Curtis Bernard Beville (July 30, 1919-May 31, 1944)

Company F, 179th Infantry Regiment, 45th Infantry Division, US Army

By John Barton and Oliver Brown

Early Life

Curtis Bernard Beville was born in Center Hill, Sumter County, FL on July 30, 1919, on his parents' first wedding anniversary.1 Curtis’s father, John Beville, was born September 27, 1887, and his mother, Lena Currington, on September 29, 1896.2 Curtis was the first of three children, and his parents’ only son. He had two younger sisters, Marjorie (1924) and Viola (1926).3

John’s ancestors had lived in North America since before the American Revolution. His great-great-grandfather, Robert Beville, served as a Private in the Georgia Line, a formation of infantry regiments from Georgia that constituted part of the Continental Army.4 The Beville family remained in Georgia throughout the first half of the nineteenth century and settled in central Florida sometime before 1860.5 This relocation mid-century may have owed to the recently-fought Seminole Wars. The Seminole Wars, three violent conflicts fought between the US military and Seminole Tribes in Florida between the 1810s and 1850s, resulted in the forced removal of thousands of Seminoles to territory west of the Mississippi River. Some Seminole warriors continued to resist, going deeper into the Everglades. The removal of so many Seminoles facilitated white control and opened more of the peninsula to white agricultural settlement. Along with farming came the expansion of slavery.6 The Bevilles owned enslaved people during this period, and by the Civil War had accumulated significant wealth.7 In 1860, Granville Beville, John’s grandfather, owned thirty-one enslaved people, all of whom contributed to his personal estate valued at more than $18,000 at the time ($700,000 in today’s currency).8

In 1870, following the abolition of slavery, Granville Beville’s personal estate value dropped to $4,000, though the family maintained local political influence in the area.9 Thomas Beville, John’s father, served as a county commissioner for Sumter County, FL in the early twentieth century.10 During this time, however, tragedy struck the family. Before his marriage to Curtis’ mother Lena, John had been married once before to Margaret Harder, the daughter of German immigrants Bruno and Frances Harder.11 John and Margaret married on March 1, 1908.12 A year later, in 1909, John murdered Margaret’s parents following a domestic dispute.13 According to contemporary newspaper reports, Margaret’s parents did not approve of their daughter’s marriage to John and tried to convince her to leave her husband. In early September 1909, while Margaret stayed with her parents at their home in Sumterville, FL, John traveled to the Harder home and demanded Margaret return with him. An argument ensued, and John shot the couple, killing them both while Margaret remained in the home.14 Criminally tried for each murder separately in 1910, a jury acquitted John for the killing of Bruno Harder, agreeing with his claim of self-defense, but found him guilty of third-degree murder for the killing of Frances Harder. Judge W.S. Bullock sentenced John to ten years in prison.15 Although a witness to the killings, Margaret refused to testify against her husband in court, for which she spent a month in jail for contempt.16 John appealed his conviction, and in June 1911, just one year after his sentencing, the Florida Supreme Court overturned the ruling on the grounds of jury mismanagement.17 John Beville became a free man. By 1917, John and Margaret had divorced.18

On June 5, 1917, two months after the US officially entered the First World War, John Beville registered for the draft, though he never served.19 By 1920, the newly married Beville family had an infant son and lived on a farm they owned. John worked as a truck farmer– someone who lives near a town and farms exclusively to sell to the people in town. Lena took care of the home, her three children, and worked hard on their family farm.20 Following prosperity in the early years of their marriage, the Great Depression, which began after the stock market collapsed in October 1929, greatly affected the Beville family. Though they owned their own farm in 1920, they rented a home on Venable St. in Center Hill, FL by 1930.21 John worked as a fruit and vegetable packer to support his family.22 On March 20, 1931, in the midst of the Depression, John passed away from a heart attack following a brief illness at the age of forty-three.23 Six years later, on November 14, 1937, Curtis’s mother Lena remarried to H.N. Redding, a farmer from Sumter County, FL.24

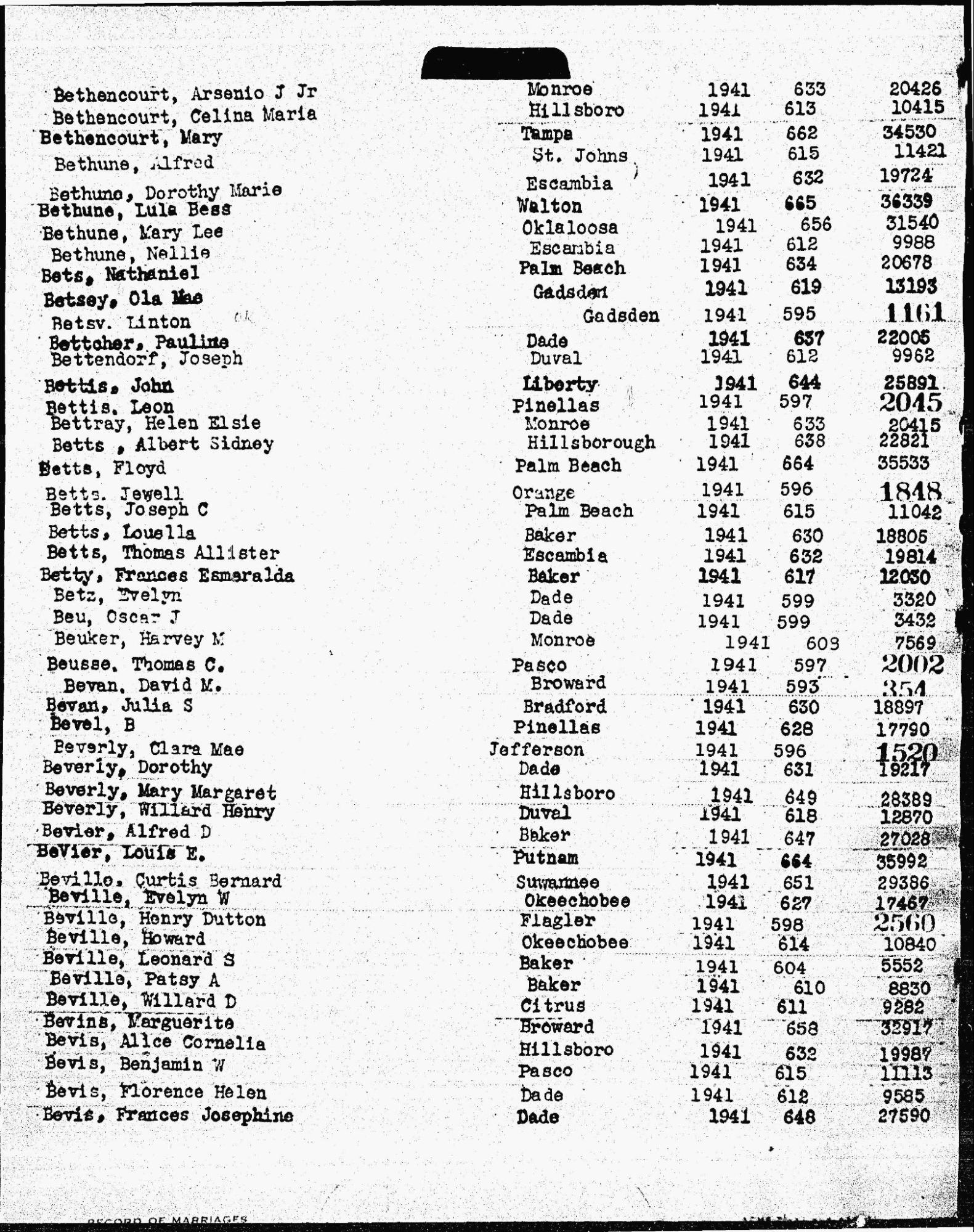

Curtis completed at least two years of high school by 1940, an accomplishment for a student during the Great Depression.25 By the time he turned twenty-one, Curtis had gotten a job working for the Seaboard Air Line Railway, an important railway that ran throughout the southeastern US in the first half of the twentieth century.26 On September 16, 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Selective Training and Service Act into law, which instituted the first peacetime draft in US history.27 Curtis registered for the draft in Bushnell, FL on October 16, 1940.28 Around this time, Curtis met Dorothy Mildred Landen, a stenographer from Suwannee County, FL, and applied for a marriage license on September 6, 1941.29 Exactly one month later, on October 6, Reverend J.M. Smiley married the couple in Live Oak, FL, as indicated in the marriage record here.30

Military Service

Shortly after Curtis and Dorothy married, Curtis entered the US Army. Curtis enlisted at Camp Blanding in Starke, FL on October 17, 1941.31 During Curtis’ first few months in the Army, Japan attacked the US at Pearl Harbor. A day after this attack, on December 8, 1941, the US officially entered World War II. Over the next two years, Curtis continued to train as the Army grew to face a two-front war. In December 1943, Curtis traveled home to visit his family before deploying overseas. Two months later, in February 1944, Curtis left the US for the European Theater as part of the 45th Infantry Division (ID), nicknamed the “Thunderbirds.”32 Curtis joined Company F, 179th Infantry Regiment, 45th ID. As part of the 5th US Army, the 45th ID sailed from Virginia to North Africa in June 1943 to prepare for the invasion of Sicily and the Italian Peninsula.33

In July 1943, the Allies first penetrated Western Europe through Italy via an Allied amphibious landing on Sicily. While the Allies took the island relatively quickly, progress up the boot of Italy slowed in the early months of 1944. The Allies bashed against the German Army’s heavily fortified Gustav Line, which stretched across the Italian peninsula and barred movement toward Rome.34 To reach Rome, the Allies sought a way around the Gustav Line. On January 22, the Allies landed troops at Anzio, a beachhead on the west coast of Italy eighty miles behind the Gustav Line with direct access to Rome. The Allies fought violently to hold and break out of the Anzio beachhead for the next five months.35

These conditions persisted when Curtis and his fellow replacements arrived in Italy in early 1944.36 During a period of heavy fighting at Anzio from February 12-19, 1944, the 179th Infantry Regiment lost over half of its men and officers as casualties.37 Curtis and his comrades in the 179th faced brutal conditions along the front, including entrenched foxhole fighting. As the Allies fought to break out of Anzio, the 179th Infantry rotated its battalions frequently, sending men to the front for eight days and allowing them four days of rest in the rear. Replacements, both battle-hardened soldiers and new recruits, continued to arrive throughout the late winter and spring of 1944.38

On May 7, the Army initiated a full-scale offensive to end the stalemate after four months of fighting. Commanding officers tasked the 179th Infantry Regiment with holding their position against an expected German counter-attack after the Allied offensive started. On May 26, after the German lines began to crumble, Curtis and the 179th joined the general Allied advance. The leading elements of the 179th sustained heavy casualties on May 28 as they faced German opposition. Through intense fighting, the 179th managed to overwhelm the Germans and enveloped their positions. Curtis and his comrades in Company F, located in the lead battalion, faced strong resistance but captured the village of Colle Cavalieri in late May. The Germans threw everything they had at the 179th, but could not stop the advance. On May 31, the Germans launched a final counterattack against the entrenched 179th, deploying artillery and mortar fire.39 Though the 179th’s defenses held, during this bloody fighting fragments from an artillery shell wounded Curtis in the leg.40 Curtis Bernard Beville succumbed to his injuries and died on May 31, 1944, at just twenty-four years old.41

Legacy

Curtis’ comrades initially interred him with his fellow fallen soldiers in the Nettuno Cemetery, Italy, just south of Rome (what became the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery).42 His unit continued to fight back against the Axis forces until the Germans retreated in early June, 1944. The 179th Infantry Regiment and the rest of the “Thunderbirds” then traveled across the Tiber River to Rome to aid in the liberation of the city. After arriving in North Africa in June 1943, the regiment had 236 days of action in Italy and 129 days of rest. With Rome liberated from Axis control, the 45th ID trained for the massive amphibious landing in southern France, codenamed Operation Dragoon. The 179th Infantry landed on La Nartelle beach, about eighty miles east of Marseille, France in August 1944.43 Once out of the south of France, it went on to take part in the Ardennes and Rhineland Campaigns.44 When Germany surrendered to the Allies in May 1945, the “Thunderbirds,” began their preparations to join the Pacific Theater, though the war ended on September 2, 1945, before they could redeploy.45

The War Department informed Curtis’ mother, Lena, of her son’s death in June 1944.46 Curtis posthumously earned the Bronze Star, awarded “for heroism in action against the enemy which cost him his life.” Dorothy, Curtis’ widow, received the medal through the mail at her residence in the Florida state capital of Tallahassee. The announcement appeared in the paper on July 30, 1944, which would have been Curtis’ twenty-fifth birthday.47 Just like his fellow soldiers, Curtis remains lauded for his service to his country and the ultimate sacrifice he made to the Allied cause. Following the war, the US government instituted the Return of World War II Dead Program. This program allowed the families of Veterans killed overseas to repatriate their loved one’s remains to the US, if they wished, so they could rest closer to home.48 In 1948, Curtis’ widow, Dorothy, as his next of kin, decided to bring her husband back to Florida. Curtis Bernard Beville now rests among his fellow Veterans in St. Augustine National Cemetery, Section D, Plot 178.49

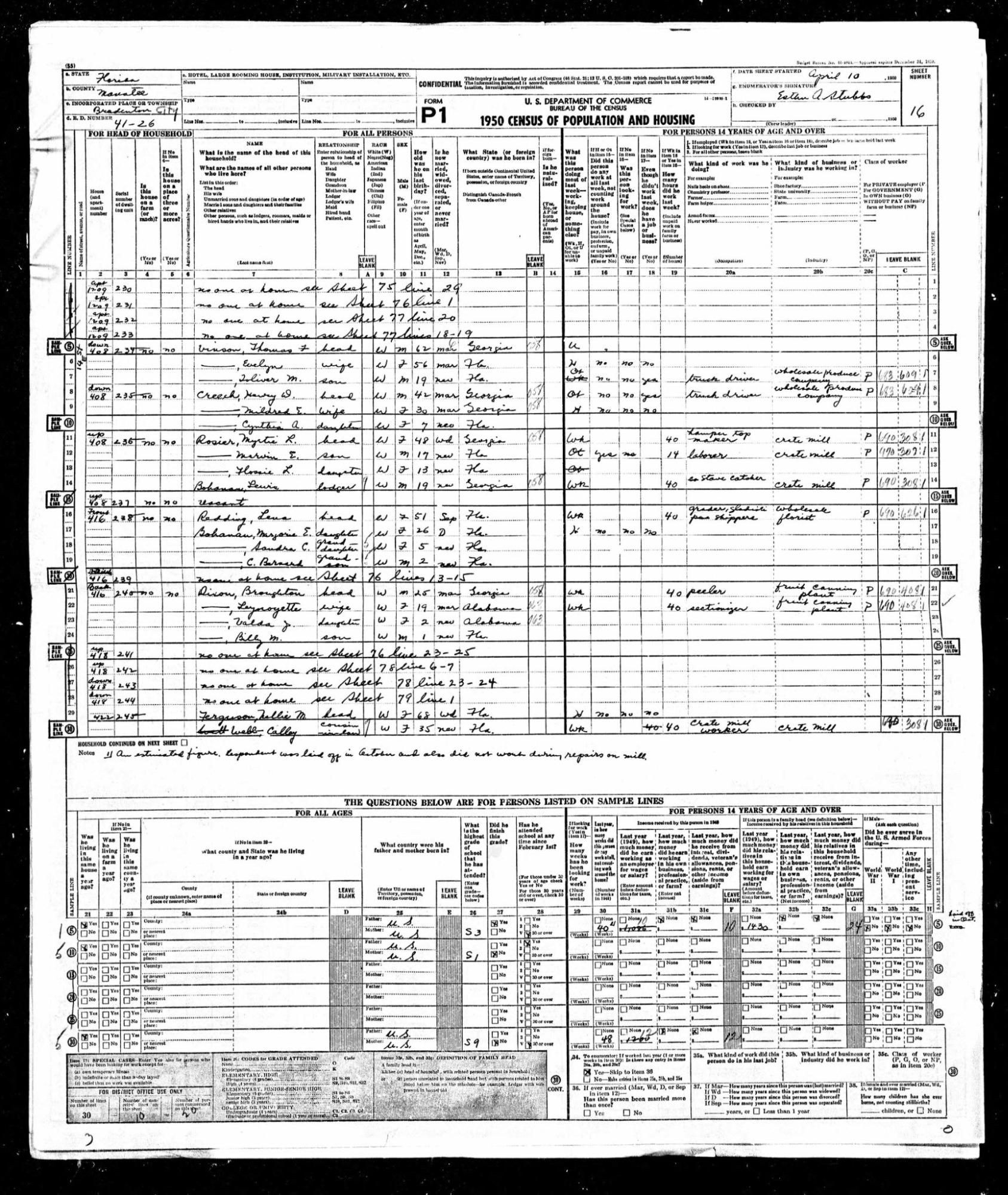

In November 1945, Curtis’ sister Betty married a Veteran, Asa Varner, in his home state of Alabama.50 Curtis’ other sister, Marjorie, married Sandford Bohanan, a farmer from Jacksonville, in April 1943.51 They had a daughter, Sandra, born in 1944, and in 1948 had a son whom they named Curtis Bernard, after Marjorie’s beloved brother, as noted on the 1950 US Federal Census. By 1950, Marjorie had separated from her husband and lived with her mother, Lena, and her two children in Bradenton, FL.52 In the years after the war, Curtis’ widow, Dorothy, remarried to Reid C. Poindexter, a Florida Highway Patrol officer, and in 1950 lived with him in Leon County, FL.53 Reid died in 1973, at the age of sixty-five.54 Nine years later, on Christmas Day 1982, Dorothy, twice widowed, passed away at the age of sixty.55 Just a few years later, on December 18, 1984, Curtis’ mother passed away at the age of eighty-eight, leaving behind her two daughters, four grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren.56 Curtis’ memory continues to live on through the legacies of the people he left behind. His sisters, mother, Army comrades, and his nephew, named for him, all play a part in making sure that the memory of Curtis and his heroic actions never fade away.

Endnotes

1 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards, 1940,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Curtis Beville, Sumter County, FL; “Florida, U.S. County Marriage Records 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for John Beville, Sumter County, FL.

2 “John Smith Beville,” FindAGrave, May 24, 2009, accessed June 24, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/37439125/john-smith-beville?_gl=1*po620s*_gcl_au*MjUyNDQ4NDQ2LjE3MTY5MDU1ODk.*_ga*MjA4NTMzNTA0Ni4xNzE2OTA1NTkx*_ga_4QT8FMEX30*YjQwOGY4NmEtZjYwYy00YTg4LTlmMzYtMGJjMmIzY2YxYTQ0LjUwLjEuMTcxOTI0MzU4MC41OS4wLjA.*_ga_LMK6K2LSJH*YjQwOGY4NmEtZjYwYy00YTg4LTlmMzYtMGJjMmIzY2YxYTQ0LjM5LjEuMTcxOTI0MzU4MC4wLjAuMA..; “Lena Currington Beville,” FindAGrave, May 24, 2009, accessed June 24, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/37439124/lena_curington_beville.

3 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Curtis Beville, Sumter County, FL.

4 Amy Cresswell Dunne, Lineage Book: National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, Volume CXL (Washington: National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, 1934), 177.

5 “1860 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Granvill Beville, Sumter County, FL.

6 “Plantation Culture: Land and Labor in Florida History,” Florida Memory, accessed June 23, 2024, https://www.floridamemory.com/learn/exhibits/photo_exhibits/plantations/plantations3.php.

7 “1820 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Granvil Bevill, Screven County, GA; “1850 U.S. Federal Census–Slave Schedules,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 23, 2024), entry for Granville Beville, Lowndes County, GA; “1860 U.S. Federal Census–Slave Schedules,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 23, 2024), entry for Granville Beville, Sumter County, FL; Granville Beville owned twelve enslaved people in 1820, while his son, also named Granville Beville, owned twenty-eight in 1850, and thirty-one in 1860.

8 “1860 U.S. Federal Census–Slave Schedules,” entry for Granville Beville; “1860 United States Federal Census,” entry for Granvill Beville.

9 “1870 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Granville Bevill, Sumter County, FL.

10 “Shooting in Sumter County,” Ocala Evening Star, September 7, 1909, 2.

11 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Margarette Harder, Sumter County, FL; Bruno and Frances arrived in the US in 1884, six years before their daughter Margaret’s birth.

12 “Florida, U.S. County Marriage Records 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Margaret Harder, Sumter County, FL.

13 “Victims of Dual Tragedy Laid to Rest in Sumter,” Tampa Tribune, September 8, 1909, 1.

14 “Sumter County’s Tragedy,” Ocala Evening Star, September 9, 1909, 1.

15 “He Killed Two; Gets Ten Years,” Weekly Tribune (Tampa, FL), April 28, 1910, 8.

16 “Mrs. Beville in Contempt,” Miami News, November 15, 1909, 2.

17 Beville v. State, 55 So. 854,61 Fla. 8, https://case-law.vlex.com/vid/beville-v-state-888179580.

18 “U.S. World War I Draft Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com, accessed May 15, 2024), entry for John Beville, Sumter, Florida.

19 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for John Beville, Sumter County, FL; “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for John Beville, Sumter County, FL.

20 “1920 United States Federal Census,” entry for Curtis Beville.

21 “1920 United States Federal Census,” entry for Curtis Beville; “1930 United States Federal Census,” entry for Curtis Beville.

22 “1930 United States Federal Census,” entry for Curtis Beville.

23 “Florida Deaths, 1877-1939,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org: accessed June 24, 2024), entry for John Beville, Sumter County, FL

24 “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for H N Redding, Sumter County, FL; “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Curtis Beville, Center Hill, FL.

25 “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for Curtis Beville, Sumter County, FL.

26 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards, 1940,”entry for Curtis Beville; Abraham Parish, “Transporting Literacy, Prosperity, and the American Dream: The Seaboard Air Line Railway at the Turn of the 20th Century,” Library of Congress Blogs, accessed June 24, 2024, https://blogs.loc.gov/maps/2023/10/transporting-literacy-prosperity-and-the-american-dream-the-seaboard-air-line-railway-at-the-turn-of-the-20th-century/.

27 “Research Starters: The Draft and World War II,” The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, accessed June 24, 2024, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/students-teachers/student-resources/research-starters/draft-and-wwii.

28 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards, 1940,”entry for Curtis Beville.

29 “1941 Application for Marriage,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com, accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Curtis Beville, Sumter County, FL.

30 “1941 Marriage License,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com, accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Curtis Beville, Sumter, Florida.

31 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com, accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Curtis Beville, Camp Blanding, FL.

32 “Son of Manatee Resident Killed on the Italian Front,” Bradenton Herald, July 7, 1944; Department of Military Affairs. St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide: Preliminary Abridged Edition. St. Augustine, FL: St. Francis Barracks Special Archives, 1989, 225, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00047708/00001/images/225.

33 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide, 225; Warren P. Munsell, The Story of a Regiment, a History of the 179th Regimental Combat Team (New York: Warren P. Munsell, 1946), 22-28.

34 “The Gustav Line: Italy Divided in Two between the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian Seas,” Liberation Route Europe, accessed June 24, 2024, https://www.liberationroute.com/themed-routes/62/the-gustav-line-italy-divided-in-two-between-the-adriatic-and-tyrrhenian-seas.

35 “The Allied Campaign in Italy, 1943-45: A Timeline, Part Two,” The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, May 25, 2022, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/allied-campaign-italy-1943-45-timeline-part-two.

36 Department of Military Affairs. St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide: Preliminary Abridged Edition. St. Augustine, FL: St. Francis Barracks Special Archives, 1989, 225, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00047708/00001/images/225.

37 Munsell, Warren P., "The story of a regiment, a history of the 179th Regimental Combat" (1946). World War Regimental Histories. 34. http://digicom.bpl.lib.me.us/ww_reg_his/34

38 Warren P. Munsell, The Story of a Regiment, a History of the 179th Regimental Combat Team (New York: Warren P. Munsell, 1946), 34.

39 Munsell, The Story of a Regiment, a History of the 179th Regimental Combat, 34.

40 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide, 225.

41 “U.S., World War II Hospital Admission Card Filed, 1942-1954,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 24, 2024), entry for Curtis B Beville.

42 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1948,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 13, 2024), entry for Curtis Beville; “Sicily-Rome American Cemetery,”American Battle Monuments Commission, (accessed July 1, 2024: https://www.abmc.gov/Sicily-Rome).

43 Munsell, The Story of a Regiment, a History of the 179th Regimental Combat, 71.

44 Munsell, The Story of a Regiment, a History of the 179th Regimental Combat, 96.

45 Munsell, The Story of a Regiment, a History of the 179th Regimental Combat, 131.

46 “Son of Manatee Resident Killed on the Italian front,” July 7, 1944.

47 “Bronze Star,” Bradenton Herald, July 30, 1944, 2.

48 “America’s World War II Burial Program,” US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration, accessed May 31, 2024, https://www.cem.va.gov/docs/wcag/history/WWII-Burial-Program-America.pdf, 4-5.

49 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 13, 2024), entry for Curtis Beville.

50 “Alabama, U.S. Marriage Index, 1800-1969,” database Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Betty Beville, Autauga County, AL.

51 “Florida, U.S. County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Marjorie Eileen Beville, Polk County, FL; “U.S., World War II Draft Cards, 1940,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Sandford Sisson Bohanan, Polk County, FL.

52 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Marjorie Beville, Manatee County, FL.

53 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 16, 2024), entry for Dorothy Poindexter, Leon County, FL.

54 “Deaths,” Tallahassee Democrat, August 22, 1973, 12.

55 “Mildred Beville Poindexter” Tallahassee Democrat, December 24, 1982.

56 “Lena Beville Redding,” Orlando Sentinel, December 20, 1984, 6.

© 2024, University of Central Florida