Thomas (Hernandez) Hanandos (c. 1842–November 24, 1915)

By Sara Nazarian

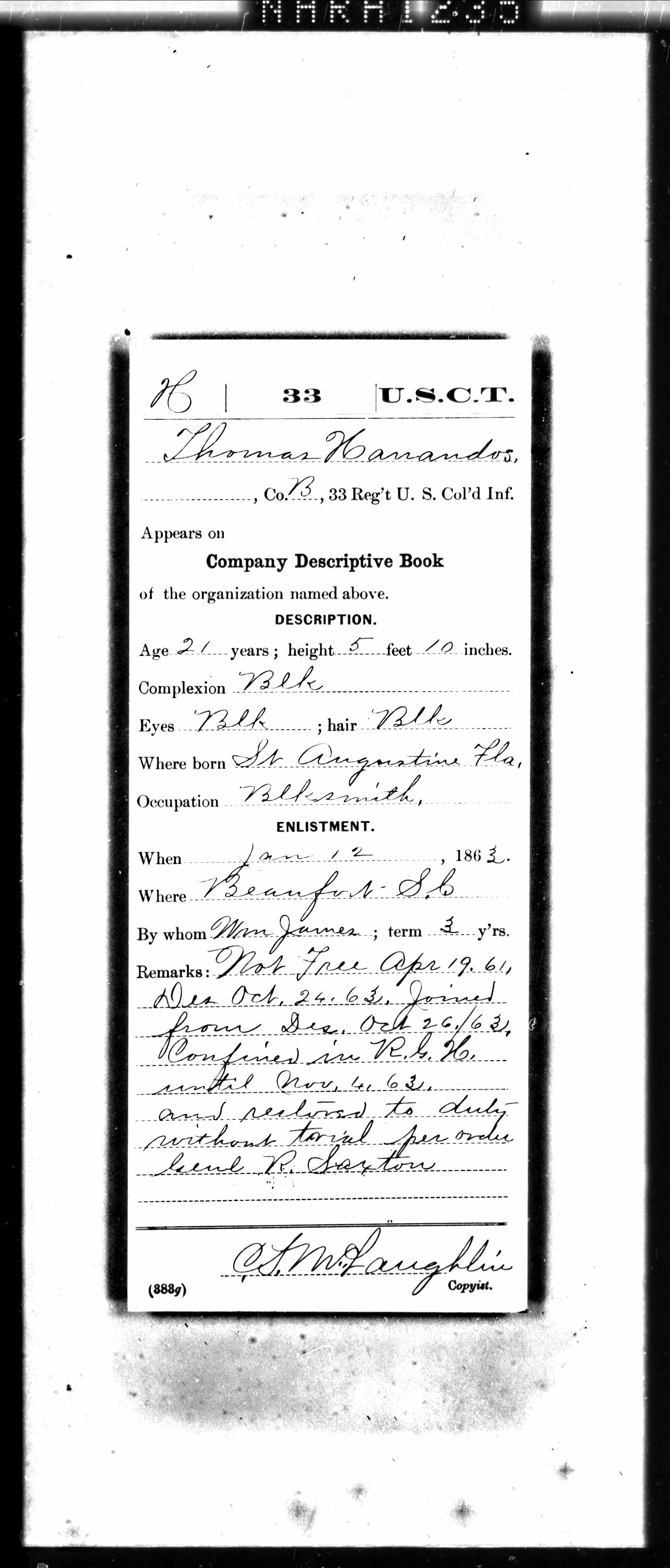

During the Civil War, Thomas Hanandos, also known as Thomas Hernandez, served as a Private in the Thirty-third United States Colored Infantry (USCI). Born in Saint Augustine, Florida, he was a slave as of April 19, 1861. Hanandos ran away to South Carolina and worked as a blacksmith before entering service.1

After the seceded states of the Confederacy bombarded Fort Sumter, the war began. Initially, the government rejected the service of African Americans because the war was about maintaining the Union with slavery. On September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. It went into effect January 1, 1863, prompting the Army to recruit black soldiers. In Beaufort, South Carolina, former slaves gathered to hear the reading of the final proclamation on January 12, 1863 at Camp Saxton. On the same day, Hanandos enlisted into Company B, First Regiment South Carolina Volunteer Infantry at the age of twenty-one, as seen here. He was mustered in on January 31, 1863, the same day the regiment was officially formed, for a period of three years. The regiment helped capture Jacksonville, Florida on March 10, 1863.2

Like other black soldiers, he was not paid the same as his white comrades. Initially, from the time of his enlistment to February 28, 1863, he received a pay of thirteen dollars. From February 28 to October 31, his pay was reduced to ten dollars. From October 31 to February 29, 1864, his pay was reduced once again to seven dollars; the three dollar difference was for his clothing. Likely, as a result of this unfair treatment, Hanandos deserted from Camp Shaw in South Carolina on October 21, 1863. He came back on October 24, 1863 and was detained by Army officials, where he awaited trial until November 4. Ultimately, he was released back to active duty under the orders of Rufus Saxton, a Union Army brigadier general. Saxton may have recognized the injustice that prompted him to leave camp. Hanandos received his full pay on June 15, 1864 after Congress passed a bill equalizing pay for black soldiers.3

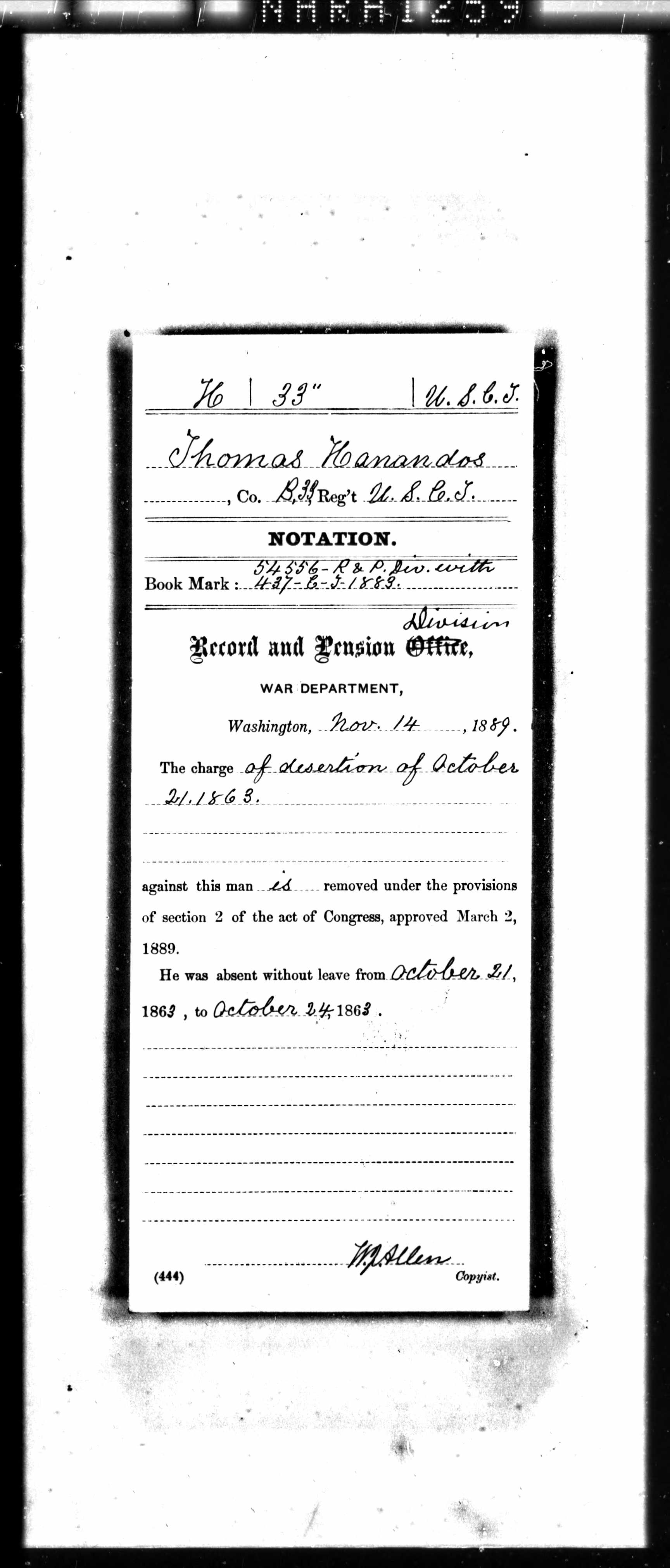

Sometime after Hanandos was released on February 8, 1864, the First South Carolina Volunteer Infantry was designated the Thirty-third United States Colored Infantry (USCI). The regiment participated in the capture of the Battery Gregg on James Island, South Carolina near Charleston and the Battle of Honey Hill, South Carolina. During its last year of service, the regiment served with the Union garrison of Savannah and Charleston. Hanandos was mustered out in Charleston, South Carolina on January 31, 1866. He owed $25.24 to the United States government and $2.20 in equipage fees. He was not legally acquitted for the charge of desertion until November 14, 1889, when the charge was changed to absent without leave, as seen here.4

After the war in 1866, Hanandos applied for provisions at the Freedmen's Bureau alongside fellow war veterans William Hewlin and Martin Nateel. He started receiving an Army pension in 1889. Little is known about his life other than his interactions with the federal government. Hanandos at some point also changed his last name to Hernandez. Former slaves often changed their name after the war. Hanandos died on November 24, 1915 and was later interred at the Saint Augustine National Cemetery in Section A, Grave Number 190. His name also appears on the African American Civil War Memorial on plaque B-49.5

Endnotes

1 “U.S. Colored Troops Military Service Records, 1863-1865,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com : accessed July 3, 2019), entry for Thomas Hanandos.

2 Matthew Pinsker, “Emancipation Among Black Troops in South Carolina,” Emancipation Digital Classroom, November 06, 2012, accessed July 3, 2019, http://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/emancipation/2012/11/06/emancipation-among-black-troops-in-south-carolina/; “U.S., Colored Troops Military Service Records,” Ancestry.com, Thomas Hanandos; “Guide to the 1st South Carolina / 33 Rd U.S. Colored Troops Records,” Online Archive of California, accessed July, 3, 2019, https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0d5n99qh/entire_text/.

3 “U.S., Colored Troops Military Service Records,” Ancestry.com, Thomas Hanandos; “Sergeant Francis Fletcher of the 54th Massachusetts on equal pay for black soldiers, 1864,” History Now, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, accessed July 22, 2019, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/content/sergeant-francis-fletcher-54th-massachusetts-equal-pay-black-soldiers-1864.

4 “Guide to the 1st South Carolina,” Online Archive of California; “U.S., Colored Troops Military Service Records,” Ancestry.com, Thomas Hanandos.

5 “United States, Freedmen’s Bureau Claim Records, 1865-1872,” database, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org : accessed July 3, 2019), entry for William Hewlin; “United States Index to General Correspondence of the Pension Office, 1889-1904,” database, FamilySearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org : accessed July 3, 2019), entry for Thos Hanandos; “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com : accessed July 3, 2019), entry for Thomas Hernandez; “ U.S. Civil War Soldiers, 1861-1865,” database, Ancestry.com (https://ancestry.com : accessed July 3, 2019), entry for Thomas Hanandos.

© 2019, University of Central Florida