Grady M. Walters Jr. (October 2, 1919-November 26, 1943)

51st Base Headquarters and Air Base Squadron, 1st Proving Ground Group

By Whitney Yount and John Lancaster

Early Life

Grady M. Walters Jr. was born on October 2, 1919, in Laurens County, GA, the first child of Grady M. Walters Sr. and Estoria (née Lawrence) Walters.1 In 1920, the new family lived in a house they rented on Sawyer St., in Dublin, GA, where Grady Sr. worked as an automobile mechanic.2 Grady Sr., born January 24, 1892 in Washington County, GA, grew up in a farming family.3 In 1900, he lived with his parents, grandmother, and older brother Fred on a farm his family rented and cultivated.4 Ten years later, he lived with Fred and Fred’s family on another farm in Montgomery County, GA, where he worked as a farm laborer.5 Sometime before 1917, Grady Sr. left his brother’s farm and began working as a mechanic.6 Around this time, he met Estoria Lawrence, a fellow Georgia native. The two married in Laurens County, GA on March 18, 1918.7

The First World War broke out in Europe in the summer of 1914. Although initially committed to American neutrality throughout the first years of the war, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany in April 1917, officially entering the US into the conflict.8 On May 18, 1917, in order to quickly mobilize for the war effort, Congress passed the Selective Service Act. This act, which by 1918 expanded to require all men between the ages of twenty-one and forty-five to register for military service, laid the groundwork for the US military to call nearly three million people into the armed forces throughout the war.9 On June 5, 1917, Grady Sr. registered for the draft in Wheeler County, GA.10 One year later, on June 8, 1918, the US military called Grady Sr. into service. He reported to Fort Screven, located on Tybee Island, GA, for induction.11 He served as a mechanic with Company H, 43rd Infantry throughout the final months of the war, but never deployed overseas. The military granted him an honorable discharge from duty on December 26, 1918.12 For his service, Grady Sr. applied for the Victory Medal on September 20, 1920. The government awarded this medal to US Veterans who served during America’s involvement in World War I.13

Following Grady Jr.’s birth on October 2, 1919, the family moved to Andalusia, AL, where Grady Sr. and Estoria welcomed their second son, William Albert, on September 25, 1925.14 The Great Depression, which began after the stock market collapsed in October 1929, severely affected the US economy and the personal finances of millions of Americans. Around this time, the Walters family moved again, to Jacksonville, FL. Despite Grady Sr.’s continued employment as an automobile mechanic, in 1930 the family of four lived as boarders in a rooming house, managed by Pearl Jackson, on East Monroe St. in Jacksonville. Likely due to the economic difficulties of the period, the Walters family lived there with at least seven other families.15 In 1930, about 3.8 million people lived as roomers or boarders in the US, comprising three percent of the total population.16 By 1935, the Walters family had moved out of Pearl Jackson’s rooming house and into a home they rented in St. Augustine, FL.17 Grady Jr. and his brother, William Albert, attended school despite the economic hardships. They both completed four years of high school, an impressive accomplishment at a time when only about thirty percent of American teenagers graduated with high school diplomas.18

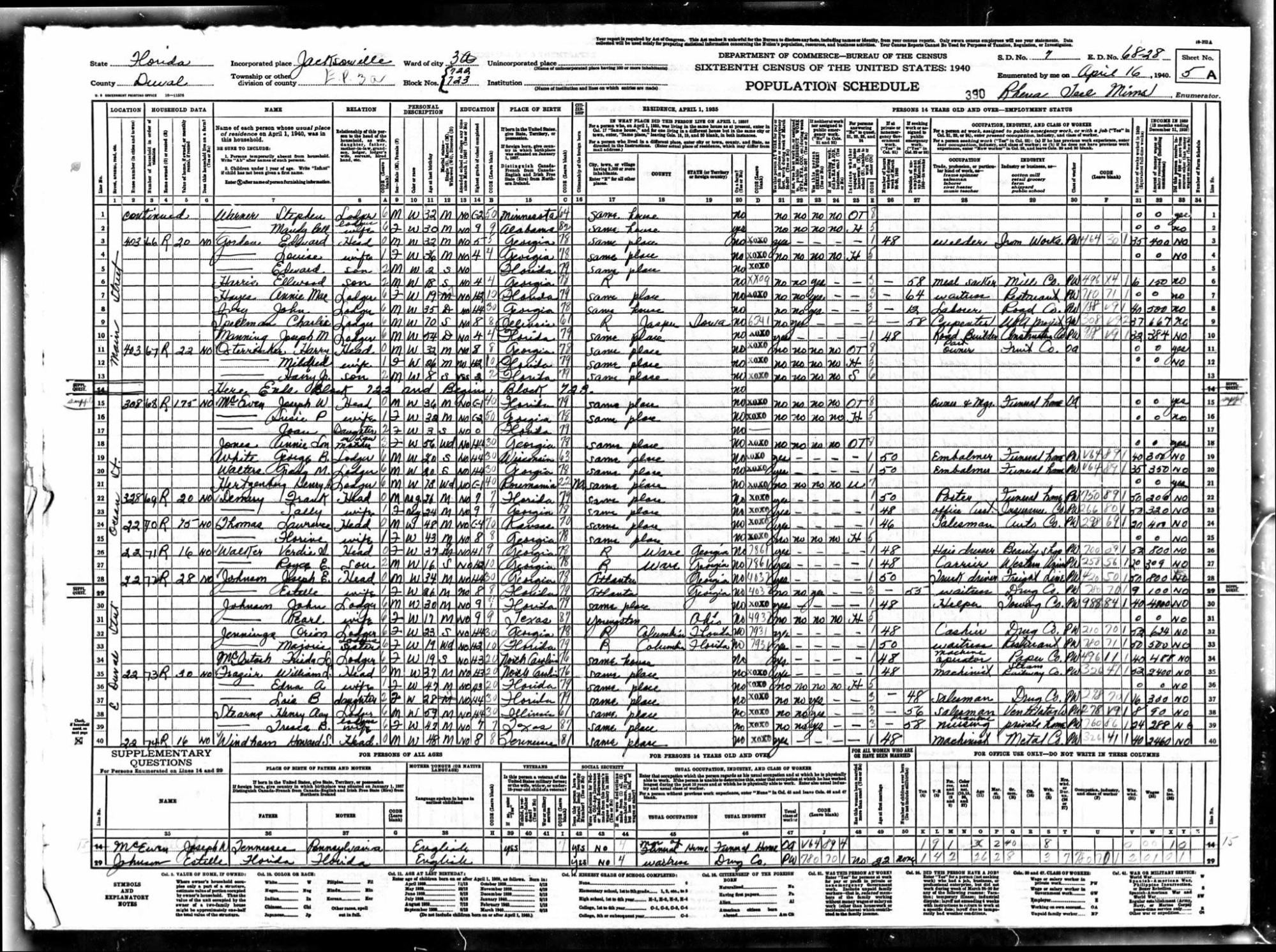

By 1940, Grady Jr. no longer lived with his parents and brother, but had moved back to Jacksonville, where he worked as an embalmer for a funeral home. He lived as a lodger, along with two other men, in the home of Joseph W. McEven, who owned and managed a funeral home in Jacksonville. As an apprentice mortician, Grady Jr. worked fifty hours a week in 1940 for McEven’s funeral home, seen on the federal census record here.19 While Grady Jr. lived and worked in Jacksonville, the rest of his family remained in St. Augustine. In 1940, Grady Sr. worked as a mechanic at Bill Smith Garage in St. Augustine, providing for his wife, Estoria, son, William Albert, and a niece, Eddie May, who had moved in with the family. Eddie May worked as a switchboard operator for the telephone company. The four lived together in a home the family rented on Alfred St.20

Military Service

On September 19, 1940, Grady Walters Jr. enlisted in the US Army Air Corps in Jacksonville.21 Though the US did not officially join the Second World War until December 1941, following the Japanese surprise attack at Pearl Harbor, HI, the government worked to prepare and expand the nation’s military capabilities preceding its entrance into the war. For instance, in June 1940, the Department of Agriculture transferred nearly 400,000 acres of land then constituting part of the Choctawhatchee National Forest, in the western Florida panhandle, to the War Department. With this land, the military expanded nearby Eglin Field into an Army Air Corps Proving Ground. Here, US Army personnel tested aircraft armament, equipment, and flying techniques in preparation for aerial combat.22 After his initial training, Grady Jr. reported to Eglin Field, where he served as part of the 51st Base Headquarters and Air Base Squadron, 1st Proving Ground Group.23

Grady Jr. served as the Chief Clerk of Operations at Eglin Field for two and a half years, and eventually reached the rank of Staff Sergeant in this role.24 His responsibilities as Chief Clerk of Operations included supervising clerical personnel, compiling and organizing records and reports, responding to requests for records, and maintaining important military documents pertaining to Army personnel.25

In October 1943, Grady Jr. deployed overseas to the African area of operations.26 In late November 1943, he boarded the HMT Rohna, a British transport ship, alongside ninety-two Allied officers, seven American Red Cross representatives, and nearly two thousand other enlisted men of the US Army.27 The ship departed from Oran, Algeria on November 26, en route to British India via the Mediterranean Sea. A passenger liner before the war and only recently requisitioned for military service, the Rohna carried more than twice its standard occupancy when it set sail.28

Shortly after 5:00 p.m., as the HMT Rohna passed about fifteen miles north of the Algerian coastal city of Djidjelli (now Jijel), more than thirty German Luftwaffe planes attacked the ship and its convoy. During the first wave of the assault, enemy bombers failed to cause significant damage to the Rohna, held off by escort vessels in the ship’s convoy. After multiple passes by German aircraft, however, a Luftwaffe bomber released a Henschel HS-293 missile from under its wing toward the Rohna.29 A radio-controlled, rocket-propelled glide bomb first employed by the Germans just three months earlier, in August 1943, the HS-293 became the first guided bomb used in combat.30 The bomb struck the engine room of the Rohna, causing massive damage and casualties upon impact and detonation. The engine room quickly flooded, destroying all of the ship’s electrical equipment. Though the crew attempted to abandon the ship, the Rohna sank quickly. Its bow disappeared below the surface of the Mediterranean at approximately 7:00 p.m., less than two hours after the German aerial attack.31

Six rescue ships, all traveling as part of the escort convoy, worked through the night to rescue survivors from the water.32 One, the USS Pioneer, saved over six hundred people. In total, 1,149 crew and passengers died during the attack, including 1,015 US service members. An additional thirty-five US Army Veterans later died from wounds they received during the assault.33 Though brought to a hospital after the attack, Grady M. Walters Jr. died from injuries he suffered aboard the Rohna on the night of November 26, 1943.34 The sinking of HMT Rohna remains the greatest loss of US life at sea due to enemy action.35

Legacy

Despite the significant loss of life, the sinking of HMT Rohna remains obscured. The British and American militaries classified the incident, and in the years after the attack attempted to conceal its history. Though military officials initially claimed that the Rohna contained an adequate supply of life-preserving equipment, later investigations determined that a number of the ship’s lifeboats and lifebelts did not function properly, likely contributing to the large loss of life.36 Additionally, Allied governments may not have wanted to report on new German technology like the HS-293 guided bomb, which sank the Rohna.

Perhaps in part due to this classification, the War Department initially listed Grady Jr. as Missing in Action (MIA). In January 1944, American newspapers reported that Grady Jr. remained MIA in the Mediterranean area.37 Grady Jr.’s family and loved ones did not learn about his death until February, three months after the attack on the Rohna.38

Today, Grady Jr.’s legacy endures as part of the increasing desire to illuminate the story of the ship and the terrible loss of life that occurred on it. In November 1993, as part of his Veterans Day address, CBS News commentator Charles Osgood directly referenced the HMT Rohna, sunk fifty years earlier. Osgood’s remarks helped bring the incident to light throughout the subsequent decade. On May 30, 1996, the newly-organized Rohna Survivors Memorial Association dedicated a plaque to the over one thousand US servicemen who died during the incident. The plaque stands in Fort Mitchell National Cemetery, in Seale, AL.39 Additionally, on September 12, 2000, Congressman Jack Metcalf of Washington State gave a speech on the floor of the US House of Representatives entitled, “Remembering the Sinking of the HMT Rohna.” A month later, on October 27, Metcalf helped pass House Concurrent Resolution 408, which officially recognized and memorialized the legacy of the attack on the Rohna.40 These memorials and dedications ensure the stories of fallen heroes like SSgt. Grady M. Walters Jr. and all those who died in the attack on the Rohna continue to inspire future generations.

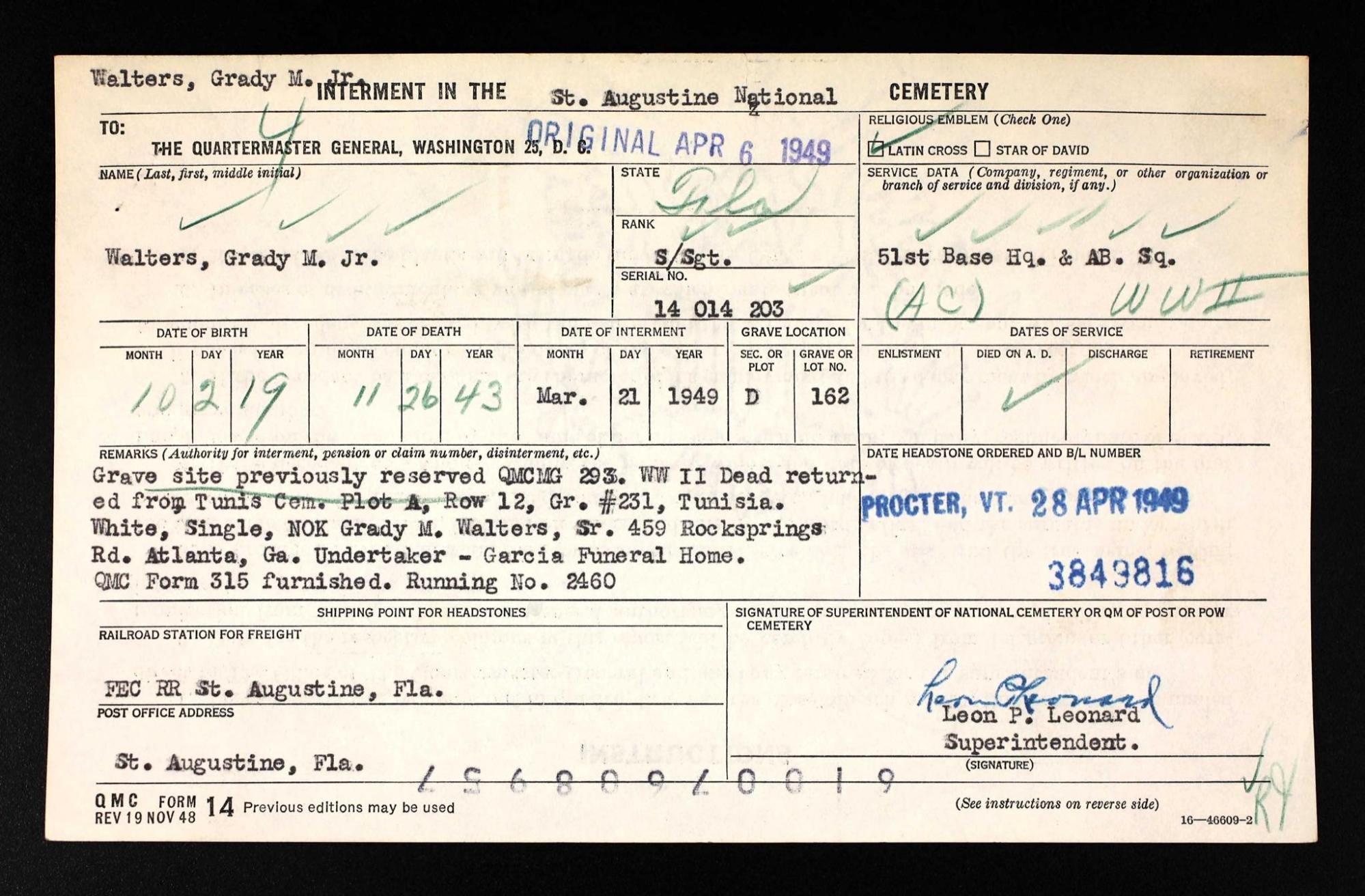

Grady Jr.’s comrades initially buried him in a temporary cemetery in Tunis, Tunisia, seen on the interment record here.41 The cemetery existed near the present site of the American Battle Monuments Commission’s North Africa American Cemetery and Memorial, now in Carthage. Today, Tablets of the Missing at the North Africa American Cemetery and Memorial bear the names of over 3,700 service members who remain missing from the African and Mediterranean areas, including many from the Rohna.42 In January 1949, while Grady Jr. remained in Tunis, Dr. Rufus Wicker, pastor of Druid Hills Methodist Church in Atlanta, dedicated a framed picture of Grady Jr. and ten other Veterans killed in the Second World War during his service.43

Following the war, the US government instituted the Return of World War II Dead Program. This program allowed the families of Veterans killed overseas to repatriate their loved one’s remains to the US, if they wished, so they could rest closer to home.44 In March 1949, Grady Sr., as his son’s next of kin, decided to bring Grady Jr. back to Florida. Though Grady Sr., Estoria, William Albert, and Eddie May lived together in Fulton County, GA in 1950, they elected to bury Grady Jr. in St. Augustine, FL, where the family had lived together in the 1930s.45 Grady M. Walters Jr. now rests at St. Augustine National Cemetery among his fellow Veterans in Section D, Plot 162.46

Endnotes

1 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 17, 2024), entry for Grady M Walters II; “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Grady M Walters, Laurens County, GA; some sources record Estoria’s name as Estora, but this biography uses the name Estoria as this is the name that appears on her headstone.

2 “1920 United States Federal Census,” entry for Grady M Walters, Laurens County, GA.

3 “Grady McBride Walters,” FindAGrave, May 16, 2012, accessed July 30, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/90208626/grady-mcbride-walters?_gl=1*catjc2*_gcl_au*ODIwNzMxMjYuMTcyMTE0MzExMw..*_ga*MjE4MDM4NjQzLjE3MjExNDMxMTQ.*_ga_4QT8FMEX30*NmI3ZWQzZmItMmNjMy00YjA3LThkZDYtMDc0MmU3N2M0MDM1LjEyLjEuMTcyMjM1MjI5MC4yMC4wLjA.*_ga_LMK6K2LSJH*NmI3ZWQzZmItMmNjMy00YjA3LThkZDYtMDc0MmU3N2M0MDM1LjEyLjEuMTcyMjM1MjI5MC4wLjAuMA.

4 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for G W Walters, Washington County, GA.

5 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Grady M Walters Jr, Montgomery County, GA.

6 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 17, 2024), entry for Grady McBrid Walters.

7 “Georgia, U.S., Marriage Records from Select Counties, 1828-1978,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 17, 2024), entry for Grady Watters.

8 “U.S. Entry into World War I, 1917,” Office of the Historian, US Department of State, accessed July 30, 2024, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1914-1920/wwi#:~:text=On%20April%204%2C%201917%2C%20the,Hungary%20on%20December%207%2C%201917.

9 “Mobilizing for War: The Selective Service Act in World War I,” National Archives Foundation, accessed July 30, 2024, https://www.archivesfoundation.org/documents/mobilizing-war-selective-service-act-world-war/#:~:text=On%20May%2018%2C%201917%2C%20Congress,to%20register%20for%20military%20service.

10 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” entry for Grady McBrid Walters.

11 “U.S., Lists of Men Ordered to Report to Local Board for Military Duty, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 17, 2024), entry for Grady M Walters.

12 “Georgia, U.S., World War I Service Cards, 1917-1919,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 17, 2024), entry for Grady M Walters.

13 “Georgia, U.S., World War I Service Cards, 1917-1919,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 17, 2024), entry for Grady McBride Walters; “Medal, World War I Victory Medal,” Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, accessed July 30, 2024, https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/medal-world-war-i-victory-medal/nasm_A19751591000.

14 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 17, 2024), entry for William Albert Walters; “W. Albert Walters,” FindAGrave, July 3, 2008, accessed July 30, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/28010364/w.-albert-walters?_gl=1*pmi24x*_gcl_au*ODIwNzMxMjYuMTcyMTE0MzExMw..*_ga*MjE4MDM4NjQzLjE3MjExNDMxMTQ.*_ga_4QT8FMEX30*NmI3ZWQzZmItMmNjMy00YjA3LThkZDYtMDc0MmU3N2M0MDM1LjEyLjEuMTcyMjM1Njg5Ny4yMy4wLjA.*_ga_LMK6K2LSJH*NmI3ZWQzZmItMmNjMy00YjA3LThkZDYtMDc0MmU3N2M0MDM1LjEyLjEuMTcyMjM1Njg5Ny4wLjAuMA.

15 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Grady Walters, Duval County, FL.

16 Melissa Scopilliti and Martin O’Connell, “Roomers and Boarders: 1880-2005,” (paper presented at Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, New Orleans, LA, April 17-19, 2008), 1, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2008/demo/scopilliti-oconnell-paa-2008.pdf.

17 “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945 ,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Grady Walters, St. Johns County, FL.

18 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Grady M Walters, Duval County, FL; “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for William A Walters; David Leonhardt, “Students of the Great Recession,” New York Times Magazine (New York, NY), May 7, 2010, accessed July 30, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/09/magazine/09fob-wwln-t.html.

19 “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for Grady M Walters; “Sgt. G. M. Walters Dies of Injuries,” Atlanta Journal, February 18, 1944, 20.

20 “Ohio and Florida, U.S., City Directories, 1902-1960,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Grady M Walters, St. Augustine, St. Johns County, FL; “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Grady M Walters, St. Johns County, FL.

21 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Grady MCB Walters.

22 SSgt Yancy D. Mailes, “Eglin AFB Base Operating Units 1935-2000,” Eglin Air Force Base, 5-6, https://www.eglin.af.mil/Portals/56/documents/history/AFD-141104-074.pdf.

23 Mailes, “Eglin AFB Base Operating Units 1935-2000,” 8, https://www.eglin.af.mil/Portals/56/documents/history/AFD-141104-074.pdf; “Sgt. G. M. Walters Dies of Injuries,” Atlanta Journal, February 18, 1944, 20.

24 “Sgt. G. M. Walters Dies of Injuries,” Atlanta Journal, February 18, 1944, 20.

25 “Military Personnel Clerical and Technician Series,” United States Office of Personnel Management, July 1999, 4, https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/classification-qualifications/classifying-general-schedule-positions/standards/0200/gs0204.pdf.

26 “Sgt. G. M. Walters Dies of Injuries,” Atlanta Journal, February 18, 1944, 20.

27 “Review and Determination of Status of Casualties Incurred in the Sinking of SS ‘ROHNA’ in the Mediterranean Sea on 26 November 1943,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed April 29, 2024), entry for Rohna, page 1.

28 “The Sinking of the HMT Rohna,” The National WWII Museum New Orleans, November 17, 2023, accessed July 30, 2024, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/sinking-hmt-rohna.

29 “Review and Determination of Status of Casualties Incurred in the Sinking of SS ‘ROHNA’ in the Mediterranean Sea on 26 November 1943,” entry for Rohna; “The Sinking of the HMT Rohna,” The National WWII Museum New Orleans, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/sinking-hmt-rohna.

30 “Hitler’s Precision-Guided Bombs: Fritz-X & Hs 293,” The National WWII Museum New Orleans, September 21, 2023, accessed July 30, 2024, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/hitlers-precision-guided-bombs-fritz-x-hs-293.

31 “Review and Determination of Status of Casualties Incurred in the Sinking of SS ‘ROHNA’ in the Mediterranean Sea on 26 November 1943,” entry for Rohna, page 1.

32 “Review and Determination of Status of Casualties Incurred in the Sinking of SS ‘ROHNA’ in the Mediterranean Sea on 26 November 1943,” entry for Rohna, page 1.

33 “H-Gram 022: Spanish Influenza Epidemic, Loss of British Transport HMT Rohna, Operation Leader, Loss of USS Wahoo, Battle of Vella Lavella, Operation Rolling Thunder Ends,” Naval History and Heritage Command, October 31, 2018, accessed July 30, 2024, https://www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-022.html#2; “Casualties,” The Rohna Survivors Memorial Association,” accessed July 30, 2024, https://rohnasurvivors.org/casualties/.

34 “US, WWII Army and Army Air Force Casualty List, 1946,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed April 29, 2024), entry for Walters, Grady M., service number 14014203.

35 “The Story,” Rohna Classified, accessed July 31, 2024, https://www.rohnaclassified.com/; “H-Gram 022: Spanish Influenza Epidemic, Loss of British Transport HMT Rohna, Operation Leader, Loss of USS Wahoo, Battle of Vella Lavella, Operation Rolling Thunder Ends,” Naval History and Heritage Command, https://www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-022.html#2.

36 “Review and Determination of Status of Casualties Incurred in the Sinking of SS ‘ROHNA’ in the Mediterranean Sea on 26 November 1943,” entry for Rohna, page 2; “The Story,” Rohna Classified, https://www.rohnaclassified.com/.

37 “Six Georgians Missing in Action–Two Wounded,” Atlanta Journal, January 19, 1944, 1; “Three Floridians Missing in Action,” Tampa Times, January 19,1944, 2; “1 Killed, 4 Lost, 13 Hurt in War,” Atlanta Constitution, January 23, 1944, 12.

38 “Sgt. G. M. Walters Dies of Injuries,” Atlanta Journal, February 18, 1944, 20.

39 “The Memorial,” The Rohna Survivors Memorial Association, accessed July 31, 2024, https://rohnasurvivors.org/the-memorial/; “The Sinking of the HMT Rohna,” The National WWII Museum New Orleans, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/sinking-hmt-rohna.

40 Congressional Recognition,” The Rohna Survivors Memorial Association, accessed July 31, 2024, https://rohnasurvivors.org/congressional-recognition/.

41 U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for Grady M Walters II.

42 “North Africa American Cemetery,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed July 31, 2024, https://www.abmc.gov/multimedia/videos/north-africa-american-cemetery#:~:text=Beneath%20a%20canopy%20of%20trees,polished%20marble%20and%20Moroccan%20cedar; “North Africa American Cemetery and Memorial,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed July 31, 2024, https://www.abmc.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/North%20Africa%20American%20Cemetery%20and%20Memorial%20%282019%20brochure%29.pdf.

43 “War Dead Dedication,” Atlanta Journal, January 1, 1949, 7.

44 “America’s World War II Burial Program,” US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration, accessed May 31, 2024, https://www.cem.va.gov/docs/wcag/history/WWII-Burial-Program-America.pdf, 4-5.

45 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 21, 2024), entry for Grady M Walters, Fulton County, GA; “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for Grady M Walters II.

46 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for Grady M Walters II.

© 2024, University of Central Florida