Bert Davison (July 25, 1892–February 26, 1945)

By Ashley Alligood

Early Life

Bert Collier Davison was born on July 25, 1892 in Atlanta, GA, to Anna Davison and Robert Davison, both Georgia natives. His siblings included Roy Davison (1888), Nellie Davison (1893), and Will Davison (1894). Robert worked as a carpenter in Atlanta while Anna raised her family at home. Bert received a grammar school education.1 In the mid-1890s, the family moved to Florida and settled in St. Petersburg.2 By 1910, at the age of 19, Davison worked as a pharmaceutical salesman at Budd’s Pharmacy in St. Petersburg.3

Military Service

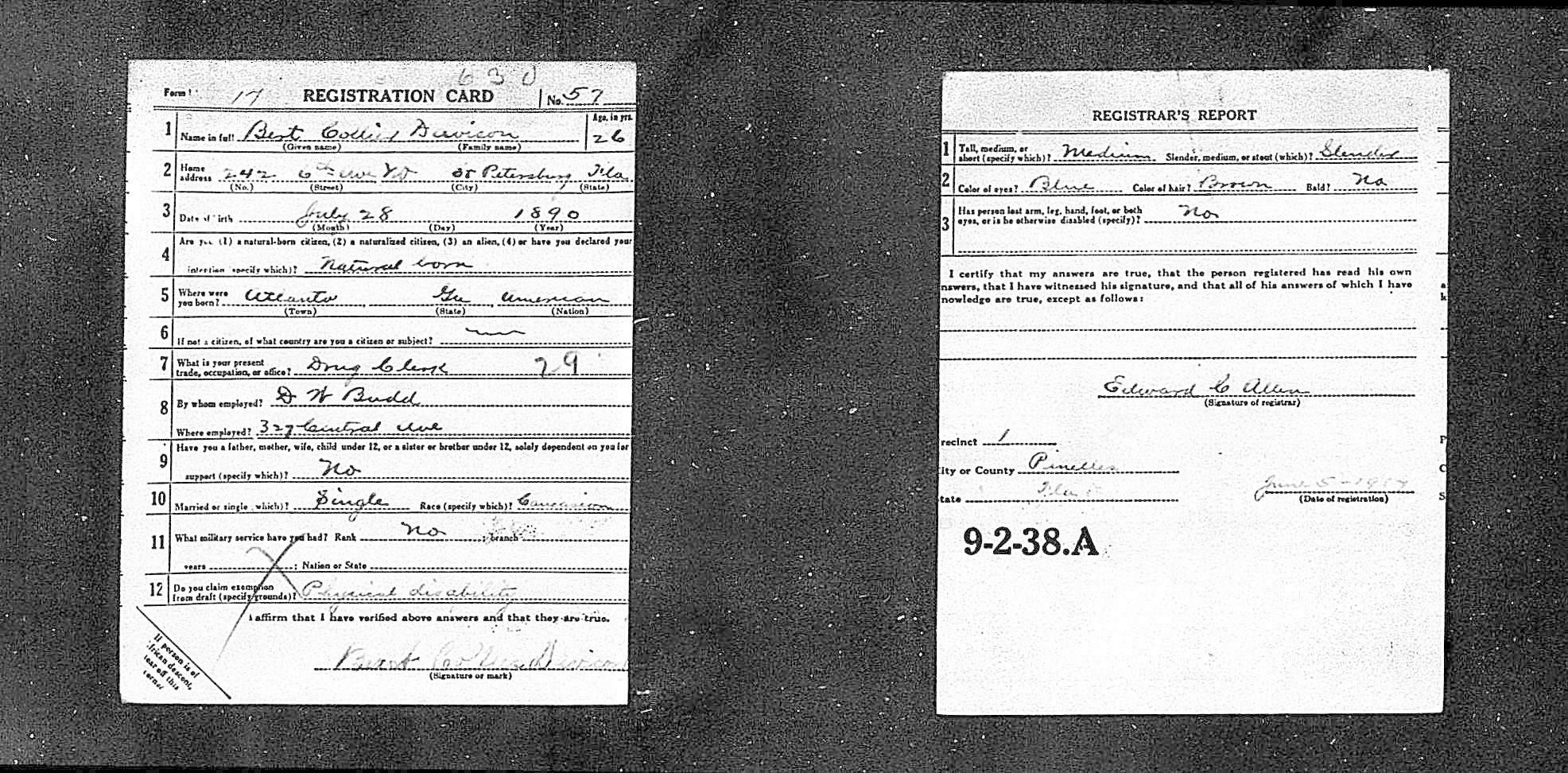

Davison registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, shortly after the US entered the war in April 1917. According to his registration card, pictured here, Davison claimed a physical disability, yet the Army must have believed it was not serious enough to excuse him from service. He was inducted into the Army in Philadelphia, PA, on June 26, 1918 as a private.4 He trained in Pennsylvania until September 8 when he left for France from Newport News, VA on the USS Zeelandia, a passenger and cargo steamship which the Navy commissioned for troop transport in 1918.5 Davison joined the Administrative Labor Army Service Corps of the Quartermaster Corps. The Quartermaster Corps handled logistics and the transport of supplies; Davison’s responsibilities, as part of the Administrative Corps, could have included the management of Army resources such as food and weapons, record keeping, supervising mail, or preparing divisional instructions.6 He likely worked in the Quartermaster Corps Headquarters, located in Chaumont, France.7 Davison continued to excel in his position through to the end of the fighting, as he earned a promotion to Corporal on October 1, 1918 during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.8

After the armistice on November 11, 1918, Britain, France, Belgium, and the US occupied the Rhineland, the western area of Germany and the left bank of the Rhine River. Having the Allied counties occupy the Rhineland helped to ensure that Germany would not take up arms and fight again. The US Third Army began its advance to occupy Koblenz, Germany on November 17, 1918. The administrative staff of the Army’s General Headquarters, the Third Army’s headquarters, and the Quartermaster Corps coordinated and supplied the nearly 240,000 soldiers during both their month’s long march over more than one hundred miles through parts of France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, as well as the eight-month long occupation of Germany’s Rhineland.9 The Allied-occupied territory ran along the Rhine River, from British-occupied Cologne in the north to French-occupied Mainz in the south. Centered around its hold on Koblenz, the US Third Army occupied the zone between its allies, an area of about 2,500 square miles.10 While occupying Koblenz, the military administrators set to work in helping to rebuild certain elements in the occupied zone, such as overseeing construction and street cleaning, mending streetcar and electricity issues, and rebuilding railways damaged in the war.11 The US Army also witnessed the deprivations the German people faced during the war. hardships such as long after the fighting had stopped.12 The Allied blockade of Germany (1914-1919), had, by war’s end, created extreme food shortages, which continued until after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. In the final years of the war, the situation for women, children, the elderly, and wounded Veterans deteriorated significantly. Women waited in long food lines and often had nothing to feed their families. In some cases, women led protests, demanding the government provide necessities.13

Due to the occupation of the Rhineland, Davison and his comrades stayed in Europe long after the fighting had stopped. Most American soldiers in Europe returned to the US within a few months of the armistice, yet those in administrative and supply roles were typically among the last to leave.14 A significant portion of the Service of Supply to stay on were African Americans. The US Army tasked them with rebuilding projects in France and Germany, and with burying and reburying the dead, and allowed many white soldiers to rest or travel back to the US.15 Davison was not among those that rested before returning home. The work he did administering the occupation earned Davison a promotion to Sergeant on May 20, 1919.16 Davison left from Brest, France on October 19, 1919 and arrived in Hoboken, NJ on October 28, 1919. He was honorably discharged on November 5, 1919.17

Post-Service Life

After returning home, Davison continued his work at Budd’s Pharmacy in St. Petersburg, FL. He used his experience to open his own pharmacy, in 1926, with Frank Kirkland, a pharmacist. Kirkland handled the pharmaceuticals while Davison focused on management and sales.18 On April 3 of the same year, Davison married Johanna Horstmann.19 Horstmann was born on January 27, 1897 in Bremen, Germany and arrived in New York, NY on November 3, 1923 on the SS Stavangerfjord.20 Horstmann likely experienced the hardships of the home front during the war, including the near starvation conditions.21 Germany also experienced substantial inflation that began at the start of the war in 1914 and continued through to 1924. After the war, and peaking in December 1923, hyper-inflation meant that the exchange rate for one US dollar was 4.2 trillion German Marks.22 This economic crisis may have been the reason Horstmann migrated from German to US in 1923.

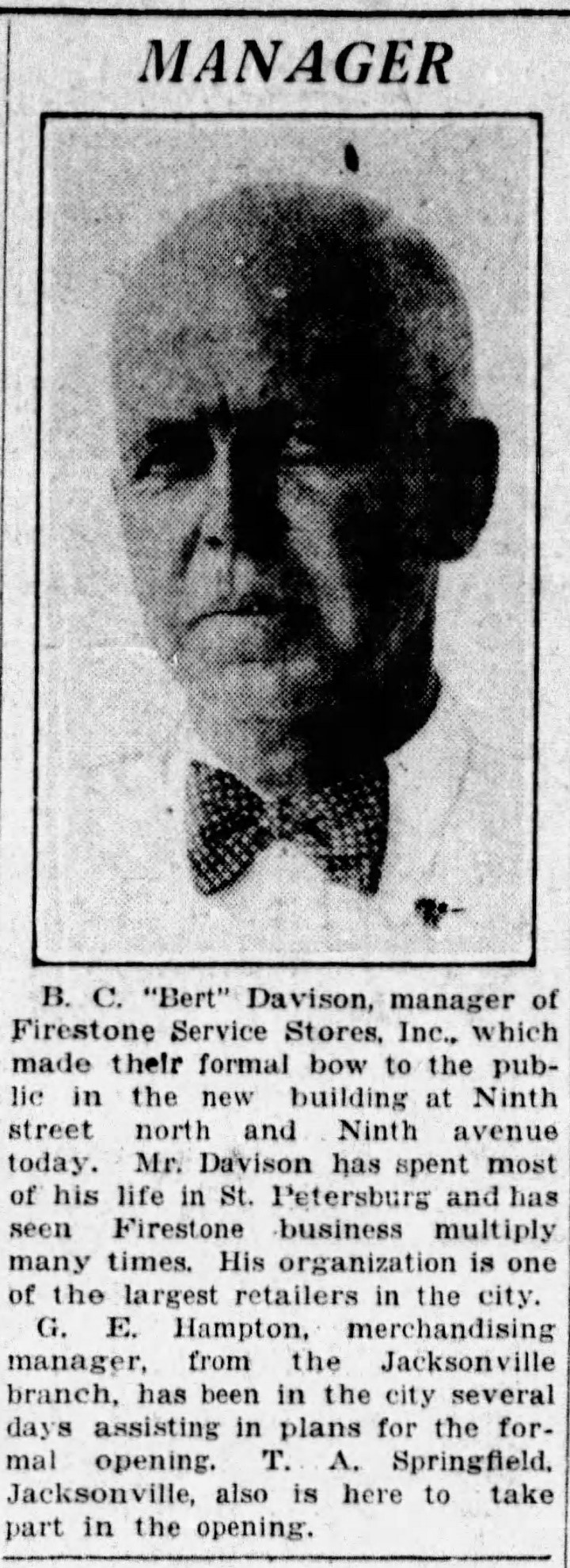

Just a few years after marrying Horstmann, Davison shifted occupations. As we can see from this news article, he became the manager of a Firestone tire store and filling station in August 1929, just a month before the stock market crash that precipitated the Great Depression.23 In 1930, Davison moved from Firestone to Goodrich, another national tire chain. He may have switched when, in the 1930s, Firestone experienced a recall. As a result, many stores began substituting Firestone tires for Goodrich tires.24 Moreover, he accomplished an incredible feat in the middle of the Great Depression. Davison opened his own tire store and filling station while remaining manager of the Firestone store, when most men had trouble finding any work.25 While automobile sales declined nationwide during this time, gasoline and tire sales continued, allowing Davison to expand.26

He accomplished all this despite health problems. While we do not have details about Davison ailments, he had major surgery at the Mound Park Hospital in St. Petersburg in July 1930 followed by six weeks of recovery.27 Once he was well, Davison continued his career in the automobile business until health problems forced him to retire early in 1940, at age forty-seven.28 Davison died at age fifty-two on February 26, 1945 after what his wife called a “long illness,” when she placed a “card of thanks” in the St. Petersburg Times.29 He was survived by his wife, and his brothers, Roy and Will. Davison is buried at Bay Pines National Cemetery in St. Petersburg, Florida section 10 row 1 site 15.30

Endnotes

1 “Florida, State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry.com, (accessed February 5, 2019). Entry for Bert Davison, St. Petersburg, Pinellas County, Precinct 3, Florida. p. 7.

2 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com, (accessed February 5, 2019), entry for Bert Davison, Hillsborough County, Florida; “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com, (accessed February 5, 2019), entry for Bert Davison, Pinellas County, Florida.

3 “1910 United States Federal Census”; “WWI Draft Registration Cards,” database, Fold3.com, (accessed February 13, 2019), entry for Bert Collier Davison.

4 “WWI Draft Registration Cards”; “WWI Service Cards,” database, FloridaMemory.com, (accessed January 20, 2019), entry for Bert C. Davison.

5 "Zeelandia (Id. No. 2507)," Naval History and Heritage Command, December 14, 2015, (accessed March 13, 2019), https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/z/zeelandia.html; “US Army WWI Transport Service, Passenger Lists,” database, Fold3.com, (accessed February 13, 2019), Outgoing, Zeelandia, 1918 Jun 30 - 1919 Nov 12, p. 549, entry for Bert Collier Davison.

6 “U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963,” database, Ancestry.com, (accessed February 5, 2019), entry for Bert Davison; Jennifer Keene, World War I: The American Solider Experience (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 150-152; Henry Sharpe, The Quartermaster Corps in the Year 1917 in the World War (New York: The Century Company, 1921), 284.

7 TOrder of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War. Vol. 1, American Expeditionary Forces: General Headquarters Armies, Army Corps, Services of Supply Separate Forces , official government ed., (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1988), 11-12.

8 “WWI Service Cards.”

9 United States Army, The United States in the World War, 1917-1919: American Occupation of Germany (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1991), Vol. 11: 79, 143-144; Scott Walker, "The U.S. Third Army and the Advance to Koblenz, 7 November - 17 December 1918." Army History, no. 32 (1994): 28, 32; Paul Herbert, "Watch on the Rhine: The 1st Division in the Occupation of Germany, 1918-1919," On Point 15, no. 2 (2009): 35-36.

10 Walker, "The U.S. Third Army and the Advance to Koblenz, 7 November-17 December 1918," 28-29; Alfred Cornebise, "Der Rhein Entlang: The American Occupation Forces in Germany, 1918-1923, A Photo Essay," Military Affairs 46, no. 4 (1982): 184.

11 Alexander Barnes, “‘Representative of a Victorious People’: The Doughboy Watch on the Rhine," Army History, no. 77 (2010): 7, 11-12.

12 Belinda J. Davis, “Homefront: Food, Politics and Women’s Everyday Life during the First World War,” in Home/Front: The Military, War and Gender in Twentieth-Century Germany, eds. Karen Hagemann and Stefanie Schüler-Springorum (Oxford: Berg, 2002), 128-131.

13 Belinda J. Davis, “Homefront,” 125-127.

14 Barnes, “‘Representative of a Victorious People’: The Doughboy Watch on the Rhine," 15-16.

15 John C. Sparrow, History of Personnel Demobilization in the United States Army (Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army, 1952), 11-19; Edward M. Coffman, The War to End all Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968), 358.

16 “WWI Service Cards.”

17 “US Army WWI Transport Service, Passenger Lists,” database, Fold3.com, (accessed February 13, 2019), Incoming, America, 28 Oct 1919 - 8 Feb 1923, p. 165, entry for Bert Collier Davison.

18 “1920 United States Federal Census;” “Firestone’s New Home Is Nearly Ready,” St. Petersburg Times, June 30, 1929, p. 8, database, Newspapers.com; “New Drug Store Opened in City,” St. Petersburg Times, August 21, 1924, p. 12, database, Newspapers.com.

19 “Florida, County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry.com, (accessed February 5, 2019), entry for Bert C. Davison and Johanna Fredericke Davison.

20 “Florida, Naturalization Records, 1847-1995,” database, Ancestry.com, (accessed February 5, 2019), entry for Johanna Fredericke Davison.

21 Belinda J. Davis, “Homefront,” 128-131.

22 Bernd Widdig, Culture and Inflation in Weimar Germany,” (Berkley: University of California Press, 2001), 36-40.

23 Robert Samuelson, "Revisiting the Great Depression," The Wilson Quarterly 36, no. 1 (2012): 38-39.

24 “Manager,” St. Petersburg Times, August 31, 1929, p. 10, database, Newspapers.com; “More Than Million Dollars In Building Is Under Way Despite Summer Slump,” St. Petersburg Times, August 18, 1929, p. 8, database, Newspapers.com; “Firestone’s New Home Is Nearly Ready,” St. Petersburg Times, p. 8; Chris Collins, “Dealers deluged, but replacements scarce,” Tire Business, 2000.

25 “Opens Store,” St. Petersburg Times, December 28, 1930, p. 7, database, Newspapers.com.

26 Glenn Carroll and Claude Fischer, "Telephone and Automobile Diffusion in the United States, 1902-1937," American Journal of Sociology 93, no. 5 (1988): 1154.

27 “Florida Air Far Best For Tires,” St. Petersburg Times, August 24, 1930, p. 5, database, Newspapers.com; “Personal Mention,” St. Petersburg Times July 31, 1930, p. 6, database, Newspapers.com.

28 “Bert C. Davison, Retired Business Man Here, Dies,” St. Petersburg Times, February 27, 1945, p. 2, database, Newspapers.com; “United States Census, 1940,” database, FamilySearch.org, (accessed March 3, 2019) entry for Bert Davison, Saint Petersburg, Pinellas County, Florida.

29 “Card of Thanks,” St. Petersburg Times, March 2, 1945, p. 2, database, Newspapers.com.

30 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, “Davison, Bert C,” in “Grave Locator,” VA, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, n.d., accessed February 5, 2019, https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/.

© 2019, University of Central Florida