Crozier Williams (March 1, 1895–October 15, 1948)

By Sara Nazarian

Early Life

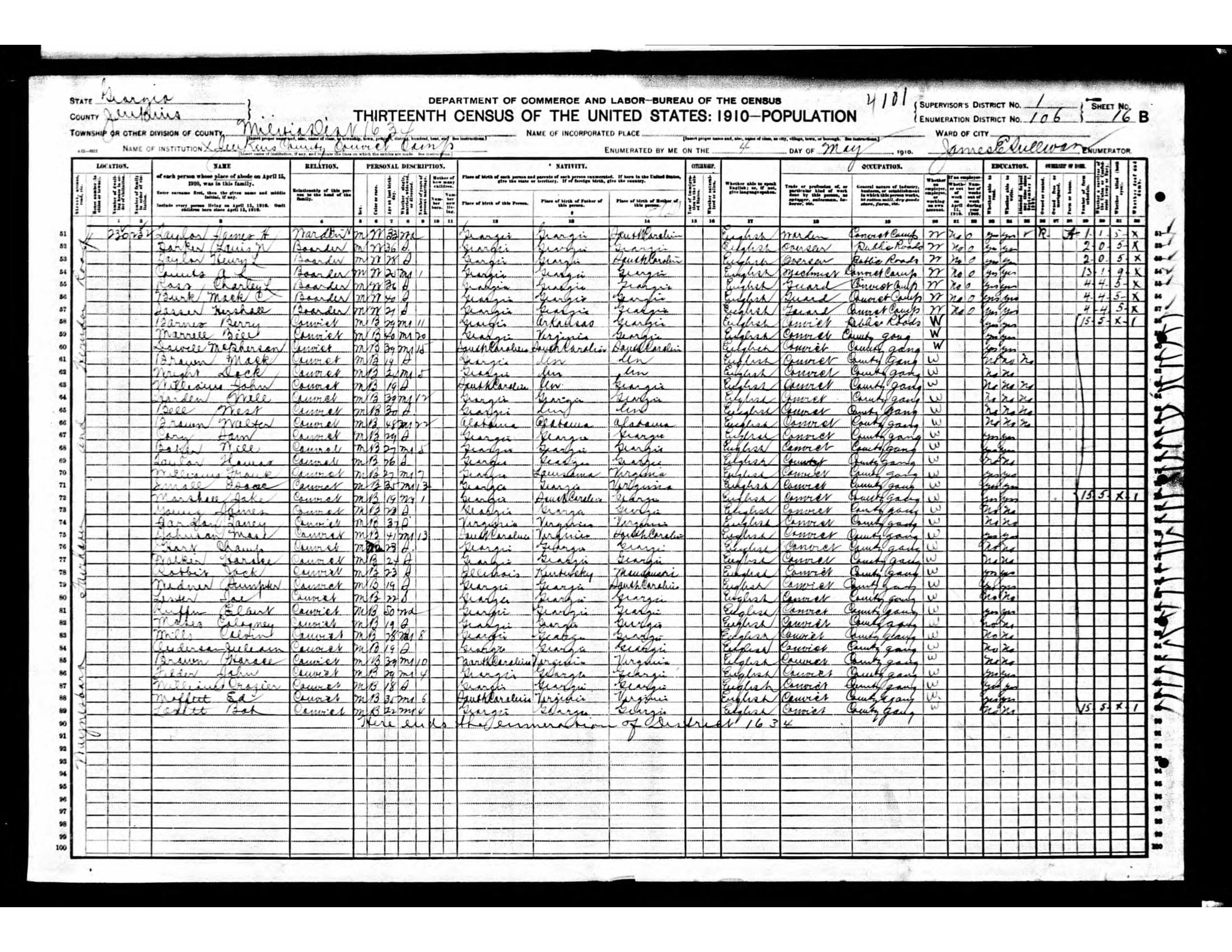

Crozier Williams was born in Waynesboro, Georgia, on March 1, 1895. He had one sister Lizzie. Before the First World War, Williams was arrested at the age of eighteen and held at the Jenkins County Convict Camp in Militia District 1634 in Georgia.1 It is possible that during his time in prison, Williams worked for a chain gang. Chain gangs were large groups of mostly black convicts lent out to the community to build public works, particularly roads.2

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Southern states were attempting to build better roads. However, such projects required a large workforce. Prisoners were a population easily exploited. In 1908, Georgia law banned the convict lease system created during the rise of Jim Crow and thus gave birth to the chain gang.3 By 1910, the concept of the chain gang was common in the South. While it is uncertain what Crozier Williams was subject to during his time in prison, his industry is listed on line 87 of his 1910 United States Federal Census as county gang, as seen in the census record, meaning that it is very possible that he worked in some capacity in a chain gang. He was later released and lived in Sebring, Florida, before he joined the military.4

Military Service

In 1917, three years after World War I began in Europe, President Woodrow Wilson declared war on Germany with the approval of Congress. The government quickly realized they needed to muster a larger army to send to the European war front. On May 17, 1917, Congress passed the Selective Service Act. The act required all male citizens between the ages of twenty-one and thirty to register for the draft. Williams registered for the draft on June 5, 1917. He later was drafted into the Army on June 20, 1918, and was sent to train at Camp Dix in New Jersey.5

About thirteen percent of the United States Army in World War I was African American. However, most African Americans served in noncombatants units. The Southern states in particular were fearful of black men learning how to shoot guns, so they were often times relegated to Quartermaster and Engineer units. Crozier Williams served as a part of Company E, 807th Pioneer Infantry, which implied these were armed infantry soldiers. The 807th Pioneer Infantry was formed at Camp Dix in late July of 1918. They were sent overseas in September and took part in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. While Pioneer Infantry regiments served in technical roles such as constructing and repairing bridges and railroads, they often served on the front lines of combat as these units experienced direct action with the enemy. This regiment was sent to the front to build bridges, but in reality they often times did see combat. The 807th received credit for it participation in the Meuse-Argonne campaign, the largest battle the US Army ever fought. When the battle ended victoriously, the war ended. 6

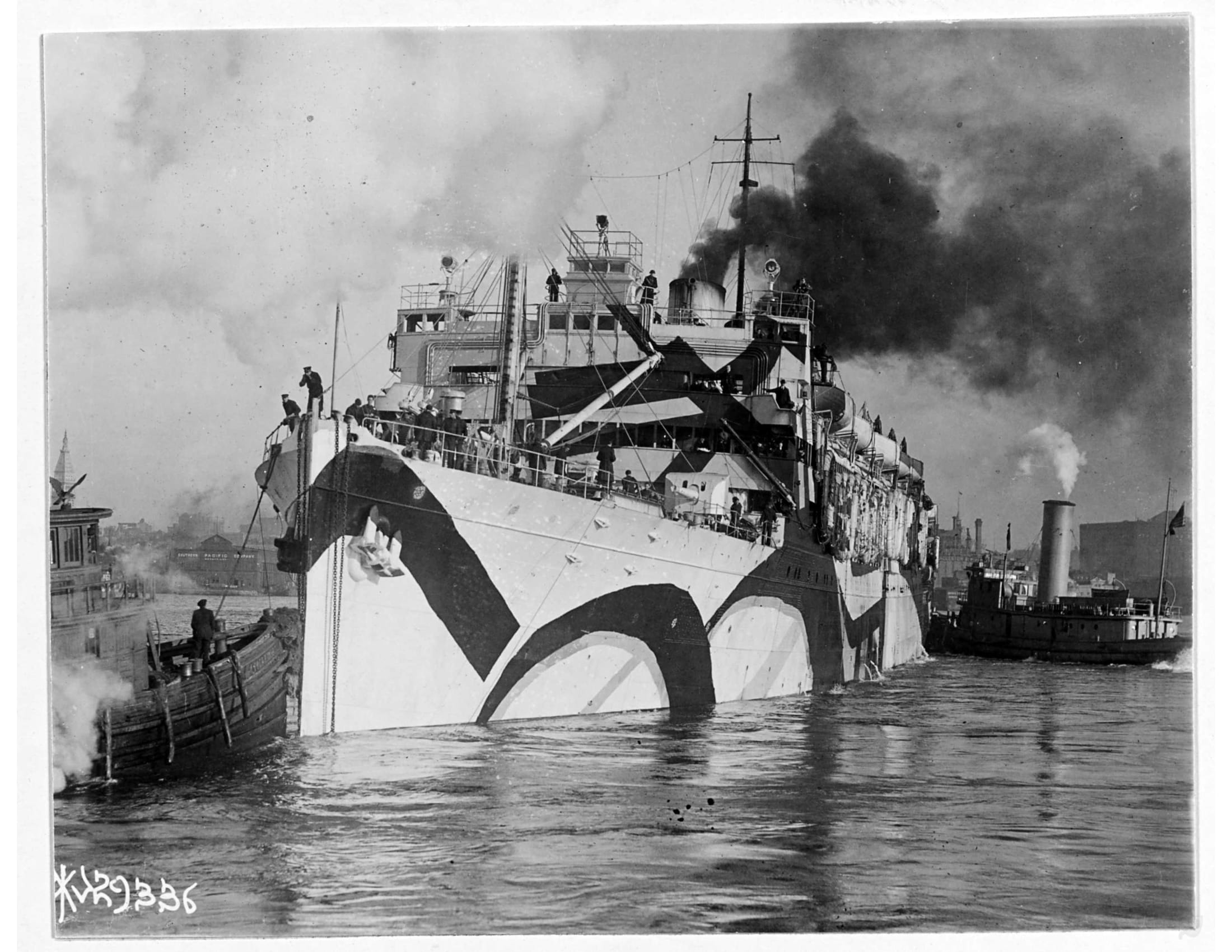

Williams served overseas from September 4, 1918, until July 3, 1919, in France. Williams received a promotion to the rank of Sergeant on March 25, 1919. An impressive accomplishment for a member of a chain gang. After the war, he departed France on the USS Orizaba, as pictured here, alongside other members of the 807th Pioneer Infantry Regiment. The regiment returned to Camp Dix and was disbanded. Williams received an honorable discharge on July 11, 1919.7

Post Service Life

After the war, Crozier settled in Waycross, Georgia, with his wife Neomia and found work as a brakeman. A brakemen’s responsibilities involved climbing atop trains and manually turning a large brake control to engage the train’s brakes in cases where air brakes failed to work. Brakemen experienced hazardous working conditions where they regularly risked their lives to stop trains. Williams died on October 15, 1948, and was interred on October 19, 1948 at the Saint Augustine National Cemetery in Saint Augustine, Florida. He is buried in Section D, Grave 77.8

Endnotes

1 “Georgia, World War I Service Cards, 1917-1919,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com : accessed July 26, 2018), entry for Eddie Landrum; “U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists,” database, Ancestry.com (http://ancestry.com: accessed July 26, 2018), entry Crozier Williams; “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (http://ancestry.com: accessed July 26, 2018), entry for Crozier Williams; “1930 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com : accessed July 26, 2018), entry for Crozier Williams.

2 Alex Lichtenstein, “Good Roads and Chain Gangs in the Progressive South: "The Negro Convict is a Slave," The Journal of Southern History 59, no. 1, (February 1993): 86-87,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2210349.

3 Sarah Haley, “Like I Was a Man”: Chain Gangs, Gender, and the Domestic Carceral Sphere in Jim Crow Georgia,” Signs 39, no. 1, Women, Gender, and Prison: National and Global Perspectives (Autumn 2013): 53, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/670769.

4 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” Ancestry.com, Crozier Williams.

5 Jennifer D. Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 1; “Records of the Selective Service System (World War I),” National Archives, accessed July 26, 2018, https://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/163.html#163.4; “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” Ancestry.com, Crozier Williams. ”U.S., Lists of Men Ordered to Report to Local Board for Military Duty, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (http://ancestry.com: accessed July 26, 2018), entry for Crozier Williams.

6 Keene, World War I, 93-95; Derrel B. Depasse, Traveling the Rainbow: The Life and Art of Joseph E. Yoakum (New York/Jackson, MS: Museum of American Folk Art/University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 11; “Georgia, World War I Service Cards, 1917-1919,”Ancestry.com, Crozier Williams; “Return of the 807th Pioneer Regiment,” UMassAmherst, accessed July 26, 2018, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/pageturn/mums312-b219-i282/#page/1/mode/1up; Eric Page, “Herbert Young, Who Fought In World War I, Dies at 112,” The New York Times, April 28, 1999, https://www.nytimes.com/1999/04/28/nyregion/herbert-young-who-fought-in-world-war-i-dies-at-112.html.

7“U.S. Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists,” Ancestry.com, Joseph Williams; Page, “Herbert Young, Who Fought In World War I”; “U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists,” Ancestry.com, Crozier Williams; Page, “Herbert Young, Who Fought In World War I”.

8 “U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com: accessed July 26, 2018), entry for Crozier Williams; “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com : accessed July 24, 2018), entry for Crozier Williams; Stephen Skye, “The Life of a Brakeman,” The Neversink Valley Museum of History & Innovation, 2009, accessed July 19, 2017, http://neversinkmuseum.org/articles/the-life-of-a-brakeman/.

© 2018, University of Central Florida