Giosue Nasso (December 12, 1894–June 3, 1961)

Santina Nasso (November 12, 1911–April 24, 1989)

By Christopher Jose

Early Life

Giosue Nasso was born sometime in late 1894 in the small village of Radicena on the southern tip of Italy. Sources conflict about the exact date, with Nasso’s World War I draft registration listing his birth as October 13 and his headstone at Florida National Cemetery indicating he was born on December 12. 1

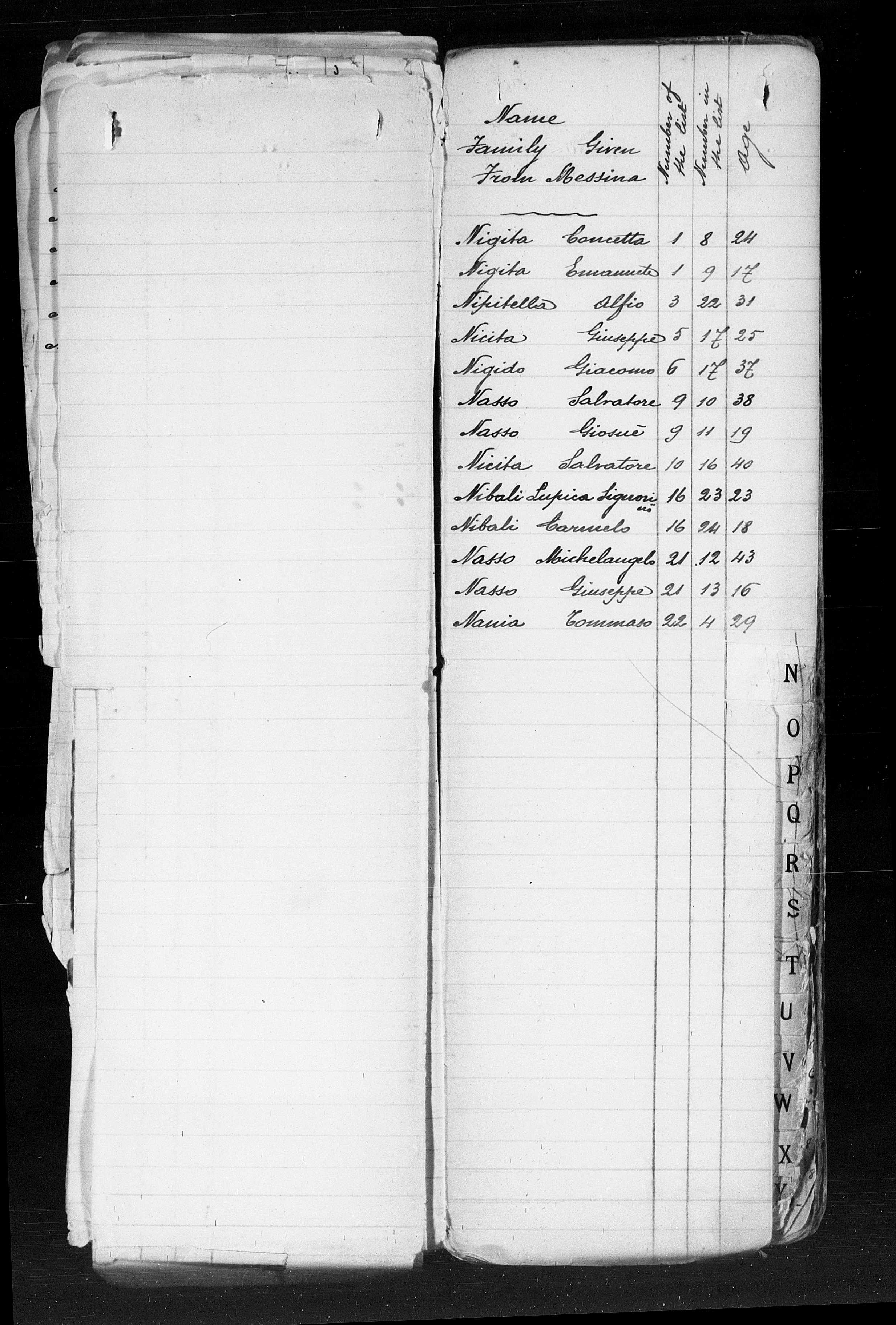

Nasso arrived in New York on April, 26, 1913 when he was nineteen years old. 2 One of the 1.1 million Italian immigrants to arrive in the United States between 1911 and 1920, Nasso’s experience reflected just how many Italians thought the US was a nation of opportunities. 3 The passenger manifest for his ship, shown here, lists Nasso as a farm worker. 4 The ship on which he booked passage, the San Guglielmo, was an Italian passenger ship that gained a reputation for ferrying Italian immigrants from Messina, Sicily, to New York City. 5 The Italians converted this vessel, like many passenger liners, into a troop transport during the First World War. A German U-boat attack sunk the San Guglielmo on January 10, 1918 off the coast of Genoa. 6

Military Service

Nasso decided to stay in New York City, working in a Navy shipping yard before registering for the draft on May 29, 1918. During World War I, he served as a Private First Class in the US Army Quartermaster Corps, which played a vital role in logistics and support for the war effort. Nasso trained with the 152nd Depot Brigade from May 29 to June 8 in Camp Upton, New York. He later transferred to the 1329 Quartermaster Corps for his tour of duty. 7 Nasso went overseas, serving in France from August 1, 1918 to September 22, 1919. In the 1329 Quartermaster Corps, Nasso worked in the Butcher Company which prepared meat for the soldiers. Even though he did not see combat, his role in supplying food to the front line played a vital part in the long and arduous battles that exemplified the First World War. The 1329 Quartermaster Corps ultimately supplied food and ammunition to the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. One of the final battles of the war, it played an instrumental role Germany’s decision to seek an armistice on November 11, 1918. 8

Post-Service Life

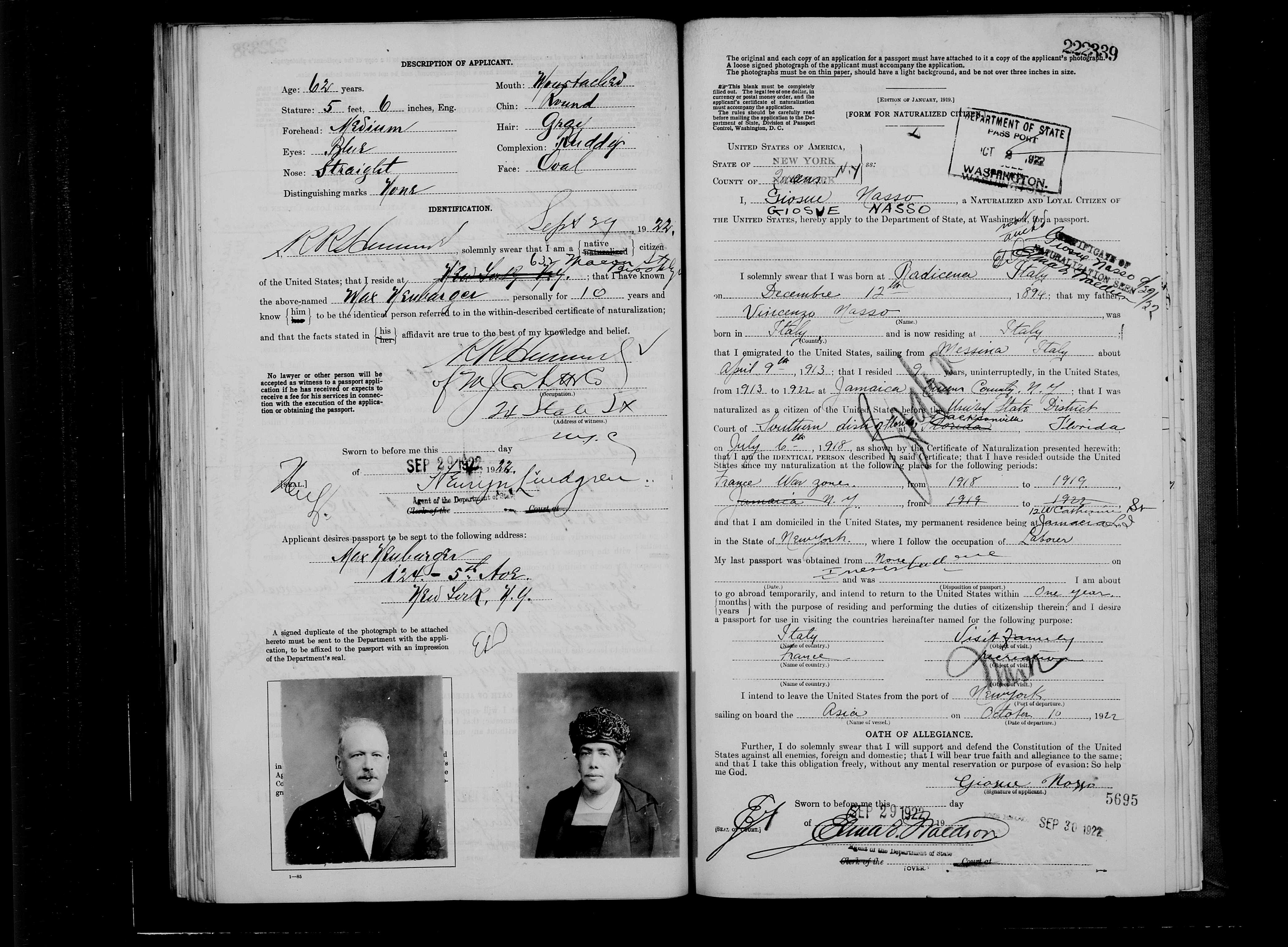

In 1922, Nasso filed for a passport in Jamaica, New York. 9 After 1924, new immigration laws curbed immigration with national quotas. Italian immigration decreased dramatically in the 1920s, from roughly two million the previous decade to 1.1 million. By 1930, the number of Italian immigrants dropped to less than 500,000. 10 Many immigrants enlisted in the First World War, at least in part, to demonstrate their loyalty to the US. Congress recognized the bravery and sacrifice of immigrant veterans. In May 1918, Congress simplified the administrative process for veterans seeking to become naturalized citizens by waving declaration of intent as well as fees. Nearly 200,000 immigrant veterans became US citizens under this provision over a thirteen month period. 11 Nevertheless, other immigrants faced ever increasing levels of discrimination as their contributions to the nation and the war faded from public consciousness and nativism increased throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. 12

Between 1922 and 1930, Nasso met and married Santina. Born in 1911 in New York City to Italian immigrants, Santina was eighteen when they married. The Nassos lived in an apartment in Brooklyn with Peter Barbaratta, likely for financial reasons. During this time, Nasso worked as an electrician. 13 By 1940, the couple had two sons, Vincent and Peter, as well as two daughters Theresa and Carmen. 14 It was around this time that the family moved from Jamaica, New York to Brooklyn. They lived in an apartment with three other boarders: Walter and Edward Benka, and Mary Gallagher. 15 Giosue lived in Brooklyn for the remainder of his life.

Giosue Nasso died on June 3, 1961 at the age of sixty-seven. He was buried in the Long Island National Cemetery in New York on June 7. At the time, the National Cemetery Administration reserved space Santina to be laid to rest with her husband. 16 She lived another twenty-eight years, moving at some point to Hernando, Florida. She requested to be interred at Florida National Cemetery due to her husband’s military service, and was buried there June 16, 1989 after passing away at the age of seventy-seven. 17 Santina also asked the National Cemetery Administration to have her husband moved and buried with her at Florida National Cemetery. Her wish seems to be highlighted on their epitaph, “together forever.” 18 Private Giosue Nasso was one of many immigrant veterans who contributed to the construction of the US in the twentieth century, a contribution that the Nasso family chose to have remembered in perpetuity at Florida National Cemetery. 19

Endnotes

1 “United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918," database with images, FamilySearch.org, https://familysearch.org (accessed December 12, 2014) entry for Giosue Nasso.“Find A Grave Index," database, FamilySearch.org, https://familysearch.org (accessed July 12, 2016) entry for Giosue Nasso.

2 “New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957,” database with images, Ancestry.com, https://ancestry.com (accessed June 7, 2017) entry for Giosue Nasso.

3 Frank J. Cavaioli, “Patterns of Italian Immigration to the United States,” The Catholic Social Science Review 13 (2008): 220.

4 “New York Book Indexes to Passenger Lists, 1906-1942," database with images, FamilySearch.org, https://familysearch.org (accessed November 10, 2016) entry for Giosué Nasso.

5 Ibid.

6 “Marine Insurance Experience During War and Future Outlook,” Insurance Newsweek 20, January 31, 1919: 6.

7 “New York Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917-1919” database with images Fold3.com, https://fold3.com (accessed June 8, 2017) entry for Giosue Nasso, army service number 3197861.

8 “Records of the American Expeditionary Forces (World War I), National Archives, https://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/120.html#120.9.4 (accessed June 6, 2017), entry for Giosue Nasso.

9 "United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925," database with images, FamilySearch.org, https://familysearch.org (accessed September 4, 2015) entry for Giosue Nasso.

10 Cavaioli, “Patterns of Italian Immigration,” 220.

11 Mary Evelyn Tomlin, “Becoming American: Immigration and Naturalization Records in the National Archives,” in Immigration and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman, ed. Roger Daniels (Kirksville, MO: Truman State University Press, 2010), 179.

12 Christopher Sterba, Good Americans: Italian and Jewish Immigrants During the First World War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 8.

13 “United States Census, 1930,” database with images, Ancestry.com, https://ancestry.com (accessed June 8, 2017) entry for Santina Nasso.

14 “United States Census, 1940” database with images, Ancestry.com, https://ancestry.com (accessed June 8, 2017) entry for Giosue Nasso.

15 Ibid.

16 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database with images, Ancestry.com, https://ancestry.com (accessed June 12, 2017) entry for Giosue Nasso.

17 “Florida Death Index, 1877-1998,” database, Ancestry.com, http://ancestry.com (accessed June 8, 2017) entry for Santina Nasso.

18 National Cemetery Administration, “Long Island National Cemetery Map,”va.gov, gravelocator.cem.va.gov/NGLMap?ID=715031 (accessed June 12, 2017).

19 National Cemetery Administration, "Giosue Nasso," US Department of Veterans Affairs, accessed June 12, 2017, https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/NGLMap?ID=1955610

© 2017, University of Central Florida