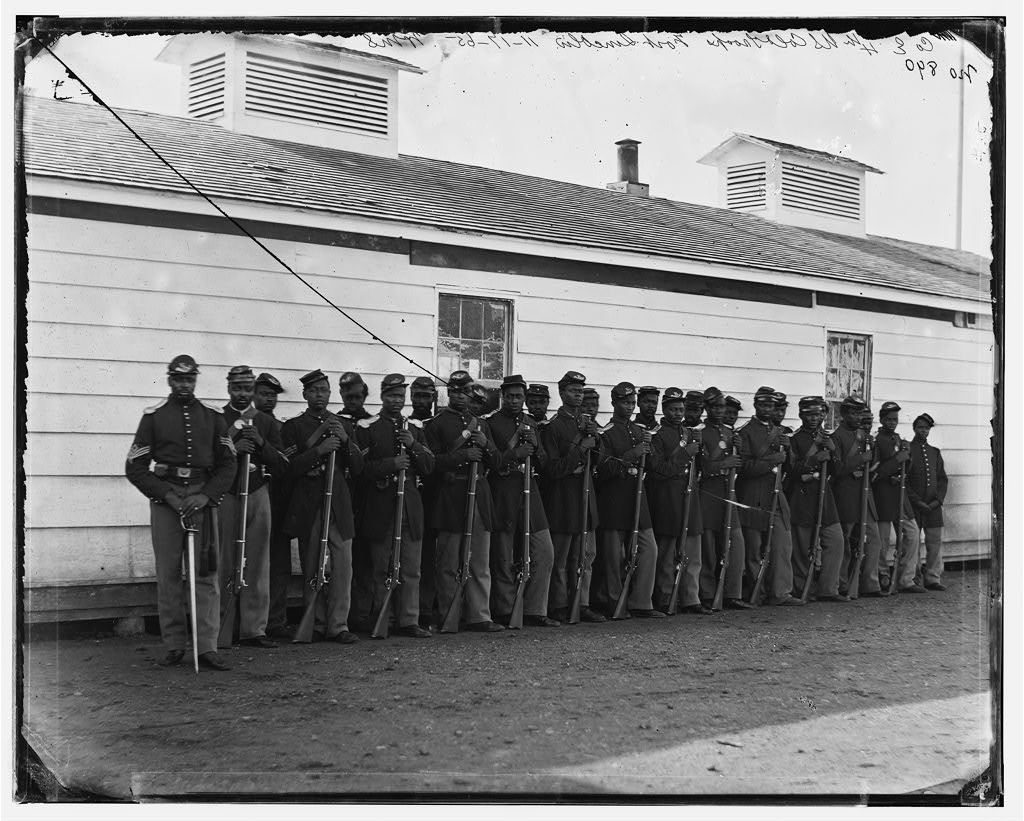

Civil War: African Americans in the Civil War

By Sara Nazarian

For much of the past century and a half, the contributions of African American soldiers to the Civil War were largely forgotten; their efforts were a footnote in our nation’s history. Americans realized only recently the important role that they played in this struggle. Yet despite this amnesia, black soldiers on the battlefield during the Civil War are important both to the war’s narrative and the narrative of our nation. Their involvement in the war ensured the end of slavery in the United States and the preservation of the Union.1

When war broke out between the United States and the Confederacy on April 12, 1861, both sides had not originally intended to enlist African Americans into the military. Northerners and Southerners agreed that they had no need for black troops. Southerners rejected using black Americans for the obvious reason that they were trying to preserve the institution of slavery. Northerners rejected black troops because the majority of white people in the North believed that the war was to preserve the Union, slavery and all. Both Confederates and Unionists believed that this war was a white man’s war. While Lincoln despised slavery, he needed the support of the white majority in the North to sustain the war effort so he eschewed emancipation as a war goal. Moreover, Lincoln knew that the loyal slave states of Maryland, Missouri, and particularly Kentucky, might secede if emancipation was a war aim. Under the Confiscation Act of 1861, Lincoln could have legally allowed blacks in the Union military, as laborers if not as soldiers. He chose not to invoke this part of the act because it suggested that the war threatened slavery.2

While white Northerners and Southerners refused to recognize emancipation as a war aim, enslaved men and women believed that they could use the war to free themselves. Slaves fled their masters for Union lines and forced U.S. officials to address slavery and slave owners. Southerners demanded that the Union Army help return their escaped slaves; however, the Confederacy used slaves for labor in military camps and fortifications, so Union soldiers were reluctant to return slaves to rebel owners. Even Unionists who accepted southern slavery before the war realized that Southerners used African Americans as part of the Confederate war effort prompting them to reassess black freedom and black enlistment.3

Other Northerners always believed that the war was about slavery. Some of these men and women began to agitate for black enlistment. Some military officials enlisted black Americans into the military without formal approval. During the second half of 1862, white Union military officials started forming regiments of black soldiers. In Kansas, James Lane formed the First Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry. Around the same time in South Carolina, David Hunter raised his own black regiment.4

After the Union experienced many military setbacks and grave losses in the Eastern Theater, many white Americans concluded that emancipation and the enlistment of black soldiers was the only way to save the Union. Five days after the “victory” at the Battle of Antietam, Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, an executive order that freed all slaves in rebel states on January 1, 1863. This order included a passage allowing the Union to enlist African Americans as soldiers. Approximately 180,000 served in the Union army and 18,000 served in the Union Navy between 1863 and 1865.5

Despite the important roles they played in the war, African Americans experienced harsh treatment as soldiers. Black soldiers were segregated into their own regiments commanded by white officers; many were relegated to non-combat positions, including building fortifications. These men initially received less pay. When black soldiers joined the Army in 1863, they made $10 a month, with $3 taken out for clothing; white soldiers made $13. Many black recruits did not receive the same bonuses that white soldiers received. Experienced black soldiers were not allowed to rise in the ranks to commissioned officer. It was not until June 15, 1864 that African American soldiers received equal pay. Black soldiers also faced far worse punishments than their white counterparts when captured by Confederate forces, including execution and re-enslavement.6

Regardless of their treatment, black soldiers performed well in battle. It was not about whether the battles were won or lost; it was about their so-called “fighting spirit.” White Americans in the North and South viewed black American as biologically inferior. While whites were considered more intelligent and “morally advanced,” blacks were thought to be less intelligent and “uncivilized.” As such, most white people thought that blacks would perform poorly as soldiers. White soldiers often observed and commented on black soldiers’ competence because of this race-based skepticism. In their early battles in the summer and spring of 1863 at Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana, Fort Wagner, South Carolina and Honey Springs, Oklahoma (Indian Territory) black soldiers demonstrated their bravery and courage to their white comrades.7

The critical year was 1864. Union morale was running low. General Ulysses S. Grant had taken command of the Union army and launched the Overland Campaign in the spring. Over the course of six weeks, the Union suffered heavy casualties. The election of 1864 was approaching and Lincoln needed some decisive victories in order to retain the presidency. Earlier, in February 1864, black troops fought a hard battle in Olustee, Florida. The Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Infantry, the Eighth United States Colored Infantry (USCI), and the Thirty-fifth USCI participated in this battle. The inexperienced Eighth broke ranks and fled under withering fire, but the Fifty-fourth held its formation and made sure the other regiments, black and white, escaped enemy fire. The Fifty-fourth had made the famous charge at Fort Wagner in 1863 immortalized in the movie “Glory” (1989). Black troops also took part in the Petersburg's campaign that eventually forced the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. At the end of the year, the Colored Troops played a critical role in the destruction of John Bell Hood’s Confederate Army of Tennessee at Nashville. Although some of these conflicts were considered failures⎯the Union lost the battle at Olustee and the Petersburg campaign failed to take the city for months⎯black troops were applauded for their efforts. Many white people began to believe that blacks were effective soldiers and acknowledged that their efforts helped turn the tide of the war in favor of the Union. By the end of 1864, the Union Army won a number of critical battles; Lincoln was elected for another term. His election ensured that the war would continue until Union victory.8

The emancipation of African Americans had various effects. Some black soldiers were awarded for their valor in battle. Many stayed in the military. Four African American regiments continued to serve in the Army after the Civil War: the Twenty-fourth and Twenty-fifth Infantry and the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry. Known as the Buffalo Soldiers, these units served in the Spanish-American War and the Philippine-American War. Most Civil War veterans returned to work as laborers or farmers, tending to land they owned or leased from others. Black men that were unable to work due to wartime disease and/or injury received pensions. Despite racism and the many challenges of the post-Civil War era, slavery ceased to exist because of the suffering and sacrifice of those who had been held in bondage.9

Despite these contributions, by the beginning of the twentieth century, most people forgot about African Americans in the Civil War. Only recently have historian’s amassed significant information on the history of black soldiers in the Civil War. Our hope is that historians continue to research African Americans’ contributions to the Civil War in order to acquire a more well-rounded and factual view of the war and its legacy.

Endnotes

1 Barbara A. Gannon, “African American Soldiers,” Essential Civil War Curriculum, accessed July 23, 2019, https://www.essentialcivilwarcurriculum.com/african-american-soldiers.html.

2 Gannon, “African American Soldiers”; John T. Hubbell, “Abraham Lincoln and the Recruitment of Black Soldiers,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 2, no. 1 (1980): 6-21.

3 Gannon, “African American Soldiers.”

4 Gannon, “African American Soldiers.”; Matthew Pinsker, “Emancipation Among Black Troops in South Carolina,” Emancipation Digital Classroom, November 06, 2012, accessed July 29, 2019, http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/emancipation/2012/11/06/emancipation-among-black-troops-in-south-carolina.

5 Gannon, “African American Soldiers.”

6 African American Soldiers During the Civil War,” Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861-1877, Library of Congress, accessed July 29, 2019, http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presentations/timeline/civilwar/aasoldrs; “Historical Context: Black Soldiers in the Civil War,” History Now, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, accessed July 29, 2019, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/content/historical-context-black-soldiers-civil-war; “Black Soldiers in the U.S. Military During the Civil War,” Educator Resources, National Archives, accessed July 29, 2019, https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/blacks-civil-war.

7 Lynching in America, (Montgomery, Alabama: Equal Justice Initiative, 2017), 8; Gannon, “African American Soldiers.”

8 Gannon, “African American Soldiers.”

9 Gannon, “African American Soldiers.”

© 2019, University of Central Florida