Russell Bagby Palmes Jr. (September 16, 1916-April 24, 1945)

Chief Storekeeper, USS Frederick C. Davis, US Navy

By Amanda M. Sykes and John Lancaster

Early Life

Russell Bagby Palmes Jr. was born on September 19, 1916, in Tyrone, Grant County, NM, the oldest child of Russell Bagby Sr. and Golda (née Love) Palmes.1 Russell Sr. was born in 1887 in Jackson County, MS to a second-generation immigrant family, as his grandfather hailed from Spain.2 Russell Sr. and his siblings grew up in Mississippi where their father, Jeremiah, worked as a lumber inspector at a mill in Wayne County.3 Russell Sr. also entered the lumber industry in Mississippi as a young man, working as a bookkeeper for a sawmill in 1910, six years before Russell Jr.’s birth.4 The lumber industry reached its peak in Mississippi during this period, as the state produced nearly three billion board feet of lumber in 1909. By the late 1920s, as the industry continued to grow, Mississippi produced the most lumber in the US.5 Russell Jr.’s mother, Golda, was born in Kentucky in 1895.6 In 1910, she lived with her parents, three siblings, and a sixteen-year-old servant named Murtie Lester on a farm the family owned in Metcalfe County, KY. Her father Robert worked the land on this farm while her mother Cora Ellen worked as a clerk in a general store, each laboring in tandem to financially provide for their family.7

On May 15, 1915, Russell Sr. and Golda married in Kentucky. Shortly afterward, the couple relocated to New Mexico, where they welcomed Russell Jr. in September 1916.8 New Mexico experienced an influx of immigrants from the eastern states after it became the forty-seventh state admitted to the Union in 1912.9 By Russell Jr.’s birth in 1916, the first World War had entered its second year in Europe. Though the US took an isolationist stance at the start of the war, they inched closer to joining after a series of aggressive German actions, including the May 7, 1915 sinking of the passenger liner RMS Lusitania by German submarines, which killed 128 Americans. On April 6, 1917, the US declared war on Germany and officially joined the First World War.10 One month later, on May 18, 1917, Congress passed the Selective Service Act, which initially required all men between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-one to register for the draft.11 Russel Sr., now living with his family in Mobile, AL, registered for the draft on June 15, 1917. At the time, he worked as a bookkeeper for a local railroad. Russell Sr. filed for an exemption from military service at the time of his registration, claiming that he remained the sole provider for his wife and Russell Jr.12 The government either granted him an exemption or never called him into the military, as he did not serve.13

The Palmes family migrated southwards to Florida in the years that followed. In August 1919, Russell Sr. and Golda welcomed their second son, Jere, in Pensacola, FL, before settling in St. Augustine, FL sometime after 1920.14 The family continued to grow with the arrivals of four more children following Russell and Jere, including Ellen (born 1922), Welton (born 1927), Betty (born 1928), and Mary (born 1931).15 Betty, their second daughter, was adopted. Living with the Palmes family as a lodger in 1930, by 1935 Russell Sr. and Golda had adopted Betty as their own daughter.16

Though Florida experienced a land boom in the early 1920s, around the period the Palmes moved to the state, a number of issues began to affect Florida’s economy by the middle of the decade. Devastating hurricanes hit the state in 1926 and 1928 and damaged Florida’s growing tourism industry. Additionally, an infestation of Mediterranean fruit flies in 1929 curbed citrus production, which hurt the state economy.17 The start of the Great Depression following the stock market collapse in October 1929 exacerbated these issues for many Floridians. Despite these challenges, however, Russell Sr. worked as a clerk with the Florida East Coast Railroad, a position he maintained throughout the 1930s.18 His stable employment allowed the Palmes children to enjoy a relatively stable upbringing amidst the global economic hardships of the era. In 1930, for example, the family owned their home on John St., just two miles west of St. Augustine’s historic district.19 Ten years later, in 1940, they managed to own the same home, an impressive feat for the time.20

Russell Jr. and his siblings attended school throughout their lives.21 Their mother, Golda, highly valued her children’s education. In 1924, she became president of the first organized Parent Teacher Association in St. Johns County, at West Augustine School. Russell Jr. graduated from Ketterlinus High School in 1934, and shortly thereafter worked as a doorman and floor manager at Matanzas Theatre, a movie theater in St. Augustine.22 In September 1940, Congress passed the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, which instituted the first peacetime draft in US history. The act required all males between the ages of twenty-one and forty-five to register for potential military service.23 When Russell Jr. registered for the draft on October 16, 1940, he still worked at Matanzas Theatre.24

Military Service

World War II began in September 1939 with the German invasion of Poland.25 Similar to the nation’s response to joining the First World War in 1914, most of the US population favored neutrality in this new global conflict. Despite this stance, the US government recognized the need to build up and ready its military for potential entry into the war. For instance, on June 14, 1940, Congress passed the Naval Expansion Act, which authorized the construction of new vessels and aircraft that totaled an eleven percent increase in US naval tonnage.26 Though he remained committed to neutrality for the next year and a half, President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked Congress to declare war on Japan following the December 7, 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. The attack incentivized the US population and its governing officials to join the war effort.27 The US declared war on Japan on December 8, 1941. On December 11, Germany and Italy, then allied with Japan, declared war on the US, and the nation officially entered World War II.28

On January 15, 1942, just one month after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Russell enlisted in the US Navy in Jacksonville, FL. After his initial training as a sailor, Russell trained as a storekeeper.29 He arrived at the Submarine Chaser Training Center in Miami, FL on June 13, 1942, where he further practiced his duties in the stock room.30 Storekeeper responsibilities centered primarily on maintaining supplies aboard vessels that ranged from equipment, tools, consumables, clothing, parts, and other miscellaneous items.31 Russell excelled at his duties here, and reached the rank of Storekeeper 2nd Class on March 5, 1943.32 During this time, Russell also married his hometown sweetheart, Mary Charlene Whitten, a trained nurse and native Floridian.33 He returned to St. Augustine, FL to marry her on November 7, 1942.34

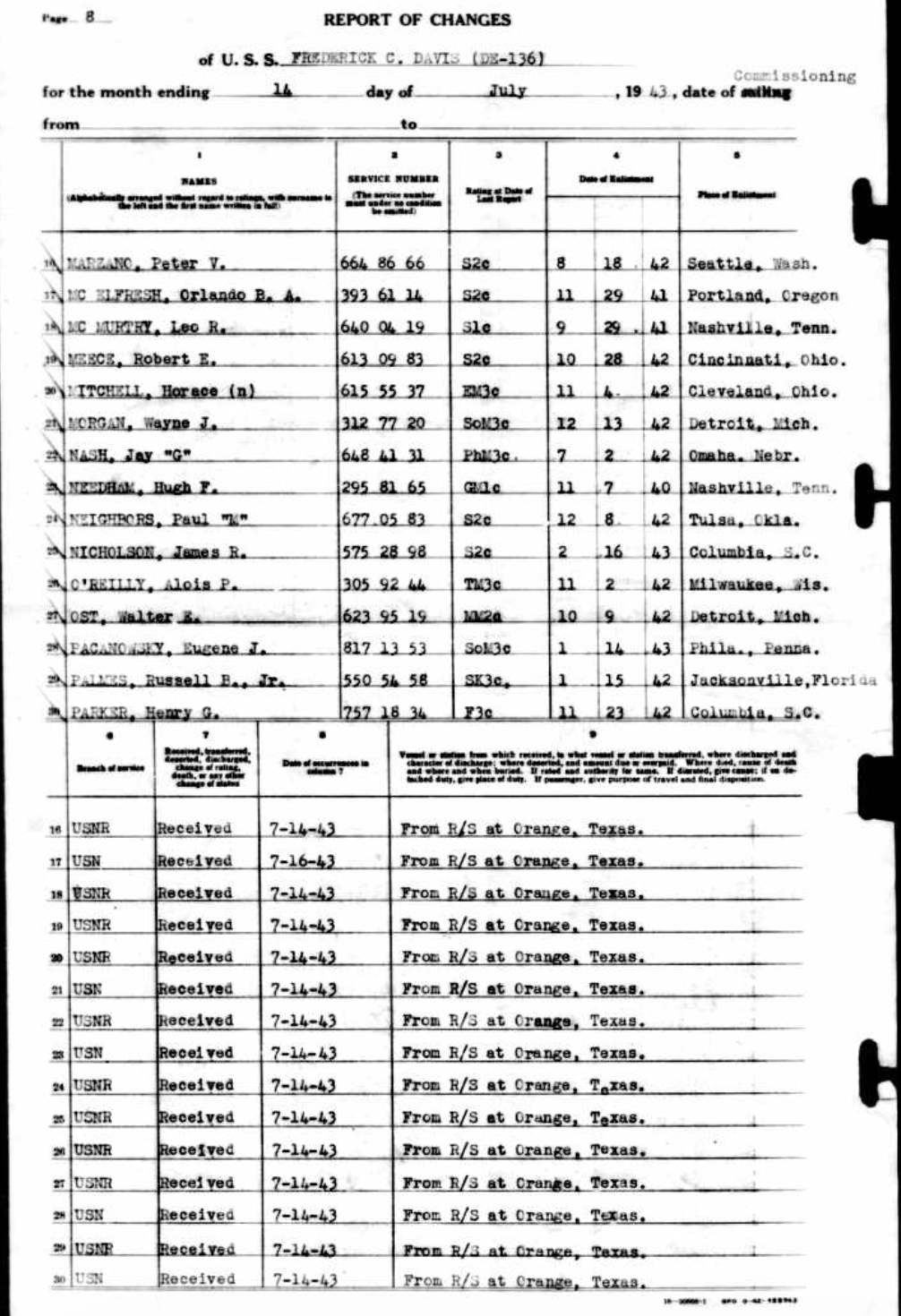

On May 8, 1943, Russell left the Submarine Chaser Training Center in Miami and departed for Naval Station (NS) Orange in Orange, TX.35 NS Orange sat along the Sabine River in eastern Texas, near the Louisiana border. The Sabine River provided the station direct access to the Gulf of Mexico. During World War II, NS Orange served as the construction site for ninety-three destroyer escort ships, including the USS Frederick C. Davis (DE-136).36 Named for Ensign Frederick C. Davis, who earned the Navy Cross for making the ultimate sacrifice while defending the USS Nevada during the attack on Pearl Harbor, the ship launched on July 14, 1943.37 Russell joined the crew aboard the USS Frederick C. Davis on this date, where he continued to serve as one of the ship’s storekeepers, as seen on the Navy Muster Roll here.38

Between late 1943 and April 1945, the Davis and her crew performed their mission to protect ships in fire support areas from enemy submarines and aircraft.39 On October 7, they sailed from Norfolk, VA on a mission to escort a convoy to Algiers, Algeria. Once in the Mediterranean, the Davis’s crew engaged in their first combat maneuvers against enemy aircraft. During this assault, on November 6, 1943, they helped defend Allied ships against torpedo and bomber attacks.40 In January 1944, the Davis helped escort Allied invasion forces for their landings at Anzio, a coastal town in Italy about forty miles south of Rome. The Allies launched their invasion at Anzio on January 22, 1944, and fought violently against Axis powers for nearly six months to move north toward Rome. Finally, in early June, Allied troops liberated Rome.41 The USS Frederick C. Davis constantly patrolled the Anzio beachhead for these six months, providing naval support against enemy shellfire from the shore and helping to jam German radio frequencies. Following the Anzio operation, the US Navy awarded the crew of the Davis the Navy Unit Commendation for their actions during the battle. Additionally, on June 1, 1944, Russell received a promotion to the rank of Chief Storekeeper.42

After completing more patrolling duties in the waters around southern France, the Davis returned to New York Navy Yard on September 19, 1944 for repairs. The ship and her crew remained there until January 1945, during which time Russell returned to St. Augustine to visit his wife and family.43 In the latter months of the war, Russell and his fellow crewmates aboard the Davis played a significant role in Operation Teardrop, which aimed to protect the US from German submarine attacks. Operation Teardrop formed after the Allies decoded German intelligence that outlined a planned submarine attack on the US East Coast.44 After military personnel completed her repairs in January 1945, the Davis sailed from New York to intercept these enemy forces. The Davis and additional ships in her formation saw outstanding success after putting a stop to five enemy submarines throughout the early spring of 1945.45

On the morning of April 24, 1945, the USS Frederick C. Davis identified the German U-boat U-546, as it snuck through a barrier about 640 miles northwest of the Azores, about one thousand miles off the coast of mainland Portugal. At 8:29 AM, U-546 entered within two thousand yards of the Davis. The crew of the Davis noticed the U-boat, but lost sight of it as it quickly descended below the waves while between the Davis and an additional Allied escort destroyer, the USS Hayter. Ten minutes passed before the crew relocated U-546, by that time only 650 yards away. Typically, when a ship identifies an enemy vessel at close range, a general alarm sounds to notify the men aboard to man their stations. A failure occurred aboard the Davis when this alarm did not sound, which left many crewmembers disoriented and unprepared. Those at the ready attempted to turn their vessel out of range, but U-546 fired a torpedo that struck the USS Frederick C. Davis on her port side. Despite efforts to control the damage, the engine, forward living, and storage compartments flooded. Additional damage to the fire suppression mains prevented the crew from extinguishing fires that started around the ship. Within just fifteen minutes, the USS Frederick C. Davis snapped in two and sank. About one hundred of the crew leapt into the Atlantic Ocean. In the ensuing chaos, depth charges, anti-submarine explosives designed to trigger at specific ocean depths, detonated and killed about twenty sailors in the water. Of the 195 crewmen aboard the USS Frederick C. Davis, only seventy-seven survived the attack.46

Unfortunately, Chief Storekeeper Russell B. Palmes went down with the ship and lost his life during the assault. Because Russell’s remains could not be recovered, the Navy initially listed him as Missing in Action, before finally declaring him Killed in Action by the end of April, 1945.47 Around ten hours after the attack, the Davis’ sister ship, the USS Flaherty, sought vengeance on U-546 and succeeded.48 The Flaherty took the U-boat captain and its crew prisoner.49

Legacy

Although World War II did not end until September 1945, the Victory in Europe (VE-Day) took place on May 8, 1945, just two weeks after Chief Storekeeper Russell Palmes lost his life. VE-Day consisted of two surrender signings by Germany and marked the end of most fighting across Europe.50 Because the attack that claimed Russell’s life occurred just two weeks before VE-Day, the USS Frederick C. Davis became the last US Naval vessel lost in the Battle of the Atlantic.51

Although Russell’s life ended tragically, his legacy continues in a multitude of ways. On October 10, 1945, Russell’s widow Mary Charlene welcomed the birth of their daughter, Michelle, born six months after Russell’s death.52 During his time in the Navy, Russell greatly impacted his fellow Veterans and crewmates. In a letter sent to his widow Mary on June 7, 1945, Ensign Robert E. Minerd, the senior surviving officer aboard the USS Frederick C. Davis, expressed that he would remember Russell “as a loyal warm-hearted shipmate whose depth of human understanding and consideration were quite remarkable.”53 For his service and sacrifice, Russell also earned a Purple Heart.54 Those who have earned Purple Hearts lost their lives or became wounded by enemy action while serving in the US military.55 During World War II, the military awarded over one million Purple Hearts, more than all other twentieth-century conflicts combined.56

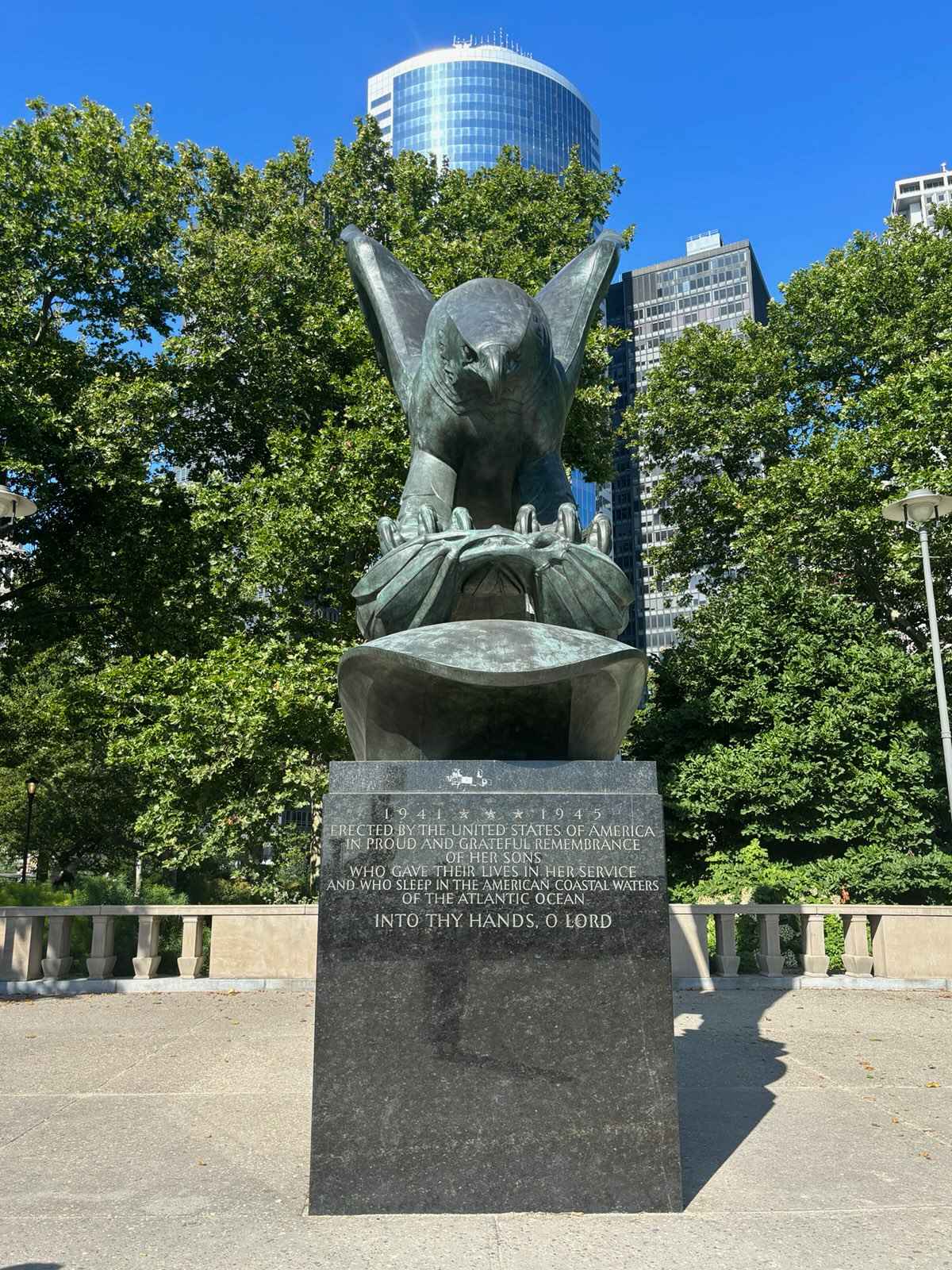

Numerous monuments and memorials across the country also pay respect to those who have fallen while in service. The American Battle Monuments Commission’s World War II East Coast Memorial, part of which can be seen in the photograph here, honors Veterans of the Second World War who lost their lives in the western waters of the Atlantic Ocean.57 Located in Battery Park, New York City, and dedicated in 1963 by President John F. Kennedy, the memorial includes eight granite pylons inscribed with the names of each Veteran missing in the coastal waters of the Atlantic. Russell remains one of over 4,600 service members whose names appear on the memorial.58 Russell’s name also appears on the World War II Memorial located in downtown St. Augustine, FL. Dedicated by the St. Augustine Pilot Club in 1946 to memorialize those killed during the war from St. Johns County, Russell’s name appears alongside his brother Jere’s, who also died in battle.59

Jere Francis Palmes served as a Captain in the 222nd Infantry Regiment, 42nd Infantry Division, also known as the “Rainbow Division.”60 On April 25, 1945, just hours after his brother Russell died, Jere lost his life while bravely repelling enemy forces in Donauwörth, Germany.61 Jere’s comrades originally buried him in a temporary cemetery that later became the American Battle Monuments Commission’s Lorraine American Cemetery in Saint-Avold, France.62 In 1949, his family rreinterred him in St. Augustine National Cemetery, where he now rests in Section D, Plot 94.63 In the years following the war, Russell Sr. and Golda advocated for Russell to receive recognition for his military service, including a marker at St. Augustine National Cemetery.64 Today, a cenotaph for Russell exists on the reverse side of his brother Jere’s headstone, where his legacy persists.65

The youngest Palmes brother, Welton, was drafted into the US Army late in the war; however, after Golda and Russell Sr. intervened on the grounds that they had already lost two children in the conflict, Welton did not go overseas.66 His family laid him to rest in St. Augustine National Cemetery when he died in 1991.67 In 1975, Golda Palmes honored her sons Russell and Jere at a flagpole illumination ceremony at St. Augustine National Cemetery. Cemetery officials invited Golda to throw the switch, which illuminated the flag and, figuratively, illuminated the memories of all those buried there. As a Double Gold Star mother, cemetery administrators asked Golda to perform the honor. Individuals receive Gold Star designations as a result of losing family members in active conflict.68 In a touching tribute to her two sons Russell and Jere, as well as to all the Veterans buried at St. Augustine National Cemetery, Golda remarked at the ceremony, “it’s a simple thing, flipping a switch to light up our flag, but it is a great thing to me to be given the duty of doing this to remember our honored dead in this little cemetery.”69

Endnotes

1 “Florida 1935 Population Census,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org: accessed April 14, 2024), entry for Russell Bagby Palmes Jr.; “Florida Draft Registration for WWII,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org: accessed April 14, 2024), entry for Russell Bagby Palmes, St. Augustine, FL.

2 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 14, 2024), entry for Russell B Palmes, Mobile, AL; “Mississippi 1900 Population Census,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org: accessed April 14, 2024), entry for Russell Bagby Palmes, Wayne County, MS.

3 “Mississippi 1900 Population Census,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org: accessed April 14, 2024), entry for Russell Bagby Palmes, Wayne County, MS.

4 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 12, 2024), entry for Russell Palmes.

5 James E. Fickle, “Forests and Forest Products Before 1930,” Mississippi Encyclopedia, modified April 14, 2018, accessed June 6, 2024, https://mississippiencyclopedia.org/entries/forests-and-forest-products-before-1930/.

6 “Golda Love Palmes,” FindAGrave, July 14, 2010, accessed March 2, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/54953614/golda_love_palmes

7 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 12, 2024), entry for Golda Love.

8 “Marriage Certificate 1915,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org: accessed April 14, 2024), entry for Russell Bagby Palmes and Golda Love, KY.

9 “New Mexico Art Tell New Mexico History,” New Mexico Museum of Art, accessed June 27, 2024, https://online.nmartmuseum.org/nmhistory/people-places-and-politics/statehood/history-statehood.html.

10 “A World at War - Timeline (1914 - 1921),” Library of Congress, accessed April 14, 2024, https://www.loc.gov/collections/stars-and-stripes/articles-and-essays/a-world-at-war/timeline-1914-1921/#.

11 “World War I Draft Registration Cards,” National Archives, July 15, 2019, April 14, 2024, https://www.archives.gov/research/military/ww1/draft-registration.

12 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” entry for Russell B Palmes.

13 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 12, 2024), entry for Russell B Palmes, St. Johns County, FL.

14 “Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 14, 2024), entry for Jere Palmes; “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 12, 2024), entry for Russell B Palmes, Escambia County, FL; “Golda Palmes dies at age 102,” St. Augustine Record, December 30, 1997.

15 “Florida 1940 Census,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org: accessed April 14, 2024), entry for Mary Palmes, St. Johns County, FL.

16 “1930 United States Federal Census,” entry for Russell B Palmes; “1935 Florida State Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed April 4, 2024), entry for Betty Palmes; Respondents for Betty on the 1930 US Federal Census claim not to know where she nor her parents were born, which further suggests the Palmes family adopted her sometime between 1930 and 1935.

17 “The Great Depression in Florida,” Florida Department of State, 2024, accessed April 14, 2024. https://dos.fl.gov/florida-facts/florida-history/a-brief-history/the-great-depression-in-florida/.

18 “1930 United States Federal Census,” entry for Russell B Palmes, St. Johns County, FL; “Florida 1940 Census,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org: accessed April 14, 2024), entry for Russell B Palmes, St. Johns County, FL; “Once a Graduate… An Allumni Forever,” Hall of Fame Galleries, 2018, accessed April 14, 2024. https://www.mysahs.com/hall-of-fame-galleries/.

19 “1930 United States Federal Census,” entry for Russell B Palmes.

20 “Florida 1940 Census,” entry for Russell B Palmes.

21 “Florida 1945 Population Census,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org: accessed April 14, 2024), entry for Russell Palmes, St. Augustine, FL.

22 Gregory A. Moore, Sacred Ground: The Military Cemetery at St. Augustine (St. Augustine: Florida National Guard Foundation, 2013), 148.

23 “History of the Selective Service System,” Selective Service System, accessed June 27, 2024, https://www.sss.gov/history-and-records/.

24 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed March 14, 2024), entry for Russell Bagby Palmes.

25 “World War II Dates and Timeline,” United States Holocaust Museum Holocaust Encyclopedia, November 15, 2021, accessed April 14, 2024. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/world-war-ii-key-dates.

26 “Naval Expansion Act, 14 June 1940,” Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed June 27, 2024, https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1941/prelude/naval-expansion-act-14-june-1940.html.

27 “Research Starters: The Draft and World War II,” The National WWII Museum, accessed April 14, 2024. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/students-teachers/student-resources/research-starters/draft-and-wwii.

28 “December 1941,” Franklin D. Roosevelt, Day by Day: A Project of the Pare Lorentz Center at the FDR Presidential Library, accessed June 27, 2024, http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/daybyday/event/december-1941-9/.

29 Moore, Sacred Ground, 148; “U.S. World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed 22 May 2024), entry for Frederick C. Davis, World War II, July 1943; “U.S. World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed 22 May 2024), entry for Frederick C. Davis, World War II, March 1944.

30 Moore, Sacred Ground, 148.

31 Warren A. Rainey, “Storekeeper Basic - Nonresident Training Course,” 2002, accessed April 14, 2024, 9. https://navytribe.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/navedtra-14326.pdf.

32 Moore, Sacred Ground, 148.

33 Moore, Sacred Ground, 149.

34 “Marriage Certificate 1942,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org: accessed April 14, 2024).

35 “U.S. World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949,” entry for Frederick C. Davis, July 1943; Guy J. Nasuti, “Frederick C. Davis (DE-136),” Naval History and Heritage Command, December 17, 2019, accessed June 28, 2024, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/f/frederick-c-davis-de-136.html.

36 “Orange,” Naval History and Heritage Command, August 17, 2015, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=116193.

37 Nasuti, “Frederick C. Davis (DE-136).”

38 “U.S. World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949,” entry for Frederick C. Davis, July 1943.

39 Nasuti, “Frederick C. Davis (DE-136).”

40 Moore, Sacred Ground, 149.

41 “Anzio: The Invasion that Almost Failed,” Imperial War Museums, accessed June 28, 2024, https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/anzio-the-invasion-that-almost-failed.

42 Moore, Sacred Ground, 150.

43 Moore, Sacred Ground, 151, 156.

44 “H-047-1: The Last Battle of the Atlantic–Operation Teardrop,” Naval History and Heritage Command, accessed June 28, 2024, https://www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-047/h-047-1.html.

45 “U.S.S. ‘Frederick C. Davis’, Last Warship Lost in the European Theater WWII,” c 1944, Assession 08-003, Box 1, Philip K. Lundeberg Papers, Smithsonian Institution Archives, https://siarchives.si.edu/collections/siris_sic_11847.

46 “Frederick C. Davis (DE-136),” Naval History and Heritage Command.

47 “U.S. World War II Navy Muster Rolls, 1938-1949,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed 22 May 2024), entry for Frederick C. Davis, World War II, April 1945.

48 “Frederick C. Davis (DE-136),” Naval History and Heritage Command.

49 “Operation Teardrop,” Codenames Operations of World War II, modified February 2, 2024. https://codenames.info/operation/teardrop/.

50 “Victory in Europe Day: Time of Celebration, Reflection,” US Department of Defense, accessed April 14, 2024, https://www.defense.gov/Multimedia/Experience/VE-Day/#top.

51 “Frederick C. Davis (DE-136),” Naval History and Heritage Command.

52 Moore, Sacred Ground, 156.

53 Ensign Robert E. Minerd to Mary C. Palmes, June 7, 1945.

54 “Russell B Palmes Jr.,” National Purple Heart Hall of Honor, accessed June 18, 2024, https://www.thepurpleheart.com/roll-of-honor/profile/default?rID=20b80f75-af60-4f64-b997-0f1b678d526c.

55 Danielle DeSimone, “9 Things You Need to Know About the Purple Heart Medal,” United Service Organization, August 4, 2023, accessed June 28, 2024, https://www.uso.org/stories/2276-8-purple-heart-facts.

56 Claudette Roulo, “The Purple Heart: America's Oldest Medal,” US Department of Defense, August 7, 2023, accessed June 28, 2024, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/1650949/the-purple-heart-americas-oldest-medal/.

57 UCF Veterans Legacy Program, World War II East Coast Memorial, photograph, 2024, Battery Park, New York City, NY.

58 “East Coast Memorial” Cemetery Records Online, accessed April 14, 2024. https://www.interment.net/data/us/ny/new-york/east-coast-memorial/records-o-r.htm; “The Battery - East Coast Memorial,” New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, accessed April 14, 2024, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/battery-park/monuments/1929; “East Coast Memorial,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed July 19, 2024, https://www.abmc.gov/East-Coast-Memorial.

59 “World War II Memorial, St. Johns County, Florida,” The Historical Marker Database, accessed June 28, 2024, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=143655.

60 Because Americans from all over the country came together to serve in the 42nd ID, the division was commonly known as a Rainbow Division; Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide: Preliminary Abridged Edition (St. Augustine, FL: St. Francis Barracks Special Archives, 1989), 204; “Russel Bagby Palmes Jr.,” FindAGrave, June 19, 2011, accessed March 2, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/71611500/russell_bagby_palmes.

61 “Capt. Jere Palmes Killed In France on April 25th,” St. Augustine Record, May 9, 1945.

62 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 31, 2024), entry for Jere F. Palmes; “Lorraine American Cemetery,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed May 31, 2024, https://www.abmc.gov/Lorraine.

63 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for Jere F. Palmes.

64 R. B. Palmes to J.A. Ulio, July 3, 1945.

65 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide, 204.

66 Paul Mitchell, “Double Gold Star Mother Throws Switch Illuminating Flagpole,” St. Augustine Record, August 26, 1975, 1.

67 “Welton Wade Palmes,” FindAGrave, March 3, 2000, accessed July 1, 2014, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/3964866/welton-wade-palmes?_gl=1*1bkcpw4*_gcl_au*MjUyNDQ4NDQ2LjE3MTY5MDU1ODk.*_ga*MjA4NTMzNTA0Ni4xNzE2OTA1NTkx*_ga_4QT8FMEX30*YjQ

© 2024, University of Central Florida