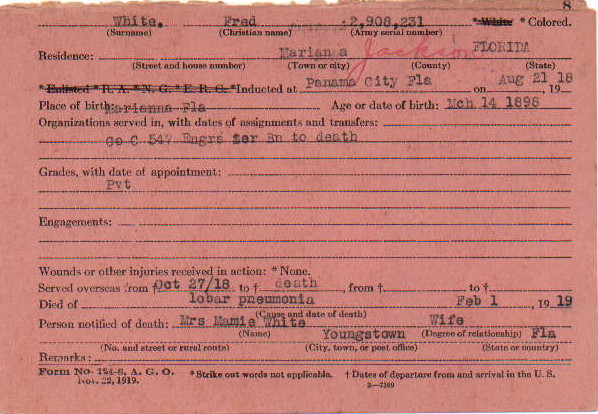

Fred White (March 14, 1898–February 1, 1919)

By Danielle Dickey

Early Life

Fred White was born on March 14, 1898, in Marianna, Florida.1 According to the 1910 Census, Fred lived with his grandparents Isaac Sr. and Adline White and their children in Cottondale, Florida. Fred’s grandmother Adline gave birth to fourteen children, with eleven still living by 1910. It is probable that the death of one of Isaac and Adline’s older three children, Fred’s mother or father, necessitated Fred moving in with his grandparents.2 Thus, Fred lived with his extended family, including his aunts and uncles, some around his age. Like many black families in the rural South, the White family farmed. While the vast majority of black farmers in the South worked as tenants, sharecroppers or wage hands in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, African Americans dreamed of owning and tilling their own land. In the South, one out of every five black families owned their own land, a proportion that rose to one out of every four black families in 1910. By 1900, Fred’s grandfather Isaac Sr. achieved the dream of many African Americans, owning and working his own land. Each member of the family, including Fred, contributed to the operation of the family farm, a symbol of black independence. The White family was becoming part of a slowly developing rural black middle class in the South.3

Likewise, the family valued education and literacy as each family member in 1910 could read and all but Fred’s grandmother could write. In 1910, White and some of his aunts and uncles fulfilled their responsibilities on the family farm while attending school in the local area. Like land ownership, African Americans viewed education as a means of social respect and independence within American society; White’s grandparents certainly helped instill these values in their children and grandchildren.4 By 1918, White, nineteen, moved to Youngstown in neighboring Bay County. White worked for Benjamin Hill Dickens, a carpenter with the American Lumber Company in Millville (today part of Panama City), who owned land in the area. White likely worked as a laborer under Dickens at the lumber company or on Dickens’s land.5 On June 15, 1918, White married Mamie Grey Kennedy in Bay County, Florida.6

Military Service

Shortly before his marriage to Mamie, Fred registered for the military draft. When the US entered World War I in 1917, Congress passed the Selective Service Act to increase the manpower of the military through conscription. The first registration took place on June 5, 1917, which required all men in the US between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-one to register. The second registration took place a year later on June 5, 1918, for individuals who turned twenty-one after June 1917.7 White, then only twenty years old, listed his birth year on the registration card as 1897, as seen here, making himself eligible for the draft. Personal and patriotic reasons helped motivated African Americans to register and volunteer for military service. On average, soldiers earned more money—usually thirty dollars per month—than if they worked as a laborer or farmer, a significant financial benefit for many black families. Additionally, African Americans, used the war as an opportunity to demonstrate their bravery and loyalty to America, and hoped in turn that white society would view and treat them as equals. Thus, thousands of blacks registered, many, like White, even lied about their age to join the war effort.8

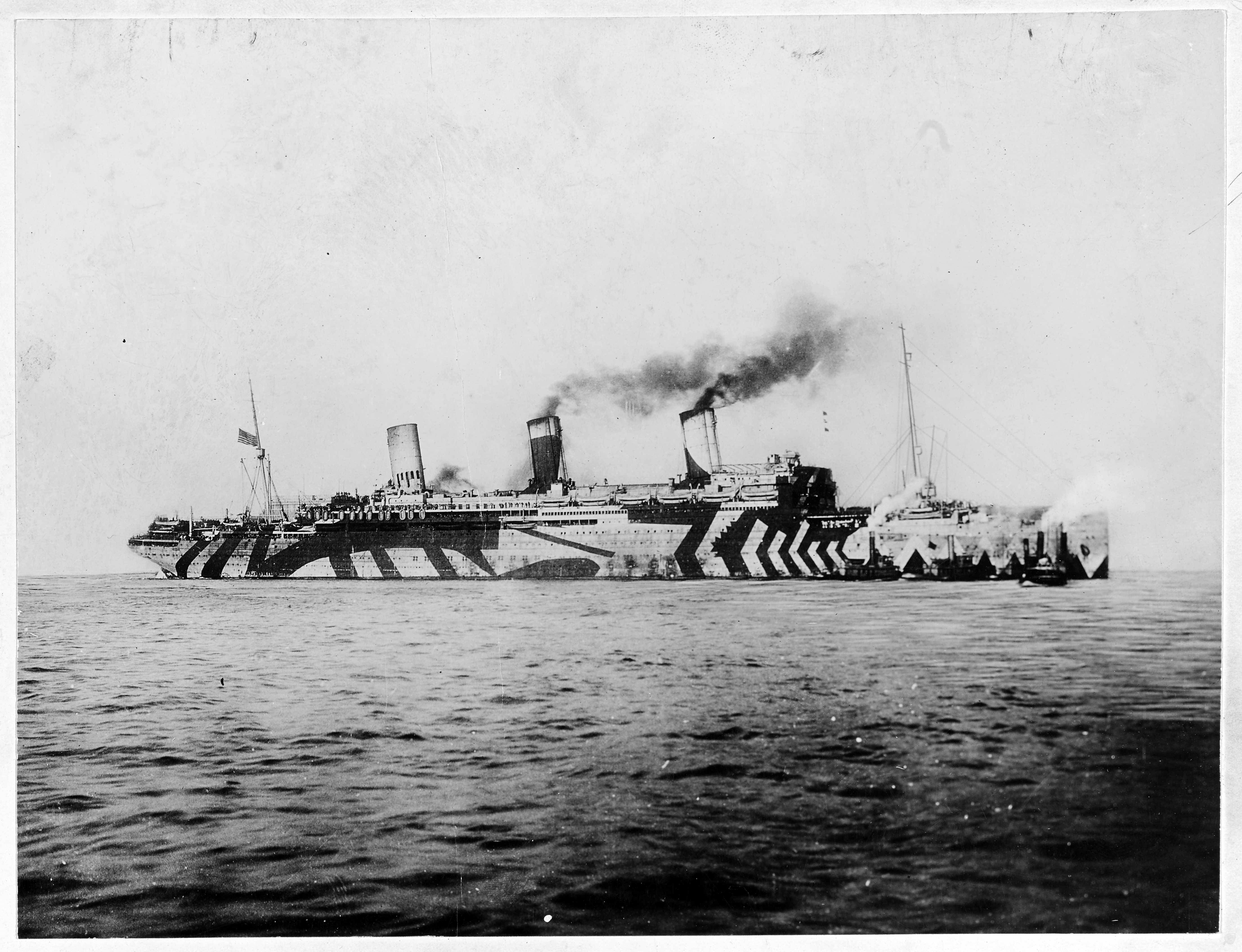

Overall, the military drafted thirty-six percent of black registrants compared to twenty-five percent of white registrants. In Florida, the military drafted 12,904 black men compared to 12,769 white men.9 A month after his marriage to Mamie, the Army drafted White on August 21, 1918, sending him to train at Camp Joseph E. Johnston, a newly established Quartermaster Training Camp outside of Jacksonville, Florida. Amid the Jim Crow era of segregation, the Army trained black soldiers in segregated units. Additionally, white Southerners’ fears about blacks potentially gaining military training in firearms pressured military officials to largely place African Americans like White in Quartermaster and Engineering units which required minimum training of firearms.10 After training at Camp Johnston, White joined the 547th Engineer Service as part of Company C, which first organized in September 1918 at Camp Humphreys, Virginia. The unit later transferred to Camp Merritt, New Jersey, in October 1918.11 On October 27, White and his battalion left Hoboken, New Jersey, aboard the USS Leviathan, the largest transport fleet of the US military, as shown here, headed to France.12

Engineer battalions like the 547th consisted of a Headquarters Detachment, four companies and a medical department with a force of about 1,040 men. Each company consisted of three officers and 250 soldiers equipped with a half-ton motor truck, two two-ton motor trucks, a water cart and two motorcycles with a sidecar. Engineer battalions’ main responsibility consisted of building bridges, building and repairing roads, and completing other general engineering tasks. While trained in the use of firearms, the Army did not permit black engineering battalions to carry arms in France, even though these engineering units served in the heat of battle.13 As one corporal in the 546th battalion exclaimed, “Although some of us worked quite close behind the lines, within range of shot and shell, we did not see arms except such as lay discarded about the woods and in the field.”14 Since White’s unit left for France on October 27, it is unlikely the 547th saw action upon arriving as Germany sued for peace and signed an armistice on November 11, 1918, ending the war. Had the war continued, White and his unit certainly would have contributed as other service and supply units had to the overall war effort.15

Instead, White and his unit contributed in some capacity to the immediate and necessary post war work, including rebuilding French infrastructure and burying the dead.16 After serving for less than three months in France, White fell ill to influenza. The influenza and pneumonia epidemic of 1918 and 1919 killed more US soldiers and individuals across the world than enemy weapons. While initially segregation within the Army shielded some black regiments from infection, overall, black regiments experienced higher mortality rates than white regiments. The factors of inferior living conditions, insufficient clothing and food, and hard outdoor manual labor, including burial duty, in inclement, winter weather, intensified the spread of the disease among black troops. While white medical officers claimed that blacks’ inferiority made them more susceptible to disease, in reality, the discrimination among white medical personnel meant many black soldiers avoided medical care. By the time they received medical care, their worsened condition largely proved too late for recovery. On February 1, 1919, a month short of his twenty-first birthday, Fred White died in France of lobar pneumonia with the Army notifying his wife Mamie back in Youngstown.17

Legacy

From the farms of rural Florida, White’s life reflected the values of diligence, hard work and a willingness to serve. While his true age exempted him from having to register for military service in 1918, White proved willing to serve his country, even as many white Americans viewed him and other African Americans as inferior. As one African American soldier proclaimed after the war, “We offered our lives to save this country and we are willing to give our lives for our rights.” While pneumonia prematurely ended White’s life, his legacy, along with the legacies of other fallen black soldiers who fought for freedom both overseas and at home, carried over to surviving black veterans. They continued the fight for fairness and equality in America.18 Fred White is buried in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, Plot C Row 7 Grave 3 in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, France.19

Endnotes

1 “Fred White,” database, FloridaMemory (https://www.floridamemory.com : accessed March 26, 2018).

2 “1885 Florida State Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed June 25, 2018), entry for Isaac B. White, Jackson County, Florida; “1910 United States Federal Census.” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com: accessed February 19, 2018), entry for Fred White, Cottondale, Jackson, Florida.

3 “1910 United States Federal Census.” database, Ancestry.com; Leon F. Litwack, Trouble In Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1998) 128-130; Mark Schultz, The Rural Face of White Supremacy: Beyond Jim Crow (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2007), 45.

4 “1910 United States Federal Census.”database, Ancestry.com, Fred White; Schultz, The Rural Face of White Supremacy, 16.

5 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed June 26, 2018), entry for Fred White; “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed June 26, 2018), entry for Benjamin Hill Dickens; “U.S., Lists of Men Ordered to Report to Local Board for Military Duty, 1917–1918.” database, Ancestry.com (http://www.ancestry.com : accessed June 26, 2018), entry for Fred White; “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed June 26, 2018), entry for Benjimen sic H. Dickens; Millville, Washington, Florida; Benjamin H. Dickens. General Land Office. Serial Patent 296956, issued October 17, 1912. https://glorecords.blm.gov/details/patent/default.aspx?accession=296956&docClass=SER&sid=g1dgblk2.fw5#patentDetailsTabIndex=1.

6 “Florida, County Marriages, 1830-1957,” database, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org : accessed 26 June 2018), entry for Fred White and Mannie Gray Kennedy, June 15 1918, Bay County, Florida.

7 Jennifer D. Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 33-37; “World War I Draft Registration Cards,” National Archives, accessed June 27, 2018, https://www.archives.gov/research/military/ww1/draft-registration.

8 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database Ancestry.com, Fred White; Keene, World War I 37, 189; Nina Mjagkij, Loyalty in Time of Trial: The African American Experience During World War I (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing, Inc., 2011), 81.

9 Keene, World War I, 37; Emmett J. Scott, Scott’s Official History of the American Negro in the World War. (Chicago: Homewood Press, c1919), 67.

10 Keene, World War I, 95; Ronald M. Williamson, Naval Air Station Jacksonville, Florida, 1940-2000: An Illustrated History (Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company, 2000), 13.

11 Robert J. Dalessandro and Gerald Torrence, Willing Patriots: Men of Color in the First World War (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2009), 25; “Fred White,” FloridaMemory; “U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939,” database, Ancestry.com (https://www.ancestry.com : accessed March 26, 2018), entry for Fred White, Youngstown, Florida.

12 “U.S., WWI Troop Transport Ships, 1918-1919,” database, Ancestry.com(https://www.ancestry.com : accessed June 26, 2018), entry for Leviathan; Bill McClellan, “Story of USS Leviathan is a Mesmerizing Tale of the Great War,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch (St. Louis, MO), July 14, 1917.

13 Dalessandro and Torrence, Willing Patriots, 16-17.

14 Dalessandro and Torrence, Willing Patriots, 17.

15 Keene, World War I, 24; Derrel B. Depasse, Traveling the Rainbow: The Life and Art of Joseph E. Yoakum (New York/Jackson, MS: Museum of American Folk Art/University Press of Mississippi, 2001), 11.

16 Spencer Tucker, ed., World War I: A Student Encyclopedia, vol. 1 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2006), 2316.

17 Keene, World War I, 167-168; Carol R. Byerly, "The U.S. Military and the Influenza Pandemic of 1918–1919." Public Health Reports 125, no. Suppl. 3 (2010), 82, 88, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2862337/; Pace, “Herbert Young, Who Fought in World War I, Dies at 112; “Fred White,” FloridaMemory.

18 Keene, World War I, 189.

19 “Fred White,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed June 27, 2018, https://www.abmc.gov/node/329776#.WzRT2i2ZMWo.

© 2018, University of Central Florida