Michael Ryan (1812–1835)

By Rachel Williams

Early Life

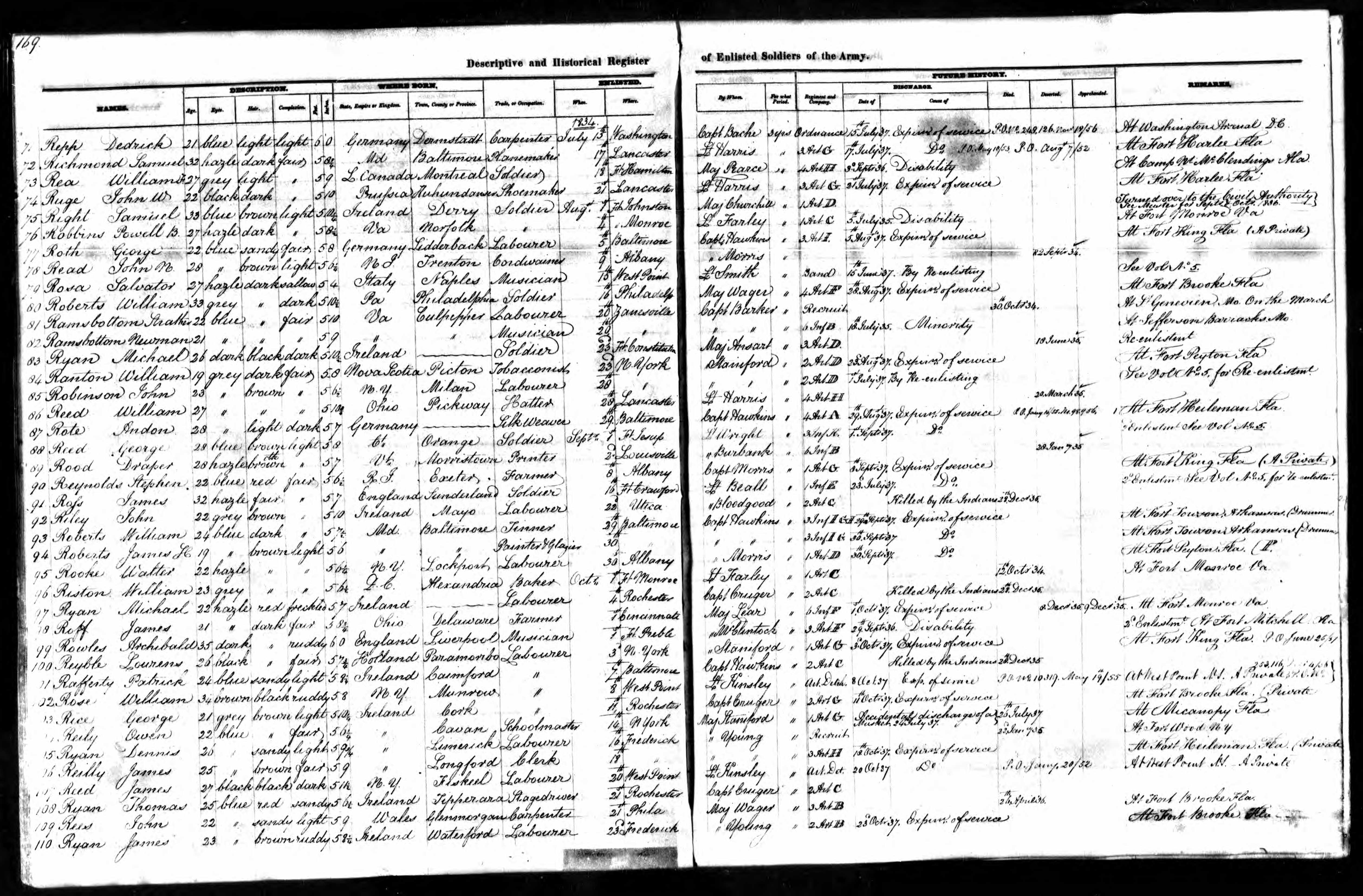

Michael Ryan was born in Ireland in 1812. Sometime prior to 1834, Ryan immigrated to the United States.1 Between the 1820s and 1860s, Irish immigrants made up one-third of immigrants into the US.2 Immigrants from Ireland faced discrimination and racism upon arrival, and competition for jobs was fierce.3 Michael worked as a laborer. At twenty-two years of age, he enlisted in the US Army out of Rochester, New York, as seen here.4

Military Service

The Army that Corporal Ryan belonged to was very different than the twenty-first century US Army. It was much smaller with about 7,200 soldiers in its ranks organized into twelve regiments composed of four artillery, seven infantry, and one dragoon or cavalry regiments. Approximately 6,600 of these soldiers were enlisted men and about 600 were officers. This small army was scattered in fifty-three separate installations around the nation. Just before the Seminole War, 500 soldiers garrisoned ten bases across northern and central Florida. Many of these men were immigrants because soldiers, wherever they served, were poorly paid; they received five dollars a month. A civilian laborer made much more. As a result, recently arrived immigrants who needed work filled the ranks. As a result of the Second Seminole War (1835-1842), the regular Army almost doubled in size. Despite this expansion, 30,000 militia (part-time soldiers) and volunteer (newly-recruited) units reinforced the regular Army units in their campaigns in Florida against the Seminoles.5

Fought between 1835 and 1842, the Second Seminole War was part of a larger conflict between Native Americans in Florida and the United States military that lasted from 1816 to 1858. In alignment with the goals of the Indian Removal Act (1830), the United States government sought to move all the Florida Native Americans, collectively—though inaccurately—referred to as Seminoles, from the peninsula to the Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma). Fighting in a harsh environment, against a mobile foe using guerrilla tactics, and without clear frontlines, the army struggled to defeat their outnumbered enemy. While estimates vary, approximately 10,000 soldiers and as many as 30,000 militia fought against fewer than 2,000 Seminole warriors. Eventually, after seven years, the death of 1,400-1,500 regular US Army soldiers, and the expenditure of $30,000,000-$40,000,000, the United States declared victory even while some Seminoles remained in Florida. Given these hardships, the Second Seminole War is generally considered “the longest and most costly of the Indian conflicts.”6

Corporal Ryan served with Company C of the 2nd Artillery Regiment during the Second Seminole War.7 Congress created the 2nd Artillery Regiment in 1821. It was formed out of the Corps of Artillery. The 2nd Artillery Regiment deployed to Florida in 1835 due to the growing tensions between the US and the Seminole people.8

In December 1835, tensions between the US military and the Seminoles were increasing. In response to these potential hostilities, Brevet Major Francis L. Dade led an expedition of 108 men from Fort Brooke (present-day Tampa) that headed north toward Fort King (near present-day Ocala) with the purpose of reinforcing the Indian Agency near there. The troops departed on December 23. Five days later, a party of 180 Seminole warriors led by Micanopy, Alligator, and Jumper ambushed the marching column just outside of modern-day Bushnell, Florida. Maj. Dade and several officers fell immediately. A 45-minute interval followed the first attack, during which the besieged US troops built a triangular breastwork of logs defended by a six-pounder cannon. Their position, however, proved indefensible. All but four out of the 108 soldiers in Dade’s Command died on the field of battle. In contrast, the Seminoles suffered only eight casualties (three killed and five wounded). The battle is generally considered to be the opening shots of the seven-year Second Seminole War.9

Of the four soldiers who survived, only three – Pvts. Ransom Clark, John Thomas, and Joseph Sprague – made it back to Fort Brooke alive.10 Pvt. Edwin DeCourcy (who traveled part of the way with Clark) died en route. Clark gave an eyewitness account of the battle, and his harrowing return, in an interview with the Boston Post, published June 6, 1837.11 Dade’s enslaved African American interpreter-guide, Luis Fatio Pacheco, also survived; he was taken prisoner by the Seminoles and recounted his own harrowing journey in interviews published many years later.12

Two months after the battle, Gen. Edmund Gaines and his men arrived at the Dade battlefield to assess the scene and bury the dead. Second Lt. James Duncan described the scene: “The first indication of our proximity to the battlefield were soldiers’ shoes and clothing, soon after a skeleton then another! then another! Soon we came upon the scene in all its horrors. The vultures rose in clouds as the approach of the column drove them from their prey, the very breastwork was black with them.”13

Legacy

Along with some 1,500 US casualties of the Second Seminole War, Corporal Michael Ryan is memorialized at St. Augustine National Cemetery in Florida.14 On June 13, 1842, as a prelude to the formal ending of the Second Seminole War, Col. William Worth announced that the remains of the officers who fell in the war would be gathered and reinterred in the burial ground next to the St. Francis Barracks in St. Augustine. The bodies of Maj. Francis Dade and his men were interred along with other regular soldiers in three massive vaults, each covered by an ornamental pyramid constructed of native coquina stone. Two years later, a granite obelisk was erected next to the pyramids. The US Government re-designated the St. Francis Barracks burial ground as St. Augustine National Cemetery in 1881. The so-called “Dade Pyramids” and memorial obelisk are believed to be among the oldest public monuments (excluding headstones) in the national cemetery system.15

Endnotes

1 “U.S. Army, Register of Enlistments, 1798-1914,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 16, 2020), entry for Michael Ryan.

2 “Irish-Catholic Immigration to America,” Library of Congress, accessed January 10, 2020, http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/irish2.html.

3 “Joining the Workforce,” Library of Congress, accessed January 10, 2020, http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/immigration/irish4.html.

4 “U.S. Army, Register of Enlistments,” Ancestry.com, entry for Michael Ryan.

5 U.S. Army, “Toward a Professional Army,” in The United States and the Forging of a Nation, 1775-1917, ed. Richard W. Stewart (Washington DC: Center for Military History, 2005), accessed January 10, 2020, https://history.army.mil/books/AMH-V1/ch07.htm.

6 C.S. Monaco, The Second Seminole War and the Limits of American Aggression (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018); John and Mary Lou Missall, The Seminole Wars: America's Longest Indian Conflict (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2004); John K. Mahon, History of the Second Seminole War (Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 1967); Quote from Jane F. Lancaster, Removal Aftershock: The Seminoles' Struggles to Survive in the West, 1836–1866 (Knoxville, TN: The University of Tennessee Press, 1994), 18.

7 “The U.S., Returns of Killed and Wounded in Battles, 1790-1844,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 14, 2020), entry for Michael Ryan.

8 W. A. Simpson, “Second Regiment of Artillery,” U.S. Army Center of Military History, accessed on January 14, 2020, https://history.army.mil/books/R&H/R&H-2Art.htm.

9 The entire detachment consisted of eight officers, 100 enlisted men, and Dade’s enslaved African American interpreter-guide, Luis Fatio Pacheco. See John T. Sprague, The Origin, Progress, and Conclusion of the Florida War (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1848), 530 and Frank Laumer, Massacre! (Gainesville, Fl.: University of Florida Press, 1968): 177-180.

10 For a privately published biography of Sprague, see Nathan W. White, Private Joseph Sprague of Vermont, The Last Soldier-Survivor of Dade’s Massacre in Florida, 28 December 1835 (Ft. Lauderdale: N.W. White, 1981).

11“Major Dade, and His Command,” The Evening Post (New York City), Aug. 30, 1842, 2.

12 Alcione M. Amos, The Life of Luis Fatio Pacheco: Last Survivor of Dade's Battle (Dade City, FL: Seminole Wars Historic Foundation, Inc., 2006).

13 Frank Laumer, Dade's Last Command (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1995), 3.

14 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed January 14, 2020), entry for Michael Ryan.

15 Sprague, Origin, Progress, and Conclusion of the Florida War, 521-522; “Saint Augustine National Cemetery,” U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, accessed January 15, 2020, https://www.cem.va.gov/cems/nchp/staugustine.asp.

© 2019, University of Central Florida