defense Journal 23, no. 2 (2004), 36-37, https://cdsg.org/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/FORTS/CACunits/CACreg1.pdf.

3 “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Russie Ware, Bradford County, FL.

4 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Meredith Mills, Deland City, Volusia County, FL.

5 “Many Students Take Pharmacists’ Exam,” Tampa Morning Tribune, June 7, 1923, 5A.

6 “1930 United States Federal Census.”

7 “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed July 23, 2023), entry for Meredith Mills, Volusia County, FL; “1940 United States Federal Census.”

8 “Florida in the 1920s: The Great Florida Land Boom,” Florida History, accessed July 29, 2023, http://floridahistory.org/landboom.htm.

9 Stanley K. Smith, “Florida Population Growth: Past, Present and Future,” Bureau of Economic and Business Research, June, 2005, 22 (accessed July 29, 2023), https://www.bebr.ufl.edu/sites/default/files/Research%20Reports/FloridaPop2005_0.pdf.

10 “The Great Depression in Florida,” Florida Department of State, 2023, accessed June 20, 2023, https://dos.myflorida.com/florida-facts/florida-history/a-brief-history/the-great-depression-in-florida/#:~:text=Florida%27s%20economic%20bubble%20burst%20in,1928%2C%20further%20damaging%20Florida%27s%20economy.

11 “Explorations: Children & the Great Depression,” Digital History, 2021, accessed July 23, 2023, https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/active_learning/explorations/children_depression/depression_children_menu.cfm.

12 “1930 United States Federal Census;” “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945.”

13 “1940 United States Federal Census.”

14 David Leonhardt, “Students of the Great Recession,” New York Times Magazine (New York, NY), May 7, 2010, accessed June 20, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/09/magazine/09fob-wwln-t.html#:~:text=In%201930%2C%20only%2030%20percent,t%20just%20make%20Americans%20tougher; “1940 United States Federal Census.”

15 University of Florida, The Seminole (Gainesville, FL: 1945), 144, University of Florida Digital Collections, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00022765/00036/images/143, accessed July 23, 2023.

16 University of Florida, The Seminole (Gainesville, FL: 1943), 237, University of Florida Digital Collections, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00022765/00034/images/236, accessed July 23, 2023.

17 “U.S, World War II Draft Registration Card;” “Battle of Midway,” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, accessed June 20, 2023, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/topics/battle-of-midway#:~:text=On%20the%20morning%20of%20June,facilities%20only%20suffered%20minor%20damage.

18 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records.”

19 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide: Preliminary Abridged Edition (St. Augustine, FL: St. Francis Barracks Special Archives, 1989), 211; “305th Bomb Group,” American Air Museum in Britain, May 18, 2023, accessed June 20, 2023, https://www.americanairmuseum.com/archive/unit/305th-bomb-group.

20 “305th Bomb Group.”

21 “365th Bomb Squadron,” American Air Museum in Britain, October 15, 2020, accessed June 20, 2023, https://www.americanairmuseum.com/archive/unit/365th-bomb-squadron.

22 “B-17G Flying Fortress,” Air Mobility Command Museum, June 23, 2021, accessed June 20, 2023, https://amcmuseum.org/at-the-museum/aircraft/b-17g-flying-fortress/.

23 C. Peter Chen, “B-17 Flying Fortress,” World War II Database, accessed July 18, 2023, https://ww2db.com/aircraft_spec.php?aircraft_model_id=4.

24 “U.S, World War II Draft Registration Card;” “Missing Air Crew Reports, WWII,” database, Fold3 (www.fold3.com: accessed July 18, 2023), entry for Meredith Mills.

25 “Gunners,” National Museum of the United States Air Force, accessed June 20, 2023, https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Visit/Museum-Exhibits/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/1519669/gunners/.

26 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide, 211; “Missing Air Crew Reports, WWII,” database, Fold3 (www.fold3.com: accessed August 2, 2023), entry for Edward A. Theed, Serial Number 34544025.

27 John Neider did not fly on the Strictly for Hunger’s final mission, and William E. Boyd is not pictured; “Missing Air Crew Reports, WWII,” entry for Meredith Mills; Irvin Hughes, “The Crew of Strictly for Hunger,” digital image, FindAGrave, added on June 4, 2021 by Jaap Vermeer, accessed August 9, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/102267424/bernard-e-radomski/photo#view-photo=229231031; Bernard Radomski is mistakenly identified as Benjamin in the photograph’s caption. UCF VLP would like to thank to Jaap Vermeer, Airwar Historian in the Netherlands, for allowing UCF VLP to use this image.

28 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide, 211.

29 “Missing Air Crew Reports, WWII,” entry for Meredith Mills.

30 “Cheektowagan Among 8 Fliers Slain by Nazis,” Buffalo Evening News, September 8, 1945, 35.

31 “Cheektowagan,” Buffalo Evening News.

32 Wolf Hockenjos, “Ein ‘Sühnekreuz’ für die am 21. Juli 1944 zwischen Schollach und Urach verübten Fliegermorde an amerikanischen Soldaten,” in Erinnern und Vergessen: Geschichten von Gedenkorten in der Region Schwarzwald-Baar-Heuberg, ed. Friedemann Kawohl (Donaueschingen, DE: Baar Verein, 2015), 247; UCF VLP wishes to thank Dr. Susanne Meinl, German historian and expert on Fliegermorde (‘Flyer-Murder’) cases and Jaap Vermeer, Airwar Historian in the Netherlands, for their assistance.

33 “Cheektowagan,” Buffalo Evening News.

34 “Cheektowagan,” Buffalo Evening News; Hockenjos, “Ein ‘Sühnekreuz’ für die am 21. Juli 1944 zwischen Schollach und Urach,” 247.

35 “Missing Air Crew Reports, WWII,” entry for Meredith Mills.

36 Information and figures in several newspaper articles conflict with information in other sources, including the Missing Air Crew Report for the Strictly for Hunger’s final mission. We verified the names of those airmen German civilians murdered and those sent to POW camps. There are inconsistencies in these sources regarding where each individual was killed, and whether there were other airmen from additional crashes murdered in the same areas; “Cheektowagan,” Buffalo Evening News;” “U.S. Airmen Beaten, Shot by Civilians,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 8, 1945, 8; “Murdered Airmen: Germans to Die,” Nottingham Evening Post, April 26, 1947, 1.

37 “Cheektowagan,” Buffalo Evening News.

38 Hockenjos, “Ein ‘Sühnekreuz’ für die am 21. Juli 1944 zwischen Schollach und Urach,” 247.

39 “Cheektowagan,” Buffalo Evening News.

40 Between November 1945 and December 1947, the US Army conducted war crimes trials for arrested German civilians, concentration camp guards, and Nazi soldiers at the site of the former Dachau Concentration Camp. This was done both because of the site’s ability to house the defendants and carry out the proceedings, as well as for its symbolic significance to the US Army’s prosecutions of Nazi and German war criminals immediately following the war; “The Dachau Trials: Background and Overview (1945-1947),” Jewish Virtual Library, accessed July 23, 2023, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/background-and-overview-of-the-dachau-trials.

41 Hockenjos, “Ein ‘Sühnekreuz’ für die am 21. Juli 1944 zwischen Schollach und Urach,” 247.

42 “Murdered Airmen: Germans to Die,” 1.

43 “UPL 34697 (Memorial Plaque for Leonard Kornblau and Bernard Radomski of the 305th Bomb Group,” American Air Museum in Britain, accessed June 20, 2023, https://www.americanairmuseum.com/archive/media/media-34697jpeg.

44 Hockenjos, “Ein ‘Sühnekreuz’ für die am 21. Juli 1944 zwischen Schollach und Urach,” 247.

45 University of Florida, The Seminole (Gainesville, FL: 1945), 144, University of Florida Digital Collections, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00022765/00036/images/143, accessed July 23, 2023; University of Florida, The Seminole (Gainesville, FL: 1947), 456, University of Florida Digital Collections, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00022765/00038/images/458, accessed July 23, 2023.

46 The bestowal of an oak leaf cluster denotes an additional award of the same decoration, see “Air Medal Certificate: First Oak Leaf Cluster,” The Vietnam Memory Project, U.S. Air Force, accessed June 20, 2023, https://musselmanlibrary.org/vietnam-memory/items/show/28; “Missing Air Crew Reports, WWII,” database, Fold3 (www.fold3.com: accessed August 4, 2023), entry for Meredith M. Mills, Jr., Serial Number 14084183.

47 Danielle DeSimone, “9 Things You Need to Know about the Purple Heart Medal,” United Service Organizations, August 1, 2022, accessed June 20, 2023, https://www.uso.org/stories/2276-8-purple-heart-facts#:~:text=The%20Purple%20Heart%20medal%20is,in%20the%20line%20of%20duty.

48 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide, 211; “Lorraine American Cemetery: Overview,” American Battle Monuments Commission, https://www.abmc.gov/Lorraine.

49 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 18, 2023), entry for Meredith M. Mills.

50 “1950 U.S. Census,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Meredith Mills, St. Johns County, Florida.

51 “U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1861-1985,” database, Ancestry (www.ancestry.com: accessed June 15, 2023), entry for Meredith M. Mills, St. Johns County, Florida.

© 2023, University of Central Florida