Elias Rose (1809–1837)

By Matt Patsis

Early Life

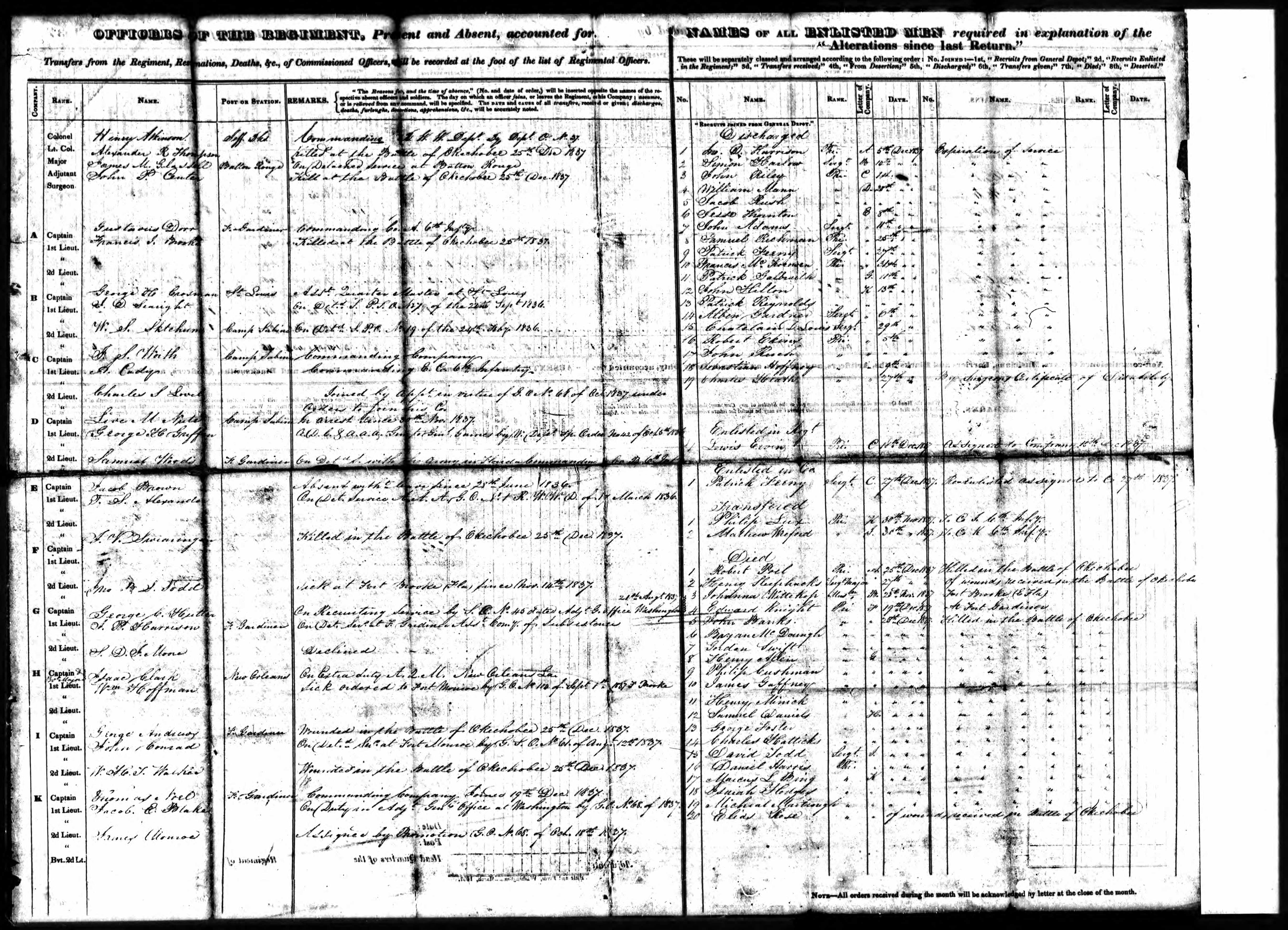

Elias Rose was born in Morgan, Virginia (now West Virginia) in 1809. While little is known about Rose’s early life, he indicated on his enlistment form, shown here, that he worked as a farmer prior to joining the army. Rose enlisted in 1837 in Baltimore at the age of twenty-eight.1

Military Service

The army that Private Rose belonged to was very different than the twenty-first century US Army. It was much smaller with about 7,200 soldiers in its ranks organized into twelve regiments composed of four artillery, seven infantry, and one dragoon or cavalry regiments. Approximately 6,600 of these soldiers were enlisted men and about 600 were officers. This small army was scattered in fifty-three separate installations around the nation. Just before the Seminole War, 500 soldiers garrisoned ten bases across northern and central Florida. Many of these men were immigrants because soldiers, wherever they served, were poorly paid; they received five dollars a month. A civilian laborer made much more. As a result, recently arrived immigrants, who needed work filled the ranks. As a result of the Second Seminole War (1835-1842), the regular Army almost doubled in size. Despite this expansion, 30,000 militia (part-time soldiers) and volunteer (newly-recruited) units reinforced the regular Army units in their campaigns in Florida against the Seminoles.2

Fought between 1835 and 1842, the Second Seminole War was part of a larger conflict between Native Americans in Florida and the United States military that lasted from 1816 to 1858. In alignment with the goals of the Indian Removal Act (1830), the United States government sought to move all the Florida Native Americans, collectively—though inaccurately—referred to as Seminoles, from the peninsula to the Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma). Fighting in a harsh environment, against a mobile foe using guerrilla tactics, and without clear frontlines, the army struggled to defeat their outnumbered enemy. While estimates vary, approximately 10,000 soldiers and as many as 30,000 militia fought against fewer than 2,000 Seminole warriors. Eventually, after seven years, the death of 1,400-1,500 soldiers in the regular army, and the expenditure of $30,000,000-$40,000,000, the United States declared victory even while some Seminoles remained in Florida. Given these hardships, the Second Seminole War is generally considered “the longest and most costly of the Indian conflicts.”3

Private Rose served with Company K of the 6th Infantry Regiment during the Second Seminole War.4 Congress officially created the 6th Infantry Regiment in 1808. The 6th Infantry first participated in the War of 1812 and then moved along the western US frontier, where the soldiers built forts and engaged in skirmishes with the Native Americans, most notably in the Black Hawk War of 1832. The US Government ordered the 6th Infantry to proceed to Florida in 1836, amidst rising tension between the United States and the Seminoles.5 Most of the 6th Infantry, under the command of Lt. Col. Alexander R. Thompson, joined a larger force led by Col. Zachary Taylor, which moved south with orders to “destroy or capture” any Seminoles they might find.6 The 6th and the 4th Infantry regiments led the attack at the Battle of Okeechobee, but the 6th Infantry bore the brunt of the Seminoles’ fire.7 They lost four officers and sixteen privates, far more than any other company in the engagement.8 Among those sixteen privates was Rose, who passed away on December 27, 1837, from injuries sustained during the battle.9

Surpassed only by Dade’s Battle in terms of casualties, the Battle of Okeechobee occurred on December 25, 1837, two years after the war began. On Christmas Day, commanding officer Colonel Zachary Taylor led approximately 800 infantry regiment troops into battle against 380-480 Seminoles who were camped on the shore of Lake Okeechobee. Though Taylor claimed this battle as a great victory, the Seminoles – who had positioned themselves in a densely wooded area with a half mile of swamp in front of them – inflicted more extensive damage to the US troops than they themselves received. After three hours of battle, the Seminoles retreated in canoes across the lake, having lost less than seven percent of their men while Col. Taylor lost over seventeen percent of his forces. Further, the Seminoles successfully slowed Taylor’s march down the Kissimmee River long enough to evacuate their women and children farther into the Everglades. Public opinion regarding the battle’s outcome was initially mixed, but the nation eventually accepted Taylor’s claim of victory, propelling him into the national spotlight and initiating his road to the presidency. 10

Legacy

Along with some 1,500 US casualties of the Second Seminole War, Private Elias Rose is memorialized at St. Augustine National Cemetery.11 On June 13, 1842, as a prelude to the formal ending of the Second Seminole War, Col. William Worth announced that the remains of the officers who fell in the war would be gathered and reinterred in the burial ground next to the St. Francis Barracks in St. Augustine. The bodies of Maj. Francis Dade and his men were interred along with other regular soldiers in three massive vaults, each covered by an ornamental pyramid constructed of native coquina stone. Two years later, a granite obelisk was erected next to the pyramids. The US Government re-designated the St. Francis Barracks burial ground as St. Augustine National Cemetery in 1881. The so-called “Dade Pyramids” and memorial obelisk are believed to be among the oldest public monuments (excluding headstones) in the national cemetery system.12

Endnotes

1 “U.S. Army, Register of Enlistments, 1798-1914,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 14, 2020), entry for Elias Rose.

2 U.S. Army, “Toward a Professional Army,” in The United States and the Forging of a Nation, 1775-1917, ed. Richard W. Stewart (Washington DC: Center for Military History, 2005), accessed January 10, 2020, https://history.army.mil/books/AMH-V1/ch07.htm.

3 C.S. Monaco, The Second Seminole War and the Limits of American Aggression (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018); John and Mary Lou Missall, The Seminole Wars: America's Longest Indian Conflict (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2004); John K. Mahon, History of the Second Seminole War (Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 1967); Quote from Jane F. Lancaster, Removal Aftershock: The Seminoles' Struggles to Survive in the West, 1836–1866 (Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee Press, 1994), 18.

4 “The U.S., Returns of Killed and Wounded in Battles, 1790-1844,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 14, 2020), entry for Elias Rose.

5 Charles Bryne, “The Sixth Regiment of Infantry,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, accessed January 16, 2020, https://history.army.mil/books/R&H/R&H-6IN.htm.

6 John K. Mahon, History of the Second Seminole War (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1967), 219; “Colonel Z. Taylor’s Account of the Battle with the Seminole Indians near the Kissimmee River, in Florida, on December 25, 1837,” 25th Cong., 2nd Sess., 1838, S. Rep. 789: 986.

7Mahon, History, 228.

8 Bryne, “The Sixth Regiment of Infantry.”

9 “U.S. Army, Register of Enlistments, 1798-1914,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 14, 2020), entry for Elias Rose.

10 John K. Mahon, History of the Second Seminole War (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1967); Mahon, History, 219; “Colonel Z. Taylor’s Account of the Battle with the Seminole Indians near the Kissimmee River, in Florida, on December 25, 1837,” 25th Cong., 2nd Sess., 1838, S. Rep. 789, Hereafter referred to as Taylor’s Report; John and Mary Lou Missal, eds., This Miserable Pride of a Soldier (Tampa: University of Tampa Press, 2005), 129

11 “The U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 14, 2020), entry for Elias Rose.

12 Sprague, Origin, Progress, and Conclusion of the Florida War, 521-522; “Saint Augustine National Cemetery,” U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, accessed January 15, 2020, https://www.cem.va.gov/cems/nchp/staugustine.asp.

© 2019, University of Central Florida