Civil War: Thirty-third United States Colored Infantry (USCI)/ First South Carolina Infantry (Colored)

By Sara Nazarian

During the first half of 1862, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton encouraged the arming of black Americans in Union-occupied territories of South Carolina under the command of David Hunter. This regiment failed because the War Department had not officially authorized its formation. Later, Stanton authorized Brigadier General Rufus Saxton to "arm, uniform, equip, and receive into the service of the United States such number of volunteers of African descent as you may deem expedient, not exceeding 5,000" in Beaufort, South Carolina. Around the same time on September 22, 1862, Lincoln signed the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. He stipulated in this order that if the Southern states refused to return to the Union, it would go into effect January 1, 1863. The South continued their rebellion and the proclamation was implemented. Part of this Proclamation allowed the US government to use former slaves as soldiers, stating “that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.” On January 31, 1863, the group training at Camp Saxton in Beaufort became the first official black regiment⎯the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry.1

The regiment was under the command of Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson, an abolitionist who helped finance John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The regiment was composed of freed slaves recruited from local plantations. Col. Higginson wrote about this unit in one of the most famous books on black military service, Army Life in a Black Regiment. He recorded that when he arrived to take command of the regiment, he found most of the soldiers to be illiterate runaway slaves. Nevertheless, the regiment participated in a number of important military operations. Higginson led the unit on an expedition up St. Mary’s River along the Georgia/Florida line from January 23 to February 1, 1863. The regiment helped capture Jacksonville, Florida on March 10, 1863.2

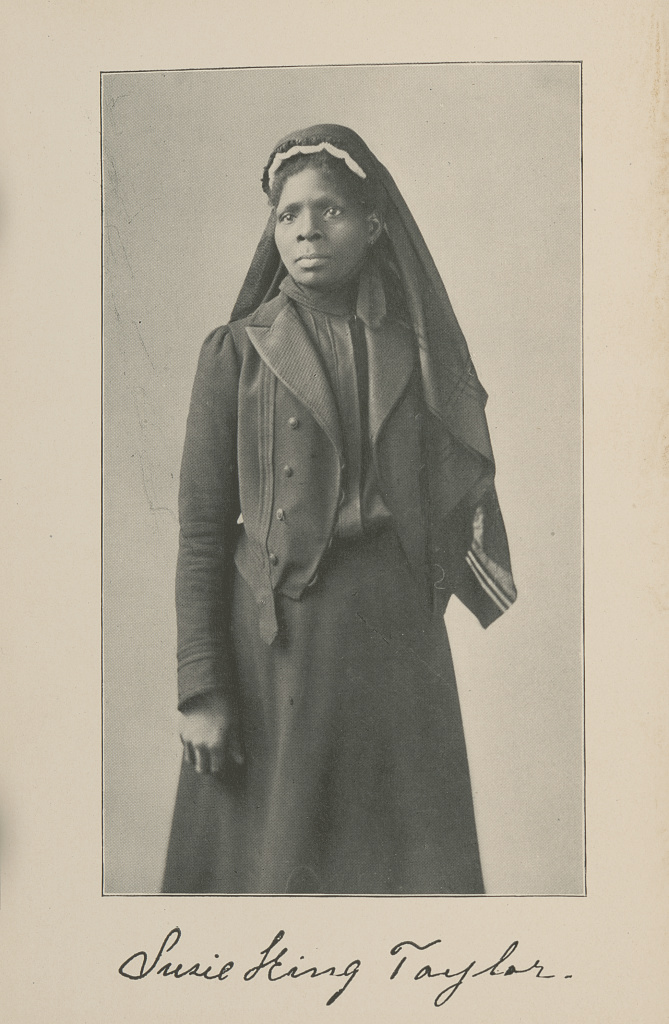

On February 8, 1864, the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry was designated as a federal volunteer unit⎯ the Thirty-third United States Colored Infantry (USCI). The regiment went on to participate in the capture of the Battery Gregg on James Island. Alongside two other Union regiments, they attacked the fort on July 2, 1864 and captured it within a day. In December 1864, they took part in the Battle of Honey Hill. Led by Major General John P. Hatch, the campaign’s goal was to cut off Confederate troops from the Charleston and Savannah Railroad. While completing this mission, a Confederate unit under the command of Colonel Charles J. Colcock met them on Honey Hill. Fighting to a stalemate, Hatch retreated to Boyd’s Neck. The Union troops suffered heavy casualties. During its last year of service, the regiment was part of the garrison of Savannah and Charleston. Susie King Taylor nursed and taught members of this unit to read. She wrote in her memoirs Reminiscences of my Life in Camp with the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops that the men sometimes came into contact with bushwhackers. These insurgents hid in bushes and shot Union soldiers or slashed their throats as they slept. King notes that many of these men’s lives were taken until a bushwhacker was caught, court-martialed, and hung at Wall Hallow, South Carolina. After this incident, the regiment remained unmolested until the end of the war. The unit was mustered out on January 31, 1866 and disbanded at Fort Wagner, South Carolina. 3

Endnotes

1 John T. Hubbell, “Abraham Lincoln and the Recruitment of Black Soldiers,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 2, no. 1 (1980): 6-21; Matthew Pinsker, “Emancipation Among Black Troops in South Carolina,” Emancipation Digital Classroom, accessed July 15, 2019, http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/emancipation/2012/11/06/emancipation-among-black-troops-in-south-carolina/; “Transcript of the Proclamation,” National Archives, accessed August 5, 2019, https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/emancipation-proclamation/transcript.html.

2 Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Army Life in a Black Regiment, (Boston, 1870), 1-5; “Guide to the 1st South Carolina / 33 Rd U.S. Colored Troops Records,” Online Archive of California, accessed July, 15, 2019, https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0d5n99qh/entire_text/.

3 “Guide to the 1st South Carolina,” Online Archive of California; “Battle of Honey Hill,” Town of Ridgeland South Carolina, accessed July 15, 2019, https://www.ridgelandsc.gov/battle-of-honey-hill; Susie King Taylor, A Black Woman’s Civil War Memoirs: Reminiscences of my Life in Camp with the 33rd United States Colored Troops Late 1st S.C. Volunteers,(Boston: Susie King Taylor, 1902), 43-44.

© 2019, University of Central Florida