Estevan Reana Rojo (August 16, 1898–April 25,1961)

By Jelisa Sanchez and Walter Napier III

Early Life

Estevan Reana Rojo was born in Tampa, FL, on August 16, 1898.1 His parents Esteban Rojo and Maria Reana came from Santander, Spain and Sagua La Grande, Cuba, respectively.2 Esteban migrated to Cuba where he met and married Maria.3 Estevan was the youngest of their eight children: Rufina (1881), Joaquin (1885), Eloisa (1887), Candida (1889), Antonio (1890), Alberto (1892) and, Jacinta (1894).4

Esteban arrived in Cuba during a rocky period in the island nation’s history. At the start of what became known as the Ten Years War (1868-1878), wealthy planters demanded independence from Spain. Although the Ten Years War did not bring independence, it did inspire a desire for Cuban independence among the Cuban people. During the Cuban War of Independence (1895-1898), including what became known in the US as the Spanish American War (1898), Cubans finally gained their independence from Spain.5

Throughout this tumultuous period, Esteban, along with a growing number of Cubans, immigrated to the US.6 After arriving in 1882, Esteban became a wrapper selector for the expanding Florida cigar industry, first in Key West and later in Tampa.7 Founded in 1869 by Vicente Martinez Ybor, Ybor left Cuba and decided to move his cigar business to Key West.8 The business employed a growing number of Cuban immigrants in the US, and provided crucial support for the independence movement taking place in Cuba.9 While we do not know if Esteban provided support to the independence movement, his work in Florida supported his growing family in Cuba. By 1887, the Rojo family had all moved to Florida, and the family grew with the birth of Eloisa, the family’s first US born child.10 By 1888, Esteban worked as a “wrapper selector” in Key West, a position that required him to travel to various farms and plantations to select the best tobacco leaves to make cigars.11 By 1900, Esteban had moved to Tampa, consistent with the transition of the industry from Key West to Tampa, and had maintained his role as a wrapper selector.12 Unfortunately, Esteban died in 1905, when Estevan was only seven years old.13 It appears that the family worked together to get through Esteban’s passing. By 1910, sister Eloisa had married Manuel Martinez, another cigar industry worker, and younger brother Antonio lived with them.14 While the census does not list Estevan as living in his sister’s home in 1910, in 1920, he lived with Manuel and Eloisa after returning from France.15

Military Service

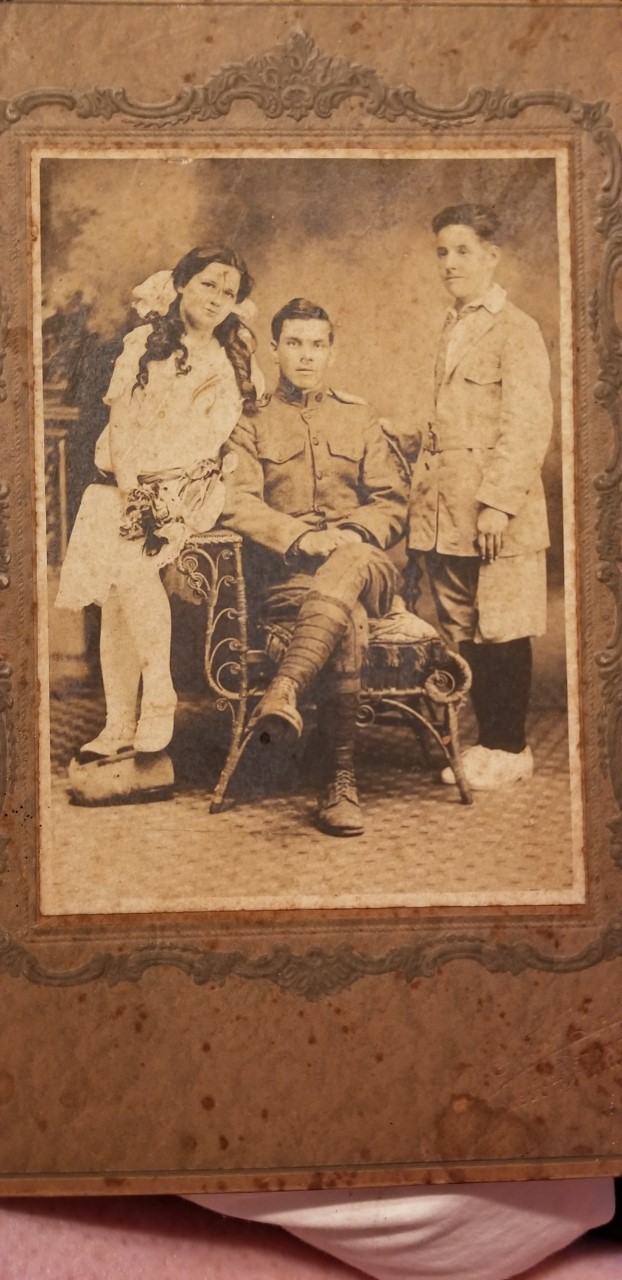

On June 23, 1916, Estevan joined the Florida National Guard at eighteen years of age.16 Estevan, seen here in uniform, was assigned to the 124th Infantry as a wagoner. Wagoners took care of pack animals and the movement of guns, ammunition, and supplies. Despite the early developments of aircraft and automobiles, horses and mules transported the majority of military supplies well into the twentieth century.17

The Army drafted the 124th into federal service on August 05, 1916 in support of the Mexican Border War.18 Estevan, along with 100,000 National Guard soldiers from around the US, served along the Texas-Mexico border, preparing for combat.19 By 1917, the situation on the border had cooled down, and the activated guard units received orders to return home. The 124th officially mustered out of service in March 1917.20

One month later, the US declared war on the Central Powers, joining World War I. While waiting to see what role he and his comrades might play in the war, Estevan was promoted to private on May 20, 1918.21 In June, Estevan attached to 163rd Infantry and deployed to France. Shortly after his arrival, he transferred again to the 119th Field Artillery (FA).22 The 119th FA was designated to support the 32nd Division at Chateau-Thierry.23

During World War I, even though automobiles made an appearance, horses and mules still moved the majority of military supplies and equipment.24 Men like Rojo, wagoners, cared for the various pack animals in military use. These men fed and groomed their animals, harnessed and unharnessed them each day. They ensured wellbeing of the horse or mule; they understood that the care of the animals supersede that of the men taking care of them.25 If a gas attack occurred, for example, the soldiers used their own masks to save the horses.26 The men knew how hard it would be to replace an animal they needed to supply the war. Over four years, approximately eight million horses and mules died in the violence of mechanized warfare.27 Around 1.3 million horses came from the United States, but only 200 returned.28 In one instance, due to the constant shortage of animals, the men of the 119th had to drag sixteen caissons laden with munitions for five days in order to supply the battle at Chateau-Thierry.29

The fighting around Chateau-Thierry lasted through the end of July. The 119th remained in constant contact with the enemy the whole month. In August, the 119th provided artillery support for both the 32nd and 28th Divisions as the US Army, along with its Allies, sought to push back the German lines throughout the summer of 1918. At the end of August, the 119th again provided artillery support to the 32nd Division north of Soissons, as the division fought to recapture territory lost to the Germans during the Spring Offensive of 1918.30

After some rest in September, Estevan and the 119th marched seven muddy nights to reach the front line and prepare for the largest land battle in US military history, the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. The artillery began barraging the German positions on the morning of September 26th, with the 119th supporting the 79th Division in the opening hours of the conflict. Despite delays and heavy resistance, the 79th pushed forward and reached positions near Montfaucon, the 79th’s initial objective. The 79th had to fight an additional day to capture the point due to the stubborn German defense. Estevan remained in the area until October, when the 119th returned to the 32nd Division, which in short order captured four strategic positions. In November, during the final eleven days of the war, the 119th supported the 79th Division, taking part in a twenty-five-kilometer-long, eleven-kilometer-deep artillery barrage along the northern edge of Bois de Bantheville, five kilometers from what is now the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery.31

Estevan had been in near constant combat since his arrival in France. In total, the 119th supported eleven different infantry divisions, and assisted in the recovery of over forty-three miles of French territory.32 Despite the armistice, the war did not end on November 11 for most of those who fought, or the civilian populations of Europe and their empires. The war destroyed infrastructures, including transportation networks and ravaged communities. The logistics of demobilization meant that millions of US troops sat around for months, often bored, hungry, and homesick.33 The 119th set up camp in Mauvages, France, where on February 2, 1919, the local community celebrated a Catholic mass honoring them.34 On May 3, 1919, the regiment returned to the US on the USS Frederick.35 Finally, on May 21, 1919, after service on the Mexican border and in France, Estevan was discharged from the Army and returned home.36

Post-War Life

When Estevan returned from France, he lived in Tampa with his sister Eloisa, and her husband, Manuel Martinez. Only twenty-one years old, Estevan worked as a salesman in a grocery store, while his sister and brother-in-law worked in the cigar factory.37 Estevan applied for a US passport and went to Cuba in October 1920 to visit relatives for a six-month period.38 On February 16, 1922, Estevan married Maria C. Cabello.39 Unfortunately, in 1930, Maria faced complications in childbirth, causing the death of both mother and child.40

After his tragedy, Estevan began to rebuild his life when he married Anna Mandala, creating a new family that included her son Steve.41 To support his family, Estevan worked as a builder and a painter throughout his life, as we see here.42 Estevan Rojo passed away on April 25, 1961, at the age of 62 at Bay Pines Veteran Hospital 103 days after admission.43 His family believes his death was the result of complications from exposure to mustard gas during the war.44 Estevan now rests at Bay Pines National Cemetery, Section 36, Row 3, Site 9.

Endnotes

1 "U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963, database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed April 28, 2018) Entry for Estevan Reana Rojo; “U.S Passport Applications 1795-1925” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed April 28, 2019) Entry for Estevan Reana Rojo.

2 Katrina Bigham (a member of the Rojo family), Amelia Lyons and Jelisa Sanchez, e-mail correspondence, April 2019; “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed April 28, 2019) Entry for Estevan Reana Rojo. Esteban, the elder, is most often listed as Esteban in the documents. While the younger Estevan is sometimes listed in the sources as Esteban (as in his passport application) or Estevan (as in the 1920 Census), the bio uses Esteban in relation to the father, and Estevan in relation to the son, for clarity. We would like to thank Katrina Bingham and the Rojo family for speaking with us, and for giving us permission to include family photographs in our biography.

3 1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed April 28, 2019) Entry for Estevan Reana Rojo.

4 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com.

5 Gary R. Mormino "Tampa's Splendid Little War: Local History and the Cuban War of Independence." OAH Magazine of History 12, no. 3 (1998): 37-42. 38-39. For more information on the Spanish American War see G. J. A. O’Toole, The Spanish American War: An American Epic 1898. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1986.

6 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com.

7 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com.

8 De La Cova, “Cuban Exiles in Key West,” 293.

9 Louis A. Pérez “Reminiscences of a Lector: Cuban Cigar Workers in Tampa." The Florida Historical Quarterly 53, no. 4 (1975): 443-49. 443.

10 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com.

11 “Bensel’s Directory of the City and Island of Key West 1888,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed August 10, 2019) Entry for Estevan Rojo. “Florida, Passenger Lists, 1898-1963,” database Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed August 10, 2019). Entry for Estevan Rojo.

12 “1900 United States Federal Census”, database, Ancestry.com.

13 “U.S Passport Applications 1795-1925” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed April 28, 2018) Entry for Estevan Reana Rojo.

14 1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed October 24, 2019) Entry for Eloisa Martinez (also under Elviza Martinez).

15 1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed October 24, 2019) Entry for Estevan Rojo. Further evidence for the family dispersing among the older children’s families is that Alberto’s World War I draft card lists his elder sister Rufina as his next of kin. “U.S., WWI Civilian Draft Registrations, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed October 24, 2019) Entry for Alberto Rojo.

16 “WWI Service Cards,” database, FloridaMemory.com, (https://www.floridamemory.com/FMP/wwi/cards/1204/13/026148-1204-13-DOC000353-P01.jpg: accessed August 01, 2019) Entry for Estevan Rojo.

17 Richard S. Faulkner, Pershing’s Crusaders: The American Soldier in World War I (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2017). 360.

18 “124th Infantry Regiment (First Florida) Lineage and Honors,” history.army.mil (https://history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/lineages/branches/inf/0124in.htm: accessed August 05, 2019).

19 “1916-The Mexican Border Campaign,” history.army.mil (https://history.army.mil/news/2015/150200a_mexicanWar.html: accessed August 05, 2019).

20 “124th Infantry Regiment,” history.army.mil.

21 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Estevan Rojo.

22 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Estevan Rojo.

23 Chester B. McCormick, “119th Field Artillery in World War I,” Michigan.gov, Michigan department of Military and Veteran Affairs, (https://www.michigan.gov/dmva/0,4569,7-126-2360_3003_3009-17205--,00.html: accessed April 29, 2019).

24The United States World War One Centennial Commission, “Horse Heroes site honors the 1,325,000 American horses & mules that served in WWI,” worldwar1centennial.org (https://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/communicate/press-media/wwi-centennial-news/5546-horse-heroes-website-honors-the-1-325-000-american-horses-and-mules-who-served-in-ww1.html: accessed October 19, 2019).

25The United States World War One Centennial Commission, “Horse Heroes: Care and Feeding.” worldwar1centennial.org (https://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/care-and-feeding.html: accessed October 19, 2019).

26 The United States World War One Centennial Commission, “The Veterinary Corps: Caring and Curing.” worldwar1centennial.org (https://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/brookeusa-veterinary-corps.html: accessed October 19, 2019).

27 “Horse Heroes site honors the 1,325,000 American horses & mules that served in WWI,” worldwar1centennial.org.

28 “Horse Heroes site honors the 1,325,000 American horses & mules that served in WWI,” worldwar1centennial.org.

29 McCormick, “119th Field Artillery in World War I,” Michigan.gov.

30 McCormick, “119th Field Artillery in World War I,” Michigan.gov.

31 McCormick, “119th Field Artillery in World War I,” Michigan.gov. The cemetery is a part of the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC). It is the largest overseas American cemetery, and the final resting place of 14,246 military dead. See abmc.gov for more information on the cemetery, and other monuments memorializing World War I and other US conflicts.

32 McCormick, “119th Field Artillery in World War I,” Michigan.gov.

33 Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience. 182.

34 John DellaGiustina, An American Soldier in the Great War: The World War I Diary and Letters of Elmer O. Smith Private First Class, 119th Field Artillery Regiment, 32nd Division. Hellgatepress.com. (http://www.hellgatepress.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/24-pages-from-AmericanSoldierv_0.pdf: accessed August 1, 2019). xvi.

35 DellaGiustina, “An American soldier in the Great War”: xiv-xvi.

36 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Estevan Rojo.

37 “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com.

38 “U.S Passport Applications 1795-1925,” Ancestry.com, Estevan Reana Rojo.

39 “Florida Marriages, 1837-1974,” database, FamilySeach.org (http://www.familysearch.org: accessed April 29, 2018) Entry for Estevan Rojo and Maria Cabello, Hillsborough, Florida.

40 E-mail correspondence, April 11, 2018.

41 E-mail correspondence, April 11, 2018.

42 E-mail correspondence, April 11, 2018; “U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963” database ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com: accessed August 15) entry for Estevan Rojo.

43 “U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963” database Ancestry.com.

44 E-mail correspondence, April 11, 2018.

© 2019, University of Central Florida