Charles Hudson Whidden (December 25, 1925-April 30, 1945)

Company A, 347th Infantry Regiment, 87th Division, US Army

By Kimberly Escobar and Aaron Connors

Early Life

Charles Hudson Whidden, known as Charlie, was born in Palmetto, FL on December 25, 1925 to Ronnie and Bertie (née Rich) Whidden.1 At the time, the Whiddens had a strong foundation in Florida, extending back at least to the mid nineteenth century.2 John Whidden, Charlie’s great grandfather, was born on February 6, 1839 in Columbia County, FL, and served in both the Third Seminole War and the Civil War. During the Third Seminole War, he mustered into Captain F. M. Durrance’s Florida Mounted Volunteers on December 29, 1855, and mustered out in August 1856.3 He later rejoined the military during the Civil War, and served as a Corporal with the 7th Florida Infantry of the Confederate Army.4 Following the war, John married his wife, Arminda Roberts, and settled in Polk County, FL, where they took up farming. The couple had seven children.5 John died on March 13, 1926 at the age of 87.6 His family laid him to rest at Collins Cemetery on Cumbee Road, in Lakeland, FL. In 1970, John Whidden’s great-great granddaughter, Lana T. Mahoney, applied to place a Veterans marker atop his grave to memorialize him and his military service. The US government granted this request in 1972.7

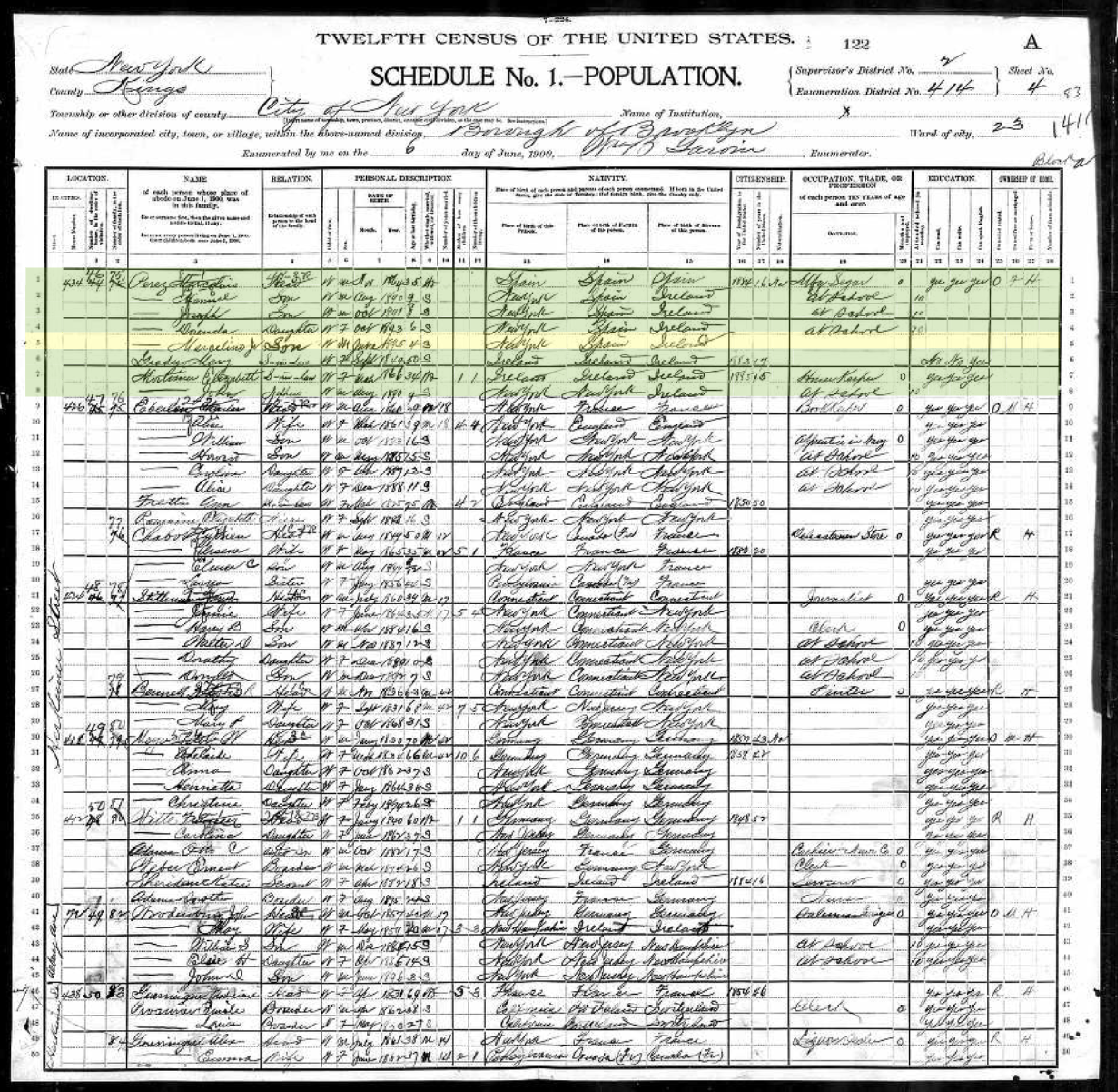

Charlie shared a name with his grandfather, Charles Leroy.8 Charles Leroy Whidden became the first-born son of Arminda and John, welcomed by the couple on March 13, 1868.9 Charles Leroy married Lillie O. Yeomans on October 13, 1889.10 They had five children: Roy, Ronnie, Lela Cassie, George, and Paul.11 By 1900, Charles Leroy worked as a daytime laborer in a rented home in Manatee County, FL. By 1917, he had moved to Lakeland, FL and worked as a fireman.12 Charles Leroy died, aged 55, in 1920, five years before the birth of his grandson Charlie.13 Lillie died, aged 56, on October 1, 1931.14

Ronnie, Charlie’s father, was born February 28, 1895, in Sarasota FL, where he grew up with three brothers, Roy, George, and Paul, and one sister, Cassey.15 In 1910, at the age of fifteen, Ronnie had joined the workforce as a laborer in a saw mill alongside his father and older brother, Roy.16 On September 5, 1917, five months after the US entered the First World War, Ronnie registered for the draft, though he never served.17 At that time, he worked in a cemetery.18 In 1920, Ronnie continued to live at home with his parents and siblings, and worked as a carpenter for a phosphate mill.19 Sometime before 1925, Ronnie married Bertie Mae Rich, and settled in Manatee County, FL, where they welcomed their first son, Charles Hudson, in December 1925. The couple had nine more children after Charlie, including Bertie Lee (1926), Beulah Mae (1928), Josephine (1929), Jeremiah (1931), Barbara (1934), twins Margie and Margaret (1938), Patricia (1940), and Samuel (1944).20 In 1935, Ronnie worked at a truck farm, growing produce to sell at local markets, and lived in a rented home with Bertie Mae and their children.21 By 1940, Ronnie had changed careers and worked as a machinist at a crate manufacturing company.22

Charlie grew up during difficult times in Florida. While the Great Depression did not begin until the stock market collapsed in October 1929, additional economic hardships affected Florida before the rest of the nation and the world. Although Florida experienced a land boom in the early 1920s, largely driven by land developers looking to capitalize on movement and tourism to the state, Florida’s economy began declining mid-decade.23 The Great Miami Hurricane in 1926 and the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane, which together caused around $125 million in damages, hurt the state’s economy.24 Additionally, in 1929, an infestation of Mediterranean fruit flies damaged the previously-growing citrus industry, reducing production by up to sixty percent of pre-Depression levels.25 Charlie attended grammar school during the Depression years, but he did not attend high school.26 In 1930, only about thirty percent of American teenagers graduated high school.27 Many school-age children and teens during this period instead contributed their labor to help their families financially. In 1940, at age fifteen, Charlie labored as an unpaid family worker, meaning that he contributed to the family’s livelihood by working outside of the home without pay—possibly with his father at the crate manufacturing company.28

On December 22, 1943, Charlie registered for the Selective Service. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Selective Training and Service Act into law on September 16, 1940, instituting the first peacetime draft in US history. Over the next five years, approximately fifty million men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five registered, and the War Department called on ten million to serve in the military.29 At the time, Charlie was unemployed. He stood five feet, nine inches tall, and had brown hair and brown eyes, as indicated on the back of his draft card.30

Military Service

On March 24, 1944, Charlie joined the US Army at Camp Blanding, near Starke, FL.31 Following US entry into World War II, Florida grew rapidly from a sparsely-populated rural and agricultural state into a major source of land and materials for the war effort. As a peninsula, Florida became an ideal place to train soldiers for amphibious landings and waterfront operations. By the time Charlie arrived at Camp Blanding in 1944, which had become an Infantry Replacement Training Center, the area around the base had ballooned in population. Approximately 800,000 soldiers trained at Camp Blanding during the war, and it held over four thousand German prisoners of war.32

Following his training at Camp Blanding, Charlie joined Company A of the 347th Infantry Regiment, 87th Infantry Division (ID).33 First organized in Arkansas during World War I, the 87th ID’s unit emblem of a golden acorn remains a symbol of Arkansas’s oak trees. The 87th ID saw no combat in World War I, as the armistice occurred before they could deploy overseas.34 The US military later reactivated the division on December 12, 1942. Charlie deployed overseas with the division in October 1944 for additional training in the UK. In early December, 1944, the 87th ID shipped out to the city of Metz, in eastern France, and on December 8 saw action at Fort Driant, a German defensive position along the Moselle River. Charlie and the 87th continued their advance east toward Germany, and captured the French cities of Rimling, Obergailbach, and Guiderkirch, near the Vosges Mountains along the Franco-German border, in mid-December. The Army placed the 87th ID in reserve for much needed rest on December 24. Five days later, the 87th traveled north to Belgium, where they participated in the Second Battle of the Ardennes, the massive and final German offensive attack, better known in the US as the Battle of the Bulge.35

The Battle of the Bulge began December 16, 1944 and lasted until January 25, 1945. Fought in freezing cold conditions throughout the winter, the battle began with a desperate German push through the Ardennes Forest between Belgium and Luxembourg, believed to be an impenetrable landscape. The Germans hoped to move through the underprotected area and split the Allied forces in two before they reached the German border, then encircle the remnants to defeat them.36 Instead, the Allies fought hard in freezing winter weather to prevent Germany’s final push. The 1st Battalion of the 347th Regiment, including Charlie and his Company A comrades, captured the region of Remagne, in southern Belgium, on New Years Day 1945.37 Charlie and his fellow troops endured heavy mortar fire from the German and felt fire support from tanks of the 761st Tank Battalion, known as the Black Panthers, a notable African American unit.38 The First Battalion captured Germont, France on January 2, 1945, which helped to cut off the German avenue of escape back east.39

On January 17, 1945, the 87th ID moved into Luxembourg to relieve the 4th ID along the Sauer river, between Echtermach and Wasserbilig.40 The 347th Regiment took the palace of the 4th ID’s 22nd Regiment. Charlie’s 1st Battalion relieved the forces of the 22nd’s 2nd Battalion. Over the following days, his battalion patrolled the area and secured German prisoners. The 87th ID then moved to capture Wasserbilig, in eastern Luxembourg, on January 23, during the closing days of the Battle of the Bulge. Following the battle, the 87th ID relieved elements of the 18th Airborne Corps near the Belgian city of St. Vith, on the Luxembourg border, while under heavy machine gun fire.41

Charlie suffered an injury on February 5, 1945, while the 87th ID remained in Belgium. After a fall, he sustained a laceration to his knee that required medical attention.42 He received care and recuperated at a field hospital for a short time before rejoining his unit.43 The 87th ID remained in defensive positions in Belgium until February 26, 1945, when they attacked Ormont and Hallschlag, border towns in western Germany. As they approached these towns, the 87th confronted trenches, barbed wire, concrete pillboxes, and ‘dragon’s teeth’--pyramids designed to prevent tanks driving over them. The 347th captured Ormont on March 1.44

Elements of the 87th crossed the Kyll River on March 6 and the Moselle River on March 16.45 Charlie and the 1st Battalion crossed the Moselle near Winningen, while the 3rd Battalion crossed near Kobern. The 1st Battalion then occupied Rhens, Germany, on the west bank of the Rhine River, by the end of March 1945. Charlie and his comrades then prepared to cross the Rhine River on their push farther east. On March 25, the 1st Battalion assaulted the east bank of the Rhine under heavy German fire. They reached the opposite side of the river and immediately moved to take the high ground south of the city of Oberlahnstein, on the right bank. The 1st Battalion faced stiff resistance here. By the late afternoon of March 25, the men had less than five rounds of ammunition each.46 On March 26, 1945, following the crossing operation, the Army reported Charlie as Missing in Action. The War Department later stated he returned to his unit shortly after his disappearance.47

By March 27, the 87th advanced up to the Lahn River, a tributary of the Rhine River in western Germany, where it took responsibility for the area between the cities of Diez and Limburg.48 The division then tasked out its regiments. On April 7, it sent the 347th east toward the Czechoslovakian border. As the regiments of the 87th ID passed through towns on their trek east, they noticed evidence that German soldiers had deserted them just hours earlier. The machinery and industry that once hummed around the clock lay silent.49 The 87th took the resort town of Oberhof on April 7, secured the Saale River on April 12, and took the city of Plauen, in east Germany, on April 17.50 After Plauen’s capture, Charlie and his comrades of 1st Battalion, 347th Regiment moved to take the city of Oelsnitz, four miles from the Czechoslovakian border; they took it with little resistance. The 347th Regiment remained in defensive positions along the Czechoslovakian border until early May. During this defensive stand, Charles Hudson Whidden made the ultimate sacrifice for his country, and fell in battle on April 30, 1945. He was nineteen years old.51

Legacy

The soldiers of the 87th ID held their positions along the Czechoslovakian border until May 6, when they advanced one last time to take Falkenstein, in Bavaria, Germany, six days after Charlie lost his life.52 That day, approximately forty thousand German troops surrendered to the 347th Regiment. This surrender included both Wehrmacht (general land forces) and Schutzstaffel (SS, elite units), and included high-ranking German officers. The next day, May 7, 1945, German officials signed the terms of their unconditional surrender, ending most fighting in Europe. The 87th ID learned of the news that night and received orders to cease all offensive actions.53 The war ended in Europe on VE day, May 8, 1945.

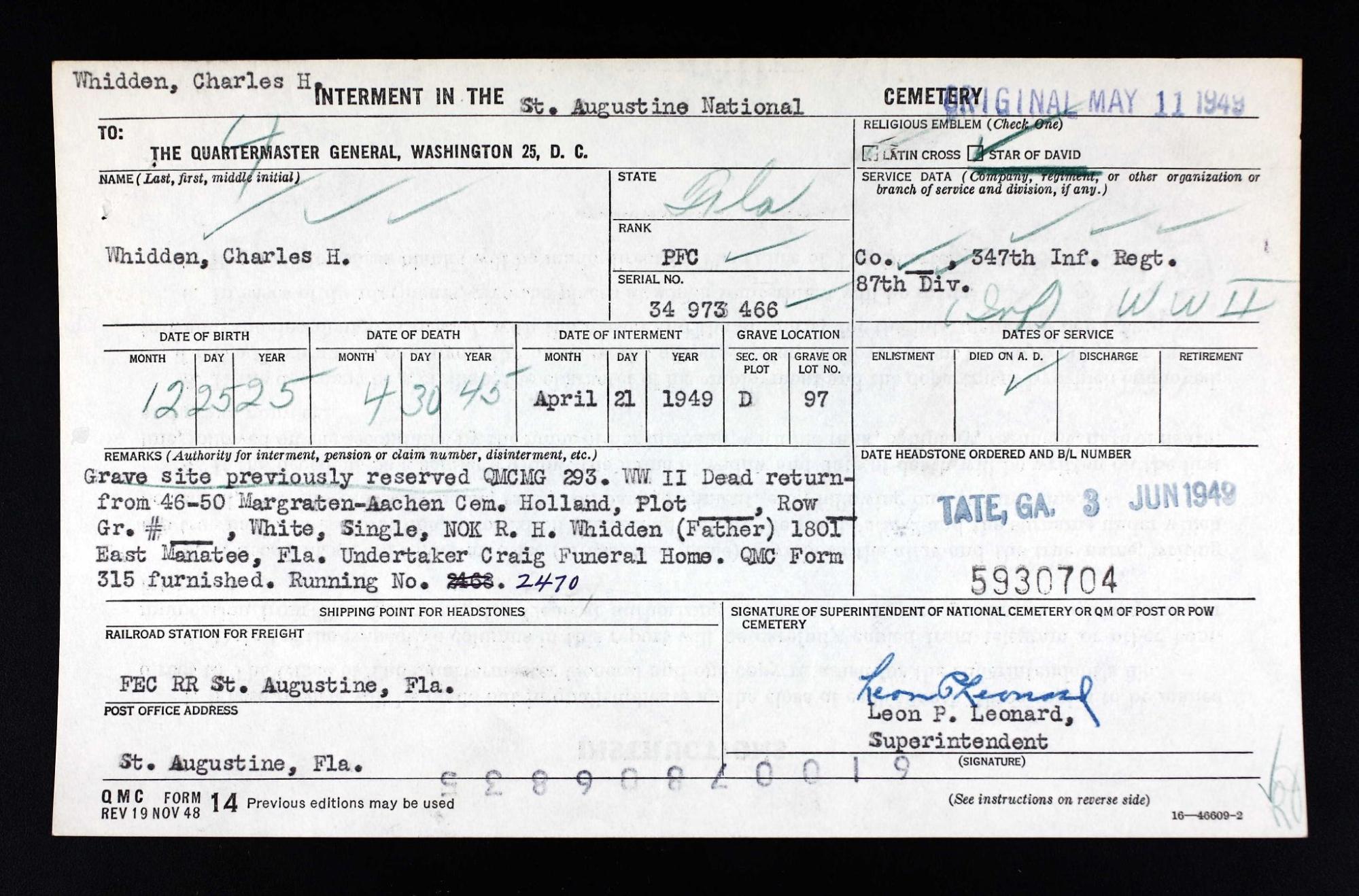

The War Department notified Charlie’s family of his death by mid-May, 1945.54 Charlie’s comrades initially buried him in Margarten-Aachen Cemetery, in Holland.55 The US 9th Army established the site as a temporary cemetery on November 10, 1944, and many of the soldiers who died during the 1945 advance into Germany were buried there.56 The site later became the American Battle Monuments Commission’s (ABMC) Netherlands American Cemetery.57 Six months after the conclusion of the war, the US Government initiated the Return of World War II Dead program, which repatriated the remains of over 171,000 service members from cemeteries abroad back to the US. The program allowed the families of Veterans killed overseas the option to bring their loved ones back to the US so they could rest closer to home. Because of the enormity and complexity of the task, some recoveries took years.58 Charlie’s father Ronnie, as his next of kin, decided to bring his son back to Florida, seen on the cemetery interment card here.59 In 1949, the USNS Haiti Victory returned Charlie’s remains along with 2,918 others killed during and after the war.60 On April 21, 1949, Charlie’s family laid him to rest at St. Augustine National Cemetery, where he remains with his fellow Veterans in section D, plot 97.61

Charlie’s memory persists in a number of significant ways. His headstone at St. Augustine National Cemetery includes an emblem of the Star of David, meaning he identified as Jewish. He remains one of over 550,000 Jewish American men and women who served during World War II.62 His legacy also endures in the 87th Infantry Division Monument in Fort Benning, GA, which honors and memorializes soldiers in the division who lost their lives during their campaigns in the Rhineland, the Ardennes-Alsace region, and Central Europe during World War II. Erected in 2013 by the 87th Infantry Division Legacy Association, the monument aims to remember the sacrifices made by those who served with the division.63

Charlie’s parents, Ronnie and Bertie, continued to work in crate manufacturing after the war. In 1950, they both worked in a crate mill alongside their daughters Beulah Mae and Josephine.64 Charlie’s younger brother, Jeremiah, followed in his brother’s footsteps and joined the military, serving as a seaman apprentice in the US Navy. He served during the Korean War on a tanker, the USS Passumpsic, which hauled oil to naval crafts stationed in the waters between Japan and Korea.65 Jeremiah continued his service through the 1960s. In 1960, he served on the destroyer USS Ault, stationed in the Mediterranean performing operational exercises at the time.66 Later in the decade, he served during the Vietnam War as an officer on a patrol craft in River Division 534, which operated along the Vam Co Dong and Vam Co Tay Rivers.67 Jeremiah served in the Navy for twenty-two years and earned the Bronze Star with gold stars. He died at the age of eighty-two, on March 16, 2014, and now rests at Forest Lawn Memorial Cemetery in Panama City, FL.68 Like his brother, Charlie, his legacy of service endures.

Endnotes

1 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 28, 2024), entry for Charles H. Whidden; “Ronnie Hudson Whidden,” FindAGrave, January 12, 2014, accessed June 30, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/123319905/ronnie_hudson_whidden; “Bertie Mae Rich Whidden,” FindAGrave, January 12, 2014, accessed June 30, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/123319861/bertie-mae-whidden.

2 “U.S. Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 3, 2024), entry for John Whiddon; “U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1861-1985”, database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 17, 2024), entry for John Whidden, Lakeland, FL.

3 “U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1861-1985,” entry for John Whidden; “Florida Soldiers in the Seminole War,” Florida Genealogy Trails, accessed June 30, 2014, http://genealogytrails.com/fla/military/seminolewarsoldiers.html.

4 “U.S. Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861-1865,” entry for John Whiddon.

5 “1880 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 20, 2024), entry for John Whidden, Polk County, FL; “John Whidden,” FindAGrave, July 12, 2008, accessed June 30, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/28232247/john_whidden.

6 Spessard Stone, “Cracker Barrel Family Histories,” RootsWeb, Accessed June 17, 2024, https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~crackerbarrel/genealogy/JohWhi.html.

7 “U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1861-1985,” entry for John Whidden, Lakeland, FL; when Lana T. Mahoney applied for John Widden’s Veteran’s marker, she cited his service in the Third Seminole War with the Florida Mounted Volunteers. The marker application makes no mention of John’s service in the Confederate 7th Florida Infantry. With specific exceptions, Confederate Veterans may not receive traditional Veteran markers, nor burials in National Cemeteries. For more information see: “History of National Cemeteries,” U.S. National Park Service, July 12, 2023, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/national-cemeteries-history.htm; “NCA History and Development,” National Cemetery Administration, October 18, 2023, https://www.cem.va.gov/facts/NCA_History_and_Development_1.asp.

8 “1900 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 3, 2024), entry for Charles Whitter, Manatee, FL.

9 “Charles Leroy Whidden,” FindAGrave, August 18, 2015, accessed June 30, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/150923915/charles-leroy-whidden.

10 “Florida, U.S., County Marriage Records, 1823-1982,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 3, 2024), entry for C L Whidden, Polk County, FL.

11 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 17, 2024), entry for Roney Whidden, Medulla, FL.

12 “1900 United States Federal Census,” Ancestry, Charles Whitter.; “U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 20, 2024), entry for Charles L Whidden, Lakeland, FL, 1917.

13 “Florida, U.S., Death Index, 1877-1998,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 20, 2024, entry for Charles Leroy Whidden, Polk County, FL.

14 “Mrs. Whidden Passes Away On Thursday Night,” Bradenton Herald, October 2, 1931.

15 “1910 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 3, 2024), entry for Roney Whidden, Polk County, FL; “1920 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 3, 2024), entry for Rhoney Whidden, Polk County, FL; “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 17, 2024), entry for Ronie Hudson Whidden, Lakeland, FL.

16 “1910 United States Federal Census,” entry for Roney Whidden.

17 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” entry for Ronie Hudson Whidden; “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 17, 2024), entry for Charlie H Whidden, Manatee County, FL.

18 “U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” entry for Ronie Hudson Whidden.

19 “1920 United States Federal Census,” entry for Rhonie Whidden; “1930 United States Federal Census,” entry for Charlie H Whidden.

20 “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 20, 2024), entry for Ronnie H Whidden, Manatee, FL; “1950 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 20, 2024), entry for Ronnie H Whidden, Manatee County, FL.

21 “1930 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 17, 2024), entry for Charlie H Whidden, Manatee County, FL; “Florida, U.S., State Census, 1867-1945,” entry for Ronnie H Whidden, Manatee, FL.

22 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 20, 2024), entry for Charles H Whidden, Manatee County, FL.

23 “The Great Depression in Florida”, Florida Department of State, accessed June 17, 2024, https://dos.fl.gov/florida-facts/florida-history/a-brief-history/the-great-depression-in-florida/.

24 “Hurricane of September 20th, 1926,” National Weather Service, accessed June 20, 2024, https://www.weather.gov/mob/1926Hurricane; “Memorial Web Page for the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane,” National Weather Service, accessed June 20, 2024, https://www.weather.gov/mfl/okeechobee.

25 “The Great Depression in Florida”, Florida Department of State.

26 “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for Charles H Whidden; “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed June 17, 2024), entry for Charlie H Whidden, Manatee County, FL.

27 David Leonhardt, “Students of the Great Recession,” New York Times Magazine (New York, NY), May 7, 2010, accessed June 30, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/09/magazine/09fob-wwln-t.html.

28 “1940 United States Federal Census,” entry for Charles H Whidden.

29 “Research Starters: The Draft and World War II,” The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, accessed June 30, 2024, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/students-teachers/student-resources/research-starters/draft-and-wwii#:~:text=The%20Draft%20and%20WWII,draft%20in%20United%20States'%20history.

30 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed July 1, 2024), entry for Charley Hudson Whidden, Manatee, FL.

31 “U.S., World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946,” entry for Charlie H Whidden.

32 “Florida During World War II,” National Park Service, April 28, 2020, accessed June 17, 2024, https://www.nps.gov/casa/learn/historyculture/florida-in-world-war-ii.htm; George E. Cressman Jr., “Camp Blanding in World War II: The Early Years,” Florida Historical Quarterly 97, no. 1 (2018), 36.

33 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for Charles H. Whidden.

34 87th Infantry Division Association, “347th Infantry Regiment,” in An Historical and Pictorial Record of the 87th Infantry Division in World War II, 1942-1945 (self-pub., 87th Infantry Division, 1988), 53, https://87thinfantrydivision.com/87thMedia/Publications/History-Book/04_347thInfantry.pdf.

35 “87th Infantry Division - Golden Acorn,” US Army Divisions, accessed June 21, 2024, https://www.armydivs.com/87th-infantry-division.

36 “Battle of the Bulge, December 1944-January 1945,” US Army, accessed June 30, 2024, https://www.army.mil/botb/.

37 87th Division, “347th Infantry Regiment,” 169.

38 “Black Panthers in the Snow: The 761st Tank Battalion at the Battle of the Bulge,” The National WWII Museum, July 10, 2020, accessed July 16, 2024, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/black-panthers-761st-tank-battalion-battle-of-the-bulge.

39 “87th Infantry Division - Golden Acorn,” US Army Divisions; 87th Division, “347th Infantry Regiment,” 60-70.

40 Shelby L. Stanton, World War II Order Of Battle (New York: Galahad Books, 1991), 160.

41 “87th Infantry Division - Golden Acorn,” US Army Divisions; 87th Division, “347th Infantry Regiment,” 67-70.

42 While it is not clear how Charlie fell, it is worth noting the hazards of troop movements during winter conditions.

43 “U.S., WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed June 21, 2024), entry for Whidden, Charlie H; “Bradenton Revities, Wounded in Action,” Bradenton Herald, February 18, 1945, 2.

44 87th Division, “347th Infantry Regiment,” 73-80; “87th Infantry Division - Golden Acorn,” US Army Divisions; Stanton, World War II Order Of Battle, 160.

45 87th Division, “347th Infantry Regiment,” 73-80; “87th Infantry Division - Golden Acorn,” US Army Divisions; Stanton, World War II Order Of Battle, 160.

46 87th Division, “347th Infantry Regiment,” 80-87.

47 “Private Whidden Listed Missing On German Soil,” Bradenton Herald, April 22, 1945, 5; “Whidden Body Enroute Home From Europe,” Bradenton Herald, March 17, 1949, 2; Charlie likely did not receive punishment for his absence, and he returned to his unit on the same day they declared him missing. Based on this evidence, the confusion of battle remains the likely cause for his separation and quick return.

48 Stanton, World War II Order Of Battle, 160.

49 87th Division, “347th Infantry Regiment,” 88-89; "87th Infantry Division," Sons of Liberty Museum.

50 Stanton, World War II Order Of Battle, 160.

51 87th Division, “347th Infantry Regiment,” 94, 161; “Whidden Body Enroute Home from Europe,” Bradenton Herald, 2; Florida Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide (St. Augustine, FL: State Arsenal, St. Francis Barracks, 1980), 205.

52 “87th Infantry Division - Golden Acorn,” US Army Divisions.

53 Thomas Safford, “The Mass Surrender of German Troops to the 347th Infantry Regiment on May 6, 1945,” 87th Infantry Division Legacy Association, accessed June 17, 2024, https://87thinfantrydivision.com/wp-content/uploads/2004/08/MassSurrender.pdf.

54 “Eleven Floridians Killed in Action,” Bradenton Herald, May 21, 1945, https://www.newspapers.com/image/682816558.

55 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” entry for Charles H. Whidden

56 “Five things you may not know about Netherlands American Cemetery,” American Battle Monuments Commission, December 18, 2023, accessed July 1, 2024, https://www.abmc.gov/news-events/news/five-things-you-may-not-know-about-netherlands-american-cemetery; Netherlands American Cemetery and Memorial (Margarten, NL: American Battle Monuments Commission, 1960), 4.

57 “Netherlands American Cemetery,” American Battle Monuments Commission, accessed July 1, 2024, https://www.abmc.gov/Netherlands.

58 “America’s World War II Burial Program,” National Cemetery Administration, June 2020, accessed June 28, 2024, https://www.cem.va.gov/docs/wcag/history/WWII-Burial-Program-America.pdf.

59 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” Ancestry, Charles H. Whidden.

60 “Whidden Body Enroute Home from Europe,” Bradenton Herald, 2.

61 “Whidden Rites to Be Held at St. Augustine,”Bradenton Herald, April 19, 1949, 2; “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” Ancestry, Charles H. Whidden.

62 “Jewish Americans in World War II,” The National World War II Museum, accessed June 28, 2024, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/topics/jewish-americans-world-war-ii.

63 Mark Hilton, “87th Infantry Division Monument 'Golden Acorn',” The Historical Marker Database, February 13, 2018, accessed January 29, 2024, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=114067; “About Us,” 87th Infantry Division Legacy Association, accessed June 28, 2024, https://87thinfantrydivision.com/about-us.

64 “1950 United States Federal Census,”entry for Ronnie H Whidden.

65 “Returns to States,” Bradenton Herald, February 21, 1952, 2A.

66 “Aboard Destroyer,” Bradenton Herald, February 14, 1960, 5B.

67 “Viet River War Rages,” Fort Myers News-Press, January 16, 1969, 5C.

68 “Jeremiah Whidden Obituary,” Panama City News Herald, March 18, 2014, https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/newsherald/name/jeremiah-whidden-obituary?id=6610385; “Jeremiah ‘Pete’ Whidden,” FindAGrave, March 26, 2014, accessed July 1, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/126942992/jeremiah_whidden.

© 2024, University of Central Florida