Thomas Charles Oesterreicher (March 29, 1922 – June 15, 1945)

Company E, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division

by Ray Fullard and Jim Stoddard

Early Life

Thomas Charles Oesterreicher was born March 29, 1922 to Jacob P. (1883) and Vonnie (1896; née Stratton) Oesterreicher.1 Thomas, who came from a Jewish family, had two older brothers, Jacob Drayton (1914) and Desmond Dominion (1916).2 In 1920, shortly before Thomas was born, the Oesterreicher family lived and worked on a farm they owned located on Durbin-Palm Valley Rd. in the city of Palm Valley, St. Johns County, FL.3 Palm Valley, previously named Diego Plains after eighteenth-century Spanish colonizer Don Diego Espinoza, sits just north of St. Augustine, FL. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Diego Plains maintained an agricultural economy based on cattle, farming, and logging. In 1908, dredging crews dug a canal through the town, which connected the San Pablo River to the north and the Tolomato River to the south. This provided easier water access to the town’s residents, which allowed the area’s population to grow and offered farming families like the Oesterreichers better financial prospects. Because of the significant number of palm trees which grew in the area, the fronds of which residents of Diego Plains picked and sold to nearby religious groups for Palm Sunday ceremonies, residents renamed the town Palm Valley before 1920.4 Thomas Oesterreicher’s parents and older siblings lived through these changes to their town.

In 1933, Thomas’ parents, Jacob and Vonnie, divorced.5 Though both parents remained in FL, they did not live in the same area. This must have been difficult for Thomas, who was only eleven years old at the time. He and his older siblings continued to live with their mother, Vonnie, in Palm Valley. In 1935, Vonnie owned the home she now headed, located outside the city limits of Palm Valley. A woman-headed, home-owning family was rare in the early twentieth century, and in the middle of the Great Depression, it was quite a feat for Vonnie and her boys. It appears that Jacob Drayton’s and Desmond Dominion’s work in the farming industry helped their mother to maintain the family’s independence and allowed Thomas, only thirteen, to attend school.6

By 1940, Thomas’ father, Jacob, owned a citrus grove in the city of Mims, Brevard County, FL, where he lived with his new wife Ruth and four children.7 Though citrus production in Florida had waned throughout the Great Depression, the industry strengthened considerably throughout the 1940s. After the US joined World War II in 1941, the federal government appropriated supplies of processed citrus products for troops overseas. This guaranteed that citrus growers like Thomas’ father received good prices and enjoyed a stable market for their fruit.8

In 1938, Thomas’ mother Vonnie married Stanley Edward DeGrove, a farmer from St. Johns County, FL.9 In 1940, Thomas lived with his mother and stepfather in Palm Valley, FL.10 Typical of the time, Thomas only attended school until the seventh grade, and by 1940 worked as a farm laborer to help support the family.11 During the Great Depression, only about thirty percent of American teenagers graduated from high school.12 In December 1942, Stanley, who was only ten years older than Thomas, enlisted in the US Army at Camp Blanding, FL. He served as a corporal in World War II, which meant that Vonnie kept house and home together while both her husband and her youngest son fought in the war.13 Stanley returned to the US in March 1946.14

Military Life

In January 1942, Thomas C. Oesterreicher enlisted in the United States Marine Corps in Orlando, FL.15 All new accessions received basic training at one of two Marine Corps Recruit Depots, Parris Island, SC or San Diego, CA. During this phase of World War II, Marine Corps Basic Training lasted six weeks. Training included drill, military indoctrination, interior guard, bayonet training, inspections, and field training. To maintain fighting strength in its divisions, the Marine Corps implemented replacement training for new Marines. Replacement training emphasized the current needs in the war effort.16 After recruit training, Thomas reported for replacement training at Service Battalion, Marine Barracks Quantico, Virginia in April 1942. Thomas then began training as a boat operator.17 Many Marines received this training during World War II, to ensure sufficiently trained personnel to operate the boats that moved Marines and equipment ashore from Navy ships.18 In October of 1942, Thomas received further training on picket boats, which defended coastal areas and transported Marines. During that same month, Thomas was assigned to Quantico’s Post Service Battalion.19 Thomas likely suffered an injury or fell sick in January 1943, as he spent time in the Naval Hospital at Quantico.20 As a member of the Post Service Battalion, Thomas worked at Quantico’s boat docks as a boat operator, mechanic, and engineer.21 By January 1944, Thomas earned a promotion to the rank of corporal and gained the additional duty of a boat coxswain.22 Sometime between 1942 and 1944, while stationed at Quantico, Thomas met and married Betty C. Lewis, of Baltimore, MD.23

In early 1945, Thomas finished his tour of duty at Quantico. In April of that year, he was assigned to the 54th Replacement Draft and sent to the Pacific Theater.24 During World War II, the Marine Corps deployed replacement drafts to refill the ranks of forward divisions. For Thomas and 532 other Marines in his draft, this meant joining the 1st Marine Division (MARDIV) already in combat on Okinawa.25 Thomas left the US on April 13, 1945 aboard the USS Admiral C. F. Hughes. After a brief stop at Pearl Harbor, HI, the ship arrived in Guam on April 30, 1945.26 Over the next month, Marines detached from the 54th Replacement Draft as they made their way to their permanent units. By the end of May, Thomas had joined with the 1st MARDIV on Okinawa.27 In the weeks following, he battled for the island with E Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment.28

When Thomas arrived on Okinawa, Allied troops had already been fighting Japanese forces for nearly two months. On April 1, 1945, Easter Sunday, the US had launched Operation Iceberg, a complex plan to invade and occupy Okinawa and the surrounding Ryukyu islands. Controlling these islands held strategic importance to the eventual invasion of mainland Japan. US forces considered Okinawa the last push of the Island Hopping Campaign across the Pacific.29 The Japanese, recognizing Allied plans, prepared the island with comprehensive defensive positions, including a complex tunnel network.30 They also pressed the civilian population of Okinawa into military service, which resulted in the loss of about one third of Okinawa’s pre-war population.31

Over the course of two months, throughout April and May 1945, US forces ground down Japan’s defenses. After landing on Okinawa in May 1945, the 1st Marines, along with other Marine and Army units, fought their way across the island. In late May, they led a deadly siege of the Shuri Line, a rugged and well-fortified defensive position that ran across the waist of southern Okinawa.32 By the beginning of June, the 1st Marine Regiment pulled back for refitting and adding sorely needed replacements to its lines.33 Thomas likely served as one such replacement. On June 3, 1st MARDIV ordered the 1st Marines back into the line to relieve the 5th Marines at Tsukasan, near the southeast coast of the island.34 Thomas likely joined this action as his first movement to the front.

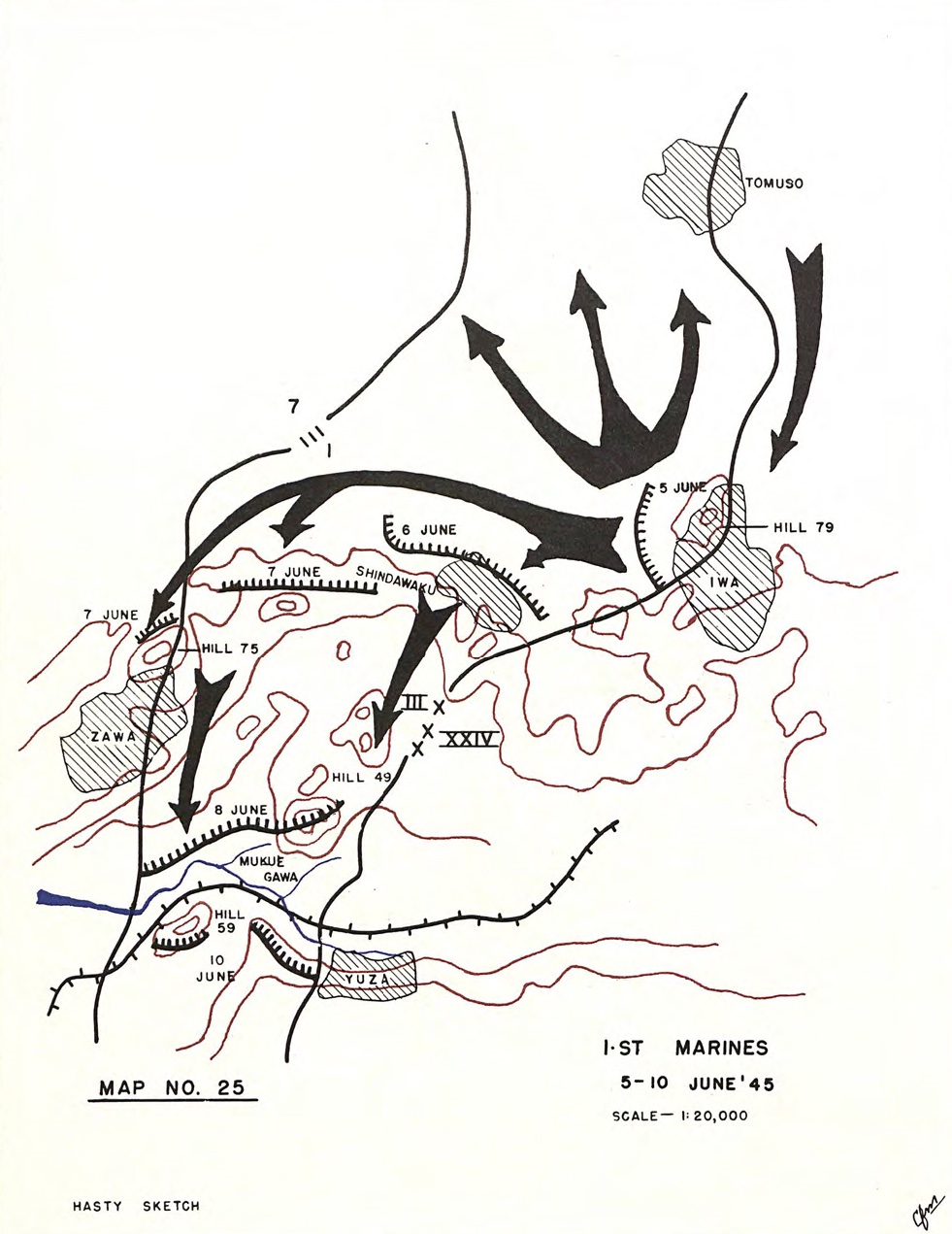

Weather and mud slowed the relief effort and, before the 1st Marines could fully mobilize, 1st MARDIV altered the regiment’s orders. The division sent new orders for the 1st Marines to take control of the elevated position between the locations of Iwa and Shindawaku, as seen on this map. As battalions, 1st Marines moved out before dawn on June 4.35 Over the next several days, Thomas and his fellow Marines fought the Japanese, the terrain, and the weather to achieve and hold their objective. On June 9, combined arms patrols tested the line in preparation for an assault the next day.36 While 3rd Battalion assaulted Yuza Hill, inland from the landing areas in the southern part of the island, Thomas’s 2nd Battalion provided them with supporting fire from nearby Hill 59. Clearing the pass between these two hills allowed the 2nd Battalion to lead tanks through it, thereby clearing out the remaining Japanese defenders. This assault carried a high toll, especially for the 3rd Battalion. Its C Company lost over forty percent of its 175 Marines.37 Similar assaults continued through the next two days.

On the night of June 11 and 12, Thomas’s E Company dug in along Yuza Ridge. In an attempt to retake the area, the Japanese used Okinawan civilians to infiltrate the American lines. When the Marines of E Company realized Japanese soldiers mixed in with the civilians, they opened fire. About twenty Japanese soldiers charged forward in a bayonet attack. Another group assaulted the rear of E Company’s position with satchel charges and rifle fire. In the confusion of this nighttime raid, E Company held its position. When they took the toll of the attempted infiltration the next morning, the Marines counted forty Japanese and five Americans among the dead.38

Over the next few days, the 1st Marines received artillery fire from areas still in Japanese control, including from an area called Kunishi Ridge, densely packed with Japanese troops.39 Thomas’s E Company led the assault on this location in the pre-dawn hours of June 14, 1945. By five a.m. that morning, they had quietly reached the peak of the ridge. Shortly thereafter, the Japanese Army noticed their presence and opened fire. As the battle intensified, the Japanese cut off E and G companies’ connections to 2nd Battalion’s headquarters. This prevented the battalion from resupplying its companies and evacuating the wounded. Eventually, Marine tanks broke through and resupplied E and G Companies. On their return trips to 2nd Battalion, the tanks carried out the wounded. F Company joined its sister companies on the ridge and pressed the assault as the tanks continued their runs into the next day.40 During the heat of battle on June 15, enemy fire mortally wounded Corporal Thomas Oesterreicher.41 A tank likely evacuated him from the front as it returned from a supply run. Later that evening, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment relieved the 1st Marines. It took US forces two more days to secure Kunishi Ridge.42

Legacy

On June 22, 1945, US forces secured Okinawa. Despite the Allied victory, the island came with a heavy price. At the battle’s end, American troops suffered 49,000 casualties, including 12,500 deaths. The Japanese Army’s death toll reached approximately 110,000, with another 100,000 civilians also perishing during the bloody battle.43 Over twenty US soldiers who served on Okinawa received the Medal of Honor, the highest US military decoration. Today, several Marine bases on the island carry the names of some of these fallen heroes, including Camps Courtney, Foster, Gonsalves, Hansen, Kinser, Lester, McTureous, and Schwab.44 Okinawa proved to be the final island the Marines assaulted in the Pacific Campaign. During preparations for the invasion of mainland Japan, President Harry S. Truman ordered two of the newly-developed atomic bombs dropped on the cities of Hiroshima, on August 6, and Nagasaki, on August 9, 1945. Less than a month later, and less than three months after Thomas died, Imperial Japan officially surrendered to Allied forces on September 2, 1945, ending combat operations in the Second World War.45

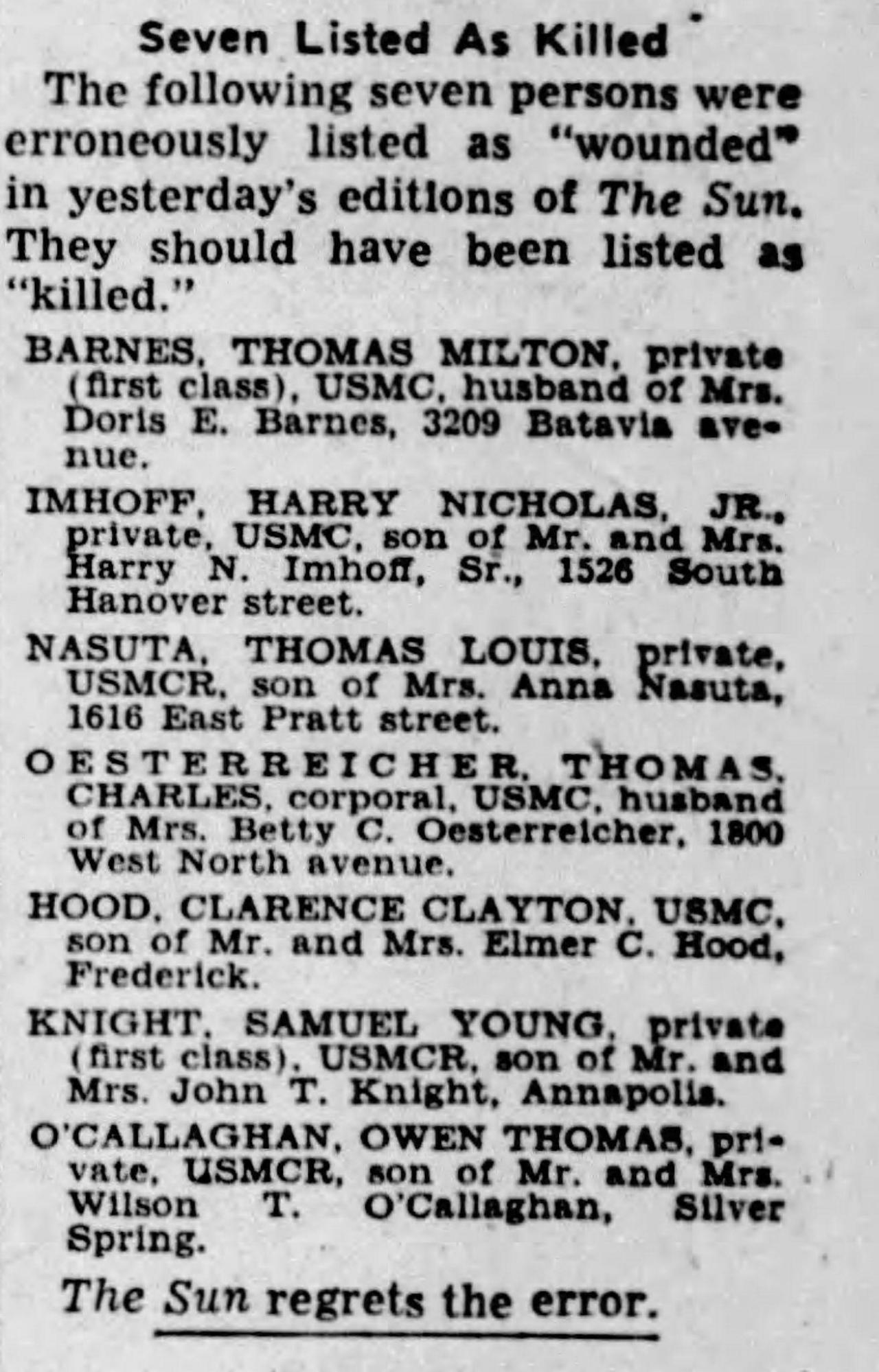

The Baltimore Sun reported Thomas as killed in action on July 25, 1945, about a month after he died.46 The US military initially interred him on Okinawa in the 1st Marine Division Cemetery in Ryukyu Retto.47 In the years after the war, Thomas’s mother and next of kin, Vonnie, chose to bring her son’s remains home to St. Johns County, where he was born.48 On April 14, 1949, Corporal Thomas Charles Oesterreicher was laid to rest in Section D, Site 89 in the St. Augustine National Cemetery.49

In 1995, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Okinawa, local political leaders on the island unveiled the Cornerstone of Peace Monument, which stands in Itoman City, near the southern coast of Okinawa. Consisting of 114 marble slabs which bear the names of those who lost their lives during the battle, the Cornerstone of Peace ensures that the sacrifices made by the many civilians, and Japanese and Allied troops throughout the spring and summer of 1945 are not forgotten. Though his remains no longer rest overseas, Thomas Oesterreicher’s name is inscribed on the monument, where his memory endures.50

Endnotes

1 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 13, 2023), entry for Thomas C. Oesterreicher; “1920 United States Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 26, 2023), entry for Vonnie Oesterreicher, St. Johns County, Florida; “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 13, 2023), entry for Thomas C. Oesterreicher, St. Johns County, FL: 1935.

2 “1920 United States Census,” Vonnie Oesterreicher; “Florida, U.S., State Census,” Thomas C. Oesterreicher; “U.S., World War II Jewish Servicemen Cards, 1942-1947,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 26, 2023), entry for Thomas Charles Oesterreicher.

3 “1920 United States Census,” Vonnie Oesterreicher.

4 “Palm Valley,” Beaches Museum, accessed June 26, 2023, https://www.beachesmuseum.org/palm-valley/.

5 On the 1935 FL State Census, Vonnie Oesterreicher reported herself as a widow, but Jacob P. Oesterreicher lived until 1964; “Florida, U.S., Divorce Index, 1927-2001,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 26, 2023), entry for Jacob P. Oesterreicher, St. Johns County, FL: 1933; “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 13, 2023), entry for Vonnnie Oesterreicher, St. Johns County, FL: 1935.

6 “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” Vonnie Oesterreicher.

7 As the youngest child listed on the 1940 US Federal Census was seven years old, it seems unlikely that these children were Jacob P.’s; Ruth provided data for the family on the census, which explains why the four children are not listed as step-children with relation to Jacob P., the head of the household; “1940 United States Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed August 14, 2023), entry for Jacob P. Oesterreicher, Brevard County, FL.

8 “The Citrus Industry in Florida,” Florida Department of State: Florida Division of Historical Resources, accessed August 16, 2023, https://dos.myflorida.com/historical/museums/historical-museums/united-connections/foodways/food-cultivation-and-economies/the-citrus-industry-in-florida/#:~:text=It%20originally%20came%20from%20southeast,the%20growth%20of%20the%20fruit.

9 “Florida, U.S., Marriage Index, 1822-1875 and 1927-2001,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 26, 2023), entry for Stanley Edwin Degrove and Vonnie Josephine Oesterreicher, St. Johns County, Florida.

10 “1940 United States Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 13, 2023), entry for Thomas Oesterreicher, St. Johns County, FL.

11 “1940 United States Census,” Thomas Oesterreicher.

12 David Leonhardt, “Students of the Great Recession,” New York Times Magazine (New York, NY), May 7, 2010, accessed June 20, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/09/magazine/09fob-wwln-t.html#:~:text=In%201930%2C%20only%2030%20percent,t%20just%20make%20Americans%20tougher.

13 “WWII Army Enlistment Records,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed August 14, 2023), entry for Stanley E. DeGrove, serial number 34537816; “CPL Stanley E. DeGove,” FindAGrave, February 26, 2010, accessed August 14, 2023, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/48831053/stanley-e-degrove?_gl=1.

14 “Troops Due at New York,” Miami Herald, March 14, 1946, 10.

15 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958, database, Ancestry, (ancestry.com: accessed June 13, 2023), entry for Thomas C. Oesterreicher, Southern Recruiting Division, Atlanta, GA.

16 Jessica Anderson-Colon, “Marine Corps Boot Camp during World War II: The Gateway to the Corps' Success at Iwo Jima,” Marine Corps History 7, no. 1 (September 14, 2021): 50, https://doi.org/10.35318/mch.2021070103.

17 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 13, 2023), entry for Thomas C. Oesterreicher, April 1942.

18 Julius Augustus Furer, “The United States Marine Corps: Origin, Legal Status, and Mission,” in Administration of the Navy Department in World War II (Washington, D.C.:U.S. Government Printing Office, 1960), 550, https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USN/Admin-Hist/USN-Admin/USN-Admin-14.html.

19 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 13, 2023), entry for Thomas C. Oesterreicher, October 1942.

20 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 13, 2023), entry for Thomas C. Oesterreicher, January 1943.

21 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 13, 2023), entry for Thomas C. Oesterreicher, January 1944.

22 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958,” Thomas C. Oesterreicher, January 1944.

23 “U.S., Marine Corps Casualty Index, 1940-1958,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 26, 2023), entry for Thomas Charles Oesterreicher, June 15, 1945; “U.S., World War II Jewish Servicemen Cards, 1942-1947,” Thomas Charles Oesterreicher.

24 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798-1958,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 26, 2023) entry for Thomas C. Oesterreicher, April 1945.

25 James R. Stockman, The First Marine Division on Okinawa: 1 April - 30 June 1945 (Quantico: Historical Division Headquarters Marine Corps, 1967), 9-a.

26 “U.S., Marine Corps Muster Rolls,” April 1945.

27 Stockman, The First Marine Division on Okinawa, 9-a.

28 “U.S., Marine Corps Casualty Index, 1940-1958,” Thomas Charles Oesterreicher.

29 “Battle of Okinawa: 1 April - 23 June 1945,” Naval History and Heritage Command, 2022, accessed August 14, 2023, https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1945/battle-of-okinawa.html.

30 “Battle of Okinawa,” The National WWII Museum: New Orleans, May 20, 2020, accessed August 14, 2023, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/topics/battle-of-okinawa.

31 “Okinawa: The Costs of Victory in the Last Battle,” The National WWII Museum: New Orleans, July 7, 2022, accessed August 14, 2023, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/okinawa-costs-victory-last-battle.

32 Joseph H. Alexander, “The Final Campaign: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa (Assault on Shuri),” Marines in World War II Commemorative Series, accessed July 3, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/npswapa/extcontent/usmc/pcn-190-003135-00/sec5a.htm.

33 Stockman, The First Marine Division on Okinawa, 45.

34 Stockman, The First Marine Division on Okinawa, 46. The publisher did not include numbers on pages with maps. The above map was printed on the page before page 48.

35 Stockman, The First Marine Division on Okinawa, 46.

36 Combined arms patrols are small unit movements that add mechanized elements; Stockman, The First Marine Division on Okinawa, 48.

37 Stockman, The First Marine Division on Okinawa, 48.

38 Unfortunately, the official history does not distinguish how many Okinawan civilians were among the forty Japanese dead; Stockman, The First Marine Division on Okinawa, 50.

39 Stockman, The First Marine Division on Okinawa, 51.

40 Stockman, The First Marine Division on Okinawa, 52.

41 “U.S., Marine Corps Casualty Index, 1940-1958,” Thomas Charles Oesterreicher; Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide: Preliminary Abridged Edition (St. Augustine, FL: St. Francis Barracks Special Archives, 1989), 204.

42 Stockman, The First Marine Division on Okinawa, 57.

43 “Battle of Okinawa.”

44 Jovane M. Henry, “Okinawa Bases Named for Fallen Heroes,” Marine Corps Installations Pacific, 2011, https://www.mcipac.marines.mil/News/Article/531402/okinawa-bases-named-for-fallen-heroes/https%3A%2F%2Fwww.mcipac.marines.mil%2FNews%2FArticle%2F531402%2Fokinawa-bases-named-for-fallen-heroes%2F.

45 “Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki: 1945,” The National Museum of Nuclear Science and History,” June 5, 2014, accessed August 14, 2023, https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/history/bombings-hiroshima-and-nagasaki-1945/.

46 “Seven Listed as Killed,” Baltimore Sun, July 25, 1945, 24.

47 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” Thomas C. Oesterreicher.

48 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” Thomas C. Oesterreicher.

49 “U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” Thomas C. Oesterreicher.

50 “Cornerstone of Peace,” Okinawa Karate Navi, accessed August 17, 2023, https://okinawa-karate-navi.com/en/spot/detail/44/.

© 2023, University of Central Florida