Horace H. Adams Jr. (January 15, 1919-July 20, 1944)

119th Infantry Regiment, 30th Infantry Division, US Army

By Holly Roush and Oliver Brown

Early Life

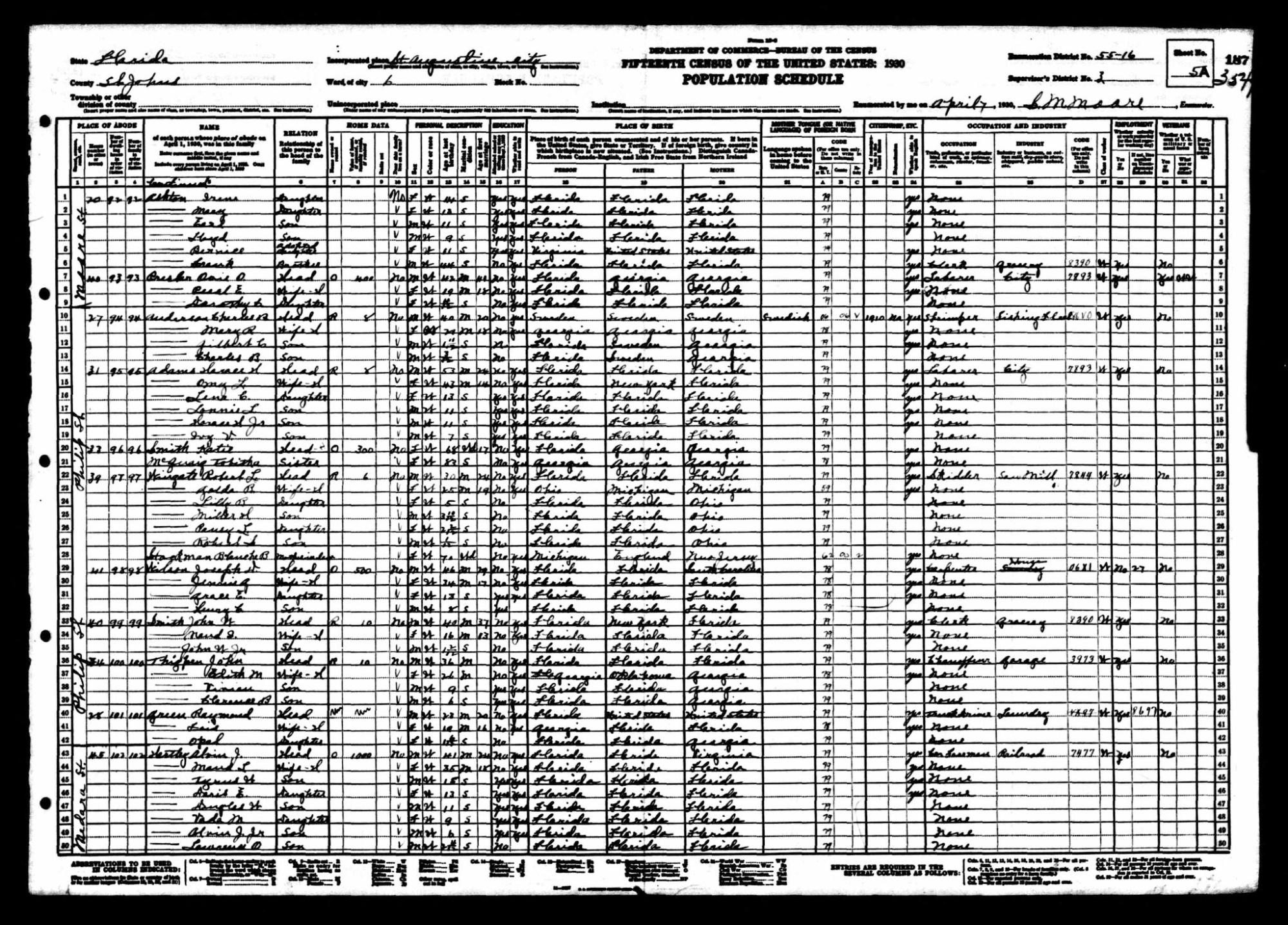

Horace H. Adams Jr. was born on January 15, 1919, in St. Augustine, FL, to Horace Adams Sr. and Omy Louise (née Smith) Adams.1 Horace Sr. was born on October 26, 1875, in St. Johns County, FL.2 Omy Louise was born on January 11, 1886, also in St. Johns County.3 On March 7, 1901, when he was twenty-five, Horace Sr. married Omy Louise Smith, then fifteen years old.4 In 1900, shortly before his marriage, Horace worked as a laborer in a mill in St. Johns County.5 He remained a laborer for the next three decades, likely in the timber industry, as he worked as a wood chopper in 1910.6 Timber became a lucrative industry in Florida around the turn of the twentieth century, as land developers began to target the state. By the 1910s, as Horace Sr. and Omy Louise grew their family, Florida lumber workers produced about a billion board feet ( A board foot is one-foot in length, one-foot in width, and one-inch thick) annually.7 The couple had a total of nine children during this time, including Horace Jr. and his twin brother Lonnie in 1919. Omy Louise additionally gave birth to Carmen in 1902, Cora in 1904, Emery in 1905, Colley in 1908, Bertie in 1910, Lawrence in 1912, and Ivy in 1923. In 1930, the Adamses resided in St. Augustine, FL in a family-owned residence valued at $200, noted here.8

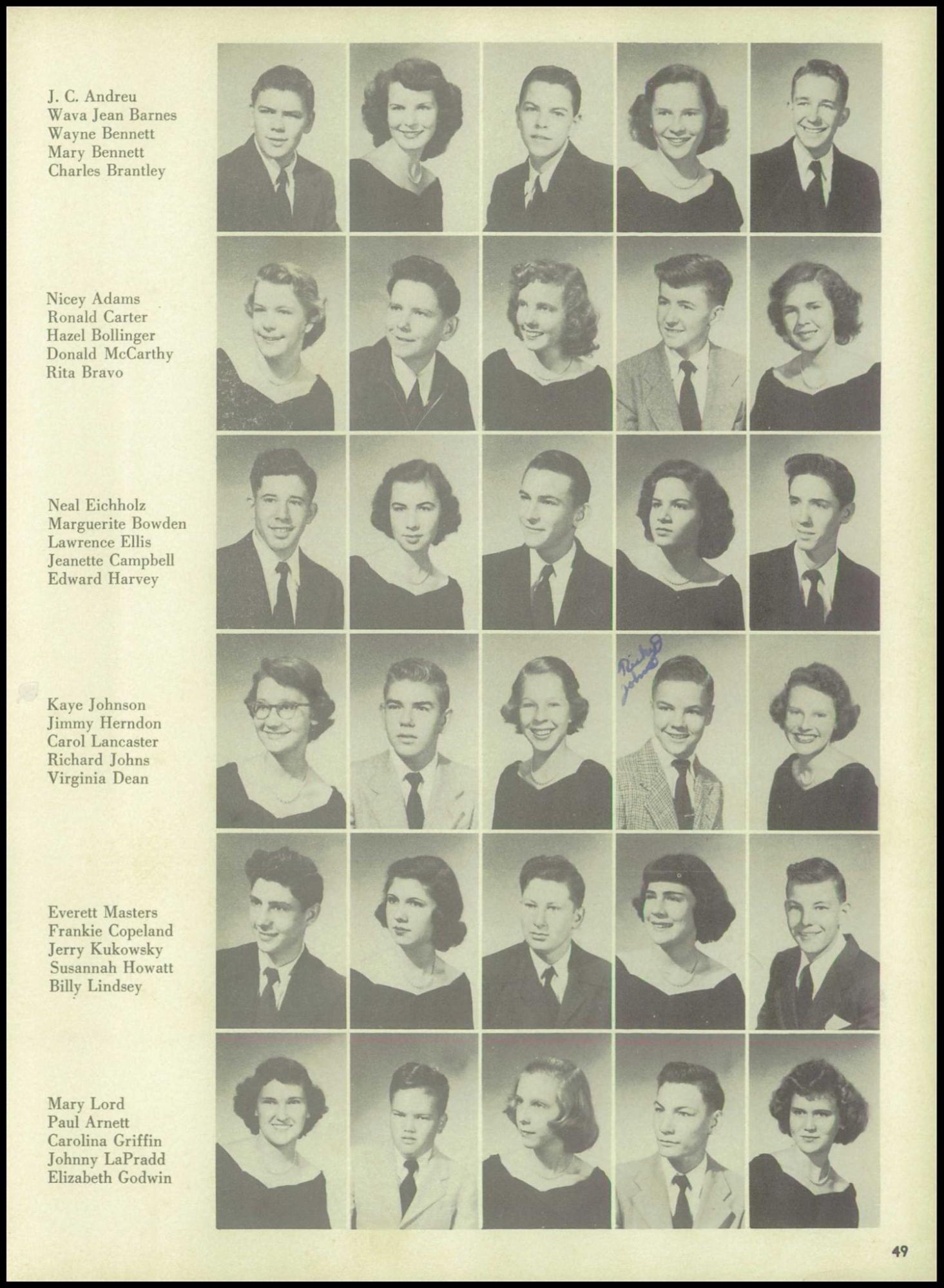

Horace Jr. completed the seventh grade, but in the years after the Great Depression began following the stock market collapse in October 1929, he joined the workforce rather than continue his schooling in order to help add to the family’s income, as many teenagers did at the time.9 Unfortunately, tragedy struck the Adams family in the early 1930s, when Horace Sr. passed away from heart failure on January 29, 1933, at the height of the Depression, which left Horace Jr., his mother, and his elder siblings to provide for the family.10 By 1940, Horace Jr. worked as a truck driver for a wholesale grocery company, earning an annual salary of $624, while living with his mother, grandmother, and younger brother Ivy. The same year, his mother, Omy Louise, worked as a seamstress employed by the Works Progress Administration.11 This government program, established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1930s, enabled millions of Americans to work during the Depression years.12 In the midst of these challenges, Horace Jr. married Matty E. Colee sometime before 1938 and had a daughter, Nicey Louise, in 1938.13 Later that same year, after the birth of their daughter, the couple divorced.14 After the divorce, Horace Jr.’s ex-wife Matty worked as a waitress. She and their daughter lived with Matty’s mother in St. Augustine, FL.15 On January 2, 1942, Horace Jr. married once more to Nellie Wheeler in Clay County, FL.16

Military Service

On November 18, 1935, at the age of sixteen, Horace first enlisted in the Florida National Guard Service Company, 124th Infantry Regiment.17 Prior to the Second World War, his unit participated in a number of important training and aid exercises around the southeast. For example, in 1938, they completed practice maneuvers at DeSoto National Forest in Mississippi, which aimed to simulate warfare scenarios and test the unit’s combat readiness.18 Additionally, they responded to a riot at a Tallahassee jail in 1937, and provided hurricane relief in Islamorada and Key West, FL throughout the late 1930s.19 In November 1940, as the war in Europe continued, President Franklin D. Roosevelt federalized Florida’s National Guard, calling them to active duty.20 Horace’s regiment mobilized into the US Army on November 25, 1940, several months following the fall of France to German occupation, and over a year before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.21

Once federalized, the US Army attached the 124th Infantry Regiment to the 31st Infantry Division (ID). In December 1940, the 31st ID and its subordinate units formed up at Camp Blanding, located in Starke, FL. Once its units formed and finished initial training, the 31st ID departed for Louisiana on August 4, 1941. The division spent two months in Louisiana, where it conducted unit-level training and maneuvers. After a brief return to Camp Blanding in early October, the 31st ID participated in the First Army Carolina Maneuvers in late October 1941. These training exercises, held in North Carolina as the war in Europe intensified, evaluated US preparedness for war if the nation did join the conflict overseas.22 Horace, along with the other soldiers of the 124th Infantry Regiment, returned to Camp Blanding on Dec 2.23 Then, on December 15, 1941, exactly one week after President Roosevelt asked Congress to declare war on Japan, the 124th Infantry detached from the 31st ID.24

The 124th Infantry Regiment moved up to Fort Benning (present-day Fort Moore), GA in January 1942 and joined the base’s Infantry School. In July 1942, the 124th shifted over to Fort Benning’s Replacement & School Command.25 The US Army used commands like these to assign replacement soldiers to units preparing to deploy overseas. Sometime after September 7, 1942, Horace transferred to the newly activated 119th Infantry Regiment. For Horace, this also meant a return to Camp Blanding, in his home state of Florida, as the unit moved there on October 4 as part of the 30th Infantry Division.26 The division remained at Camp Blanding until May 1943, when it departed for Tennessee. While there, the 30th ID participated in the Second Army Number 3 Tennessee Maneuvers. Instead of returning to Camp Blanding following these exercises, the division departed Tennessee for Indiana and remained there until January 1944. On January 31, the 30th ID arrived in Massachusetts, where it awaited departure for Europe.27

The US Army Transport Brazil departed Boston Harbor with the 119th Infantry Regiment aboard on February 12, 1944, and landed in Liverpool, England on February 23, 1944.28 Adams and the rest of the Regiment arrived on June 10, 1944, four days after the initial landings on Omaha Beach, Normandy.29 As Allied Forces pushed deeper into France, the 119th, not yet ready for a main assault, performed holding actions in support of larger 30th ID maneuvers.30 Between July 7 and July 19, 1944, Horace and the 119th Infantry took part in the battle for Saint-Lô, also known as the Battle of the Hedgerows, in Normandy, France.31 This effort also served as preliminary engagement for the build-up to Operation Cobra, the Allied attempt to break through German lines at Saint-Lô in their push to liberate Paris and northern France.32 During these small unit actions in July, Horace H. Adams Jr. lost his life. On July 20, 1944, Horace entered a US Army hospital where doctors pronounced him killed in the line of duty.33 Horace had achieved the rank of sergeant by the time of his death.34

Legacy

After Horace’s death, the 119th Infantry Regiment secured positions along the Vire River, in northern France, as part of Operation Cobra, which officially began on July 24, 1944. By early August, the 119th had broken through the Normandy peninsula, effectively ending the Normandy Campaign of World War II, which had begun with the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944.35 In early September, they crossed the Seine River and began an offensive push toward Brussels, making them one of the first American divisions to enter Belgium and Holland.36 The 119th Regiment remained heavily involved in the fighting along the Rhine, weathering the German counterattack at the Battle of the Bulge before taking part in the assault across the Rhine River in March of 1945.37 They remained in Europe through VE Day, May 8, 1945, nearly ten months after Horace’s death. The 119th Infantry Regiment returned to Ft. Jackson, SC on August 24, 1945 and inactivated on November 25, 1945.38

After his death in Hebecrevon, Departement de la Manche, Basse-Normandie, France, Horace’s comrades buried his remains in the Blosville-Carentan Cemetery, a temporary cemetery established for fallen American servicemen in 1944.39 The cemetery closed in 1948, and the nearly 6,000 American soldiers buried there were either reburied in what became the Normandy American Cemetery, now controlled by the American Battle Monuments Commission, or repatriated to the US.40 As part of the Return of World War II Dead program, Horace’s family requested that his remains be brought back to the US, so he could be reinterred closer to home.41 In 1948, Horace’s remains traveled back across the Atlantic Ocean aboard the United States Army Transport Greenville Victory.42 His loved ones laid him to rest at St. Augustine National Cemetery on September 9, 1948, in Section D, Plot 143.43 Along with his military burial, Horace received a Purple Heart for paying the ultimate sacrifice for his country.44

Horace’s immediate family members continued to live in or near St. Augustine, FL. His widow, Nellie Wheeler Adams, lived with her mother in St. Augustine in 1950.45 His daughter Nicey attended Ketterlinus High School in St. Augustine, FL throughout the early 1950s, graduating in 1955, seen here.46 Though Horace’s father died in 1933, when Horace was a teenager, his mother Omy Louise lived with her mother, Kate, and her son, Lawrence, in St. Augustine in 1950.47 Omy Louise passed away on June 21, 1950, at the age of sixty-four, and now rests in Evergreen Cemetery in St. Augustine, FL.48

Horace’s eldest sibling Carmen married James William Taylor, a cigar wrapper from St. Johns County, the same year Horace was born in 1919. The couple had seven children.49 Carmen passed away in 1995 at the age of ninety-three in St. Augustine, FL.50 Horace’s twin brother, Lonnie, also joined the Florida National Guard, and mobilized to the Army on the same day as Horace, November 25, 1940.51 Lonnie survived the war, and after spending some time in an Army hospital at Camp Ellis, IL, for illness, was discharged from the military in August 1945.52 He later moved to Columbus, GA with his wife, Mary Margaret Dilsaver, and daughter, Janice.53 In the decades after World War II, he owned two grocery stores in Columbus, and in 1950 worked sixty-six hours per week to operate these two establishments.54 Lonnie died in 1979, aged 60, and now rests in Parkhill Cemetery in Columbus, GA.55

Endnotes

1 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Horace Adams, St Augustine, FL.

2 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Horace Howard Adams, St Johns County, FL.

3 “U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Omy Louise Adams.

4 “Florida Marriages, 1901", Family Search (Familysearch.org: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Omy L. Smiths, St Johns County, FL.

5 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Horace H Adams, St Johns County, FL.

6 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Horace H Adams, St Johns County, FL; “1930 United States Federal Census,” entry for Horace Adams.

7 “Introduction: School of Forest, Fisheries, & Geomatics Sciences,” University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, accessed June 7, 2024, https://ffgs.ifas.ufl.edu/about/forests/history/.

8 “1930 United States Federal Census,” entry for Horace Adams.

9 “The Great Depression in Florida,” Florida Department of State, accessed March 31, 2024,

https://dos.fl.gov/florida-facts/florida-history/a-brief-history/the-great-depression-in-florida/.

10 “Florida, Death Certificate 1933,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Horace Adams, St Augustine, FL.

11 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Horace Adams, St Augustine, FL.

12 “The Works Progress Administration,” PBS: American Experience, accessed June 7, 2024, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/surviving-the-dust-bowl-works-progress-administration-wpa/.

13 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Nicey Adams, St Augustine, FL.

14 “1938 Divorce Record,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Horace Adams, St Augustine, FL.

15 “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for Nicey Adams.

16 “Florida Marriages, 1942,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.org: accessed May 9 2024), entry for Horace Adams and Corine Wheeler, Clay County, FL.

17 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide: Preliminary Abridged Edition (St. Augustine, FL: St. Francis Barracks Special Archives, 1989), 219, https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00047708/00001/images/219.

18 “3rd Army War Maneuvers Medal,” Mississippi Armed Forces Museum, accessed June 6, 2024, https://msarmedforcesmuseum.org/collection/3rd-army-war-maneuvers-medal/.

19 Florida Department of Military Affairs, Special Archives Publication Number 102: Florida National Guard Summary Unit Histories, 1880-1940 (St. Augustine, FL: St. Francis Barracks Special Archives, 1991), 62, https://original-ufdc.uflib.ufl.edu/UF00047672/00001/65j.

20 Florida Department of Military Affairs, Special Archives Publication Number 102: Florida National Guard Summary Unit Histories, 1880-1940, 62.

21 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide, 219.

22 Shelby Stanton, Order of Battle U.S. Army, World War II (Novato: Presidio Press, 1984), 110; Christopher R. Gabel, The U.S. Army GHQ Maneuvers of 1941 (Washington: United States Army Center of Military History, 1992), iii.

23 Stanton, Order of Battle, 110.

24 Stanton, Order of Battle, 220.

25 Stanton, Order of Battle, 220.

26 Stanton, Order of Battle, 219.

27 Stanton, Order of Battle, 108.

28 The 119th Infantry Regiment, Combat History of the 119th Infantry Regiment, World War Regimental Histories (Baton Rouge: Army & Navy Publishing Company, 1946), 9.

29 Stanton, Order of Battle, 109.

30 The 119th Infantry Regiment, Combat History of the 119th Infantry Regiment, 13.

31 Historical Division, St-Lo (7 July - 19 July 1944), World War II 50th Anniversary Commemorative Edition, American Forces in Action Series (Washington D. C.: War Department, 1994), 42.

32 “D-Day and the Normandy Campaign,” National WWII Museum, New Orleans, accessed June 7, 2024, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/topics/d-day-and-normandy-campaign#:~:text=On%20July%2024%E2%80%9325%2C%20American,liberate%20northern%20France%20and%20Paris.

33 “U.S., World War II Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 6, 2024), entry for Horace H Adams.

34 Department of Military Affairs. St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide, 219.

35 “D-Day and the Normandy Campaign,” National WWII Museum, New Orleans.

36 The 119th Infantry Regiment, Combat History of the 119th Infantry Regiment, 48-49.

37 The 119th Infantry Regiment, Combat History of the 119th Infantry Regiment, 93.

38 Stanton, Order of Battle, 108.

39 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1942-1954,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed January 13, 2024), entry for Horace H Adams.

40 “Blosville Temporary Cemetery Memorial,” Traces of War, accessed June 7, 2024, https://www.tracesofwar.com/sights/133238/Blosville-Temporary-Cemetery-Memorial.htm; “Normandy American Cemetery,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed June 7, 2024, https://www.abmc.gov/normandy.

41 “America’s World War II Burial Program,” US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration, accessed June 7, 2024, https://www.cem.va.gov/docs/wcag/history/WWII-Burial-Program-America.pdf, 4-5.

42 “41 Florida War Dead On Way Back,” Miami Herald, June 27, 1948, 8.

43 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1942-1954,” entry for Horace H Adams.

44 “Horace H. Adams: World War II Gold Star Veteran from Florida,” Honor States, accessed June 4, 2024, https://www.honorstates.org/profiles/445563/.

45 “1950 United States Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Nellie Wheeler, St Augustine, FL.

46 “U.S., School yearbooks, 1952,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Nicey Adams, St Augustine, FL.

47 “1950 United States Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Omy Adams, St Augustine, FL.

48 “Florida Death Index, 1950," database, Family Search (familysearch.org: accessed April 25, 2024, Omy Louise Adams, St. Augustine, FL.

49 “Florida Marriages, 1919", database, Family Search (familysearch.org: accessed May 11, 2024), Carmen Genette Adams in entry for James William Taylor, St. Augustine, FL; “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for James W Taylor, St. Johns County, FL.

50 "Florida Death Index, 1995," database, Family Search (familysearch.org: accessed 25 April 2024), entry for Carmen Adams, St. Augustine, FL.

51 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Lonnie L Adams.

52 “U.S., World War II Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Lonnie Adams.

53 “Mary Margaret Adams,” Ledger-Enquirer (Columbus, GA), December 1, 2002.

54 “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed May 10, 2024), entry for Lonnie Adams, St Augustine, FL.

55 “Lonnie Adams,” Columbus Ledger (Columbus, GA), October 2, 1979.

© 2024, University of Central Florida