Willie Roberts (March 25, 1892–February 29, 1992)

By Jeremy M. Bell

Early Life

Born on March 25, 1892, Willie Roberts grew up in the town of Starke, located in Bradford County, Florida. His mother Annie Brookins grew up in Virginia where her birth in 1865 coincided with the conclusion of the Civil War.1 As African-Americans living in the Jim Crow South, Roberts and his family certainly faced many hardships. Black codes established in Florida after the Civil War, as well as Jim Crow laws in the 1880s and 1890s, greatly reduced the political, economic and legal status of blacks in Florida.2 In addition, the threats and actual violence conducted by whites in Florida made the state a dangerous place for African-Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

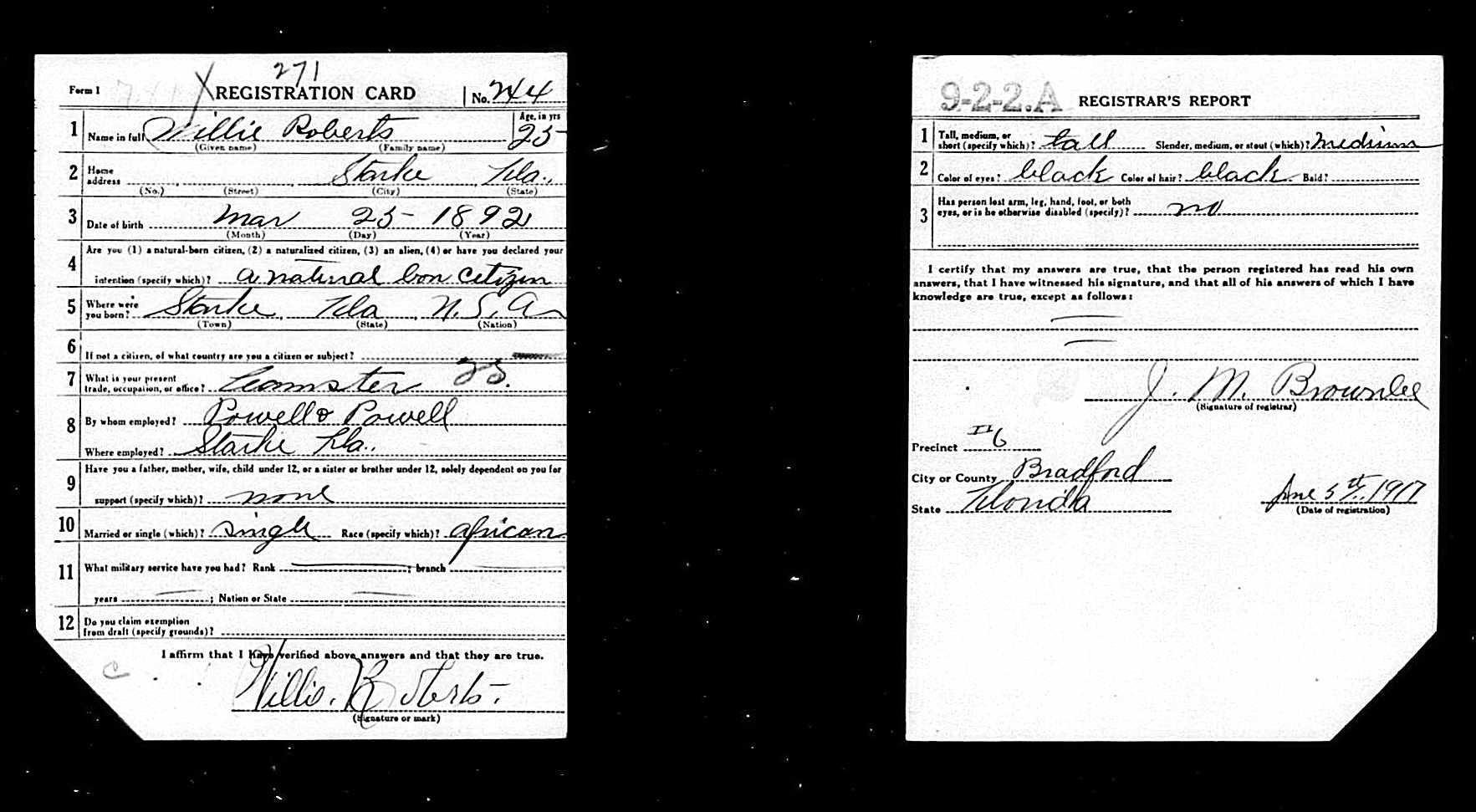

Bradford County proved to be a typical rural North Florida county with little manufacturing, minimum tourism appeal, and a higher black population in relation to other Florida counties.3 Roberts and his family did not live on a farm; they worked as laborers within the community. By 1915, Roberts’ family included a daughter named Geneve.4 At the time of Willie’s registration on June 5, 1917, Willie was a teamster at a local company in Starke, which we see noted on his military registration card.5 Black and white teamsters in the early twentieth century drove passenger wagons known as hacks or freight hauling and delivery wagons called trucks or drays. Significantly, in the first two decades of the twentieth century the International Brotherhood of Teamsters became an interracial coalition of unions fighting for better wages and working conditions despite the deep structural racial discrimination of the time.6

Service: Roberts and African-Americans in World War I

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, thousands of young men enlisted in the military, yet recruiting stations often refused black recruits. In seeking to find a place for black recruits, the General Staff of the Army considered training segregated black combat troops and placing them in various camps across the country. White paranoia about arming black men, especially in the South, forced the Army to table this plan.7 By 1918, the Wilson administration helped to ensure that the military establishment closed ranks against blacks in combat, though a few black segregated combat troops served under the French.8 In seeking to utilize black recruits, the Secretary of War Newton Baker instead mandated that black draftees serve in the Quartermaster and Engineer Corps, providing menial and unskilled labor for the Army.9 It is likely that Roberts—who registered for the draft on June 5, 1917 but waited until April 26, 1918 for his assignment in the Army’s Reserve Labor Battalion, Quartermaster Corps—experienced this situation.10 Of the over 367,000 black draftees, eighty-nine percent (including Roberts) served within the Quartermaster and Engineers Corps in labor, supply and service units.11 Perhaps due to his experience as a teamster, his labor involved transporting supplies and labor goods. Whatever role he played, blacks like Roberts served their country dutifully and faithfully, despite facing discrimination and segregation inside and outside the military. After the war ended, Roberts received an honorable discharge on April 11, 1919.12

Postwar: Settling in Florida and Life as a Train Porter

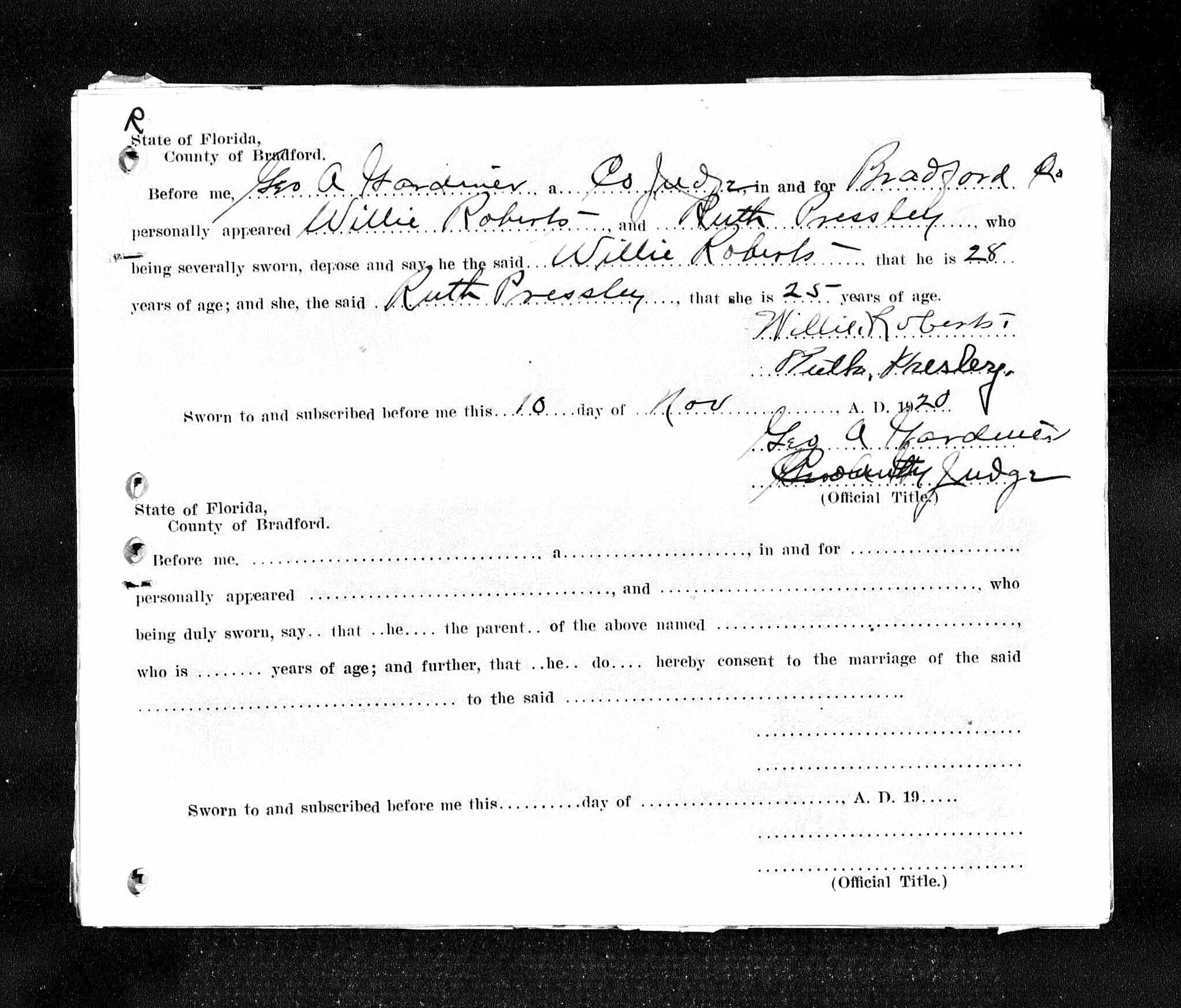

After his release from the Army, Roberts married Ruth Pressley in 1920, as we see in this copy of their marriage license. Willie, Ruth, and Geneve lived with Roberts’ brother D.E. Roberts and his family in Orlando. The 1920 Census lists Roberts’s employment as a laborer for a local wholesale company.13 While some African-Americans in the South migrated to urban cities in the North and Midwest, those who remained often moved from the rural to urban areas of the South.14 By 1930, the Roberts family moved back to Starke, living with Roberts’ mother Annie. The family owned their own home, worth about $1000, and Roberts supported the family as a general laborer. By the 1935 Florida State Census, Roberts transitioned to working in the railroad industry in Bradford County. Around this time, his daughter Geneve married and moved out of the household.15 In this context, an African-American living in rural Florida during the Great Depression, Roberts supported his family the most efficient way he could.

Eventually, Roberts, like many other rural blacks before him, moved his family from a rural to an urban center. By the 1940 Census, the family relocated from Starke to Jacksonville where Roberts worked as a train porter—a job position popular among blacks after the Pullman Rail Car Company began hiring men recently freed following the end of the Civil War.16 The lure of the city, as well as greater occupation opportunities, proved beneficial for the family. Train porters’ responsibilities in serving white passengers ranged from handling passengers’ cargo luggage to shining their shoes.17 In addition, the job offered prestigious status within the black community. Porters helped to shape the modern black middle class; their experiences observing the “white world” in sleeping cars and traveling the country inspired train porters to organize the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters, an organization led by A. Philip Randolph, a Jacksonville native.18 Train porters like Roberts proved vital in their involvement in fighting for labor and civil rights for African-Americans.

Roberts' occupation offered better wages that allowed him and his family to become homeowners and stay in their Jacksonville home for at least thirty years. Willie Roberts died on February 29, 1992 in Lake City, Florida.19 In his ninety-nine years, Willie accomplished a great deal and helped to create the African-American middle class. In this respect, he lived the American dream. He worked hard to provide Ruth and their children with a better life. He now rests at Florida National Cemetery in Bushnell, Florida in Section 104.20

Endnotes

1 1930 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed April 5, 2017), entry for Willie Roberts, Bradford, Florida, United States; ED 3, sheet 10A, line 41, family 200, NARA microfilm publication T626.

2 Jerrell H. Shofner, “Custom, Law, and History: The Enduring Influence of Florida’s ‘Black Code,’” The Florida Historical Quarterly 55, no. 3 (1977): 290–91.

3 H. T. Grace, “A Survey of the Economic, Educational and Social Resources of Bradford County, Florida,” Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 18, no. 4 (1955): 240.

4 "U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007." database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed April 5, 2017)

5 "U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database with images, Ancestry.com (http://ancestry.com: accessed April 5, 2017), entry for Willie Roberts.

6 David Witwer, “Race Relations in the Early Teamsters Union,” Labor History 43, no. 4 (November 1, 2002): 511, doi:10.1080/00236560220127194.

7 Jennifer Keene, “A Comparative Study of White and Black American Soldiers during the First World War, Summary,” Annales de Démographie Historique no 103, no. 1 (October 1, 2005): 73–74, http://www.cairn-int.info/article-E_ADH_103_0071--a-comparative-study-of-white-and-black.htm.

8 Gail Lumet Buckley, American Patriots: The Story of Blacks in the Military from the Revolution to Desert Storm (Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2002), 163–64.

9 Keene, “A Comparative Study of White and Black American Soldiers during the First World War, Summary,” 74.

10 "U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” Ancestry.com; “Florida, World War I Service Card, 1917-1919,” FamilySearch.org (https://familysearch.org : accessed 28 June 2017), entry for Willie Roberts.

11 Buckley, American Patriots, 164–65; Keene, “A Comparative Study of White and Black American Soldiers during the First World War, Summary,” 74.

12 “Florida, World War I Service Card, 1917-1919,” FamilySearch.org.

13 "Florida, County Marriages, 1823-1982,” database with images, Ancestry.com: accessed April 5, 2017), entry for Willie Roberts and Ruth Plessley, Bradford County, Florida; "1920 United States Census," database with images, FamilySearch.org (https://familysearch.org : accessed June, 22 2017), D E Roberts, Orlando, Orange, Florida, United States; citing ED 117, sheet 5B, line 82, family 133, NARA microfilm publication T625.

14 Grace, “A Survey of the Economic, Educational and Social Resources of Bradford County, Florida,” 246–47.

15 "1935 Florida State Census," database with images, FamilySearch.org (https://familysearch.org : accessed June 22, 2017), Willie Roberts, Starke, Bradford, Florida; citing line 15, State Archives, Tallahassee; FHL microfilm 2,425,148.

16 “1940 United States Census,” database, Ancestry.com (http:/www.ancestry.com : accessed 5 April 2017), entry for Willie Roberts, Starke, Florida

17 Larry Tye, Rising from the Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle Class (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2005), xiii.

18 Ibid., xii, 113-167.

19 “U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014,”, database, Ancestry.com (http:/www.ancestry.com : accessed April 13, 2017), entry for Willie Roberts.

20National Cemetery Administration, "Willie Roberts," US Department of Veterans Affairs, accessed September 18, 2018, https://gravelocator.cem.va.gov/NGLMap?ID=2056276

© 2017, University of Central Florida