Jefferson “Jeff” Howard (October 20, 1894–August 29, 1962)

By Jack Barberian and Gramond McPherson

Early Life

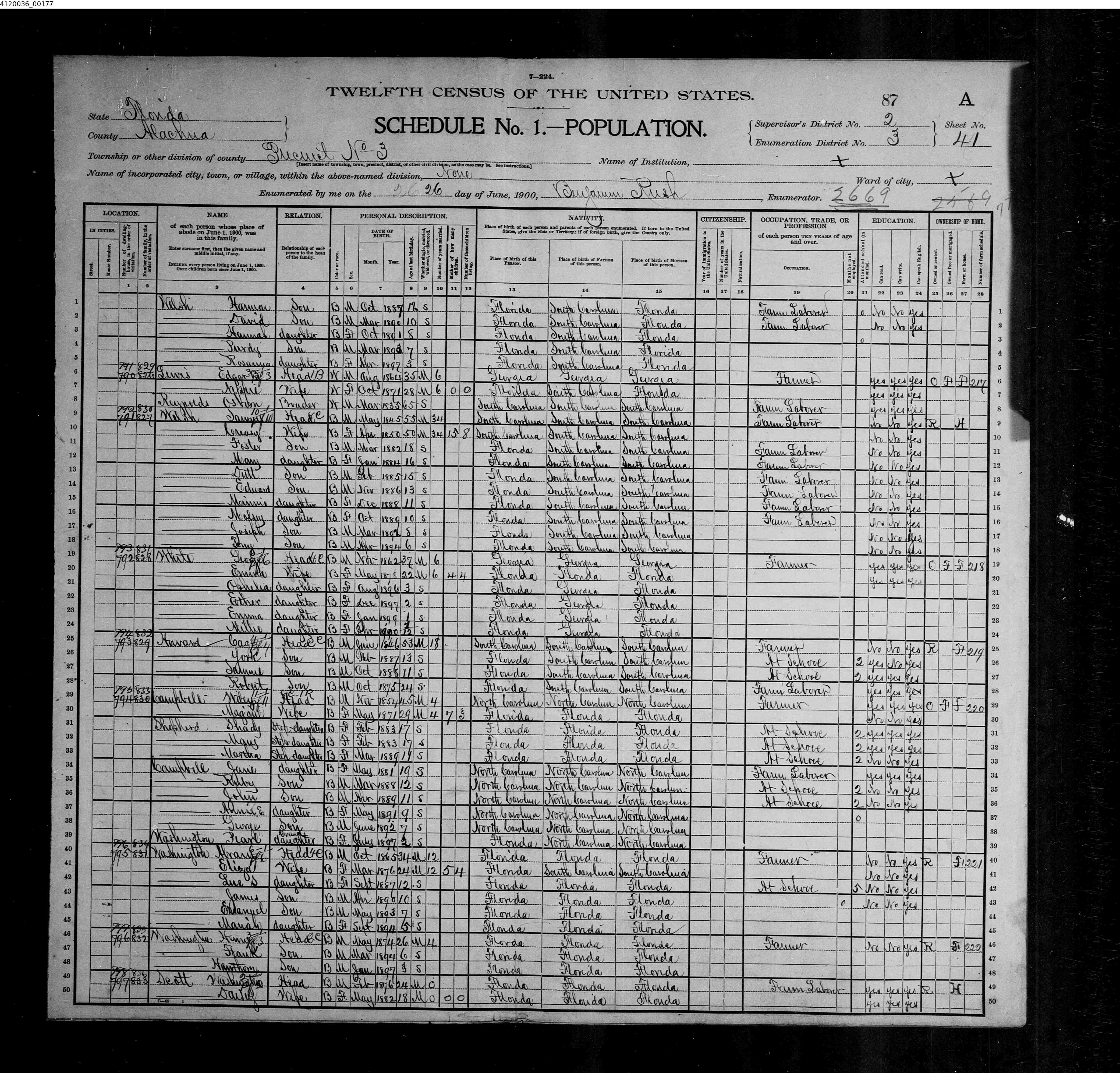

On October 20, 1894, Jefferson “Jeff” Howard was born to Cage and Rachael Howard in Alachua, FL.1 According to the 1900 Census, his mother Rachael gave birth to a total of eighteen children with ten surviving into the twentieth century. The census lists the family spread across two separate residences in Alachua, the first headed by Jeff’s father Cage (line 25) and three of his sons. Jeff (line 78) lived in the second residence with his older brother Maxey Anderson and Maxey’s wife Ella, as seen here. Maxey’s household also included the couple’s three young children, Jeff and Maxey’s mother Rachael and their three sisters and two brothers. Situated near one another, the two residences allowed the large family to remain close.2

Like a vast majority of black families in the rural South, Howard’s family worked on the farm. Most of these families worked as tenant farmers, sharecroppers and wage laborers for white planters and landlords, reflecting the difficulties blacks had in acquiring their own land after the Civil War due to poverty and white resistance. While renting land afforded black farmers greater autonomy, because they owned part of the crops they produced, compared to sharecropping and wage labor, these systems saw black families in a continuous cycle of debt to their landlords and store creditors with few achieving land ownership.3 The 1900 Census classified farmers as individuals who owned or rented a farm or operated a farm on behalf of the owner. As Jeff’s father Cage is listed as a farmer who rented his place of residence, he likely worked as a tenant farmer on land owned a white landlord. As the family’s livelihood depended on cultivating farm land and producing a plentiful harvest, Jeff’s mother Rachael, along with most of his older siblings, worked with Cage as farm laborers.4

By 1910, Howard, then fifteen years old, joined the family occupation by working as a farmhand while continuing to live with his brother Maxey and family in Alachua. Due to the demands of the farm, he only attended school up to the third grade.5 In the rural South, many black children received less education compared to their white counterparts as their parents or white employers often pulled them from school to labor on farms. For black children who did attend school, racial segregation restricted them to underfunded black schools with secondhand books and supplies, overcrowded classrooms and less qualified teachers. With fewer black public schools available, especially in rural areas, a large percentage of black children like Howard only received an elementary school education.6

By 1917, Howard, in his early twenties, lived in Clearwater in Pinellas County, FL, near Tampa. During this time, he worked as an itinerant laborer for the Southern Railway Company at a depot in the western North Carolina town of Marion.7 Compared to farming, the railroad industry provided secure employment through a variety of unskilled jobs such as laboring on railroad tracks to skilled positions like firemen (who fed coal into the engine’s boiler), and brakemen (who manually set hand brakes to stop train in cases of air brake failure).8 While working for the railroad required more physical and dangerous labor than farming, the weekly cash wages provided greater financial stability and more mobility for black laborers like Howard to support their families.9 Black railroad workers used their experiences during and after World War I to challenge race-based wage discrimination, abusive treatment by whites, and to demand equal rights.10

Military Service

After the US entry into World War I in April of 1917, Congress, on May 18, 1917, passed the Selective Service Act to increase the manpower of the US military through conscription. The first registration act, on June 5, 1917, required all men in the US between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-one to register. Over ten million men registered, including Howard at the age of twenty-three.11 At the time of his registration, he listed himself as a married man and sought an exemption in order to support his wife. Howard likely lived in a common-law marriage with Francis Davis prior to their legal marriage on January 16, 1918.12 Yet, while powerful white landowners in the South used their influence to gain exemptions for their black employees, those without such support saw their claims viewed unsympathetically by white-controlled Southern draft boards. These boards argued the military often improved the financial standing of blacks as the thirty-dollar monthly allowance a soldier earned would provide more income than most standard employment like sharecropping. Thus nationwide, the military drafted one-third of black registrants, compared to one-fourth of all white registrants.13

On July 1, 1918, Jeff and Francis welcomed their first son, Thomas Jefferson Howard in Clearwater.14 A few weeks later on July 18, the Army inducted Howard; he reported for duty at Camp Dix, NJ.15 Despite black soldiers’ willingness to serve in combat roles, white military officials sought to ensure the maintenance of a race-based power system. Black soldiers served in segregated units, and with rare exceptions, in noncombatant roles. Whites, particularly in the South, feared the consequences of arming and training African Americans with firearms, believing black soldiers would return home and initiate a race war. Thus, the War Department assigned most black troops like Howard to non-threatening roles within Quartermaster and Engineer units that required minimum training; most black soldiers supported the war effort by loading and unloading supplies, digging ditches, building roads, and serving as drivers and cooks.16

At Camp Dix, Howard joined the Company L of the 807th Pioneer Infantry which formed in July 1918 as one of sixteen black pioneer regiments which replaced white pioneer units slated for conversion into infantry regiments. On September 4, 1918, Howard and his regiment sailed from Hoboken, NJ aboard the USS Siboney to join the war effort in France.17 Of the various types of noncombatant black units, pioneer infantry units gained prestige as elite regiments. These units consisted of white officers commanding black soldiers along with white and black specialists such as mechanics, skilled horsemen, and carpenters. In serving overseas, black soldiers like Howard performed less-appealing tasks in constructing and repairing roads, bridges, and railroads as well as burial duty.18 Theoretically, black and white pioneer infantry units received standard infantry training to be used, if necessary, in combat. US military officials did not seriously contemplate using black units in this capacity, however, as their paled-down training emphasized their true function as laborers. Yet, as these black units served in technical roles on the front lines of combat, Howard and his fellow soldiers experienced direct action with the enemy.19

While many black soldiers felt slighted by having to perform these duties and faced humiliation, mistreatment, and outright brutality, the unheralded service of black soldiers like Howard greatly contributed to the overall war effort both in the US and overseas.20 Shortly after their arrival overseas, the US Army transferred command of the 807th regiment to the French Army. Herbert Young, a contemporary of Howard in the 807th, reflected in an interview decades later: “When I went to France, they put us with the French Army; the U.S. Army didn't want us because we were colored.''21 The French Army, in suffering heavy casualties, desperately appealed for fresh American forces to serve under French control. As Commanding General John Pershing had direct orders from President Woodrow Wilson to keep the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) under American control, Pershing satisfied both dilemmas in granting the French four black combat infantry units of the Ninety-Third Division.22 In addition, the US Army also allowed segregated non-combat black units to serve with the French Army.23 As a non-combat unit, the 807th likely provided technical support to a French combat unit.

In serving in exemplary fashion and with distinction during his time overseas with the 807th, Howard received a promotion to the rank of corporal.24 Along with the other men of the 807th, Howard experienced the brutality of war as the arrival of long-range artillery placed support troops in constant danger. Moreover, these troops often repaired trenches near the front where they faced enemy fire and poison gas. Gas often settled in low spaces, sitting dormant for periods before it was stirred up by rain, construction, or more artillery fire.25 Under the command of the French Army, the 807th took part in the Meuse Argonne Offensive between October 25 to November 11, 1918, the deadliest land battle in American history.26 Young, Howard’s contemporary, described the heat of the battle. In facing heavy German fire, while engaged in building bridges on the front line, he remembered, “a lot of our men died fighting” as Young and the other members of the 807th engaged the enemy with bayonets.27 The efforts of the 807th helped produce an Allied victory that led to the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918.

For their service in France, General Pershing, on April 19, 1919, awarded the 807th regiment the Silver Band to be engraved and placed upon the Pike of Colors of Lance of the Standard for their participation in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.28 After the war ended, Howard and the surviving members of the 807th remained in France, serving alongside the First Army Engineers performing construction work until mid-1919. Howard’s duties also likely included burying the dead, including burying members of his unit who succumbed to the influenza pandemic. On June 25, 1919, Howard and the surviving soldiers of Company L of the 807th left the port of Brest, France on board the USS Orizaba, returning to the US.29 After the war, W.E.B. DuBois, among the most prominent black leaders of his time, celebrated the regiment as a “compliment to our race.” DuBois detailed the pride of the black community towards some in the unit earning the French Croix de Guerre and highlighted the characteristics of “bravery and cheerfulness” assigned to the 807th for their performance of duty.30

Post-Service Life

After his discharge, Howard returned to Clearwater. By 1920, Jeff supported his wife Francis and young son Thomas as a grove worker.31 Soon, however, the family relocated to New Jersey where they welcomed their second son Theodore Roosevelt Howard on November 19, 1923 in the city of New Brunswick.32 While we are unclear why the family relocated, the Howard family likely followed the trend of black families leaving the rural South for the industrial North, which became associated with the First Great Migration. For many blacks, migration to the North brought the promise of steady and well-paid employment and the prospect of saving to purchase property.33 While we do not know how long they remained in New Jersey, the Howard family returned to Clearwater by 1930, likely due to the greater opportunities that existed, even at the start of the Great Depression, in Florida. Whether through saving up money while in New Jersey or through Howard’s employment as a grove laborer in Florida, by 1930, the family lived in their own purchased home.34 Pinellas County produced high volumes of citrus, ranking second among Florida’s counties in the 1926-1927 growing season.35 As a native Floridian, Jeff experienced the wave of white and black migrants to Florida seeking work in the citrus industry, which only increased as a result of the Great Depression. While white laborers found work in packing sheds, which offered higher wages and some legal protections, white employers generally hired black laborers to work in the fields where they received lower wages and no labor protections.36

In surviving the hardships of the Depression, Jeff and Francis worked to support and provide a decent life for their two sons. Despite the circumstances of racism and discrimination in America, the couple placed high expectations on their children achieving the American dream in naming both their sons after prominent former US presidents Thomas Jefferson and Theodore Roosevelt. While neither parent gained more than an elementary school education, by 1940, both Thomas and Theodore had graduated high school and completed at least one year of college. Jeff continued to work in the citrus industry while Francis supplemented the family’s income through working as a laundress from the family’s home.37

As the US entered World War II, the military remained segregated by race; nevertheless, both of Howard’s sons followed in his footsteps in serving their country with distinction. As a student at Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College (now University) in Tallahassee, FL, Thomas registered during the first peacetime draft in US history on October 16, 1940, prior to US entry into the war.38 After his enlistment into the Army on April 25, 1942, following his third year of college, he reported to duty at Camp Blanding near Starke, FL.39 Thomas eventually served in India, receiving a promotion to Master Sergeant in the Army Quartermaster Corps. He served until September 9, 1945, a few days after the Japanese surrender.40

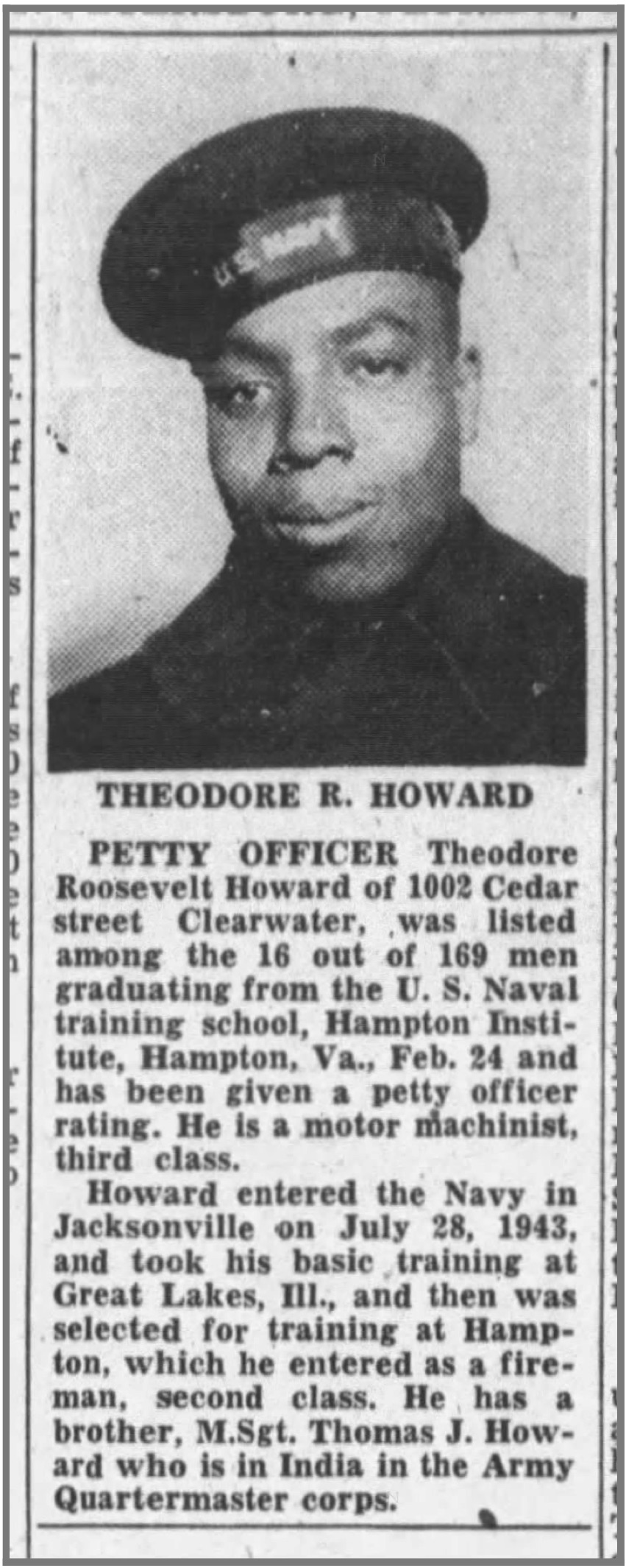

Jeff’s youngest son Theodore registered for the draft on June 30, 1942 while employed at the Bamby Bakery Company in Bridgeport, CT.41 Theodore entered the US Navy on July 28, 1943 in Jacksonville, FL, completing his basic training at the designated site for black recruits at the Naval Station Great Lakes in Illinois. Prior to 1942, the Navy limited black sailors to service as to stewards responsible for preparing and serving meals. Black leaders, however, successfully pressured the Navy to create more opportunities for blacks to serve in technical fields, though the Navy remained segregated.42 After completing basic training, the Navy selected Theodore to train at the U.S. Naval Training School at the Hampton Institute in Virginia, which also opened in 1942 to train black Navy personnel. Entering as a Fireman Second Class whose responsibilities included operating ship engines and firing boilers on ships, he graduated on February 24, 1944 with the rank of Motor Machinist's Mate Third Class Petty Officer with responsibilities including operating and repairing diesel and gasoline engines. The Tampa Bay Times, as seen here, recognized Theodore’s accomplishments in a news notice published on March 2.43 He remained in the Navy until his discharge on January 20, 1946.44

The proud parents, Jeff and Frances continued to live in Clearwater. Jeff likely spent the remainder of his working days engaged in agricultural work in the citrus industry.45 Despite facing the hardships of financial and career stagnation as a result of living in the segregated South, Howard’s tenacity ensured better prospects for his children, who furthered their education, and continued their father’s legacy with their service in World War II. Jeff Howard died on August 29, 1962. He is buried in Bay Pines National Cemetery in Saint Petersburg, FL, Row 39, Plot 5.46

Endnotes

1 “Florida, County Marriages, 1830-1957,” database, FamilySearch.org (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FWWF-N7M: accessed June 20, 2019), entry for Cage Howard and Rachael Sheppard, December 23, 1880, Alachua County, FL; “WWI Service Cards,” database, FloridaMemory.com, (https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/194318: accessed April 27, 2019), entry from Jeff Howard.

2 Maxey’s name is listed in several different variations in other documents such as Maxie and Mac. “1900 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed June 20, 2019), entry for Jefferson Howard, ED:0003, Alachua, Alachua, FL; “1900 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed June 20, 2019), entry for Cage Howard, ED:0003, Alachua, Alachua, FL.

3 Leon F. Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York: Vintage Books, 1999), 128–30.

4 “1900 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com, Cage Howard; “1900 United States Census,” Ancestry.com, Jefferson Howard; “1900 Census Instructions to Enumerators,” United States Census Bureau, August 1, 2016, accessed June 26, 2019, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/technical-documentation/questionnaires/1900/1900-instructions.html.

5 “1910 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed June 20, 2019), entry for Jeff Howard, ED:0003, Alachua, Alachua, FL; “1940 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed June 20, 2019), entry for Jeff Howard, ED:52-75, Clearwater, Pinellas, FL.

6 Russell Brooker, The American Civil Rights Movement 1865-1950: Black Agency and People of Good Will (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2017), 41-42.

7 "United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918," database with images, FamilySearch.org (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K35X-14G: accessed March 13, 2019), entry for Jeff Howard, Pinellas County, FL.

8 Eric Arnesen, Brotherhood of Color: Black Railroad Workers and the Struggle for Equality (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 22-23.

9 Theodore Kornweibel Jr., Railroads in the African American Experience: A Photographic Journey (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010, 41.

10 Arnesen, Brotherhood of Color, 43.

11 “World War I Draft Registration Cards,” National Archives, August 16, 2016, accessed June 27, 2019, https://www.archives.gov/research/military/ww1/draft-registration; Jennifer D. Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 35.

12 "United States World War I Draft Registration Cards,” FamilySearch.org, Jeff Howard; “Florida Marriages, 1830-1993,” database with images, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G94X-MS81-P?i=773&cc=1803936: accessed June 20, 2019), entry for Jeff Howard and Frances Davis, January 16, 1918, Pinellas County, FL.

13 Keene, World War I, 36-37.

14 “WWII Draft Registration Cards,” database, Fold3.com (https://www.fold3.com: accessed April 27, 2019), entry for Thomas Jefferson Howard.

15 “U.S., List of Men Ordered to Report to Local Board for Military Duty, 1917–1918,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com: accessed June 20, 2019), entry for Jeff Howard, Pinellas County, FL.

16 Keene, World War I, 95; Derrel B. Depasse, Traveling the Rainbow: The Life and Art of Joseph E. Yoakum (New York/Jackson, MS: Museum of American Folk Art/University Press of Mississippi: 2001), 11.

17 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Jeff Howard; “US Army WWI Transport Service, Passenger Lists” database, Fold3.com (https://www.fold3.com: accessed April 27, 2019), entry for Jeff Howard, USS Siboney, September 4, 1918; Richard A. Rinaldi, The United States Army in World War I: Orders of Battle, Ground Units, 1917-1919 (n.p.: Tiger Lily Publications, LLC, 2005), 101, 104.

18 The 805th Pioneer Infantry included black specialists trained at various black institutions. These included black mechanics who received training at Prairie View School in Texas, horsemen who trained at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama and carpenters who trained at what is now Howard University in Washington D.C. See Hunton and Johnson. Addie W. Hunton and Kathryn M. Johnson, Two Colored Women with the American Expeditionary Forces (Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Eagle Press, 1920), 112; Depasse, Traveling the Rainbow, 11; Eric Pace, “Herbert Young, Who Fought in World War I, Dies at 112,” New York Times, April 28, 1999.

19 Arthur E. Barbeau and Florette Henri, The Unknown Soldiers: Black American Troops in World War I (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1974), 99.

20 Depasse, Traveling the Rainbow, 11.

21 Pace, “Herbert Young.” New York Times.

22 Keene, World War I, 103; Kerrie Logan Hollihan, In the Fields and the Trenches: The Famous and the Forgotten on the Battlefields of World War I (Chicago: Chicago Review Press Inc., 2016), 92-93; Michael S. Neiberg and Harold K. Johnson, “Pershing's Decision: How the United States Fought its First Modern Coalition War,” U.S. Army, December 10, 2010, accessed July 2, 2019.

23 Pace, “Herbert Young.” New York Times.

24 “WWI Service Cards,” FloridaMemory.com, Jeff Howard.

25 Keene, World War I, 143, 151.

26 Robert J. Dalessandro, Gerald Torrence, Michael G. Knapp, Willing Patriots: Men of Color in the First World War (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Military History 2009), 56.

27 Pace, “Herbert Young.” New York Times.

28 Hunton and Johnson, Two Colored Women, 120-121; Dalessandro, Torrence, Knapp, Willing Patriots, 56.

29 Pace, “Herbert Young.” New York Times; Dalessandro, Torrence, Knapp, Willing Patriots, 56; “US Army WWI Transport Service, Passenger Lists” database, Fold3.com (https://www.fold3.com: accessed April 27, 2019), entry for Jeff Howard, USS Orizaba, June 25, 1919.

30 Return of the 807th Pioneer Regiment, ca. 1919, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers, MS 312, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, Amherst, MA, http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b219-i282.

31 “1920 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?db=1920usfedcen&indiv=try&h=4058675 : accessed June 20, 2019), entry for Jefferson Howard, ED:145, Clearwater, Pinellas, FL.

32 “WWII Draft Registration Cards,” database, Fold3.com (https://www.fold3.com/image/606147468 : accessed April 27, 2019), entry for Theodore Roosevelt Howard.

33 The years of the First Great Migration range from the mid-1910s during the outbreak of World War I through 1940, though migration slowed during the Great Depression. Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), 23, 34.

34 “1930 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com : accessed June 20, 2019), entry for Jeff Howard, ED:0050, Clearwater, Pinellas, FL.

35 Warren Firschein and Laura Kepner, A Brief History of Safety Harbor, Florida (Charleston, SC: The History Press: 2013), 63.

36 Melissa Walker and James C. Cobb, The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 11: Agriculture and Industry (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 179.

37 “1940 United States Census,” Ancestry.com, Jeff Howard.

38 “WWII Draft Registration Cards,” Fold3.com, Thomas Jefferson Howard; Carol McGinnis, Michigan Genealogy: Sources & Resources (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 2005), 85.

39 "United States World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946," database, FamilySearch.org (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KMVZ-D8S : accessed June 20, 2019), entry for Thomas J. Howard.

40 “U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com : accessed June 20, 2019), entry for Thomas Jefferson Howard; “Theodore R. Howard,” Tampa Bay Times (St. Petersburg, FL), March 02, 1944, page 13, https://www.newspapers.com.

41 Theodore registered as part of the Fifth Registration for males born between July 1, 1922 and June 30, 1924. McGinnis, Michigan Genealogy, 85.

42 “Theodore R. Howard,” Tampa Bay Times; “History,” Naval Station Great Lakes, accessed July 1, 2019, https://www.cnic.navy.mil/regions/cnrma/installations/ns_great_lakes/about/history.html.

43 “Theodore R. Howard,” Tampa Bay Times; “Hampton Institute and the Navy during the Second World War, Part II: The Compromise,” Hampton Roads Naval Museum, March 28, 2018, accessed July 1, 2019, http://hamptonroadsnavalmuseum.blogspot.com/2018/03/hampton-institute-and-navy-during.html, “US Navy Interviewer's Classification Guide,” Naval History and Heritage Command, April 28, 2015, accessed July 1, 2019, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/u/us-navy-interviewers-classification-guide.html#fire.

44 “U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com : accessed June 20, 2019), entry for Theodore Roosevelt Howard.

45 “Florida, State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry.com (https://search.ancestry.com : accessed June 20, 2019), entry for Jeff Howard, Eleventh Census of the State of Florida, 1945, Clearwater, Pinellas, FL.

46 “Howard, Jeff,” National Cemetery Administration, accessed July 11, 2019, https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/index.html?cemetery#DN830.

© 2019, University of Central Florida