Clifford E. Phillips (October 21, 1925-May 21, 1945)

3rd Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment, 6th Marine Division, US Marine Corps

By Amanda Burchins and Jim Stoddard

Early Life

Clifford Eugene Phillips served in World War II in the US Marine Corps, where he achieved the rank of Private First Class.1 Clifford was born on October 21, 1925, in Tifton, Tift County, GA, to Henry and Lucile Phillips.2 He was the third of four sons. His oldest brother, Lee Roy, was born in 1921, followed by Thurman in 1923.3 Clifford’s youngest brother, Henry Jr., was born in 1932 when Clifford was about seven years old.4

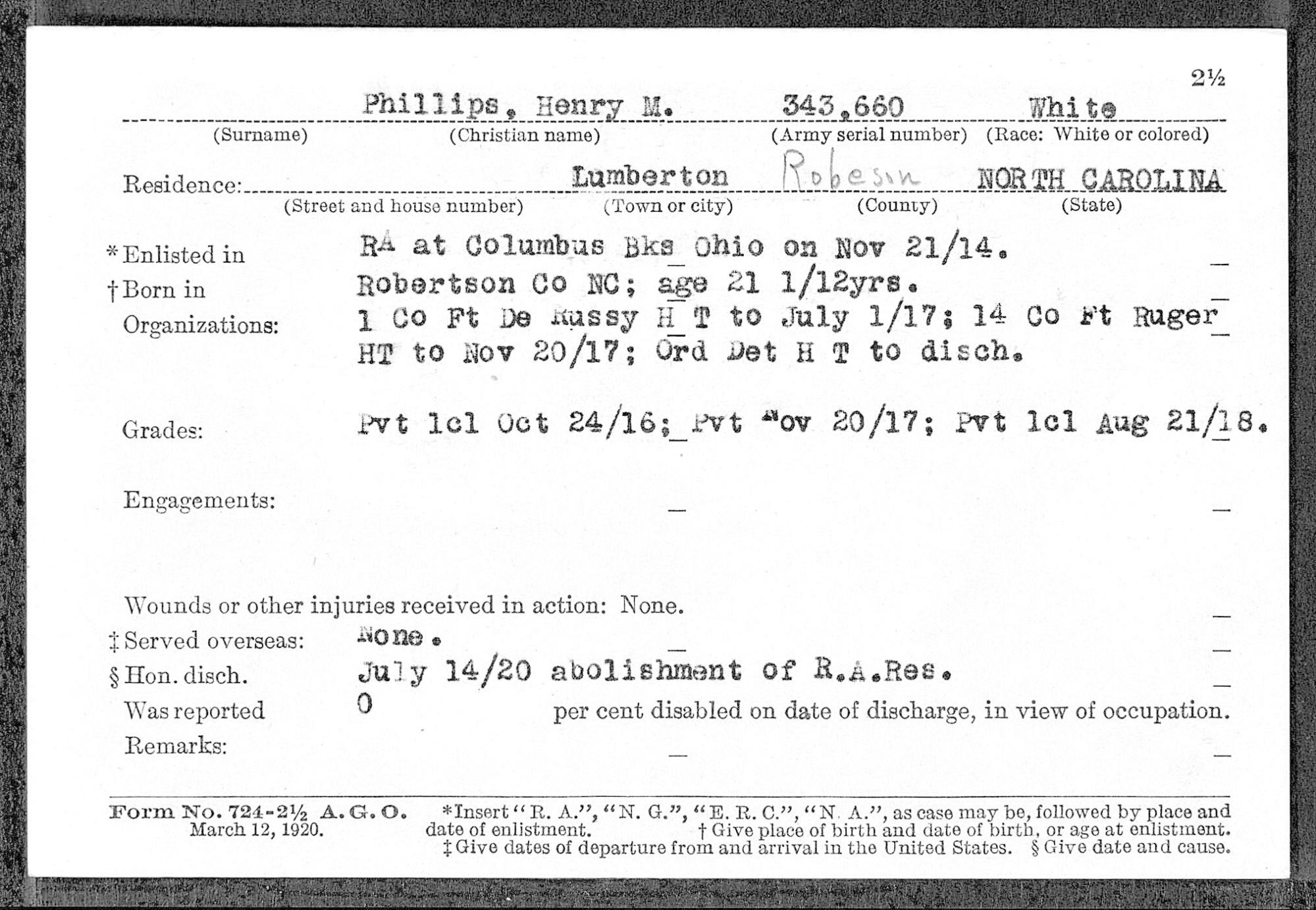

Clifford’s father Henry, a World War I Veteran, noted here, served in the US Army Reserve at Fort DeRussy and Fort Ruger, in the Territory of Hawaii, throughout the final years of the war.5 Henry married his first wife, Clara Gomes, in Honolulu, HI, on November 18, 1918, shortly after the armistice. Clara’s family originally hailed from Portugal.6 This marriage must not have lasted long, as Clara married her second husband on August 21, 1921, and Henry reported as single at the time of his military discharge on June 14, 1920.7 Following his exit from the US Army Reserve, Henry met his second wife Lucille and relocated to Georgia to start his family. He supported the family as a farm laborer in Tifton until sometime between 1930 and 1935.8 During that period, the family moved to another farm in Norman Park, GA, in neighboring Colquitt County.9 Rural farmers in Georgia began to struggle economically before the 1929 stock market crash and the official start of the Great Depression. Boll weevils entered the state in 1915 and ravaged the cotton crop through the 1920s. Georgia farmers also suffered from a three-year drought (1925-1927), which poor irrigation infrastructure exacerbated. During the Great Depression, conditions for farming families went from bad to worse. In 1930, sixty-nine percent of Georgia’s population lived in rural areas, where most were poor sharecroppers.10 Some or all of these factors likely contributed to the Phillips family’s move to Norman Park.

After his father’s hospitalization in a Veterans Administration facility, then known as the Lenwood Veterans Hospital, in Augusta, GA, sometime in the late 1930s, Clifford, his mother, and his brothers relocated to Tallahassee, FL.11 Lucile supported her family by working as a laundress, most likely at the Florida State College for Women (present-day Florida State University).12 Clifford’s oldest brother, Lee Roy, also supported the family (which, by this time, also included Lee Roy’s wife, Eloise, and infant son, Charles) as a carpenter.13 By 1943, Clifford also contributed to the family by working at the US Engineers Area Office in Tallahassee.14

Military Service

When Clifford turned eighteen years old on October 21, 1943, he registered for the draft.15 Two months later, on December 20, 1943, in Orlando, FL, Clifford enlisted in the US Marine Corps. Through January 1944, Clifford trained to become a Marine in the 5th Recruit Battalion aboard Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, SC. Unfortunately, he became ill within a day of his arrival and spent almost two weeks in the US Naval Hospital.16 Once he recovered, he completed recruit training. By April, Clifford left Parris Island and joined the Pioneer Company, Engineer Battalion at Camp Lejeune, NC’s Training Center.17 In July, he completed his training in the Engineer Battalion and moved into the Engineer Company within the Special Training Regiment of Camp LeJeune’s Training Command. Additionally, he achieved the rank of Private First Class (PFC) and became a demolition specialist on July 29.18

By this point in World War II, the Marine Corps deployed Marines from the US to the Pacific Theater in large groups called replacement drafts. On October 7, 1944, the Corps organized the 15th Replacement Draft on Camp LeJeune. Clifford became part of this draft on October 16. Once the draft filled out, it departed for Camp Pendleton, CA via rail on the 26th and arrived on the 31st.19 Over the course of the war, Camp Pendleton received and trained thousands of replacement Marines for service in the Pacific.20

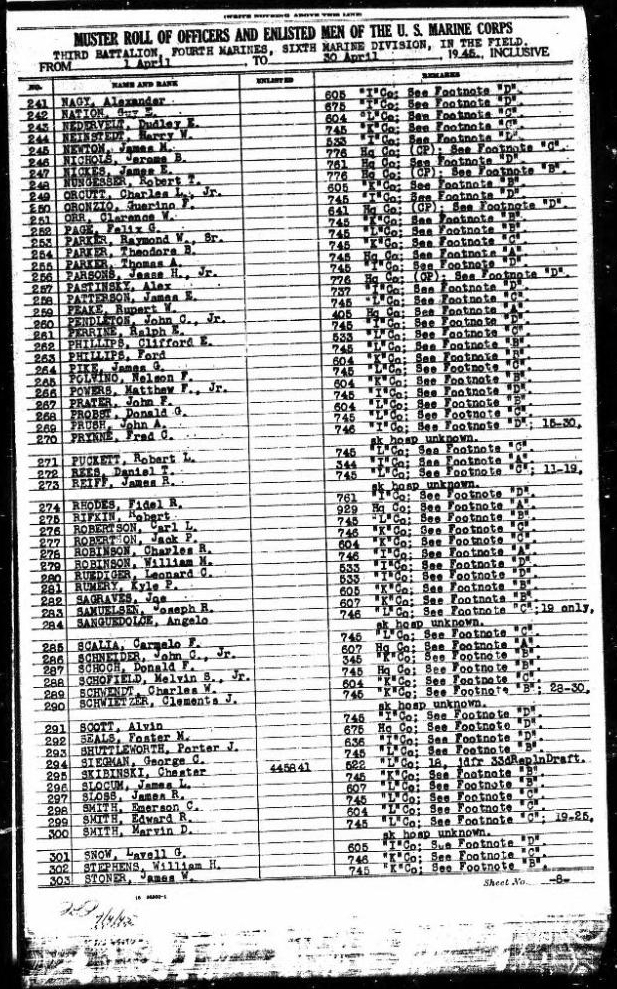

After a brief stay in Camp Pendleton, Clifford’s replacement draft departed for the Pacific Theater. By January 1945, the Marines in the 15th Replacement Draft arrived on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. On what was once a deadly battlefield earlier in the Second World War, Guadalcanal served as a formation area for the final battles of the conflict by early 1945. Clifford, and likely many from the 15th Replacement Draft, went to the 6th Marine Division (MarDiv).21 The Marine Corps had activated the 6th MarDiv on Guadalcanal in September 1944.22 It remained the only Marine Corps division formed overseas.23 Even though the 6th prepared for the invasion of Okinawa as the newest combat division, its makeup did not cast it as a “virgin” unit. The Corps formed the division around a cadre of combat-hardened Veteran Marines, then it filled out the remainder of the division with replacement drafts, such as Clifford’s cohort.24 Clifford joined 3rd Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment, 6th MarDiv.25

In March 1945, the 6th MarDiv began practicing for Operation ICEBERG, the amphibious assault of Okinawa. Clifford and the Marines of the 6th Division participated in a “dress rehearsal” for this assault between March 1-6, 1945, during which they practiced landing and combat maneuvers they planned to do once Operation ICEBERG commenced.26 On March 15, 1945, the 6th MarDiv made its way to an atoll in the Caroline Islands which served as the staging area for the Okinawa operation. The 6th MarDiv, along with the 1st and 2nd MarDivs, formed the III Amphibious Corps. This Corps served as the Marine element of the Tenth Army, formed to handle the Okinawa operation.27 The Tenth Army also included the 7th, 27th, 77th, and 96th Infantry Divisions of the US Army, which gave the Tenth Army a strength of more than 60,000 troops for the invasion of Okinawa.28

On April 1, 1945, Easter Sunday, Operation ICEBERG began. Clifford’s amphibious landing craft launched from LST #833, which made him part of the forward echelon of the assault, seen here.29 Once he and the 4th Marines hit the beaches at Hagushi (designated Red Beach 1 by the US military), they moved inland to their objective at the Yontan Airfield.30 Generally, the Japanese allowed the Americans to land unopposed on Okinawa. Instead of trying to hold the beachhead, they opted for a defense-in-depth strategy through the interior of the island.31 By April 4th, the 4th and 22nd Marines cut the island in half, just below its midway point, “at a line between the village named Ishicha and westward to Naka Domari.” The following day, Clifford’s regiment moved northeast along Okinawa’s Pacific Coast and achieved its Day 15 objective by Day 5 of the battle. This fast pace allowed III Amphibious Corps to move up 6th MarDiv’s objectives and send the division further north. The 4th Marines faced little resistance along its fifty-mile drive north and reached Hedo Misaki on the northern end of the island by April 8.32

The next major objective for the 6th MarDiv was to take the Motobu Peninsula. The peninsula jutted off the western coast of Okinawa, and intelligence reports indicated about 3000 Japanese troops held Motobu.33 Initially, III Amphibious Corps charged the 6th MarDiv’s 29th Marines to take Motobu and placed the 4th Marines in reserve at the base of the peninsula.34 Once the reconnaissance units of the 29th Marines determined where the Japanese concentrated the majority of their forces on April 14, the 4th Marines joined with the 29th Marines to take the peninsula. The battle lasted four days. The battalions of the 6th MarDiv attacked the Japanese from three sides. On April 20, they secured “all of Okinawa north of the original landing beaches.”35

While 6th MarDiv secured the northern area of Okinawa, the majority of divisions in the Tenth Army fought to secure the south. Sharp ridges and deep ravines made up the narrow southern portion of the island. In this terrain, the Japanese concentrated their main defense of Okinawa.36 Between May 3-7, the division marched thirty-four miles through heavy rains from the Motobu Peninsula to the southern city of Chibana.37 The 6th MarDiv, with the 4th Marines at its center, formed up on the western end of the Tenth Army’s line as it assaulted Okinawa’s southern defenses.38 The divisions' regiments probed the Japanese defenses in an attempt to outflank the fortified Shuri Line. While the 6th MarDiv could not find a flanking path, it did locate the three key terrain features of Horseshoe Ridge, Sugar Loaf Hill, and Half Moon Hill, which each anchored the western complex of the Japanese defense.39 The 6th MarDiv began its attack on the western complex on May 12. Over the next week, the 22nd and 29th Marines assaulted the high ground, gained territory yards at a time, and, by the 19th, encircled Sugar Loaf and Half Moon Hills.40

While under fire here, Clifford’s 4th Marine Regiment relieved the 29th Marines. On the morning of the 20th, the 4th Marines attacked and seized a portion of Horseshoe Ridge. That night, the Japanese counterattacked, concentrating on Clifford’s 3rd Battalion.Third Battalion held the line through the night and inflicted 300 casualties on the Japanese. The battalion suffered nineteen wounded and one Marine killed. Sadly, Clifford Eugene Phillips accounted for the one Marine lost.41 Killed in action on May 21, 1945, Clifford was just five months shy of his twentieth birthday. His fellow Marines buried him at the 6th Marine Division Cemetery #1 on Ryukyu-Retto, Okinawa Shima.42

Legacy

Following Clifford’s death, the 6th MarDiv continued fighting on Okinawa. On June 1, 1945, it finally captured Okinawa’s capital, Naha, and continued the larger Okinawa operation until June 21, when its “zone of action ceased.” The 6th MarDiv received credit for capturing two-thirds of Okinawa. The division took 3,500 Japanese soldiers as prisoners and killed 23,000 during the battle for the island.43 During the first week of July 1945, it held a dedication ceremony for the 6th Marine Division Cemetery before departing for Guam. In October 1945, the 6th MarDiv deployed to Tsingtao, China, with a mission to assist the local authorities in humanitarian efforts; care for and release of allied prisoners of war, which the US military designated as “Recovered Allied Military personnel;” and accept the local surrender of Japanese forces. After participating exclusively in the Battle of Okinawa, the Marine Corps officially deactivated the 6th Marine Division on April 1, 1946.44

In the decades after Cliford’s death, the Phillips family contended with more tragedy. Clifford’s father, Henry, died on November 2, 1955 in Tift County, GA.45 On the morning of December 8, 1964, Clifford’s older brother, Thurman, was killed when his tractor-trailer overturned near Cottonwood, AL.46 On March 24, 1990, Clifford’s oldest brother Lee Roy died in Cowarts, AL.47 Clifford’s mother, Lucile, outlived all but the youngest of her four sons, Henry Jr. After the war, she and Henry Jr. moved to Cottonwood, AL, and lived with her sister, Lila, and brother-in-law, Marshall Davis.48 Lucile died on August 12, 1996, in Bonifay, FL, at the age of ninety-three.49 Henry Jr. died on December 8, 1998.50

When Clifford filled out his draft registration card in 1943, he named his mother, Lucile, as his next of kin. After the war, the US government contacted her about the Veterans Administration’s “Return of the Dead Program.” This program gave families the choice to either leave their loved one’s remains in a permanent overseas cemetery maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) or have them returned home.51 She chose to have Clifford’s remains returned to the US from the Okinawa 6th Marine Division Cemetery on Ryukyu-Retto, Okinawa Shima. They were reinterred in Florida on April 14, 1949. Clifford Eugene Phillips now rests among his fellow Veterans in the St. Augustine National Cemetery in Section D, site 177.52

Endnotes

1 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed January 20, 2024), entry for Clifford Eugene Phillips.

2 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for Clifford Eugene Phillips; “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed February 13, 2023), entry for Henry M. Phillips, District 0009, Tifton, Tift, Georgia.

3 “1930 United States Federal Census,” entry for Henry M. Phillips.

4 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed February 13, 2024), entry for Clifford Eugene Phillips, Tallahassee, Leon, Florida.

5 “North Carolina, World War I Service Cards, 1917-1919,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 9, 2024), entry for Henry M. Phillips.

6 “Hawaii, U.S. Marriage Certificates and Indexes, 1841-1944,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 14, 2024), entry for Henry M. Phillips.

7 “Leon. Deeds, Military Records,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org: accessed May 14, 2024), entry for Henry M. Phillips; “Hawaii, U.S. Marriage Certificates and Indexes, 1841-1944,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 14, 2024), entry for Clars Clara Phillips.

8 “1930 United States Federal Census,” entry for Henry M. Phillips; “North Carolina, World War I Service Cards, 1917-1919,” entry for Henry M. Phillips.

9 “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for Clifford Eugene Phillips, Tallahassee, Leon, Florida.

10 Jamil Zainaldin, “Great Depression,” in New Georgia Encyclopedia, September 29, 2020, accessed April 27, 2024, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/great-depression/.

11 “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for Clifford Eugene Phillips; “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed February 13, 2024), entry for Henry M. Phillips, ED 121-62, Augusta, Richmond, Georgia; “Historic American Buildings Survey: US Veterans Hospital No. 62, Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center (Lenwood Veterans Hospital, Lenwood Hotel, Mount St. Joseph Academy,” National Park Service and US Department of the Interior, accessed May 16, 2024, http://lcweb2.loc.gov/master/pnp/habshaer/ga/ga1000/ga1054/data/ga1054data.pdf. By the 1940s, the Lenwood Veterans Hospital in Augusta, GA functioned mainly as a treatment facility for neuro-psychiatric patients. Although the hospital offered additional health services, the fact that Henry Sr. received inpatient care at this facility suggests he may have received this kind of treatment.

12 “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for Clifford Eugene Phillips; “History,” Florida State University, accessed April 18, 2024, https://www.fsu.edu/about/history.html.

13 “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for Clifford Eugene Phillips.

14 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed February 12, 2024), entry for Clifford E Phillips, Florida.

15 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” entry for Clifford E Phillips.

16 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 22, 2024), entry for Clifford E Phillips, January 1944.

17 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 22, 2024), entry for Clifford E Phillips, April 1944.

18 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 22, 2024), entry for Clifford E Phillips, July 1944.

19 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 22, 2024), entry for Clifford E Phillips, October 1944.

20 “History of Camp Pendleton,” Oceanside Chamber of Commerce, n.d., https://www.oceansidechamber.com/oceanside-blog/history-of-camp-pendleton.

21 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 22, 2024), entry for Clifford E Phillips, January 1945.

22 Bevan G. Cass and Kenneth J. Long, “A Chronology of the 6th Marine Division on Okinawa Shima-1945,” in Okinawa 1945 Vol. 1 (1993), 110.

23 Alexander, Joseph H. The Final Campaign: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa. Washington, D.C., Marine Corps Historical Center, 1996, 5.

24 "The Invasion of Okinawa: A Little Hill Called Sugar Loaf," The National WWII Museum New Orleans, last modified May 11, 2020, accessed April 19, 2024. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/okinawa-invasion-sugar-loaf-hill.

25 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958,” entry for Clifford E Phillips, January 1945; Cass and Long, “A Chronology of the 6th Marine Division on Okinawa Shima-1945,” 110. To form the 4th Marine Regiment, the Marine Corps redesignated the four Marine Raider Battalions which, ironically, helped to secure Guadalcanal in the 1942/43 campaign.

26 James R Stockman, The Sixth Marine Division, Historical Division Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1946, 4.

27 Stockman, The Sixth Marine Division, 5.

28 “Battle of Okinawa: The National WWII Museum: New Orleans,” The National WWII Museum New Orleans, accessed April 18, 2024. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/topics/battle-of-okinawa; “Iwo Jima and Okinawa: Death at Japan’s Doorstep,” The National WWII Museum New Orleans, accessed April 18, 2024, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/iwo-jima-and-okinawa-death-japans-doorstep#:~:text=The%20Battle%20of%20Okinawa,anticipated%20invasion%20of%20mainland%20Japan.

29 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 22, 2024), entry for Clifford E Phillips, April 1945. The forward echelon makes up the initial wave of troops in an amphibious assault.

30 Cass and Long, “A Chronology of the 6th Marine Division on Okinawa Shima-1945,” 110; Alexander, The Final Campaign, 13 & 14.

31 Alexander, The Final Campaign, 13.

32 Cass and Long, “A Chronology of the 6th Marine Division on Okinawa Shima-1945,” 111.

33 Stockman, The Sixth Marine Division, 6.

34 Cass and Long, “A Chronology of the 6th Marine Division on Okinawa Shima-1945,” 111.

35 Stockman, The Sixth Marine Division, 7.

36 Stockman, The Sixth Marine Division, 8.

37 Cass and Long, “A Chronology of the 6th Marine Division on Okinawa Shima-1945,” 113.

38 Alexander, The Final Campaign, 38.

39 Stockman, The Sixth Marine Division, 9; “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for Clifford Eugene Phillips.

40 Cass and Long, “A Chronology of the 6th Marine Division on Okinawa Shima-1945,” 114-116.

41 Stockman, The Sixth Marine Division, 12.

42 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms,” Ancestry, Clifford Eugene Phillips.

43 Stockman, The Sixth Marine Division, 16.

44 Stockman, The Sixth Marine Division, 18 and 19.

45Find a Grave, database, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/55661024/henry_m-phillips: accessed February 12, 2024), memorial page for Henry M Phillips (5 Oct 1892-2 Nov 1955), Find a Grave Memorial ID 55661024, citing Turner Primitive Baptist Church Cemetery, Ferry Lake, Tift County, Georgia, USA; Maintained by “SearcherToo” (contributor 51052476).

46 “Truck Overturns, Driver Is Killed Near Cottonwood,” The Dothan Eagle (Dothan, AL), December 8, 1964, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-dothan-eagle-truck-overturns-drive/140934275/.

47 “Obituary: Lee Roy Phillips,” The Dothan Progress (Dothan, AL), March 28, 1990, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-dothan-progress-lee-roy-phillips-obi/140939732/.

48 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 15, 2024), entry for Lucile Phillips, Cottonwood, Houston, Alabama.

49 “Obituary: Lucile Silas Phillips,” The Dothan Eagle (Dothan, AL), August 13, 1996, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-dothan-eagle/146258415/.

50Find a Grave, database, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/100242143/henry_m-phillips: accessed February 12, 2024), memorial page for Henry M. Phillips Jr. (26 Oct 1932-8 Dec 1998), Find a Grave Memorial ID 100242143, citing Crestlawn Cemetery, Avon, Houston County, Alabama, USA; Maintained by “Green” (contributor 46605915).

51 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, America’s World War II Burial Program, 2020, https://www.cem.va.gov/docs/wcag/history/WWII-Burial-Program-America.pdf.

52 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for Clifford Eugene Phillips.

© 2024, University of Central Florida