Francis T. Piet Jr. (February 20, 1925–January 24, 1945)

Torpedo Squadron 80, Carrier Air Group 80, USS Ticonderoga

By Levi Berry and Jim Stoddard

Early Life

Francis T. Piet Jr. was born on February 20, 1925 in St. Augustine, FL to Antonica “Neca” and Francis Piet Sr.1 His mother, Neca, was born in Florida in 1902 as Antonica Maria Reyes.2 Francis Sr. was born in Haarlem, Holland as Franciscus Piet on March 27, 1896. Neca’s father also hailed from Holland, which may, at least in part, explain how they met.3 At the age of thirteen, Franciscus and his family immigrated to the US aboard the SS Rotterdam and arrived at Hoboken, NJ on August 5, 1909.4 In the years following his arrival in America, Franciscus adopted the Anglicized name Francis, and often went by Frank.5 Migration patterns dating back to the 1880s likely influenced Francis and his parents to come to the US. The Netherlands experienced an agricultural crisis in the 1880s that brought around 75,000 Dutch citizens to America in the decades before the twentieth century. Another 75,000 came to the US between 1900 and 1914 alone, including Francis and his family.6 After the Piets arrived in the US, they settled in Jacksonville, FL, where at fourteen years old Francis worked as a cash boy in a dry goods store.7

On June 5, 1917, two months after the US joined World War I, Francis registered for the draft in Jacksonville, FL.8 Although he never served in the military, many new immigrants to the US served during the First World War. In an effort to encourage immigrants to enlist, Congress passed the Alien Naturalization Act of May 9, 1918, which made the path to citizenship easier for those who had served.9 Just months earlier, on December 15, 1917, Francis applied to become a citizen of the US. At the time, he worked as a multigraph operator.10 A multigraph was an early version of the modern copy machine.11 Three years later, on December 7, 1920, the government approved Francis’s naturalization petition and granted him US citizenship.12

Francis married Antonica Maria Reyes on April 21, 1924.13 On February 20, 1925, they welcomed their first son, Francis Jr. By 1930, the Piets had relocated to St. Augustine, FL, where they continued to expand their family. At the time, the family lived in a rented home on Cordova Street, in the historic center of St. Augustine.14 Francis Jr. completed at least one year of high school by 1940 and was the oldest of six sons alongside Edward (born 1927), Ralph (born 1928), Joseph (born 1930), Louis (born 1935), and Laurence (born 1937).15 Francis Jr. grew up during the Great Depression, when the American cost of living averaged around $4,000 per year and yearly income averaged $1,125. Working as a linotype operator for a newspaper in 1940, Francis Sr. earned $1,900 a year to provide for his family. Still, the family managed to live in a home they owned on Saragossa Street, in downtown St. Augustine, by 1940.16

Military Service

Francis likely entered the US Navy sometime after he registered for the draft in February 1943.17 After his induction and initial naval training, Francis trained as an aviation radioman for the Grumman Torpedo Bomber (TBF) Avenger torpedo dive bomber.18 During the World War II era, aviation radiomen trained for eighteen weeks in Memphis, TN. Over that period they learned how to operate and maintain aircraft radios and radar systems. From there, Avenger radiomen trainees moved to Jacksonville, FL and received two weeks of machine training and eight weeks of naval dive bomber flight training. An average day had them fly three hours in the morning and three hours in the afternoon.19 In addition to the training, the Navy required aviation radiomen to meet certain physical standards, such as 20/20 vision, 15/15 hearing by whispered voice, and a passing score on the Pseudo Isochromatic Plates for Testing Color Perception test.20

As an aviation radioman aboard an Avenger, Francis transmitted and received messages, encrypted and decrypted codes, made radio repairs, and used a radio-telephone. When under attack from enemy aircraft, he operated a rear-facing machine gun from his position on the bottom of the plane. During bombing runs, he armed and ensured the release of the aircraft’s ordnance. Undropped live ordnance, including bombs, torpedoes, missiles, or rockets could explode upon the aircraft’s landing, so ensuring they dropped or released remained essential. This task consisted of looking down through the open bay doors as the plane flew in order to both track the release of the ordnance and collect potentially useful intelligence from the ground below. As part of this incredibly dangerous and vital work, Francis recorded everything about a mission on a pad of paper strapped to his leg, secured so it could not fly away as he stood in the belly of the plane amid the rushing winds of the open bay doors. His mission notes proved vital to flight debriefs, intelligence reports, and future mission planning as he would have included what he could see on the ground in enemy territory.21

The Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation developed the TBF Avenger torpedo bomber, first used in combat during the Battle of Midway in 1942.22 The plane had a large bomb bay that allowed for one torpedo and either a 2006-lb bomb or four 496-lb bombs. Because it had docile handling, good radio facilities, a high flight ceiling (30,000 ft), and long range (994 miles when fully loaded), flight leaders saw the Avenger as an ideal command aircraft for Carrier Air Groups (CAGs), especially with the distances planes flew over the open ocean in the Pacific Theater. CAGs constituted the aircraft elements assigned to deploy from aircraft carriers. Because of its combat capability and multi-use role, the Avenger became America’s most potent torpedo bomber of World War II.23

After completing his training and qualifying as an aviation radioman, the Navy assigned Francis to torpedo bomber squadron VT-80, CAG-80.24 CAG-80 also contained five other squadrons with fighter and bomber aircraft. CAG-80 flew from the brand new Essex-class aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga (CV-14).25 The Navy commissioned her in May 1944 in Norfolk, VA with Captain Dixie Kiefer in command.26 With the ultimate destination the Pacific Theater of Operations, Francis and the Ticonderoga departed Virginia on June 30, 1944. They spent fifteen days of intensive training at the Port of Spain, Trinidad, to weld both the ship and crew together into an efficient wartime team. The Ticonderoga passed through the Panama Canal on September 4 and steamed up the coast to San Diego, CA the following day. She left for Hawaii on September 19 and arrived five days later at Pearl Harbor. The Ticonderoga left Pearl Harbor on October 18 and arrived at Ulithi, an atoll in the Western Caroline Islands located north of New Guinea, eleven days later on October 29, where it joined Naval Task Force (TF)-38.27

The Tico, as her crew sometimes called her, left on November 2 and joined the other carriers in extended air cover for ground forces during the Battle of Leyte, in the Philippines. Francis and the aircrew of CAG-80 launched their first air strike on the morning of November 5, 1944. Over the course of the battle, Francis’ group bombed enemy air installations on several of the the Philippine islands and sunk the Imperial Japanese Navy heavy cruiser, Nachi. Pilots flying from the Tico destroyed forty-three Japanese aircraft and damaged twenty-three others. The enemy retaliated with kamikaze planes. Fortunately for TF-38, only one slipped through American air patrol and anti-aircraft fire to crash into the USS Lexington.28

Francis and the rest of TF-38 attacked a Japanese reinforcement convoy on November 11. They destroyed the Japanese light cruiser Kiso, four destroyers, and seven merchant ships. TF-38 supported combat operations in the Philippines throughout November and December 1944, and used Ulithi as a refueling and rearming depot. During a December 16 return to Ulithi, TF-38 unknowingly sailed straight for a violent typhoon. The typhoon sank three of the task force’s destroyers and claimed over 800 lives. The Ticonderoga and the rest of the carriers managed to ride out the storm with minimal damage. TF-38 finally arrived in Ulithi on December 24.29

TF-38 returned to combat and struck Luzon again on January 6, 1945, and, despite heavy weather, destroyed thirty-two enemy aircraft. Terrible weather conditions prevented TF-38 from further attacks over the next few days. The sailors of the task force considered bad weather “the bugaboo of TF-38 during the winter of 1944 and 1945.”30 On January 9-10, TF-38 moved through the Luzon Strait, between the islands of Luzon and Formosa (modern day Taiwan), and then headed southwest, across the South China Sea.31 The task force then sat off the coast of Indochina where its aircraft impeded Japanese shipping. Francis and his fellow aviators sank forty-four enemy vessels during this period.32

On January 21, TF-38 sailed northeast to the coast of the Japanese-held island of Formosa and commenced airstrikes on enemy positions. Just after noon, a Japanese kamikaze plane crashed into the flight deck on the port side of the USS Ticonderoga. Photographers onboard captured the event on film, as seen here.33 Shortly after impact, the plane’s bomb exploded just above the hangar deck. The explosion killed and injured many sailors and set several planes on fire. The ship’s crew fought the fire while Captain Kiefer changed the course of the ship to keep the wind from fanning the flames. He ordered multiple compartments of the ship flooded to douse the fire. The flooding dumped the fire overboard and firefighters finished the job; however, more kamikazes targeted the Ticonderoga throughout that afternoon. The ship’s anti-aircraft gun crews managed to shoot three down, but the fourth one made it through their fire. The Japanese aircraft crashed into the Ticonderoga’s starboard side, exploded, and set the ship ablaze once more. This second strike killed many more of the crew and injured Captain Kiefer. For a second time, the crew fought to extinguish the fires on board. The two kamikaze strikes killed over one hundred of the Ticonderoga’s crew and injured many more.34

While the crew of the Ticonderoga defended their ship, Francis and the aircrew of VT-80 attacked enemy ships in Formosa’s Toshien Harbor. Francis flew in the lead aircraft, piloted by Lieutenant (Lt.) S.B. Smith. Lt. Smith led his flight of twelve Avengers above the clouds from east to west, which kept the sun at their backs in an effort to complicate enemy pilots’ lines of sight. The American pilots dove their aircraft from an altitude of 6,000 ft to release their ordnance. Over a series of attack runs, the aircrew of VT-80 dropped seventy-five bombs and fired thirty rockets at nine enemy targets in the harbor. Once the attack began, Japanese anti-aircraft fire opened up on the Avengers, which forced the pilots to take “violent evasive action” to avoid taking damage.35

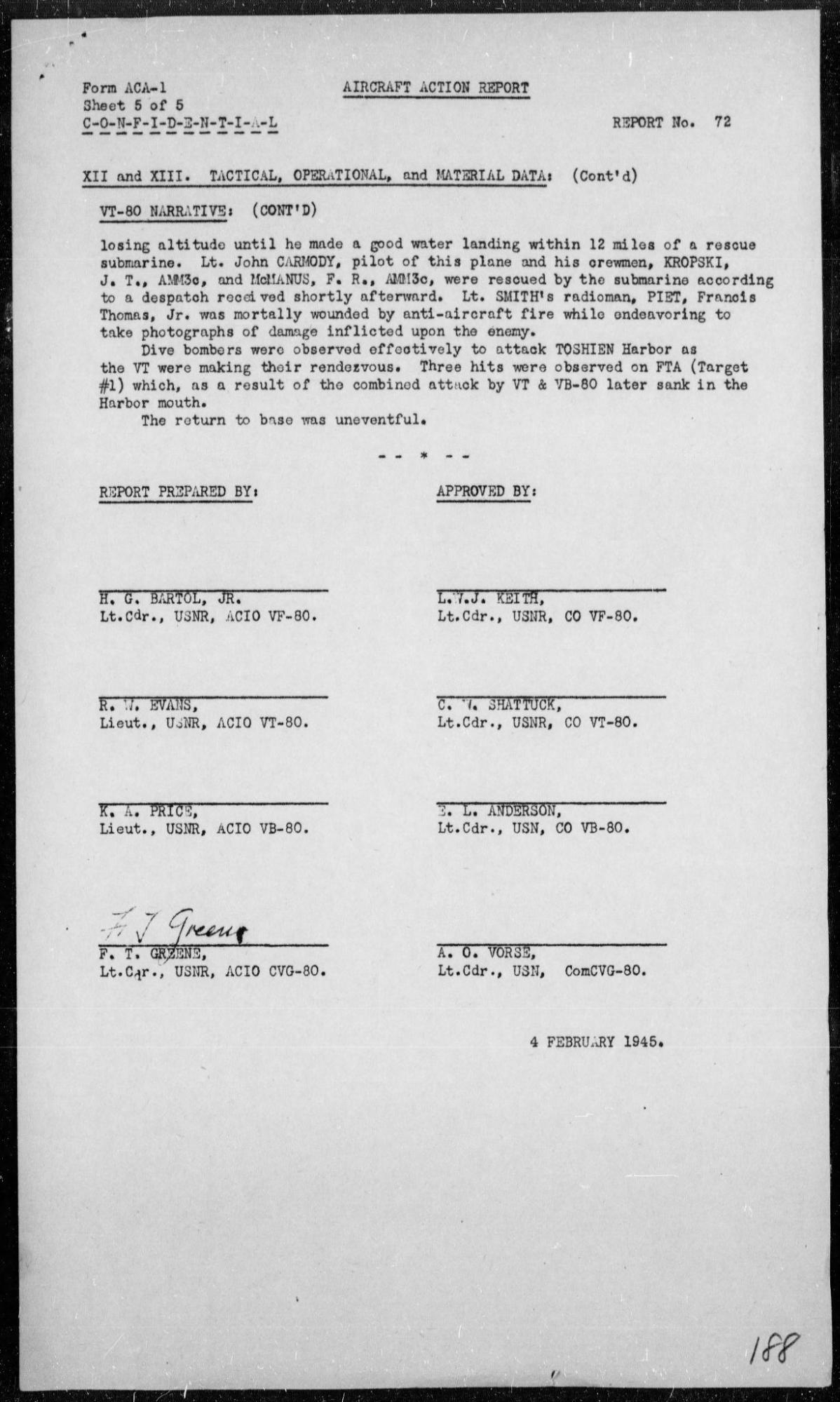

Despite the pilots’ best efforts, anti-aircraft fire hit three of the Avengers. Two suffered only light damage, but the third caught fire, which forced its pilot to ditch in the ocean. All three aircrew aboard this third plane survived and a nearby submarine rescued them. Francis, flying in one of the lightly damaged Avengers, unfortunately suffered severe injuries. An anti-aircraft round penetrated the plane, struck Francis in the head, and mortally wounded him, as noted in the report pictured here. Upon landing on the Ticonderoga, medical crews brought Francis to the ship’s medical facilities, where he remained for three days.36 The USS Samaritan, a hospital ship, took Francis aboard on January 24, following the battle.37 Despite the medical crew’s best efforts, Francis Thomas Piet Jr. died of his wounds later that day. The Samaritan brought his remains back to Ulithi, where he was temporarily interred on January 25, 1945.38

Legacy

Francis Piet and CAG-80 thwarted Japanese efforts to maintain dominance over East Asia and destroyed military shipping, vessels, and aircraft. After the kamikaze attack, the badly damaged Ticonderoga traveled back to Ulithi to move her air group to the USS Hancock, her wounded to the USS Samaritan, and to embark passengers bound for home. The carrier arrived at the Puget Sound Navy Yard, in Washington State, for repairs on February 15, 1945. Maintainers completed her repairs and the Ticonderoga sailed on April 20, 1945, to rejoin TF-38 as an element in the Japan Campaign.39 Since its service in the Second World War, the Ticonderoga has garnered a number of memorializations. In 1944, Eddie Fritz Jr., who served aboard the Ticonderoga, wrote a song dedicated to the ship. Named Ticonderoga - The Big “T,” musician Mark Wolfram adapted Fritz’s lyrics for concert band and male chorus in 1974, and the song continues to serve as a fitting dedication to the men who served aboard the Ticonderoga during World War II.40 Additionally, a memorial to the ship and its members today lives at the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, TX, and a memorial to United States Aircraft Carriers and crews, including the Ticonderoga and her crew, lives in central San Diego.41

In the years following the war, Francis Sr. continued to work as a linotype operator.42 He passed away on December 19, 1963, at the age of sixty-seven.43 His wife Neca passed away on January 14, 1979, and now rests beside her husband in San Lorenzo Cemetery in St. Augustine, FL.44 Francis Jr.’s siblings carried on and found careers in various industries following their brother’s death. Eduard worked as a truck driver for Florida Power and Light in 1950, while Ralph worked at a local market in St. Augustine and Lawrence worked as an electrician.45 Lawrence also served during the Vietnam War era, and perhaps found inspiration from Francis’ heroism during his own time in the military.46 In St. Augustine, where Francis spent most of his life, a memorial to the citizens of St. Johns County who gave their lives in World War II stands at the intersection of Cathedral Plaza and Charlotte Street. Francis Thomas Piet Jr.’s name remains etched on this memorial, where his legacy of military service persists.47

Originally buried in a temporary cemetery in Ulithi, in the Caroline Islands, US military personnel relocated Piet’s remains to a cemetery in Agat, Guam in 1946.48 In the years following the war, the US government helped facilitate the Return of World War II Dead Program, which allowed the families of those killed in service overseas the option to repatriate their loved ones’ remains back to the US.49 In 1948, Francis Thomas Piet Jr.’s family decided to bring him back to Florida so he could be closer to home. He now rests among his fellow Veterans in St. Augustine National Cemetery, Section D, Site 163, just half a mile away from the house on Cordova St. where he and his family lived in 1930 and just on the other side of the San Sebastian River from where his parents rest.50

Endnotes

1 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2024), entry for Francis Thomas Piet Jr.

2 “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2024), entry for Antonica Maria Reyes.

3 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2024), entry for Antonica M Piet.

4 “Florida, U.S., Naturalization Records, 1847-1995,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 14, 2024), entry for Frank Thomas Piet.

5 “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 11, 2024), entry for Frank Piet; “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 11, 2024), entry for Francis F Piet.

6 “The Dutch Touch Upon America,” GenealogyMagazine, accessed May 6, 2024, https://www.genealogymagazine.com/the-dutch-touch-upon-america/.

7 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 14, 2024), entry for Franz Piet.

8 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 11, 2024), entry for Frank Thomas Piet.

9 “Using NARA’s Index to Naturalization of World War I Soldiers,” National Archives Pieces of History: A Blog of the U.S. National Archives, accessed June 11, 2024, https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2020/11/10/using-naras-index-to-naturalizations-of-world-war-i-soldiers/.

10 “Florida, U.S., Naturalization Records, 1847-1995,” entry for Frank Thomas Piet.

11 “Antique Copying Machines,” Early Office Museum, accessed May 6, 2024, https://www.officemuseum.com/copy_machines.htm.

12 “Florida, U.S., Naturalization Records, 1847-1995,” entry for Frank Thomas Piet.

13 “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2024), entry for Francis Thomas Piet; “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,”, entry for Antonica Maria Reyes.

14 “1930 United States Federal Census,” entry for Francis Thomas Piet Jr.

15 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2024), entry for Francis Thomas Piet Jr.

16 “1930 United States Federal Census,” entry for Francis Thomas Piet Jr.; “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for Francis Thomas Piet Jr.; “The Great Depression Today,” Association for Entrepreneurship, accessed May 6, 2024, https://afeusa.org/articles/the-great-depression-and-today/.

17 By February 1943, when Francis turned eighteen, federal law required all males between eighteen and sixty five to register with Selective Service. Furthermore, in December of 1942, the military stopped accepting enlistments via volunteers. The only way to enter the service was via the draft. Based on this information, we are confident that Francis entered the US Navy during 1943, shortly after he turned eighteen years old. For more information, see “History and Records,” Selective Service System, accessed June 11, 2024, https://www.sss.gov/history-and-records/; Joshua Keeran, “US Military Relied on Draft-Induced Volunteerism,” Delaware Gazette (blog), March 11, 2021, accessed June 11, 2024, https://www.delgazette.com/2021/03/11/us-military-relied-on-draft-induced-volunteerism/.

18 “US, World War II War Diaries, 1941-1945,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed May 28, 2024), entry for Aircraft Action Report Number 72, Air Ops against Formosa, Philippines, Fr Indo-China and So Asia 1/3 - 21/45, 182-186; Allan McElhiney, “TBM/TBF Avenger Torpedo Bomber,” Naval Air Station Fort Lauderdale Museum, accessed June 21, 2024, https://www.nasflmuseum.com/the-avenger.html. During WWII, both Grumman and General Motors built the Avenger aircraft. The Grumman built aircraft used the variant designation TBF, while General Motors used TBM. In both cases, TB stood for Torpedo Bomber, while F stood for Grumman and M for General Motors.

19 “Chuck Bayless, WWII,” Emmet County, Michigan, accessed May 6, 2024, https://www.emmetcounty.org/chuck-bayless-wwii/; “Aviation Radioman,” U.S. Bureau of Naval Personnel, accessed May 6, 2024, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/ref/NAVPERS-16701/NAVPERS-16701.html#letterA.

20 “Aviation Radioman.”

21 “Chuck Bayless, WWII.”

22 “Grumman TBF-Avenger,” Wings-Aviation, accessed May 6, 2024, http://www.wings-aviation.ch/21-USNavy/Grumman-TBF/Avenger.htm.

23 “Grumman TBF-Avenger;” “Chuck Bayless, WWII.”

24 “US, World War II War Diaries, 1941-1945,” entry for Aircraft Action Report Number 72, 182-186.

25 “CVG-80,” Wings-Aviation, accessed May 6, 2024, http://www.wings-aviation.ch/24-Naval-Wings/1942/CVG-080.htm.

26 “CV 14 / CVA 14 / CVS 14 - USS Ticonderoga,” Seaforces, accessed May 6, 2024, https://www.seaforces.org/usnships/cv/CV-14-USS-Ticonderoga.htm; “Military Units,” U.S. Department of Defense, accessed May 6, 2024, https://www.defense.gov/Multimedia/Experience/Military-Units/Air-Force/#:~:text=A%20group%20consists%20of%20two,being%20part%20a%20medical%20group.

27 “CV 14 / CVA 14 / CVS 14 - USS Ticonderoga;” “CVG-80.”

28 “CV 14 / CVA 14 / CVS 14 - USS Ticonderoga;” “CVG-80.”

29 “CV 14 / CVA 14 / CVS 14 - USS Ticonderoga.”

30 “CV 14 / CVA 14 / CVS 14 - USS Ticonderoga.”

31 “When Was Taiwan Called Formosa?” Bubble Tea Island, https://bubbleteaisland.com/2023/05/10/when-was-taiwan-called-formosa/: accessed May 6, 2024.

32 “CV 14 / CVA 14 / CVS 14 - USS Ticonderoga.”

33 AP Archive, “Japanese Planes Attack USS Ticonderoga,” YouTube video, 9:52, April 13, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WGK6AT51FyY.

34 “CV 14 / CVA 14 / CVS 14 - USS Ticonderoga.”

35 “US, World War II War Diaries, 1941-1945,” entry for Aircraft Action Report Number 72, 182-186.

36 “US, World War II War Diaries, 1941-1945,” entry for Aircraft Action Report Number 72, 182-186.

37 “U.S., World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2024), entry for Francis Thomas Piet Junior.

38 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed January 20, 2024), entry for Piet, Francis Thomas Jr; “U.S., World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949,” entry for Francis Thomas Piet Junior.

39 “CV 14 / CVA 14 / CVS 14 - USS Ticonderoga.”

40 “Ticonderoga - The Big “T”,” Sound Studio Publications, accessed May 6, 2024, http://www.soundstudiopublications.com/Ticonderoga.html.

41 “USS Ticonderoga (CV/CVA/CVS-14),” National Museum of the Pacific War, accessed May 6, 2024, https://www.pacificwarmuseum.org/join-give/tributes/uss-ticonderoga-cv-14; “United States Aircraft Carrier Memorial,” Traces of War, accessed May 6, 2024, https://www.tracesofwar.com/sights/8751/United-States-Aircraft-Carrier-Memorial.htm: .

42 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2024), entry for Frank T Piet.

43 “Francis Thomas ‘Frank’ Piet Sr.,” FindaGrave, January 10, 2010, accessed June 11, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/46515120/francis_thomas_piet.

44 “Antonica Maria ‘Neca’ Reyes Piet.,” FindaGrave, January 10, 2010, accessed June 11, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/46515159/antonica-maria-piet?_gl=1*4orfyb*_gcl_au*MjUyNDQ4NDQ2LjE3MTY5MDU1ODk.*_ga*MjA4NTMzNTA0Ni4xNzE2OTA1NTkx*_ga_4QT8FMEX30*YjQwOGY4NmEtZjYwYy00YTg4LTlmMzYtMGJjMmIzY2YxYTQ0LjM3LjEuMTcxODEzNTkyMS41OS4wLjA.*_ga_LMK6K2LSJH*YjQwOGY4NmEtZjYwYy00YTg4LTlmMzYtMGJjMmIzY2YxYTQ0LjI2LjEuMTcxODEzNTkyMS4wLjAuMA..

45 “1949 St. Augustine City Directory,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2024), entry for Ralph J Piet; “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2024), entry for Eduard R Piet; “Indiana State Board of Health Certificate of Death,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 21, 2024), entry for Lawrence Piet.

46 “Indiana State Board of Health Certificate of Death.”

47 “World War II Memorial, St. Johns County. Florida,” HMdb, accessed May 6, 2024, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=143655.

48 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for Piet, Francis Thomas Jr.; Edward Steere and Thayer M. Boardman, Final Disposition of World War II Dead, 1945-51 (Washington: Historical Branch, Office of the Quartermaster General, 1957), 405.

49 “America’s World War II Burial Program,” US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration, accessed June 11, 2024, https://www.cem.va.gov/docs/wcag/history/WWII-Burial-Program-America.pdf, 18.

50 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for Piet, Francis Thomas Jr.

© 2024, University of Central Florida