Michael Angel Freije, Sr. (July 22, 1913-December 2, 1944)

Company L, 101st Infantry Regiment, 26th Infantry Division

By Amanda M. Sykes and Jim Stoddard

Early Life

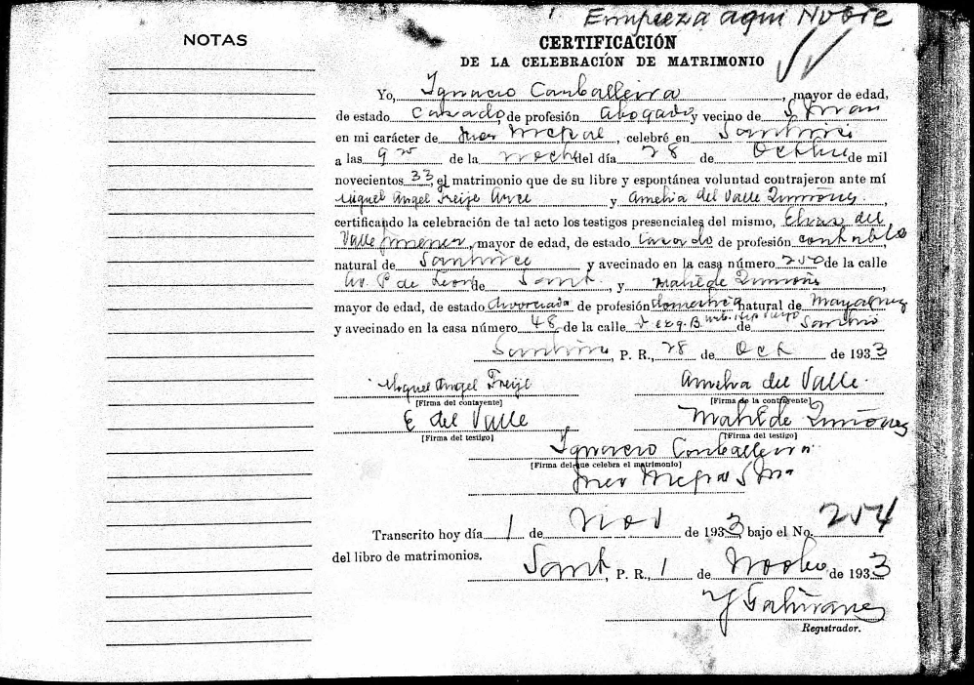

Michael Angel Freije was born Miguel Angel Freije in the Santurce district of San Juan, Puerto Rico on July 22, 1913.1 Santurce, located in the northern part of San Juan, experienced significant population and economic growth throughout the early twentieth century, in large part due to the American presence there.2 Miguel, who spent his childhood and early adult years in Puerto Rico, grew up within this context. In March 1917, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Jones Act into law, which extended US citizenship to Puerto Ricans like Miguel, who was three years old at the time.3 On October 28, 1933, Miguel married Amelia Del Valle, as seen on their marriage certificate.4 By 1935, the couple lived in Santurce with Amelia’s family, along with their young son Miguel Angel Frieje, Jr., born around 1934.5 The couple also had a daughter, Nilda, in 1937.6 Miguel sailed between San Juan and New York City at least twice during this time, in 1933 and 1937. He likely did not return to Puerto Rico after his arrival in New York City on March 5, 1937.7 Sometime before 1940, Miguel and Amelia divorced.8 Between his arrival in New York in 1937 and when he registered for the draft in 1940, Miguel settled in Jacksonville, FL.9

In October 1940, over sixteen million American men between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-five registered for the nation’s first peacetime draft. On October 16, Miguel registered for the draft in Jacksonville, FL under the name Michael Angel Freije.10 Despite the citizenship status granted to Puerto Ricans in 1917, many adopted new, anglicized names after moving to the continental US.11 Reasons for doing so included the desire to blend in with the majority White population and to avoid insinuations about being an outsider based on racial or ethnic discrimination.12 Miguel’s name change to Michael, then, proves understandable.13 Though he registered for the draft in 1940, the US military did not immediately select Michael for service. Throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s, he attended at least three years of college and worked as a skilled pattern and model maker.14 On June 30, 1942, he married Helen Spears in Jacksonville, FL.15

Military Service

The Army called Michael A. Freije to service on March 28, 1944. He enlisted at Fort McPherson, near Atlanta, GA.16 The US Army established the fort after the Civil War and named it for Major General James B. McPherson, the highest ranking Union soldier to die in the war. During World War II, the Army expanded the fort to train and deploy thousands of new soldiers. On July 11, 1944, it declared Fort McPherson one of nineteen Army Personnel Centers.17 After his initial training, Michael joined Company L, 101st Infantry Regiment of the 26th Infantry Division (ID).18

Prior to World War II, the 26th ID belonged to the Massachusetts National Guard. As the US prepared for the likelihood of entering the war, the government inducted the 26th ID into federal service on January 16, 1941. Shortly thereafter, the 26th ID began a heavy training cycle as it regularly moved to military bases throughout the US. On August 20, 1944, the 26th ID arrived in New York, where it prepared for deployment to the European Theater. Seven days later, Michael and the rest of the 26th ID deployed to France.19

The 26th ID arrived at Cherbourg, France on September 7, 1944. After traveling roughly 480 miles eastward over the next month, it relieved the 4th Armored Division and took up defensive positions in Salonnes-Montcourt, eighteen miles east of Nancy, the nearest city in eastern France. On November 8, the 26th ID sent three of its regiments, including Michaels’s 101st Infantry, to seize Vic-sur-Seille, a town in the Lorraine region about twenty miles east of Nancy, from the German Army. From there, the division advanced further east. On November 19, after they had traveled about twenty miles, strong German resistance and environmental factors, including flooding, halted the 26th ID’s assault at the Dieuze-Bénestroff line.20 The next day, the 4th Armored Division arrived to assist Michael and his comrades. Together they forced the German Army to withdraw further east. As the German Army retreated, however, it continued to harass the 26th ID’s eastward momentum. On November 21, Germans again halted the 26th ID, including Michael’s 101st Infantry Regiment, this time at the crossroad town of Albestroff, located about ten miles north of Dieuze. Michael and his fellow soldiers continued to fight there for two days, until the 328th Infantry Regiment finally arrived in support. Despite the German attacks and slow movement east, the efforts of the 4th Armored Division and the 26th ID made it possible for the 101st and the 328th Infantry Regiments to capture Albestroff on November 23.21

The 26th ID continued to fight its way toward the Sarre River in hopes of gaining control of the nearby town of Sarre-Union, roughly fifteen miles east of Albestroff.22 Once the division reached the Sarre River, it began crossing operations. On December 1, 1944, 26th ID coordinated with the 4th Armored Division to take control of Sarre-Union, allowing Michael’s 101st Infantry to continue moving east. The infantrymen fought house-to-house, sustaining high casualties due to repeated German counterattacks.23 Sadly, Michel made the ultimate sacrifice during this fighting. In early December, fragments from an artillery shell struck and injured Michael in his chest. Though he received medical attention at a nearby Army hospital, Michael Angel Freije succumbed to his wounds on December 2, 1944.24 Along with the 104th Infantry Regiment, the 101st secured Sarre-Union on December 4, 1944.25

Legacy

After Sarre-Union, the 26th ID continued to move east into the Alsace region. On December 7, five days after Michael’s death, the 26th ID regrouped at the Maginot Line, a series of fortifications and barriers that run along the eastern border of France.26 By this time, extreme weather conditions began to affect the soldiers of the 26th ID. A surviving member of the unit, Bill Stahl, later described the experience this way: “It was cold and snowy, and we had trench foot and trench foot took as many casualties as gunfire.” Stahl also expressed that they went months without showers or a change of socks.27 By mid-December, the 26th ID had traveled northwest to Metz, France, where the division focused on training replacements. On December 16, 1944, the Germans launched the Ardennes Offensive, also known in the US as the Battle of the Bulge.28 Four days later, on December 20, the 26th ID moved north into Luxembourg to support Allied fighting during this battle. As the unit moved north across Luxembourg through late December and January, they encountered heavy fighting and more extreme weather conditions. On January 25, 1945, the 101st Infantry Regiment of the 26th ID, which Michael Freije had served in, took the town of Clerf, in northern Luxembourg, helping to bring an Allied victory in the Battle of the Bulge.29

Throughout the Winter and Spring of 1945, the 26th ID fought east across Germany and crossed the Austrian border on May 1.30 On May 5, the division liberated Gusen, a sub-camp of the larger Mauthausen Concentration Camp in northern Austria.31 The Germans forced the prisoners of Gusen to mine stone quarries in the nearby mountains.32 As the 26th ID approached the camp, Nazi officials planned to collapse the mining tunnels with the prisoners inside. Fortunately, the division arrived before they carried out their plan. Since 1985, the US Holocaust Memorial Museum and the US Army’s Center of Military History have jointly honored thirty-six US Army divisions for their roles in the liberations of Nazi Concentration Camps. In 2002, these two organizations officially added the 26th ID to this list in recognition for the division’s part in the liberation of Gusen.33

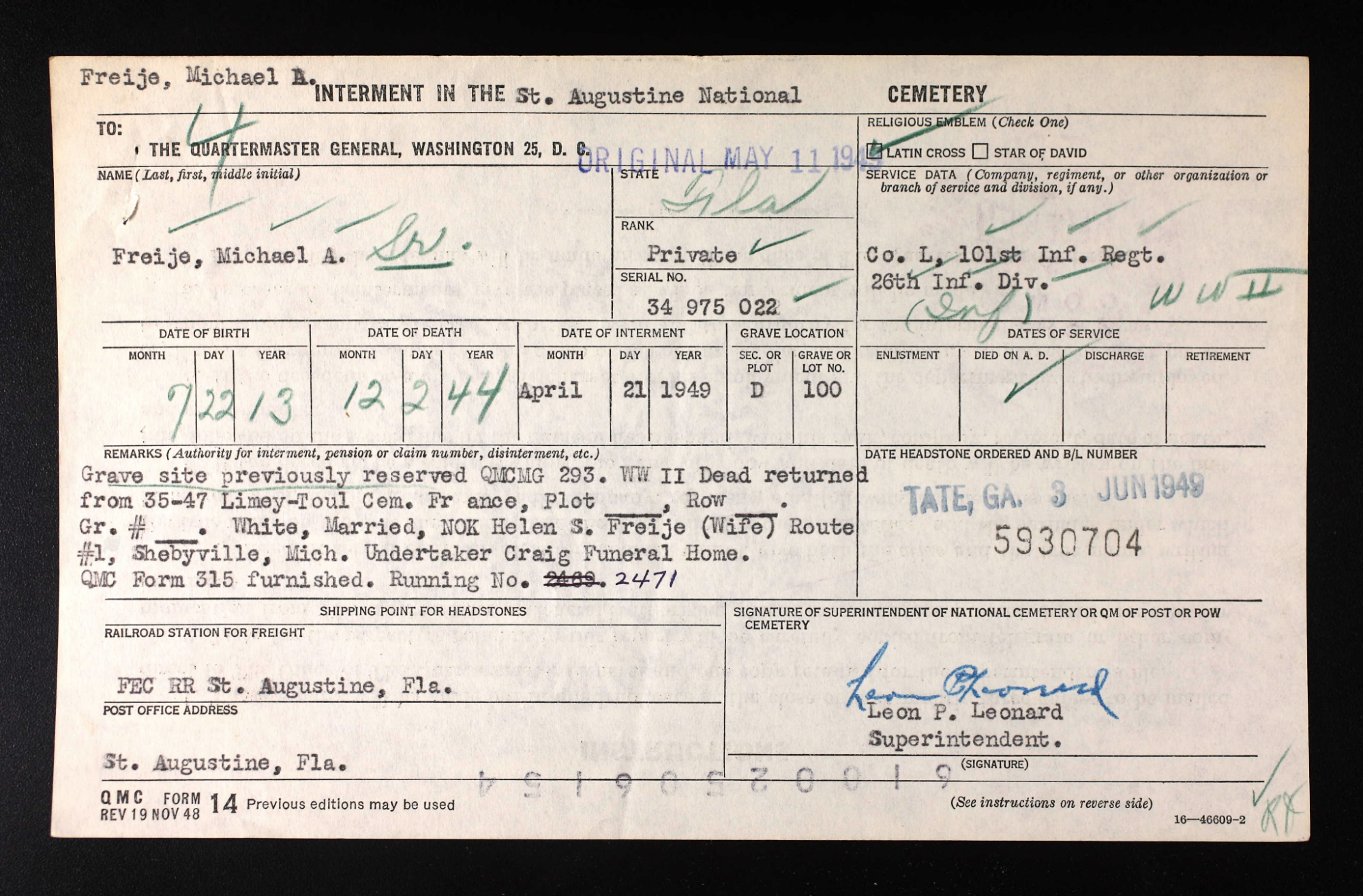

In February 1945, the Bradenton Herald and the Tampa Tribune announced Michael Freije’s death.34 Initially, the Army interred his remains in the Limey-Toul Cemetery in eastern France, located about eighty miles from where he died.35 Following World War I, the US War Department allowed the families of the nearly 120,000 US Veterans who died overseas during that conflict to decide on the repatriation of their loved ones’ remains. The US government consulted with fallen service members' next-of-kins to determine if their remains would stay overseas or return home. Approximately sixty-five percent of families decided on repatriation after World War I.36 In May 1946, Congress reapproved this initiative, known as the Return of the Dead Program.37 Through this program, the War Department returned over 170,000 Veterans who died during World War II to the US.38 As seen on his Interment Card, Michael’s widow, Helen, decided to bring her husband’s remains home. Michael Angel Freije now rests among his fellow Veterans in the St. Augustine National Cemetery in Section D, Plot 100.39

Michael Angel Freije was one of more than 60,000 Puerto Ricans who served proudly in World War II.40 Many who lived on the island joined the Army’s 65th Infantry Regiment, which originated in Puerto Rico.41 Nicknamed the “Borinqueneers,” a variation of a native Taino word meaning “Land of the Valiant Lord,” the 65th served in the Panama Canal zone and in the European theater, arriving in North Africa in early 1944 before joining the Allied fight in France and Germany. Whether they served in the Boriqueneers or in integrated units, Puerto Rican Americans like Freije played key roles in the war effort.42

Endnotes

1 Some dispute exists among historical records regarding Freije’s date of birth. His Draft Registration Card lists his date of birth as September 23, 1916. His Enlistment Record also lists 1916 as his birth year. His Interment Control Form has his birth date as July 22, 1913. Since the Interment Control Form informs the date on Freije’s headstone, this biography uses July 22, 1913 as his official date of birth; “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed September 11, 2023), entry for Michael Angel Freije; “World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938 - 1946,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed June 12, 2023), index record for Michael A Freije Sr.; “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed September 11, 2023), entry for Michael A Freije.

2 Ramon S. Corrada Del Rio, “The Historical-Geographical Development of Santurce, 1582-1930,” PhD Diss., (Johns Hopkins University, 1995), ProQuest (9523804), https://www.proquest.com/docview/304187588?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true, 18.

3 “Puerto Rico at the Dawn of the Modern Age: Nineteenth- and Early-Twentieth-Century Perspectives,” Library of Congress, accessed June 12, 2023, https://www.loc.gov/collections/puerto-rico-books-and-pamphlets/articles-and-essays/nineteenth-century-puerto-rico/puerto-rico-and-united-states/.

4 “Puerto Rico, Civil Registrations, 1885-2001,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed September 20, 2023), entry for Miguel Angel Freije Arce.

5 “Puerto Rico, U.S., Social and Population Schedules, 1935-1936,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed September 20, 2023), entry for Miguel Angel Freije, Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

6 “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed September 20, 2023), entry for Nilda Freije Y Del Valle, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

7 “Puerto Rico, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1901-1962,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed September 20, 2023), entry for Miguel A Freije; “U.S., Departing Passenger and Crew Lists, 1914-1966,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed September 20, 2023), entry for Miguel A Freije.

8 Amelia reported herself as divorced on the 1940 US Census, and neither Miguel, Jr. nor Nilda appear on this census with their mother; “1940 United States Federal Census,” database, Ancestry (ancestry.com: accessed September 20, 2023), entry for Amelia Del Valle Y Quiñones, San Juan, Puerto Rico.

9 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” Michael Angel Freije.

10 “U.S., World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947,” Michael Angel Freije.

11 “Puerto Rico at the Dawn of the Modern Age.”

12 Sam Roberts, “New Life in the US No Longer Means New Name,” New York Times, August 25, 2010, accessed June 12, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/26/nyregion/26names.html.

13 While we have found no records which explicitly denote Miguel’s name change, multiple sources that include identifying information help to corroborate this change.

14 “World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938 - 1946,” Michael A. Freije, Sr.

15 “Florida Marriages, 1830 - 1993,” database, FamilySearch (familysearch.com: accessed June 12, 2023), entry for Michael Angel Freije, Duval County.

16 “World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938 - 1946,” Michael A. Freije, Sr.

17 “Fort McPherson, Georgia,” The Army Historical Foundation, January 28, 2015, accessed September 20, 2023, https://armyhistory.org/fort-mcpherson-georgia/.

18 Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide: Preliminary Abridged Edition (St. Augustine, FL: St. Francis Barracks Special Archives, 1989), 206.

19 Shelby Stanton, Order of Battle U. S. Army, World War II (Novato: Presidio Press, 1984), 101.

20 Stanton, Order of Battle U. S. Army, World War II, 102.

21 Stanton, Order of Battle U. S. Army, World War II, 102.

22 Stanton, Order of Battle U. S. Army, World War II, 102.

23 The History of the 26th Yankee Division 1917 - 1919, 1941 - 1945, database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed June 12, 2023), 53-55.

24 “US, WWII Hospital Admission Card Files, 1942-1954,” database, Fold3 (fold3.com: accessed September 11, 2023), Michael A Freije; “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” Michael A Freije.

25 Stanton, Order of Battle U. S. Army, World War II, 102.

26 Stanton, Order of Battle U. S. Army, World War II, 102.

27 Chris Rogers, “WWII Vet’s Tale of Survival,” Winona Post, September 16, 2020, accessed October 2, 2023, https://www.winonapost.com/news/wwii-vet-s-tale-of-survival/article_d9ae78bc-e97e-5d64-9af9-b7ad38407a6a.html.

28 Stanton, Order of Battle U. S. Army, World War II, 102.

29 Stanton, Order of Battle U. S. Army, World War II, 102.

30 Stanton, Order of Battle U. S. Army, World War II, 102.

31 “The 26th Infantry Division during World War II,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed September 11, 2023, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-26th-infantry-division.

32 “Gusen,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed September 11, 2023, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/gusen.

33 “The 26th Infantry Division during World War II.”

34 “Florida Service Casualties Are Listed By Army,” The Bradenton Herald, February 14, 1945, 8; “Army Killed European Area,” The Tampa Tribune, February 15, 1945, 6.

35 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” Michael A. Freije.

36 “America’s World War II Burial Program,” US Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration, accessed October 13, 2023, https://www.cem.va.gov/publications/NCA_America_WWII_Burial_Program.pdf, 4-5.

37 Kim Clarke, “Gruesome but Honorable Work: The Return of the Dead Program Following World War II,” Perspectives on History, May 24, 2021, accessed October 2, 2023, https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/may-2021/gruesome-but-honorable-work-the-return-of-the-dead-program-following-world-war-ii.

38 “America’s World War II Burial Program,” https://www.cem.va.gov/publications/NCA_America_WWII_Burial_Program.pdf, 10.

39 “U.S., National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962,” Michael A Freije; Department of Military Affairs, St. Augustine National Cemetery Index and Biographical Guide, 206.

40 McKenna Britton, “1940-45: 72,000 Puerto Ricans Serve During WWII,” Neighbors Vecinos, accessed October 24, 2023, https://omeka.hsp.org/s/puertoricanphillyexperience/page/puertoricansinww2#:~:text=It%20is%20no%20surprise%2C%20then,in%20the%20Second%20World%20War.

41 Shannon Collins, “Puerto Ricans Represented Throughout U.S. Military History,” U.S. Department of Defense, accessed October 24, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/974518/puerto-ricans-represented-throughout-us-military-history/.

42 Harry Franqui-Rivera, “The Puerto Rican Experience in The U.S. Military: A Century of Unheralded Service,” Center For Puerto Rican Studies, accessed October 24, 2023, https://centropr-archive.hunter.cuny.edu/digital-humanities/pr-military/world-war-ii .

© 2023, University of Central Florida