Ninety-Third Infantry Division

By Marie Oury

The Ninety-third Infantry Division was one of two predominantly black divisions in the US Army during World War I. A higher percentage of African Americans served in the US Army during World War I than one would expect given the percentage of African Americans in the population. African Americans represented thirteen percent of the US Army while they were ten percent of the American civilian population.1 The number of black divisions had nothing to do with African Americans’ willingness to serve; instead, it was about racism. The Army placed seventy-five percent of the four hundred thousand African Americans who served in Quartermaster and Engineer units supervised by the Service of Supply and created only two African American combat divisions: the Ninety-second and the Ninety-third.2 About 40,000 soldiers staffed these two divisions, with some commissioned African American officers. Once in France, some of those officers, particularly those of higher rank, were deemed incompetent by their white officers because of racism and they were gradually replaced by white officers. 3

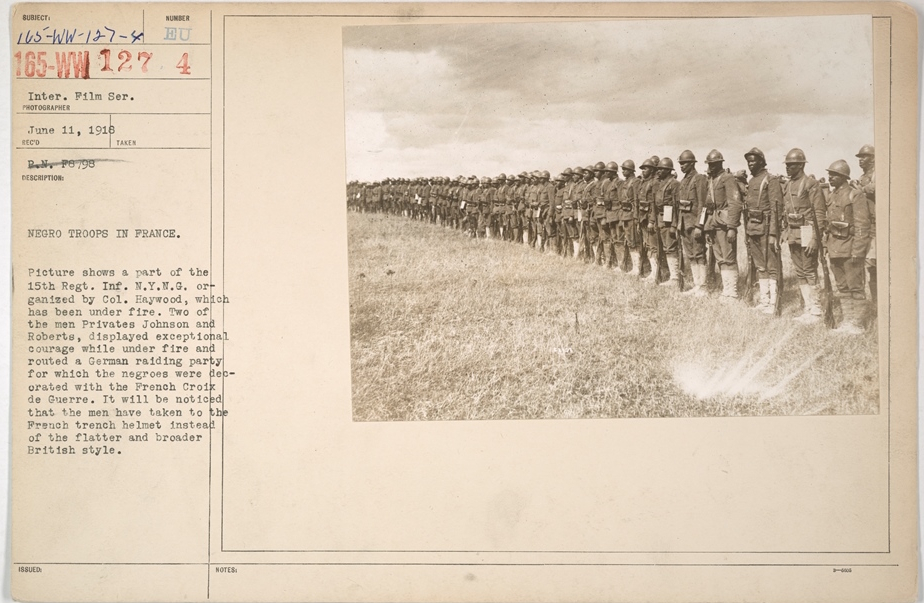

The Ninety-third division formed from four black Infantry Regiments: the 369th formerly the 15th Infantry Regiment, New York National Guard, the 370th formerly the 8th Infantry Regiment, Illinois National Guard, the 372nd, organized from small National Guard units from various part of the country, and the 371st composed only of draftees. 4 The Ninety-third Division never received all of the units it needed to support these regiments, it lacked an artillery component, and remained a provisional Division. As a result, it did not train or travel across the ocean as a division. The 369th Regiment was the first to arrive in France, in December 1917 and served for several months as labor unit. 5 It even lost its band. Led by Lieutenant James Reese Europe it toured and introduced ragtime and jazz to France. 6 When the rest of the division arrived in spring 1918, General Pershing faced two dilemmas. He did not know what to do with African American divisions; he was facing pressure from the French who demanded American regiments to help push back the German spring offensive. General Pershing solved both problems, he gave the Ninety-third Division to the French Army.

The French Army included Senegalese, Moroccan, and other black French Colonial Troops and was eager to get more men, regardless of their color. The four Regiments were quickly integrated into three different French Divisions, equipped and armed with French gears even wearing the French “Adrian” helmet.7

The performances of the four Regiments of the Ninety-third Division under the French command were impressive. The 369th Regiment, nicknamed the “Harlem Hellfighters,” stayed 191 days at the front, the longest of any American regiment. It was awarded with a regimental Croix de Guerre, a French Award for valor, for taking the town of Sechault, as well as with 170 individual Croix de Guerre from the French. The 371st Regiment, the second most decorated regiment in the division, and the 372nd were also awarded by the French with a regimental Croix de Guerre for their bravery under fire.8 Only the 370th was not awarded a regimental Croix de Guerre, although seventy-one soldiers received it as individuals and another twenty-one were awarded with the US Distinguished Service Cross.9 Two Members of the Ninety-third, Corporal Freddie Stowers and Private Henry Johnson, were awarded the Medal of Honor--the nation’s highest decoration for heroism.

When the 369th came home to Europe, they received a heroes welcome, marching in a victory parade in the streets of New York City.

Further Information

Barbeau, Arthur E. and Florette Henri. The Unknown Soldiers: African American Troops in World War I. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press, 1974.

Dalessandro, Robert J. and Gerald Torrence. Willing Patriots: Men of Color in the First World War. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2009.

Keene, Jennifer D. World War I: The American Soldier Experience. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2011.

Lengel, Edward G. To Conquer Hell: Meuse-Argonne, 1918 The Epic Battle That Ended the First World War. New York, New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 2008.

Lentz-Smith, Adriane. Freedom Struggles: African Americans and World War I. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Rubi, Richard. The Last of the Doughboys: The Forgotten Generation and their Forgotten World War. New York, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2013.

Williams, Chad. Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

1 Jennifer D. Keene, World War I: The American Soldier Experience (Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2006), 93.

2 Edward G. Lengel, To Conquer Hell: Meuse-Argonne, 1918 The Epic Battle That Ended the First World War (New York, New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 2008), 36.

3 Keene, World War I, 97.

4 Arthur E. Barbeau and Florette Henri. The Unknown Soldiers: African American Troops in World War I (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press, 1974), 111-136

5 Richard Rubi, The Last of the Doughboys: The Forgotten Generation and their Forgotten World War (New York, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2013), 266-269.

6 Barbeau and Henri. The Unknown Soldiers, 116.

7 Rubi, The Last of the Doughboys, 268.

8 Keene, World War I, 104.

9 Barbeau and Henri. The Unknown Soldiers, 127.

© 2018, University of Central Florida